From the Oval Office to the CDC, political and institutional failures cascaded through the system and opportunities to mitigate the pandemic were lost.

By the time Donald Trump proclaimed himself a wartime president — and the coronavirus the enemy — the United States was already on course to see more of its people die than in the wars of Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq combined.

The country has adopted an array of wartime measures never employed collectively in U.S. history — banning incoming travelers from two continents, bringing commerce to a near-halt, enlisting industry to make emergency medical gear, and confining 230 million Americans to their homes in a desperate bid to survive an attack by an unseen adversary.

Despite these and other extreme steps, the United States will likely go down as the country that was supposedly best prepared to fight a pandemic but ended up catastrophically overmatched by the novel coronavirus, sustaining heavier casualties than any other nation.

It did not have to happen this way. Though not perfectly prepared, the United States had more expertise, resources, plans and epidemiological experience than dozens of countries that ultimately fared far better in fending off the virus.

The failure has echoes of the period leading up to 9/11: Warnings were sounded, including at the highest levels of government, but the president was deaf to them until the enemy had already struck.

The Trump administration received its first formal notification of the outbreak of the coronavirus in China on Jan. 3. Within days, U.S. spy agencies were signaling the seriousness of the threat to Trump by including a warning about the coronavirus — the first of many — in the President’s Daily Brief.

And yet, it took 70 days from that initial notification for Trump to treat the coronavirus not as a distant threat or harmless flu strain well under control, but as a lethal force that had outflanked America’s defenses and was poised to kill tens of thousands of citizens. That more-than-two-month stretch now stands as critical time that was squandered.

Trump’s baseless assertions in those weeks, including his claim that it would all just “miraculously” go away, sowed significant public confusion and contradicted the urgent messages of public health experts.

“While the media would rather speculate about outrageous claims of palace intrigue, President Trump and this Administration remain completely focused on the health and safety of the American people with around the clock work to slow the spread of the virus, expand testing, and expedite vaccine development,” said Judd Deere, a spokesman for the president. “Because of the President’s leadership we will emerge from this challenge healthy, stronger, and with a prosperous and growing economy.”

The president’s behavior and combative statements were merely a visible layer on top of deeper levels of dysfunction.

The most consequential failure involved a breakdown in efforts to develop a diagnostic test that could be mass produced and distributed across the United States, enabling agencies to map early outbreaks of the disease, and impose quarantine measure to contain them. At one point, a Food and Drug Administration official tore into lab officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, telling them their lapses in protocol, including concerns that the lab did not meet the criteria for sterile conditions, were so serious that the FDA would “shut you down” if the CDC were a commercial, rather than government, entity.

Other failures cascaded through the system. The administration often seemed weeks behind the curve in reacting to the viral spread, closing doors that were already contaminated. Protracted arguments between the White House and public health agencies over funding, combined with a meager existing stockpile of emergency supplies, left vast stretches of the country’s health-care system without protective gear until the outbreak had become a pandemic. Infighting, turf wars and abrupt leadership changes hobbled the work of the coronavirus task force.

It may never be known how many thousands of deaths, or millions of infections, might have been prevented with a response that was more coherent, urgent and effective. But even now, there are many indications that the administration’s handling of the crisis had potentially devastating consequences.

Even the president’s base has begun to confront this reality. In mid-March, as Trump was rebranding himself a wartime president and belatedly urging the public to help slow the spread of the virus, Republican leaders were poring over grim polling data that suggested Trump was lulling his followers into a false sense of security in the face of a lethal threat.

The poll showed that far more Republicans than Democrats were being influenced by Trump’s dismissive depictions of the virus and the comparably scornful coverage on Fox News and other conservative networks. As a result, Republicans were in distressingly large numbers refusing to change travel plans, follow “social distancing” guidelines, stock up on supplies or otherwise take the coronavirus threat seriously.

“Denial is not likely to be a successful strategy for survival,” GOP pollster Neil Newhouse concluded in a document that was shared with GOP leaders on Capitol Hill and discussed widely at the White House. Trump’s most ardent supporters, it said, were “putting themselves and their loved ones in danger.”

