Since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, Florida has blocked, obscured, delayed, and at times hidden the COVID-19 data used in making big decisions such as reopening schools and businesses.

And with scientists warning Thanksgiving gatherings could cause an explosion of infections, the shortcomings in the state’s viral reporting have yet to be fixed.

While the state has put out an enormous amount of information, some of its actions have raised concerns among researchers that state officials are being less than transparent.

It started even before the pandemic became a daily concern for millions of residents. Nearly 175 patients tested positive for the disease in January and February, evidence the Florida Department of Health collected but never acknowledged or explained. The state fired its nationally praised chief data manager, she says in a whistleblower lawsuit, after she refused to manipulate data to support premature reopening. The state said she was fired for not following orders.

The health department used to publish coronavirus statistics twice a day before changing to once a day, consistently meeting an 11 a.m. daily deadline for releasing new information that scientists, the media and the public could use to follow the pandemic’s latest twists.

But in the past month the department has routinely and inexplicably failed to meet its own deadline by as much as six hours. On one day in October, it published no update at all.

News outlets were forced to sue the state before it would publish information identifying the number of infections and deaths at individual nursing homes.

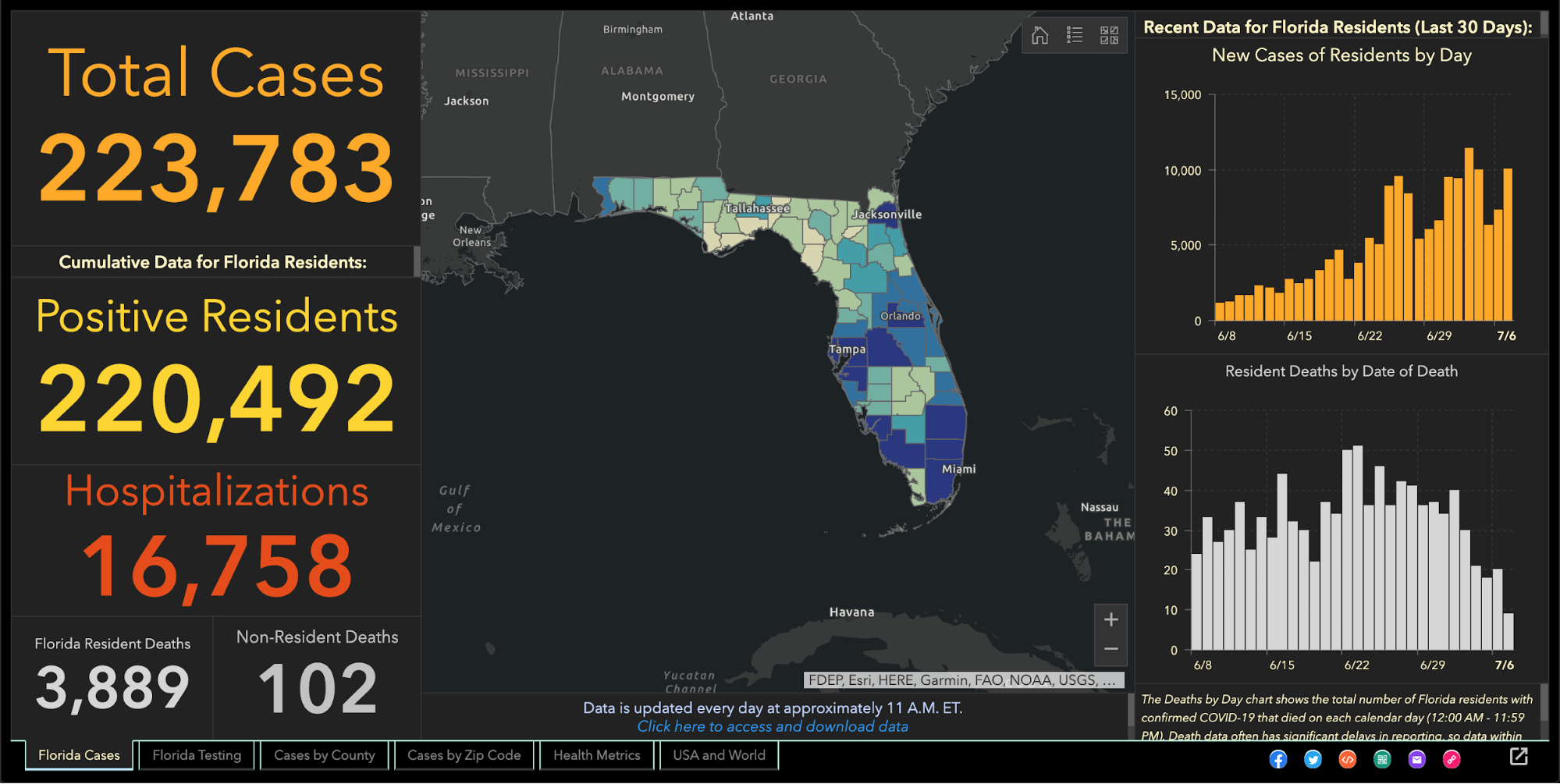

Throughout it all, the state has kept up with the rapidly spreading virus by publishing daily updates of the numbers of cases, deaths and hospitalizations.

“Florida makes a lot of data available that is a lot of use in tracking the pandemic,” University of South Florida epidemiologist Jason Salemi said. “They’re one of the only states, if not the only state, that releases daily case line data (showing age, sex and county for each infected person).”

Dr. Terry Adirim, chairwoman of Florida Atlantic University’s Department of Integrated Biomedical Science, agreed, to a point.

“The good side is they do have daily spreadsheets,” Adirim said. “However, it’s the data that they want to put out.”

The state leaves out crucial information that could help the public better understand who the virus is hurting and where it is spreading, Adirim said.

The department, under state Surgeon General Dr. Scott Rivkees, oversees 53? health agencies covering Florida’s 67 counties, such as the one in Palm Beach County headed by Dr. Alina Alonso.

Rivkees was appointed in April 2019. He reports to Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican who has supported President Donald Trump’s approach to fighting the coronavirus and pressured local officials to reopen schools and businesses despite a series of spikes indicating rapid spread of the disease.

