Category Archives: Employee Termination

Tower Health fires physician accused of prescribing ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19

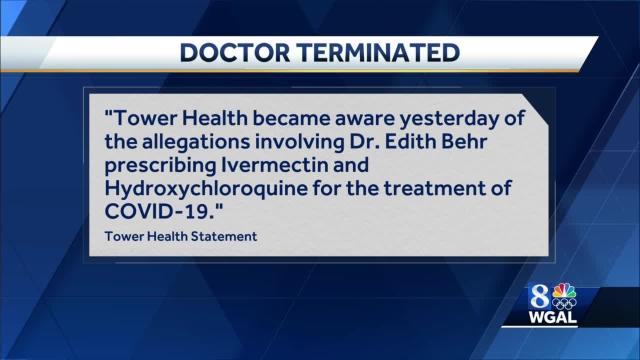

A Pennsylvania physician accused of prescribing ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine to treat and prevent COVID-19 has been terminated from Tower Health, PennLive reported Feb. 4.

Edith Behr, MD, is allegedly linked to Christine Mason, a woman who used a Facebook account to connect people to a physician for hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin prescriptions. A social media user claimed Dr. Behr was the source of the prescriptions and reported her to authorities and her employer, according to PennLive.

West Reading, Pa.-based Tower Health officials became aware of the allegations against Dr. Behr Feb. 2 and took immediate action.

“Tower Health became aware yesterday of the allegations involving Dr. Edith Behr prescribing ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19,” Tower Health said in a Feb. 3 statement to PennLive. “We investigated the matter and, as a result, Dr. Behr’s employment with Tower Health Medical Group has been terminated effective immediately.”

Dr. Behr was a surgeon at Phoenixville (Pa.) Hospital, which is owned by Tower Health, according to the report.

Ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine have not been approved by the FDA for prevention or treatment of COVID-19.

Cartoon – Keep Up the Good Work

CommonSpirit Health mandates COVID-19 vaccination for employees in 21 states

CommonSpirit Health is requiring full COVID-19 vaccination for its 150,000 employees, the Chicago-based health system said Aug. 12.

The requirement applies to employees at CommonSpirit’s 140 hospitals and more than 1,000 care sites and facilities in 21 states. It includes physicians, advanced practice providers, volunteers and others caring for patients at health system facilities.

“As healthcare providers, we have a responsibility to help end this pandemic and protect our patients, our colleagues and those in our communities — including the most vulnerable among us,” Lloyd H. Dean, CEO of CommonSpirit, said in a news release. “An abundance of evidence shows that the vaccines are safe and highly effective. Throughout the pandemic we have made data-driven decisions that will help us best fulfill our healing mission, and requiring vaccination is critical to maintaining a safe care environment.”

The compliance deadline for the vaccination requirement is Nov. 1, although the implementation date will vary by region in accordance with local and state regulations. Employees who are not in compliance and do not obtain a medical or religious exemption risk losing their jobs.

‘Shkreli Awards’ Shame Healthcare Profiteers

Lown Institute berates greedy pricing, ethical lapses, wallet biopsies, and avoidable shortages.

Greedy corporations, uncaring hospitals, individual miscreants, and a task force led by Jared Kushner were dinged Tuesday in the Lown Institute‘s annual Shkreli awards, a list of the top 10 worst offenders for 2020.

Named after Martin Shkreli, the entrepreneur who unapologetically raised the price of an anti-parasitic drug by a factor of 56 in 2015 (now serving a federal prison term for unrelated crimes), the list of shame calls out what Vikas Saini, the institute’s CEO, called “pandemic profiteers.” (Lown bills itself as “a nonpartisan think tank advocating bold ideas for a just and caring system for health.”)

Topping the list was the federal government itself and Jared Kushner, President’s Trump’s son-in-law, who led a personal protective equipment (PPE) procurement task force. The effort, called Project Airbridge, was to “airlift PPE from overseas and bring it to the U.S. quickly,” which it did.