Trump’s message was changing as the report swept through the GOP’s senior ranks. In recent days, Trump has bristled at reminders that he had once claimed the caseload would soon be “down to zero.”

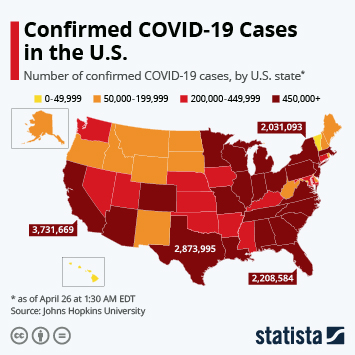

More than 7,000 people have died of the coronavirus in the United States so far, with about 240,000 cases reported. But Trump has acknowledged that new models suggest that the eventual national death toll could be between 100,000 and 240,000.

Beyond the suffering in store for thousands of victims and their families, the outcome has altered the international standing of the United States, damaging and diminishing its reputation as a global leader in times of extraordinary adversity.

“This has been a real blow to the sense that America was competent,” said Gregory F. Treverton, a former chairman of the National Intelligence Council, the government’s senior-most provider of intelligence analysis. He stepped down from the NIC in January 2017 and now teaches at the University of Southern California. “That was part of our global role. Traditional friends and allies looked to us because they thought we could be competently called upon to work with them in a crisis. This has been the opposite of that.”

This article, which retraces the failures over the first 70 days of the coronavirus crisis, is based on 47 interviews with administration officials, public health experts, intelligence officers and others involved in fighting the pandemic. Many spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive information and decisions.

Scanning the horizon

Public health authorities are part of a special breed of public servant — along with counterterrorism officials, military planners, aviation authorities and others — whose careers are consumed with contemplating worst-case scenarios.

The arsenal they wield against viral invaders is powerful, capable of smothering a new pathogen while scrambling for a cure, but easily overwhelmed if not mobilized in time. As a result, officials at the Department of Health and Human Services, the CDC and other agencies spend their days scanning the horizon for emerging dangers.

The CDC learned of a cluster of cases in China on Dec. 31 and began developing reports for HHS on Jan. 1. But the most unambiguous warning that U.S. officials received about the coronavirus came Jan. 3, when Robert Redfield, the CDC director, received a call from a counterpart in China. The official told Redfield that a mysterious respiratory illness was spreading in Wuhan, a congested commercial city of 11 million people in the communist country’s interior.

Redfield quickly relayed the disturbing news to Alex Azar, the secretary of HHS, the agency that oversees the CDC and other public health entities. Azar, in turn, ensured that the White House was notified, instructing his chief of staff to share the Chinese report with the National Security Council.

From that moment, the administration and the virus were locked in a race against a ticking clock, a competition for the upper hand between pathogen and prevention that would dictate the scale of the outbreak when it reached American shores, and determine how many would get sick or die.

The initial response was promising, but officials also immediately encountered obstacles.

On Jan. 6, Redfield sent a letter to the Chinese offering to send help, including a team of CDC scientists. China rebuffed the offer for weeks, turning away assistance and depriving U.S. authorities of an early chance to get a sample of the virus, critical for developing diagnostic tests and any potential vaccine.

China impeded the U.S. response in other ways, including by withholding accurate information about the outbreak. Beijing had a long track record of downplaying illnesses that emerged within its borders, an impulse that U.S. officials attribute to a desire by the country’s leaders to avoid embarrassment and accountability with China’s 1.3 billion people and other countries that find themselves in the pathogen’s path.

China stuck to this costly script in the case of the coronavirus, reporting Jan. 14 that it had seen “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission.” U.S. officials treated the claim with skepticism that intensified when the first case surfaced outside China with a reported infection in Thailand.

A week earlier, senior officials at HHS had begun convening an intra-agency task force including Redfield, Azar and Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The following week, there were also scattered meetings at the White House with officials from the National Security Council and State Department, focused mainly on when and whether to bring back government employees in China.