At several points, the DeSantis administration muzzled local health directors, such as when it told them not to advise school boards on reopening campuses.

DOH Knew Virus Here Since January

The health department’s own coronavirus reports indicated that the pathogen had been infecting Floridians since January, yet health officials never informed the public about it and they did not publicly acknowledge it even after The Palm Beach Post first reported it in May.

In fact, the night before The Post broke the story, the department inexplicably removed from public view the state’s dataset that provided the evidence. Mixed among listings of thousands of cases was evidence that up to 171 people ages 4 to 91 had tested positive for COVID-19 in the months before officials announced in March the disease’s presence in the state.

Were the media reports on the meaning of those 171 cases in error? The state has never said.

No Testing Stats Initially

When positive tests were finally acknowledged in March, all tests had to be confirmed by federal health officials. But Florida health officials refused to even acknowledge how many people in each county had been tested.

State health officials and DeSantis claimed they had to withhold the information to protect patient privacy, but they provided no evidence that stating the number of people tested would reveal personal information.

At the same time, the director of the Hillsborough County branch of the state health department publicly revealed that information to Hillsborough County commissioners.

And during March the state published on a website that wasn’t promoted to the public the ages and genders of those who had been confirmed to be carrying the disease, along with the counties where they claimed residence.

Firing Coronavirus Data Chief

In May, with the media asking about data that revealed the earlier onset of the disease, internal emails show that a department manager ordered the state’s coronavirus data chief to yank the information off the web, even though it had been online for months.

A health department tech supervisor told data manager Rebekah Jones on May 5 to take down the dataset. Jones replied in an email that was the “wrong call,” but complied, only to be ordered an hour later to put it back.

That day, she emailed reporters and researchers following a listserv she created, saying she had been removed from handling coronavirus data because she refused to manipulate datasets to justify DeSantis’ push to begin reopening businesses and public places.

Two weeks later, the health department fired Jones, who in March had created and maintained Florida’s one-stop coronavirus dashboard, which had been viewed by millions of people, and had been praised nationally, including by White House Coronavirus Task Force Coordinator Deborah Birx.