“But rather than distribute the PPE to the states, FEMA gave these supplies to six private medical supply companies to sell to the highest bidder, creating a bidding war among the states,” Saini said. Though these supplies were supposed to go to designated pandemic hotspots, “no officials from the 10 hardest hit counties” said they received PPE from Project Airbridge. In fact, federal agencies outbid states or seized supplies that states had purchased, “making it much harder and more expensive” for states to get supplies, he said.

Number two on the institute’s list: vaccine maker Moderna, which received nearly $1 billion in federal funds to develop its mRNA COVID-19 preventive. It set a price of between $32 and $37 per dose, more than the U.S. agreed to pay for other COVID vaccines. “Although the U.S. has placed an order for $1.5 billion worth of doses at a discount, a price of $15 per dose, given the upfront investment by the U.S. government, we are essentially paying for the vaccine twice,” said Lown Institute Senior Vice President Shannon Brownlee.

Webcast panelist Don Berwick, MD, former acting administrator for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, noted that a lot of work went into producing the vaccine at an impressive pace, “and if there’s not an immune breakout, we’re going to be very grateful that this happened.” But, he added, “I mean, how much money is enough? Maybe there needs to be some real sense of discipline and public spirit here that goes way beyond what any of these companies are doing.”

In third place: four California hospital systems that refused to take COVID-19 patients or delayed transfers from hospitals that were out of beds. A Wall Street Journal investigation found that these refusals or delays were based on the patients’ ability to pay; many were on Medicaid or were uninsured.

“In the midst of such a pandemic, to continue that sort of behavior is mind boggling,” said Saini. “This is more than the proverbial wallet biopsy.”

The remaining seven offenders:

4. Poor nursing homes decisions, especially one by Soldiers’ Home for Veterans in western Massachusetts, that worsened an already terrible situation. At Soldiers’ Home, management decided to combine the COVID-19 unit with a dementia unit because they were low on staff, said Brownlee. That allowed the virus to spread rapidly, killing 76 residents and staff as of November. Roughly one-third of all COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. have been in long-term care facilities.

5. Pharmaceutical giants AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson, which refused to share intellectual property on COVID-19, instead deciding to “compete for their profits instead,” Saini said. The envisioned technology access pool would have made participants’ discoveries openly available “to more easily develop and distribute coronavirus treatments, vaccines, and diagnostics.”

Saini added that he was was most struck by such an attitude of “historical blindness or tone deafness” at a time when the pandemic is roiling every single country.

Berwick asked rhetorically, “What would it be like if we were a world in which a company like Pfizer or Moderna, or the next company that develops a really great breakthrough, says on behalf of the well-being of the human race, we will make this intellectual property available to anyone who wants it?”

6. Elizabeth Nabel, MD, CEO of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, because she defended high drug prices as a necessity for innovation in an op-ed, without disclosing that she sat on Moderna’s board. In that capacity, she received $487,500 in stock options and other payments in 2019. The value of those options quadrupled on the news of Moderna’s successful vaccine. She sold $8.5 million worth of stock last year, after its value nearly quadrupled. She resigned from Moderna’s board in July and, it was announced Tuesday, is leaving her CEO position to join a biotech company founded by her husband.

7. Hospitals that punished clinicians for “scaring the public,” suspending or firing them, because they “insisted on wearing N95 masks and other protective equipment in the hospital,” said Saini. Hospitals also fired or threatened to fire clinicians for speaking out on COVID-19 safety issues, such as the lack of PPE and long test turnaround times.

Webcast panelist Mona Hanna-Attisha, MD, the Flint, Michigan, pediatrician who exposed the city’s water contamination, said that healthcare workers “have really been abandoned in this administration” and that the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration “has pretty much fallen asleep at the wheel.” She added that workers in many industries such as meatpacking and poultry processing “have suffered tremendously from not having the protections or regulations in place to protect [them].”