U.S. officials began taking preliminary steps to counter a potential outbreak. By mid-January, Robert Kadlec, an Air Force officer and physician who serves as assistant secretary for preparedness and response at HHS, had instructed subordinates to draw up contingency plans for enforcing the Defense Production Act, a measure that enables the government to compel private companies to produce equipment or devices critical to the country’s security. Aides were bitterly divided over whether to implement the act, and nothing happened for many weeks.

On Jan. 14, Kadlec scribbled a single word in a notebook he carries: “Coronavirus!!!”

Despite the flurry of activity at lower levels of his administration, Trump was not substantially briefed by health officials about the coronavirus until Jan.18, when, while spending the weekend at Mar-a-Lago, he took a call from Azar.

Even before the heath secretary could get a word in about the virus, Trump cut him off and began criticizing Azar for his handling of an aborted federal ban on vaping products, a matter that vexed the president.

At the time, Trump was in the throes of an impeachment battle over his alleged attempt to coerce political favors from the leader of Ukraine. Acquittal seemed certain by the GOP-controlled Senate, but Trump was preoccupied with the trial, calling lawmakers late at night to rant, and making lists of perceived enemies he would seek to punish when the case against him concluded.

In hindsight, officials said, Azar could have been more forceful in urging Trump to turn at least some of his attention to a threat that would soon pose an even graver test to his presidency, a crisis that would cost American lives and consume the final year of Trump’s first term.

But the secretary, who had a strained relationship with Trump and many others in the administration, assured the president that those responsible were working on and monitoring the issue. Azar told several associates that the president believed he was “alarmist” and Azar struggled to get Trump’s attention to focus on the issue, even asking one confidant for advice.

Within days, there were new causes for alarm.

On Jan. 21, a Seattle man who had recently traveled to Wuhan tested positive for the coronavirus, becoming the first known infection on U.S. soil. Then, two days later, Chinese authorities took the drastic step of shutting down Wuhan, turning the teeming metropolis into a ghost city of empty highways and shuttered skyscrapers, with millions of people marooned in their homes.

“That was like, whoa,” said a senior U.S. official involved in White House meetings on the crisis. “That was when the Richter scale hit 8.”

It was also when U.S. officials began to confront the failings of their own efforts to respond.

Azar, who had served in senior positions at HHS through crises including the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the outbreak of bird flu in 2005, was intimately familiar with the playbook for crisis management.

He instructed subordinates to move rapidly to establish a nationwide surveillance system to track the spread of the coronavirus — a stepped-up version of what the CDC does every year to monitor new strains of the ordinary flu.

But doing so would require assets that would elude U.S. officials for months — a diagnostic test that could accurately identify those infected with the new virus and be produced on a mass scale for rapid deployment across the United States, and money to implement the system.

Azar’s team also hit another obstacle. The Chinese were still refusing to share the viral samples they had collected and were using to develop their own tests. In frustration, U.S. officials looked for other possible routes.

A biocontainment lab at the University of Texas medical branch in Galveston had a research partnership with the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

Kadlec, who knew the Galveston lab director, hoped scientists could arrange a transaction on their own without government interference. At first, the lab in Wuhan agreed, but officials in Beijing intervened Jan. 24 and blocked any lab-to-lab transfer.

There is no indication that officials sought to escalate the matter or enlist Trump to intervene. In fact, Trump has consistently praised Chinese President Xi Jinping despite warnings from U.S. intelligence and health officials that Beijing was concealing the true scale of the outbreak and impeding cooperation on key fronts.

The CDC had issued its first public alert about the coronavirus Jan. 8, and by the 17th was monitoring major airports in Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York, where large numbers of passengers arrived each day from China.

In other ways, though, the situation was already spinning out of control, with multiplying cases in Seattle, intransigence by the Chinese, mounting questions from the public, and nothing in place to stop infected travelers from arriving from abroad.

Trump was out of the country for this critical stretch, taking part in the annual global economic forum in Davos, Switzerland. He was accompanied by a contingent of top officials including national security adviser Robert O’Brien, who took an anxious trans-Atlantic call from Azar.

Azar told O’Brien that it was “mayhem” at the White House, with HHS officials being pressed to provide nearly identical briefings to three audiences on the same day.

