Since its opening in a converted wood-frame mansion 117 years ago, Greenwood Leflore Hospital had become a medical hub for this part of Mississippi’s fertile but impoverished Delta, with 208 beds, an intensive-care unit, a string of walk-in clinics and a modern brick-and-glass building.

But on a recent weekday, it counted just 13 inpatients clustered in a single ward. The I.C.U. and maternity ward were closed for lack of staffing and the rest of the building was eerily silent, all signs of a hospital savaged by too many poor patients.

Greenwood Leflore lost $17 million last year alone and is down to a few million in cash reserves, said Gary Marchand, the hospital’s interim chief executive. “We’re going away,” he said. “It’s happening.”

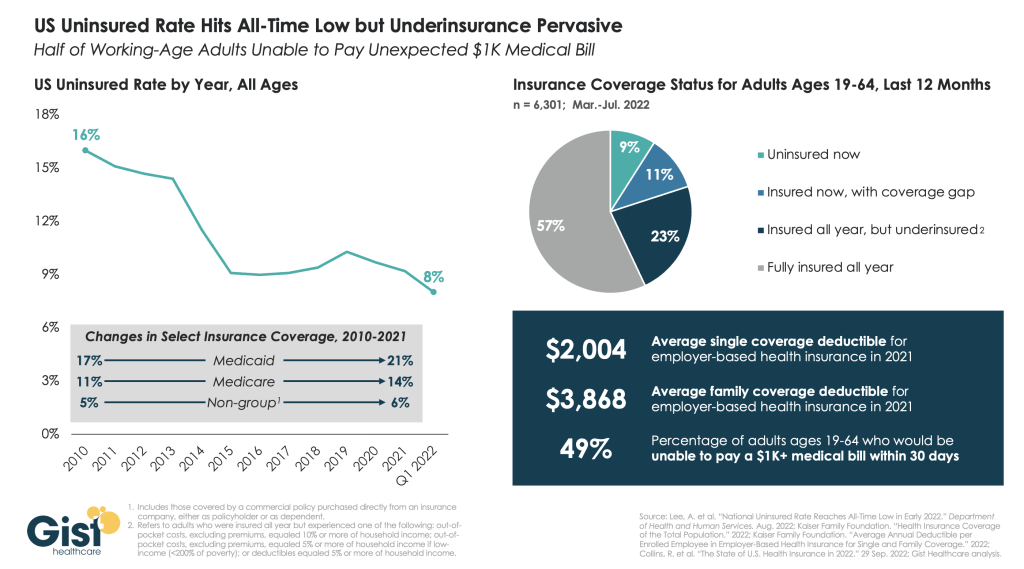

Rural hospitals are struggling all over the nation because of population declines, soaring labor costs and a long-term shift toward outpatient care. But those problems have been magnified by a political choice in Mississippi and nine other states, all with Republican-controlled legislatures.

They have spurned the federal government’s offer to shoulder almost all the cost of expanding Medicaid coverage for the poor. And that has heaped added costs on hospitals because they cannot legally turn away patients, insured or not.

States that opted against Medicaid expansion, or had just recently adopted it, accounted for nearly three-fourths of rural hospital closures between 2010 and 2021, according to the American Hospital Association.

Opponents of expansion, who have prevailed in Texas, Florida and much of the Southeast, typically say they want to keep government spending in check. States are required to put up 10 percent of the cost in order for the federal government to release the other 90 percent.

But the number of holdouts is dwindling. On Monday, North Carolina became the 40th state to expand Medicaid since the option to cover all adults with incomes below 138 percent of the poverty line opened up in 2014 under the terms of the 2010 Affordable Care Act. The law, a major victory for President Barack Obama, has continued to defy Republican efforts to kill or limit it.

“This argument about rural hospital closures has been an incredibly compelling argument to voters,” said Kelly Hall, the executive director of the Fairness Project, a national nonprofit that has successfully pushed ballot measures to expand Medicaid in seven states.