8. Connecticut internist Steven Murphy, MD, who ran COVID-19 testing sites for several towns, but conducted allegedly unnecessary add-ons such as screening for 20 other respiratory pathogens. He also charged insurers $480 to provide results over the phone, leading to total bills of up to $2,000 per person.

“As far as I know, having an MD is not a license to steal, and this guy seemed to think that it was,” said Brownlee.

9. Those “pandemic profiteers” who hawked fake and potentially harmful COVID-19 cures. Among them: televangelist Jim Bakker sold “Silver Solution,” containing colloidal silver, and the “MyPillow Guy,” Mike Lindell, for his boostering for oleandrin.

“Colloidal silver has no known health benefits and can cause seizures and organ damage. Oleandrin is a biological extract from the oleander plant and known for its toxicity and ingesting it can be deadly,” said Saini.

Others named by the Lown Institute include Jennings Ryan Staley, MD — now under indictment — who ran the “Skinny Beach Med Spa” in San Diego which sold so-called COVID treatment packs containing hydroxychloroquine, antibiotics, Xanax, and Viagra, all for $4,000.

Berwick commented that such schemes indicate a crisis of confidence in science, adding that without facts and science to guide care, “patients get hurt, costs rise without any benefit, and confusion reigns, and COVID has made that worse right now.”

Brownlee mentioned the “huge play” that hydroxychloroquine received and the FDA’s recent record as examples of why confidence in science has eroded.

10. Two private equity-owned companies that provide physician staffing for hospitals, Team Health and Envision, that cut doctors’ pay during the first COVID-19 wave while simultaneously spending millions on political ads to protect surprise billing practices. And the same companies also received millions in COVID relief funds under the CARES Act.

Berwick said surprise billing by itself should receive a deputy Shkreli award, “as out-of-pocket costs to patients have risen dramatically and even worse during the COVID pandemic… and Congress has failed to act. It’s time to fix this one.”

Fired Nurse Faces Board Review for Wearing Hospital Scrubs

In late November, Cliff Willmeng’s wife handed him a sealed envelope at their Minneapolis home “with some trepidation,” he recalled. He looked at the sender printed on the front: “Minnesota Board of Nursing.” Willmeng, a registered nurse, opened the letter and read that the board was investigating his conduct as a nurse at United Hospital in St. Paul, from which he’d been fired in May. Clearly his license was at stake.

Willmeng was disappointed, but not surprised. He believes the review is due to his standing up for his own safety and that of other nurses, and for filing a lawsuit and union grievance against United’s parent company, Allina Health, after his termination.

He also thinks the investigation, like his firing, has been orchestrated to scare other healthcare workers away from reporting safety violations and concerns as the pandemic rages, and to make an example out of the former union steward.

The investigation is being led by a former Allina executive: “It feels meant to intimidate me,” he said.

Taking a Stand for Safety

Willmeng is a 13-year nursing veteran, husband, and father, who began working at United in October 2019.

When the pandemic hit late last winter, managers instructed nurses to use and reuse their own scrubs rather than hospital-issued scrubs. They were asked to launder their scrubs themselves at home.

Willmeng and others worried about bringing the virus home and pressed for the hospital scrubs. These scrubs were available, he said, and healthcare workers were permitted to wear hospital gear at Abbott Northwestern, another Allina hospital in Minneapolis.

In addition, while United managers told staff their laundering co-op could not keep up with demand for all the scrubs, the co-op denied that assertion, said Brittany Livaccari, RN, an ER nurse and union steward at United.

Willmeng addressed his concerns with management, filed state OSHA complaints, and enlisted the Minnesota Nurses Association (MNA). “He was taking action 100% to protect himself and to protect his patients,” Livaccari said.

But management did not change its policy, which was devised before the pandemic, and pointed to early-pandemic CDC and Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) guidelines — even when Willmeng shared emerging reports suggesting the policy was jeopardizing safety.