Azar urged O’Brien to have the NSC assert control over a matter with potential implications for air travel, immigration authorities, the State Department and the Pentagon. O’Brien seemed to grasp the urgency, and put his deputy, Matthew Pottinger, who had worked in China as a journalist for the Wall Street Journal, in charge of coordinating the still-nascent U.S. response.

But the rising anxiety within the administration appeared not to register with the president. On Jan. 22, Trump received his first question about the coronavirus in an interview on CNBC while in Davos. Asked whether he was worried about a potential pandemic, Trump said, “No. Not at all. And we have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China. . . . It’s going to be just fine.”

Spreading uncontrollably

The move by the NSC to seize control of the response marked an opportunity to reorient U.S. strategy around containing the virus where possible and procuring resources that hospitals would need in any U.S. outbreak, including such basic equipment as protective masks and ventilators.

But instead of mobilizing for what was coming, U.S. officials seemed more preoccupied with logistical problems, including how to evacuate Americans from China.

In Washington, then-acting chief of staff Mick Mulvaney and Pottinger began convening meetings at the White House with senior officials from HHS, the CDC and the State Department.

The group, which included Azar, Pottinger and Fauci, as well as nine others across the administration, formed the core of what would become the administration’s coronavirus task force. But it primarily focused on efforts to keep infected people in China from traveling to the United States even while evacuating thousands of U.S. citizens. The meetings did not seriously focus on testing or supplies, which have since become the administration’s most challenging problems.

The task force was formally announced on Jan. 29.

“The genesis of this group was around border control and repatriation,” said a senior official involved in the meetings. “It wasn’t a comprehensive, whole-of-government group to run everything.”

The State Department agenda dominated those early discussions, according to participants. Officials began making plans to charter aircraft to evacuate 6,000 Americans stranded in Wuhan. They also debated language for travel advisories that State could issue to discourage other travel in and out of China.

On Jan. 29, Mulvaney chaired a meeting in the White House Situation Room in which officials debated moving travel restrictions to “Level 4,” meaning a “do not travel” advisory from the State Department. Then, the next day, China took the draconian step of locking down the entire Hubei province, which encompasses Wuhan.

That move by Beijing finally prompted a commensurate action by the Trump administration. On Jan. 31, Azar announced restrictions barring any non-U.S. citizen who had been in China during the preceding two weeks from entering the United States.

Trump has, with some justification, pointed to the China-related restriction as evidence that he had responded aggressively and early to the outbreak. It was among the few intervention options throughout the crisis that played to the instincts of the president, who often seems fixated on erecting borders and keeping foreigners out of the country.

But by that point, 300,000 people had come into the United States from China over the previous month. There were only 7,818 confirmed cases around the world at the end of January, according to figures released by the World Health Organization — but it is now clear that the virus was spreading uncontrollably.

Pottinger was by then pushing for another travel ban, this time restricting the flow of travelers from Italy and other nations in the European Union that were rapidly emerging as major new nodes of the outbreak. Pottinger’s proposal was endorsed by key health-care officials, including Fauci, who argued that it was critical to close off any path the virus might take into the country.

This time, the plan met with resistance from Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and others who worried about the impact on the U.S. economy. It was an early sign of tension in an area that would split the administration, pitting those who prioritized public health against those determined to avoid any disruption in an election year to the run of expansion and employment growth.

Those backing the economy prevailed with the president. And it was more than a month before the administration issued a belated and confusing ban on flights into the United States from Europe. Hundreds of thousands of people crossed the Atlantic during that interval.

A wall of resistance

While fights over air travel played out in the White House, public health officials began to panic over a startling shortage of critical medical equipment including protective masks for doctors and nurses, as well as a rapidly shrinking pool of money needed to pay for such things.

By early February, the administration was quickly draining a $105 million congressional fund to respond to infectious disease outbreaks. The coronavirus threat to the United States still seemed distant if not entirely hypothetical to much of the public. But to health officials charged with stockpiling supplies for worst-case-scenarios, disaster appeared increasingly inevitable.