In Mississippi, one of the nation’s poorest states, the missing federal health care dollars have helped drive what is now a full-blown hospital crisis. Statewide, experts say that no more than a few of Mississippi’s 100-plus hospitals are operating at a profit. Free care is costing them about $600 million a year, the equivalent of 8 percent to 10 percent of their operating costs — a higher share than almost anywhere else in the nation, according to the state hospital association.

Expanding Medicaid would uncork a spigot of about $1.35 billion a year in federal funds to hospitals and health care providers, according to a 2021 report by the office of the state economist.

And it would guarantee medical coverage to some 100,000 uninsured adults making less than $20,120 a year in a state whose death rates are at or near the nation’s highest for heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, kidney disease and pneumonia. Infant mortality is also sky-high, and the Delta has the nation’s highest rate of foot and leg amputations because of diabetes or hypertension.

Health officials blame those numbers in part on the high rate of uninsured residents who miss out on preventive care.

“I can tell you I have a number of patients who are on dialysis with renal failure for the rest of their life because they couldn’t afford the medication for their blood pressure, and that caused their kidneys to go bad,” said Dr. John Lucas, a Greenwood Leflore surgeon.

Among Mississippi adults, only disabled people and parents with extremely low incomes, along with most pregnant women, are eligible for Medicaid. Many of the ineligible are also too poor to qualify for the tax credits for insurance under the Affordable Care Act, leaving them without affordable options.

The same is true for close to two million other Americans who live in the states that have not expanded Medicaid. Three in five are adults of color, according to a 2021 study by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonprofit research group. In Mississippi, more than half are Black.

Gov. Tate Reeves, a Republican, and key G.O.P. state lawmakers argue that a bigger Mississippi program is not in taxpayers’ best interest. The governor says the state’s $3.9 billion surplus would be best used to help eliminate Mississippi’s income tax.

“Don’t simply cave under the pressure of Democrats and their allies in the media who are pushing for the expansion of Obamacare, welfare and socialized medicine,” Mr. Reeves said in his annual State of the State address in January.

Opponents also argue that the newly insured would become dependent on Medicaid and therefore be less likely to work. “I believe we should be working to get people off Medicaid as opposed to adding more people to it,” said Philip Gunn, the powerful Republican House speaker.

Yet in Mississippi’s Delta, a flat swath of fields of corn, soybeans and other crops nearly as big as Delaware, access to any kind of medical care is drying up for lack of money. More than 300,000 people live here, nearly 35 percent of them Black. About the same percentage live in poverty, a rate three times the national average.

Dr. Daniel P. Edney, the state’s top health officer, said he did not set Medicaid policy, and he has been careful not to take sides. But he predicted emerging health care deserts where women would have to travel long distances to deliver babies and more sick people would die because they could not gain access to care.

Of the state’s hospitals, “I have maybe heard of two that are generating any profit,” he said. When he asks hospital executives if Medicaid expansion would help their balance sheets, he said, “they say it’s a game changer.”

He predicted that five hospitals would soon downgrade into mere emergency rooms, where doctors work to stabilize patients, then transfer them to the nearest hospital.

If that happens, some of the sickest will not make it, said Dr. Jeff Moses, an emergency room physician at Greenwood Leflore.

“Where are they going? Davy Jones’s locker,” he said. “It is very dark, and I’m not exaggerating this. I just can’t imagine what will happen to this community if this hospital closes.”

Nine years after states began expanding Medicaid, evidence is growing that broader coverage saves lives. In a 2021 analysis, researchers for the National Bureau of Economic Research estimated that in one four-year period, 19,200 more adults aged 55 to 64 survived because of expanded coverage, and nearly 16,000 more would have lived if that coverage was nationwide.

Other studies suggest why: Making medical care more affordable led to increases in regular checkups, cancer screenings, diagnoses of chronic diseases and prescriptions for needed medicines.

Especially during the first six years of the Medicaid expansion, when the federal government picked up 95 to 100 percent of the cost, many states found that the program was a net fiscal gain. Some states have imposed taxes on hospitals or health care providers to cover their share of the expense, the same strategy used to help fund other Medicaid costs.