The dashboard allows viewers to explore the total number of coronavirus cases, deaths, tests and other information statewide and by county and across age groups and genders.

DeSantis claimed on May 21 that Jones wanted to upload bad coronavirus data to the state’s website. To further attempt to discredit her, he brought up stalking charges made against her by an ex-lover, stemming from a blog post she wrote, that led to two misdemeanor charges.

Using her technical know-how, Jones launched a competing COVID-19 dashboard website, FloridaCOVIDAction.com in early June. After national media covered Jones’ firing and website launch, people donated more than $200,000 to her through GoFundMe to help pay her bills and maintain the website.

People view her site more than 1 million times a day, she said. The website features the same type of data the state’s dashboard displays, but also includes information not present on the state’s site such as a listing of testing sites and their contact information.

Jones also helped launch TheCOVIDMonitor.com to collect reports of infections in schools across the country.

Jones filed a whistleblower complaint against the state in July, accusing managers of retaliating against her for refusing to change the data to make the coronavirus situation look better.

“The Florida Department of Health needs a data auditor not affiliated with the governor’s office because they cannot be trusted,” Jones said Friday.

Florida Hides Death Details

When coronavirus kills someone, their county’s medical examiner’s office logs their name, age, ethnicity and other information, and sends it to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement.

During March and April, the department refused requests to release that information to the public, even though medical examiners in Florida always have made it public under state law. Many county medical examiners, acknowledging the role that public information can play in combating a pandemic, released the information without dispute.

But it took legal pressure from news outlets, including The Post, before FDLE agreed to release the records it collected from local medical examiners.

When FDLE finally published the document on May 6, it blacked out or excluded crucial information such as each victim’s name or cause of death.

But FDLE’s attempt to obscure some of that information failed when, upon closer examination, the seemingly redacted details could in fact be read by common computer software.

Outlets such as Gannett, which owns The Post, and The New York Times, extracted the data invisible to the naked eye and reported in detail what the state redacted, such as the details on how each patient died.

Reluctantly Revealing Elder Care Deaths, Hospitalizations

It took a lawsuit against the state filed by the Miami Herald, joined by The Post and other news outlets, before the health department began publishing the names of long-term care facilities with the numbers of coronavirus cases and deaths.

The publication provided the only official source for family members to find out how many people had died of COVID-19 at the long-term care facility housing their loved ones.

While the state agreed to publish the information weekly, it has failed to publish several times and as of Nov. 24 had not updated the information since Nov. 6.

It took more pressure from Florida news outlets to pry from the state government the number of beds in each hospital being occupied by coronavirus patients, a key indicator of the disease’s spread, DeSantis said.

That was one issue where USF’s Salemi publicly criticized Florida.

“They were one of the last three states to release that information,” he said. “That to me is a problem because it is a key indicator.”

Confusion Over Positivity Rate

One metric DeSantis touted to justify his decision in May to begin reopening Florida’s economy was the so-called positivity rate, which is the share of tests reported each day with positive results.

But Florida’s daily figures contrasted sharply with calculations made by Johns Hopkins University, prompting a South Florida Sun-Sentinel examination that showed Florida’s methodology underestimated the positivity rate.

The state counts people who have tested positive only once, but counts every negative test a person receives until they test positive, so that there are many more negative tests for every positive one.

John Hopkins University, on the other hand, calculated Florida’s positivity rate by comparing the number of people testing positive with the total number of people who got tested for the first time.

By John Hopkins’ measure, between 10 and 11 percent of Florida’s tests in October came up positive, compared to the state’s reported rate of between 4 and 5 percent.

Health experts such as those at the World Health Organization have said a state’s positivity rate should stay below 5 percent for 14 days straight before it considers the virus under control and go forward with reopening public places and businesses. It’s also an important measure for travelers, who may be required to quarantine if they enter a state with a high positivity rate.

Withholding Detail on Race, Ethnicity

The Post reported in June that the share of tests taken by Black and Hispanic people and in majority minority ZIP codes were twice as likely to come back positive compared to tests conducted on white people and in majority white ZIP codes.