A national stockpile of N95 protective masks, gowns, gloves and other supplies was already woefully inadequate after years of underfunding. The prospects for replenishing that store were suddenly threatened by the unfolding crisis in China, which disrupted offshore supply chains.

Much of the manufacturing of such equipment had long since migrated to China, where factories were now shuttered because workers were on order to stay in their households. At the same time, China was buying up masks and other gear to gird for its own coronavirus outbreak, driving up costs and monopolizing supplies.

In late January and early February, leaders at HHS sent two letters to the White House Office of Management and Budget asking to use its transfer authority to shift $136 million of department funds into pools that could be tapped for combating the coronavirus. Azar and his aides also began raising the need for a multibillion-dollar supplemental budget request to send to Congress.

Yet White House budget hawks argued that appropriating too much money at once when there were only a few U.S. cases would be viewed as alarmist.

Joe Grogan, head of the Domestic Policy Council, clashed with health officials over preparedness. He mistrusted how the money would be used and questioned how health officials had used previous preparedness funds.

Azar then spoke to Russell Vought, the acting director of the White House Office of Management and Budget, during Trump’s State of the Union speech on Feb. 4. Vought seemed amenable, and told Azar to submit a proposal.

Azar did so the next day, drafting a supplemental request for more than $4 billion, a sum that OMB officials and others at the White House greeted as an outrage. Azar arrived at the White House that day for a tense meeting in the Situation Room that erupted in a shouting match, according to three people familiar with the incident.

A deputy in the budget office accused Azar of preemptively lobbying Congress for a gigantic sum that White House officials had no interest in granting. Azar bristled at the criticism and defended the need for an emergency infusion. But his standing with White House officials, already shaky before the coronavirus crisis began, was damaged further.

White House officials relented to a degree weeks later as the feared coronavirus surge in the United States began to materialize. The OMB team whittled Azar’s demands down to $2.5 billion, money that would be available only in the current fiscal year. Congress ignored that figure, approving an $8 billion supplemental bill that Trump signed into law March 7.

But again, delays proved costly. The disputes meant that the United States missed a narrow window to stockpile ventilators, masks and other protective gear before the administration was bidding against many other desperate nations, and state officials fed up with federal failures began scouring for supplies themselves.

In late March, the administration ordered 10,000 ventilators — far short of what public health officials and governors said was needed. And many will not arrive until the summer or fall, when models expect the pandemic to be receding.

“It’s actually kind of a joke,” said one administration official involved in deliberations about the belated purchase.

Inconclusive tests

Although viruses travel unseen, public health officials have developed elaborate ways of mapping and tracking their movements. Stemming an outbreak or slowing a pandemic in many ways comes down to the ability to quickly divide the population into those who are infected and those who are not.

Doing so, however, hinges on having an accurate test to diagnose patients and deploy it rapidly to labs across the country. The time it took to accomplish that in the United States may have been more costly to American efforts than any other failing.

“If you had the testing, you could say, ‘Oh my god, there’s circulating virus in Seattle, let’s jump on it. There’s circulating virus in Chicago, let’s jump on it,’ ” said a senior administration official involved in battling the outbreak. “We didn’t have that visibility.”

The first setback came when China refused to share samples of the virus, depriving U.S. researchers of supplies to bombard with drugs and therapies in a search for ways to defeat it. But even when samples had been procured, the U.S. effort was hampered by systemic problems and institutional hubris.

Among the costliest errors was a misplaced assessment by top health officials that the outbreak would probably be limited in scale inside the United States — as had been the case with every other infection for decades — and that the CDC could be trusted on its own to develop a coronavirus diagnostic test.

The CDC, launched in the 1940s to contain an outbreak of malaria in the southern United States, had taken the lead on the development of diagnostic tests in major outbreaks including Ebola, zika and H1N1. But the CDC was not built to mass-produce tests.

The CDC’s success had fostered an institutional arrogance, a sense that even in the face of a potential crisis there was no pressing need to involve private labs, academic institutions, hospitals and global health organizations also capable of developing tests.

Yet some were concerned that the CDC test would not be enough. Stephen Hahn, the FDA commissioner, sought authority in early February to begin calling private diagnostic and pharmaceutical companies to enlist their help.