Now the federal government is offering a new incentive for the holdouts: As part of a 2021 pandemic relief measure, it agreed to temporarily pay a higher proportion of costs for some existing Medicaid patients if states broadened eligibility.

Mississippi’s office of the state economist has estimated that for at least the first decade, those savings and others would fully cover the roughly $200 million a year that Medicaid expansion would cost the state government.

Tim Moore, the president of the Mississippi Hospital Association, said expansion was “a no-brainer.” The state is so poor, he said, that for every dollar it spends on Medicaid, the federal government pumps four back in.

Polls, including by Mississippi Today and Siena College, appear to show Mississippians support Medicaid expansion, regardless of their political affiliation. Brandon Presley, the Democratic candidate for governor, is highlighting hospital closures as a reason to deny Mr. Reeves a second term in elections this November.

In a possible sign of political nervousness, the governor and the legislature recently agreed to extend Medicaid coverage to pregnant women for 12 months after they give birth, prolonging a federal pandemic-era policy.

The legislators are also trying to prop up the hospitals with a one-time infusion of $83 million or more. But that is a pittance compared with what the state has given up in Medicaid payments.

The state has lost four hospitals since 2008, according to the hospital association, and Dr. Edney, the state health officer, said that it would inevitably lose more. He said he worried most about health care access in the Delta, where he grew up, the child of working-class parents with no health insurance.

On Saturday, Representative Bennie Thompson, Democrat of Mississippi, said victims of a tornado that struck the Delta last week had to be ferried 50 miles away for medical treatment because the local hospital had no power. More Medicaid dollars, he said, would have equipped it with an emergency generator.

An hour due west from Greenwood Leflore, another major hospital, run by Delta Health System, is also in serious trouble. Licensed for more than 300 beds, the hospital one day last month held just 72 inpatients.

Thirty-two of them were kept in the emergency department, partly because of nursing cuts. One upshot is that patients seeking emergency care now wait an average of two hours, four times as long as they should, according to Amy Walker, the chief nursing officer. Some simply walk out.

The neonatal intensive care unit closed last July. Now babies in trouble must be ferried by ambulance or helicopter 125 miles south to Jackson.

Iris Stacker, the chief executive, said the hospital could remain open through the end of the year; after that, she makes no promises. She is hoping federal grants will help keep the doors open, despite the state’s failure to expand Medicaid.

But she said, “It’s very hard to ask the federal government for more money when you have this pot of money sitting here that we won’t touch.”

A top message on Greenwood Leflore’s website is now a request for donations. So far, the hospital has raised less than $12,000.

Mike Hardin, a 70-year-old retiree, was one of a handful of inpatients one recent day. He had come to the emergency room two days before with slurred speech. Doctors quickly diagnosed a stroke and now were sending him home with revised medications.

“They have to do something to keep this hospital open,” he said as he was wheeled out of his room. “The people around this area wouldn’t have any place else to go.”

The hospital’s outpatient clinics are largely still in business, and doctors there say their caseloads are full of impoverished patients who should have been treated earlier.

Dr. Abhash Thakur, a cardiologist, said he routinely saw patients in the late stages of congestive heart failure who had never seen a cardiologist or been prescribed heart medication. Some have as little as 10 percent of their heart function left.

“They are not the exception,” he said, before examining a 52-year-old man who uses a wheelchair because of his heart disease. “Every day, probably, I will see a few of them.”

Dr. Raymond Girnys, a general surgeon, had just treated a man in his late 50s. He said that a week earlier, the man had punctured his foot on a sharp stick while walking in his tennis shoes in a field.

The man did not seek medical attention until the foot became infected because he was poor and uninsured. Dr. Girnys pointed out the irony: If his patient lost his foot, he would become eligible for Medicaid because then he would be disabled.

“If they had insurance, they wouldn’t be afraid to seek care,” he said.

Experts say that no more than a few of Mississippi’s 100-plus hospitals are operating at a profit.