“It did feel like a pissing match,” Livaccari said. “We didn’t feel like we were being protected. … We weren’t being valued.”

Managers repeatedly wrote up Willmeng and colleagues who wore the hospital scrubs despite the policy. “It definitely felt like an intimidation tactic — ‘You’re going to do this, you’re going to follow these policies,'” Livaccari said. “A lot of staff chose to stop wearing those scrubs because they needed their job, they have families to pay for, they were afraid.”

Willmeng continued to wear the hospital scrubs. “I had to decide whether that policy was most important, or the safety of my workplace and public health and my family,” he said.

On May 8, the hospital terminated Willmeng. He said its stated cause was violating hospital policies regarding uniform code and a respectful workplace.

Two weeks later, the local nurses’ union held a rally that drew hundreds of supporters for Willmeng and blasted the hospital’s scrub policy.

‘I’m Not a Bad Nurse’

In June, Willmeng sued Allina for whistleblower retaliation and wrongful termination. The case is scheduled to be heard next August.

His union grievance is set to be arbitrated in January. He maintains his firing was not for “just cause” because United’s uniform code policy violated standard nursing practices.

Willmeng has been running the website WeDoTheWork, which describes itself as “worker-run journalism.” It’s an independent but union-affiliated publication that “unflinchingly tells our side of the story, and takes the fight to management.”

He’s been publicizing his case on that website. In his Twitter account he notes, “I believe in the working class, democratically run economy, socialism, and revolution.”

Willmeng is applying for jobs, but despite his experience, a national nursing shortage, and reports of severe understaffing as hospitalizations surge again, Willmeng has not even been interviewed by any of the roughly 20 medical centers he has applied to.

He thinks he is being blackballed. “I’m not a bad nurse,” he said.

The board letter cited these concerns: “On April 16, 2020, you received a written warning for not following the uniform policy,” reads one item, citing a report shared with the board. “On May 5, 2020, you were issued a final written warning for repeatedly violating policy. … On May 8, 2020, you were terminated from employment based on violating hospital policies, behavioral expectations, code of conduct, and not following the directions of your manager.” The letter asks Willmeng to respond to eight questions.

“This looks like it was taken right out of my HR file,” he said. The board will not reveal who reported him, citing confidentiality policies. But he is certain — given the detail in the letter — that it was Allina/United management.

The nursing board cannot comment on Willmeng’s review to protect confidentiality, said executive director Shirley Brekken, MS, RN. The board receives about 1,200 complaints annually and first determines whether a complaint would merit disciplinary action if true. If so, it launches a review.

Allina declined to answer questions via a spokesperson, citing the lawsuit. “We cannot appropriately retain employees who willfully and repeatedly choose to violate hospital policies,” according to an emailed statement. Throughout the pandemic Allina has been following CDC and MDH guidelines, “which do not consider hospital issued scrubs as PPE [personal protective equipment].”

“In the early days of the pandemic, our local and national supply chain was extremely stressed,” the statement continues. “Our practices are aligned with other local and national hospitals … and have enabled us to allocate the appropriate supplies for daily patient care and ongoing care for COVID-19 patients.”

But United healthcare workers still lack hospital scrubs and enough N95 masks, Livaccari said, and the hospital is severely understaffed as the patient load increases. “We hear, ‘It’s a pandemic. You have to do more with less,'” she said. “It’s a really bad situation.”

Retaliation and Intimidation

Some think Willmeng’s review was initiated primarily to retaliate against him, not to protect public health and safety.

“Hospitals, they want a docile workforce, they want a workforce they can control,” said John Kauchick, RN, a retired 37-year nursing veteran who advocates for workplace rights. They do so “by fear and intimidation,” he added. “A nurse’s number one fear is to be turned in to a board of nursing for anything.”

“If you’re a whistleblower and you speak truth to power, that will get you a disciplinary hearing even more so than if there is patient harm.”