But when senior FDA officials consulted leaders at HHS, Hahn, who had led the agency for about two months, was told to stand down. There were concerns about him personally contacting companies regulated by his agency.

At that point, Azar, the HHS secretary, seemed committed to a plan he was pursuing that would keep his agency at the center of the response effort: securing a test from the CDC and then building a national coronavirus surveillance system by relying on an existing network of labs used to track the ordinary flu.

In task force meetings, Azar and Redfield pushed for $100 million to fund the plan, but were shot down because of the cost, according to a document outlining the testing strategy obtained by The Washington Post.

Relying so heavily on the CDC would have been problematic even if it had succeeded in quickly developing an effective test that could be distributed across the country. The scale of the epidemic, and the need for mass testing far beyond the capabilities of the flu network, would have overwhelmed Azar’s plan, which didn’t envision engaging commercial lab companies for up to six months.

The effort collapsed when the CDC failed its basic assignment to create a working test and the task force rejected Azar’s plan.

On Feb. 6, when the World Health Organization reported that it was shipping 250,000 test kits to labs around the world, the CDC began distributing 90 kits to a smattering of state-run health labs.

Almost immediately, the state facilities encountered problems. The results were inconclusive in trial runs at more than half the labs, meaning they couldn’t be relied upon to diagnose actual patients. The CDC issued a stopgap measure, instructing labs to send tests to its headquarters in Atlanta, a practice that would delay results for days.

The scarcity of effective tests led officials to impose constraints on when and how to use them, and delayed surveillance testing. Initial guidelines were so restrictive that states were discouraged from testing patients exhibiting symptoms unless they had traveled to China and come into contact with a confirmed case, when the pathogen had by that point almost certainly spread more broadly into the general population.

The limits left top officials largely blind to the true dimensions of the outbreak.

In a meeting in the Situation Room in mid-February, Fauci and Redfield told White House officials that there was no evidence yet of worrisome person-to-person transmission in the United States. In hindsight, it appears almost certain that the virus was taking hold in communities at that point. But even the country’s top experts had little meaningful data about the domestic dimensions of the threat. Fauci later conceded that as they learned more their views changed.

At the same time, the president’s subordinates were growing increasingly alarmed, Trump continued to exhibit little concern. On Feb. 10, he held a political rally in New Hampshire attended by thousands where he declared that “by April, you know, in theory, when it gets a little warmer, it miraculously goes away.”

The New Hampshire rally was one of eight that Trump held after he had been told by Azar about the coronavirus, a period when he also went to his golf courses six times.

A day earlier, on Feb. 9, a group of governors in town for a black-tie gala at the White House secured a private meeting with Fauci and Redfield. The briefing rattled many of the governors, bearing little resemblance to the words of the president. “The doctors and the scientists, they were telling us then exactly what they are saying now,” Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan (R) said.

That month, federal medical and public health officials were emailing increasingly dire forecasts among themselves, with one Veterans Affairs medical adviser warning, ‘We are flying blind,’” according to emails obtained by the watchdog group American Oversight.

Later in February, U.S. officials discovered indications that the CDC laboratory was failing to meet basic quality-control standards. On a Feb. 27 conference call with a range of health officials, a senior FDA official lashed out at the CDC for its repeated lapses.

Jeffrey Shuren, the FDA’s director for devices and radiological health, told the CDC that if it were subjected to the same scrutiny as a privately run lab, “I would shut you down.”

On Feb. 29, a Washington state man became the first American to die of a coronavirus infection. That same day, the FDA released guidance, signaling that private labs were free to proceed in developing their own diagnostics.

Another four-week stretch had been squandered.

Life and death

One week later, on March 6, Trump toured the facilities at the CDC wearing a red “Keep America Great” hat. He boasted that the CDC tests were nearly perfect and that “anybody who wants a test will get a test,” a promise that nearly a month later remains unmet.

He also professed to have a keen medical mind. “I like this stuff. I really get it,” he said. “People here are surprised that I understand it. Every one of these doctors said, ‘How do you know so much about this?’ ”

In reality, many of the failures to stem the coronavirus outbreak in the United States were either a result of, or exacerbated by, his leadership.

