Administrative waste, denials, and deadly incentives — the U.S. model shows what happens when profit rules.

The United States is the only country where a health insurance executive has been gunned down in the street. But that’s not the only thing that’s unique about American health insurance.

Almost all of our peer countries – advanced, free-market democracies — have health insurance companies. In some cases (Germany, Switzerland, Japan), private health insurance is the chief way to pay for medical care. In others (such as Great Britain), private insurance works as a supplement to government-run health care systems. But there’s a fundamental difference between health insurance elsewhere and the U.S. system.

In all the other advanced democracies, basic health insurance is not for profit; the insurers are essentially charities. They exist not to pay large sums to executives and investors, but rather to keep the population healthy by assuring that everyone can get medical care when it’s needed.

America’s health insurance giants are profit-making businesses. Indeed, in the insurers’ quarterly earnings reports to investors, the standard industry term for any sums spent paying people’s medical bills is “medical loss.” They view paying your doctor bill as a loss that subtracts from the dividends they owe their stockholders.

When I studied health care systems around the world, I asked economists and doctors and health ministers why they want health insurance to be a nonprofit endeavor. Everyone gave essentially the same answer:

There’s a fundamental contradiction between insuring a nation’s health and making a profit on health insurance.

Health insurance exists to help people get the preventive care and treatment they need by paying their medical bills. But the way to make a profit on health insurance is to avoid paying medical bills. Accordingly, the U.S. insurance giants have devised ingenious methods for evading payment — schemes like high deductibles, narrow networks of approved doctors, limited lists of permitted drugs, and pre-authorization requirements, so that the insurance adjuster, not your doctor, determines what treatment you get.

Other countries don’t allow those gimmicks. In America, the patient pays twice — first the insurance premium, and then the bill that the insurer declines to pay. That’s why Americans hate health insurance companies — as reflected in the tasteless barrage of angry social media commentary aimed at the victim, not the perpetrator, of the sidewalk shooting in 2024 of UnitedHealthcare’s CEO Brian Thompson in New York City.

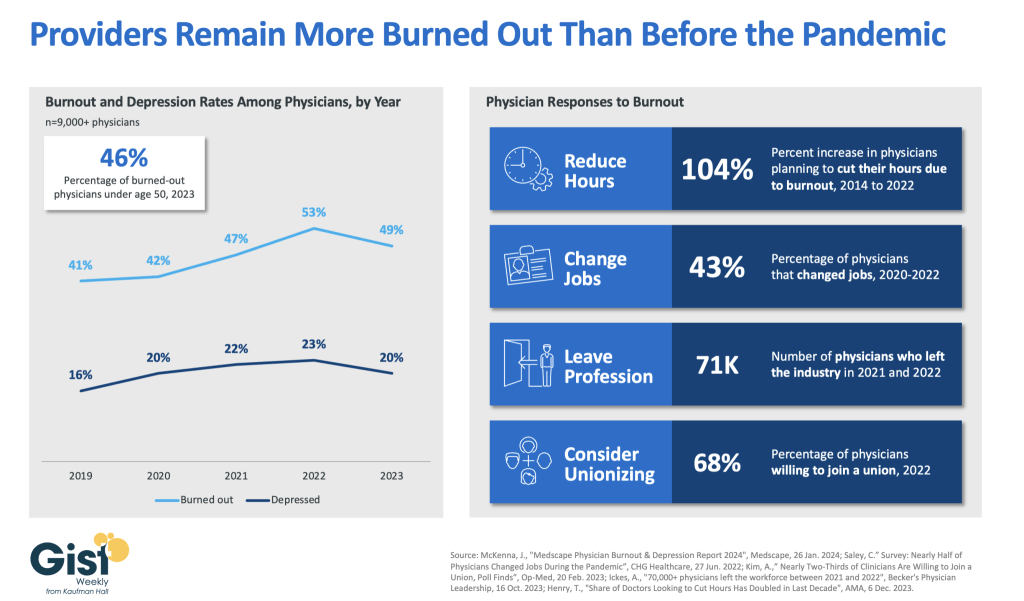

Another unique aspect of U.S.-style health insurance is the huge amount of money our big insurers waste on administrative costs. Any insurance plan has administrative expenses; you’ve got to collect the premiums, review the patients’ claims, and get the payments out to doctors and hospitals.

In other countries, the administrative costs are limited to about 5% of premium income; that is, insurers use 95% of all the money they take in to pay medical bills. But the U.S. insurance giants routinely report administrative costs in the range of 15% to 20%.

When the first drafts of the Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) were floated on Capitol Hill in 2009, the statutory language called for limiting insurers’ admin costs to 12% of premium income. Then the insurance lobby went to work. The final text of that law allows them to spend up to 20% of their income on salaries, marketing, dividends, and other stuff that doesn’t pay anybody’s hospital bill.

There is one American insurance system, however, that is as thrifty as foreign health insurance plans. Medicare, the federal government’s insurance program for seniors and the disabled, reports administrative costs in the range of 3% — about one-fifth as much as the big private insurers fritter away. And Medicare’s administrators — federal bureaucrats — are paid less than a tenth as much as the executives running the far less efficient private insurance firms.

Americans generally believe that the profit-driven private sector is more efficient and innovative than government. In many cases, that’s true. I wouldn’t want some government agency designing my cell phone or my hiking boots.

But when it comes to health insurance, all the evidence shows that nonprofit and government-run plans provide better coverage at lower cost than the private plans from America’s health insurance giants.

If we were to make basic health insurance a nonprofit endeavor, as it is everywhere else, or put everybody on a public plan like Medicare, the U.S. would save billions and improve our access to life-saving care. Then Americans might stop celebrating on social media when an insurance executive is killed.