The letter was drafted more than six months after Willmeng was fired, and after he filed the lawsuit and union grievance. Just before he received the letter, he was elected to the MNA board. The timing strikes Willmeng and Kauchick as significant.

“If you think there’s been a violation, you are supposed to report that in a much shorter time period,” Kauchick said. Kauchick thinks Allina filed the complaint as leverage, to persuade Willmeng to drop the grievance and lawsuit.

But Livaccari noted the process can take up to six months, and that every firing is supposed to be reported to the board.

Like Kauchick, she takes umbrage with the review’s leader: Stephanie Cook, MSN, RN, a board nursing practice specialist who spent 24 years as a director with Allina. She was a member of multiple Allina committees, including its ethics committee, according to reports. She was with Allina as recently as 2018. Brekken confirmed her employment with Allina, noting that it’s “a very large system.”

Regardless, that’s a conflict of interest, Kauchick and Livaccari said, arguing that Cook should not be part of the review. “It’s just so blatantly obvious. How are you going to look at this with an unbiased lens when you worked for the organization that says Cliff was in the wrong?” Livaccari said. “It’s so inappropriate.”

This is not uncommon, Kauchick said, noting state nursing board reviews are “really just designed to get rid of whistleblowers. It’s like a buddy system. They hire higher-ups from big hospital systems. It’s just incestuous.”

Brekken was aware of Cook’s background before a colleague assigned this review to Cook, she said, noting the board vets staff for personal involvement in cases. Brekken “might consider” removing Cook from the review given her connection to Allina, she said, but added: “Many individuals on our staff may have worked for a particular health system throughout their career.”

The board could throw out the complaint or take action. Such actions typically range from a reprimand to revoking a nurse’s license, Brekken said. A staff member and board member together will review the report and Willmeng’s response, but she said the board itself makes final decisions.

Willmeng is also focused on the grievance, which asks Allina to provide full back pay and reinstate him.

“I would not feel comfortable; I’d feel very anxious” going back, he said. “But I’m an ER nurse. I belong in the ER…. It’s important for a frontline healthcare worker to demonstrate that when they stand up and speak truthfully and assertively about working conditions and patient safety, that they can’t just be triangulated.”

His salary — about twice his current unemployment benefits — is also a draw, he acknowledged.

Meanwhile, he continues applying for other jobs. His life insurance cost doubled and his family switched to his wife’s lesser health insurance plan, he said. A fourth-grade teacher with a local public school system, her salary is the primary support for themselves and their two children.

Willmeng also just hired an attorney at $250 an hour to help him respond to the board letter. “It’s not something I take lightly,” he said. “There’s cause for real concern. That’s my nursing license, that’s everything.“

Indiana hospital employee fired after speaking to New York Times

NeuroBehavioral Hospital in Crown Point, Ind., terminated the employment of a discharge planner last week after she spoke to the New York Times about nursing homes discharging unprofitable patients, a practice known as “patient dumping,” the NYT reports.

In the Sept. 19 NYT article, Kimberly Jackson said that during the pandemic nursing homes in Illinois and Michigan have repeatedly sent elderly and disabled Medicaid patients to NeuroBehavioral Hospital, a psychiatric facility, even though they were not experiencing psychosis, seemingly in an effort to get rid of patients who are not lucrative for reimbursement or require extra care.

“The homes seem to be purposely taking symptoms of dementia as evidence of psychosis,” Ms. Jackson is quoted in the article.

She was fired from NeuroBehavioral Hospital Sept. 24. Rebecca Holloway, the hospital’s corporate director of human resources, told the NYT that Ms. Jackson violated the hospital’s media policy.

Ms. Jackson told the newspaper she was shocked to be fired for speaking to the media.

“I saw something that was wrong, and I called it out,” she said.

NeuroBehavioral Hospital is part of NeuroPsychiatric Hospitals. The South Bend, Ind.-based network has five facilities in Indiana, two in Texas and one in Arizona.