For weeks, he had barely uttered a word about the crisis that didn’t downplay its severity or propagate demonstrably false information. He dismissed the warnings of intelligence officials and top public health officials in his administration.

At times, he voiced far more authentic concern about the trajectory of the stock market than the spread of the virus in the United States, railing at the chairman of the Federal Reserve and others with an intensity that he never seemed to exhibit about the possible human toll of the outbreak.

In March, as state after state imposed sweeping new restrictions on their citizens’ daily lives to protect them — triggering severe shudders in the economy — Trump second-guessed the lockdowns.

The common flu kills tens of thousands each year and “nothing is shut down, life & the economy go on,” he tweeted March 9. A day later, he pledged that the virus would “go away. Just stay calm.”

Two days later, Trump finally ordered the halt to incoming travel from Europe that his deputy national security adviser had been advocating for weeks. But Trump botched the Oval Office announcement so badly that White House officials spent days trying to correct erroneous statements that triggered a stampede by U.S. citizens overseas to get home.

“There was some coming to grips with the problem and the true nature of it — the 13th of March is when I saw him really turn the corner. It took a while to realize you’re at war,” Sen. Lindsey O. Graham (R-S.C.) said. “That’s when he took decisive action that set in motion some real payoffs.”

Trump spent many weeks shuffling responsibility for leading his administration’s response to the crisis, putting Azar in charge of the task force at first, relying on Pottinger, the deputy national security adviser, for brief periods, before finally putting Vice President Pence in the role toward the end of February.

Other officials have emerged during the crisis to help right the United States’ course, and at times, the statements of the president. But even as Fauci, Azar and others sought to assert themselves, Trump was behind the scenes turning to others with no credentials, experience or discernible insight in navigating a pandemic.

Foremost among them was his adviser and son-in-law, Jared Kushner. A team reporting to Kushner commandeered space on the seventh floor of the HHS building to pursue a series of inchoate initiatives.

One plan involved having Google create a website to direct those with symptoms to testing facilities that were supposed to spring up in Walmart parking lots across the country, but which never materialized. Another centered an idea advanced by Oracle chairman Larry Ellison to use software to monitor the unproven use of anti-malaria drugs against the coronavirus pathogen.

So far, the plans have failed to come close to delivering on the promises made when they were touted in White House news conferences. The Kushner initiatives have, however, often interrupted the work of those under immense pressure to manage the U.S. response.

Current and former officials said that Kadlec, Fauci, Redfield and others have repeatedly had to divert their attentions from core operations to contend with ill-conceived requests from the White House they don’t believe they can ignore. And Azar, who once ran the response, has since been sidelined, with his agency disempowered in decision-making and his performance pilloried by a range of White House officials, including Kushner.

“Right now Fauci is trying to roll out the most ambitious clinical trial ever implemented” to hasten the development of a vaccine, said a former senior administration official in frequent touch with former colleagues. And yet, the nation’s top health officials “are getting calls from the White House or Jared’s team asking, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice to do this with Oracle?’ ”

If the coronavirus has exposed the country’s misplaced confidence in its ability to handle a crisis, it also has cast harsh light on the limits of Trump’s approach to the presidency — his disdain for facts, science and experience.

He has survived other challenges to his presidency — including the Russia investigation and impeachment — by fiercely contesting the facts arrayed against him and trying to control the public’s understanding of events with streams of falsehoods.

The coronavirus may be the first crisis Trump has faced in office where the facts — the thousands of mounting deaths and infections — are so devastatingly evident that they defy these tactics.

After months of dismissing the severity of the coronavirus, resisting calls for austere measures to contain it, and recasting himself as a wartime president, Trump seemed finally to succumb to the coronavirus reality. In a meeting with a Republican ally in the Oval Office last month, the president said his campaign no longer mattered because his reelection would hinge on his coronavirus response.

“It’s absolutely critical for the American people to follow the guidelines for the next 30 days,” he said at his March 31 news conference. “It’s a matter of life and death.”