http://www.politico.com/story/2017/07/06/health-care-premiums-republicans-obamacare-240242

Republicans promise to bring down the cost of health insurance for millions of Americans by repealing Obamacare.

But in the race to make insurance premiums cheaper, they ignore a more ominous number — the $3.2 trillion-plus the U.S. spends annually on health care overall.

Republicans are betting it’s smart politics to zoom in on the pocketbook issues affecting individual consumers and families. But by ignoring the mounting expenses of prescription drugs, doctor visits and hospital stays, they allow the health care system to continue on its dangerous upward trajectory.

That means that even if they fulfill their seven-year vow to repeal Obamacare and rein in premiums for some people,the nation’s mounting costs are almost sure to pop out in other places — includingfresh efforts by insurers and employers to push more expenses onto consumers through bigger out-of-pocket costs and narrower benefits.

As a presidential candidate, Donald Trump didn’t talk much about health care in 2016 — not compared to the border wall, jobs, or Hillary Clinton’s emails. But the final days of the campaign coincided with the start of the Obamacare sign-up season — and Trump leapt to attack what he called “60, 70, 80, 90 percent” premium increases. Big spikes did occur in some places, but they weren’t the rule, and most Obamacare customers got subsidies to defray the cost.

But the skyrocketing premium made a good closing message for Trump — and Republicans have stuck with it.

“The Republicans decoded: What is the single, 10-second thing that says why you are running against the Affordable Care Act?” said Bob Blendon, an expert on health politics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “Premiums became the face of what’s wrong.”

The GOP approach differs from the tack Democrats took when they pushed for the Affordable Care Act back in 2009-10. That debate was about covering more Americans — and about “bending the curve” of national health care spending, which eats up an unhealthy portion of the economy.

Conservatives like Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas argue that Obamacare failed to achieve its promise to bring down costs.

“The biggest reason that millions of people are unhappy with Obamacare is it’s made premiums skyrocket,” said Cruz, who is leading a small band of conservatives trying to pull the Senate repeal bill to the right as leaders seek to cobble together 50 votes. “We’ve got to fix that problem that was created by the failing policies of Obamacare.”

The answer, he says, is getting government out of the way. Conservatives want to free insurers from many of the coverage requirements and consumer protections in Obamacare. That means they could sell plans that wouldn’t cover as comprehensive a set of benefits — but they’d be cheaper.

Even some prominent critics of the Affordable Care Act think that’s not getting at the heart of the U.S. health care problem, even if it sounds good to voters.

“Too many in the GOP confuse adjustments in how insurance premiums are regulated with bringing competitive pressures to bear on the costs of medical services,” the American Enterprise Institute’s James Capretta wrote in a recent commentary for Real Clear Health. “They say they want lower premiums for consumers, but their supposed solution would simply shift premium payments from one set of consumers to another.”

The Congressional Budget Office has not yet evaluated how the House repeal bill, which narrowly passed, or the Senate companion legislation, which is still being negotiated, would affect overall health spending in coming years. It is already a sixth of the U.S. economy — more than 17 cents out of every dollar — and spending is still growing, partly because of an aging population.

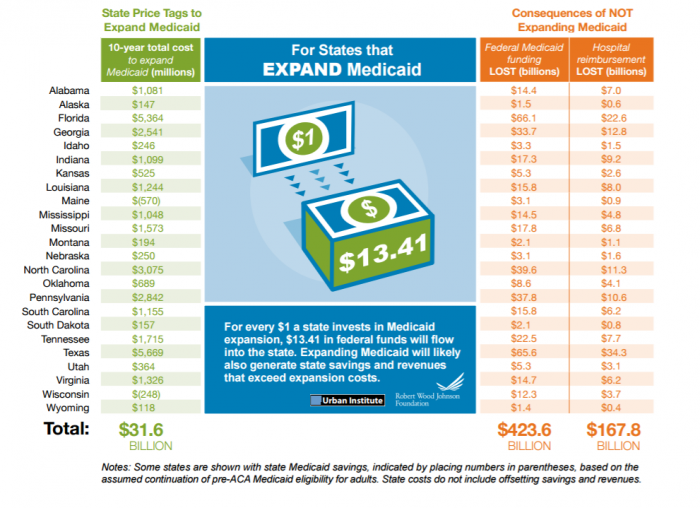

The nonpartisan budget office projected the federal government would spend about $800 billion less on Medicaid over a decade, as the GOP legislation upends how Washington traditionally paid its share. But CBO hasn’t yet reported on how that would affect the health sector overall.

Many Republicans predict that limiting federal payments to states would force Medicaid to be more efficient. Democrats says the GOP bill would basically thrust those costs onto the states and onto Medicaid beneficiaries themselves, who are too poor, by definition, to get their care — often including nursing homes — without government assistance.

The CBO gave a mixed assessment of what would happen to premiums under the GOP proposals. They’d rise before they’d fall — and they wouldn’t fall for everyone. Older and sicker people could well end up paying more, and government subsidies would be smaller, meaning that even if the sticker price of insurance comes down, many people at the lower end of the income scale wouldn’t be able to afford it.

“Despite being eligible for premium tax credits, few low-income people would purchase any plan,” the CBO said.

Shrinking insurance benefits may work out fine for someone who never gets injured or sick. But there are no guarantees of perpetual good health; that’s why insurance exists. If someone needs medical treatment not covered in their slimmed-down health plan, the costs could be astronomical and the treatment unobtainable.

Couple that with skimpier benefits, bigger deductibles, smaller subsidies and weaker patient protections, and “Trumpcare” — or whatever an Obamacare successor ends up being called — could spell voter backlash in the not-too-distant future, particularly as poll after poll shows the legislation is already deeply unpopular.

“Premiums are one of the important ways in which consumers experience cost. But it’s not the only way,” said David Blumenthal, president of the Commonwealth Fund, a liberal-leaning think tank, and a former Obama administration official. But deductibles running into the thousands of dollars and steep out-of-pocket costs, he added, “are a source of discontent for Trump and non-Trump voters alike.”

Even the 2009 health debate early in the Obama presidency, which looked at staggering national health spending and what it meant for the U.S. economy, didn’t translate into a bottom line for many American families, said Drew Altman, president and CEO of the Kaiser Family Foundation, which has extensively polled public attitudes on health care.

And the bottom line — the cost of care — is what ordinary people focus on, Kaiser has found. Not just on premiums, but on what it costs to see a doctor, to fill a prescription, or to get treated for a serious disease.

“That’s what all of our polling shows,” Altman said. “The big concern is health care costs.”

Democrats have a long list of things they detest about the Republican repeal-and-replace legislation — and the lack of attention to overall health spending for the country and for individuals and families is right up there.

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), the top Democrat on the Finance Committee, would like a bill that tackles cost — starting with rising drug prices. But this bill, he said, does nothing about health care costs.

“This really isn’t a health bill. This is a tax-cut bill,” he said. The repeal bills would kill hundreds of billions of dollars of taxes — many on the health care industry or wealthy people — that were included in Obamacare to finance coverage expansion, though the Senate is now considering keeping some of them to provide more generous subsidies.

Conservative policy experts acknowledge that premiums aren’t the whole story.

The overall cost and spending trajectory “is something we have to get to,” said Stanford University’s Lanhee Chen, who has advised Mitt Romney and other top Republicans. But for now, he said, premiums are a good first step.