That was based on a Post analysis of internal state data the health department will not share with the public.

The state publishes bar charts showing general racial breakdowns but not for each infected person.

If it wanted to, Florida’s health department could publish detailed data that would shed light on the infection rates among each race and ethnicity or each age group, as well as which neighborhoods are seeing high rates of contagion.

Researchers have been trying to obtain this data but “the state won’t release the data without (making us) undergo an arduous data use agreement application process with no guarantee of release of the data,” Adirim said. Researchers must read and sign a 26-page, nearly 5,700-word agreement before getting a chance at seeing the raw data.

While Florida publishes the ages, genders and counties of residence for each infected person, “there’s no identification for race or ethnicity, no ZIP code or city of the residence of the patient,” Adirim said. “No line item count of negative test data so it’s hard to do your own calculation of test positivity.”

While Florida doesn’t explain its reasoning, one fear of releasing such information is the risk of identifying patients, particularly in tiny, non-diverse counties.

Confusion Over Lab Results

Florida’s daily report shows how many positive results come from each laboratory statewide. Except when it doesn’t.

The report has shown for months that 100 percent of COVID-19 tests conducted by some labs have come back positive despite those labs saying that shouldn’t be the case.

While the department reported in July that all 410 results from a Lee County lab were positive, a lab spokesman told The Post the lab had conducted roughly 30,000 tests. Other labs expressed the same confusion when informed of the state’s reporting.

The state health department said it would work with labs to fix the error. But even as recently as Tuesday, the state’s daily report showed positive result rates of 100 percent or just under it from some labs, comprising hundreds of tests.

Mistakenly Revealing School Infections

As DeSantis pushed in August for reopening schools and universities for students to attend in-person classes, Florida’s health department published a report showing hundreds of infections could be traced back to schools, before pulling that report from public view.

The health department claimed it published that data by mistake, the Miami Herald reported.

The report showed that COVID-19 had infected nearly 900 students and staffers.

The state resumed school infection reporting in September.

A similar publication of cases at day-care centers appeared online briefly in August only to come down permanently.

Updates Delayed

After shifting in late April to updating the public just once a day at 11 a.m. instead of twice daily, the state met that deadline on most days until it started to falter in October. Pandemic followers could rely on the predictability.

On Oct. 10, the state published no data at all, not informing the public of a problem until 5 p.m.

The state blamed a private lab for the failure but the next day retracted its statement after the private lab disputed the state’s explanation. No further explanation has been offered.

On Oct. 21, the report came out six hours late.

Since Nov. 3, the 11 a.m. deadline has never been met. Now, late afternoon releases have become the norm.

“They have gotten more sloppy and they have really dragged their feet,” Adirim, the FAU scientist, said.

No spokesperson for the health department has answered questions from The Post to explain the lengthy delays. Alberto Moscoso, the spokesman throughout the pandemic, departed without explanation Nov. 6.

The state’s tardiness can trip up researchers trying to track the pandemic in Florida, Adirim said, because if one misses a late-day update, the department could overwrite it with another update the next morning, eliminating critical information and damaging scientists’ analysis.

Hired Sports Blogger to Analyze Data

As if to show disregard for concerns raised by scientists, the DeSantis administration brought in a new data analyst who bragged online that he is no expert and doesn’t need to be.

Kyle Lamb, an Uber driver and sports blogger, sees his lack of experience as a plus.

“Fact is, I’m not an ‘expert’,” Lamb wrote on a website for a subscribers-only podcast he hosts about the coronavirus. “I also don’t need to be. Experts don’t have all the answers, and we’ve learned that the hard way throughout the entire duration of the global pandemic.”

Much of his coronavirus writings can be found on Twitter, where he has said masks and mandatory quarantines don’t stop the virus’ spread, and that hydroxychloroquine, a drug touted by President Donald Trump but rejected by medical researchers, treats it successfully.

While DeSantis says lockdowns aren’t effective in stopping the spread and refuses to enact a statewide mask mandate, scientists point out that quarantines and masks are extremely effective.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has said hydroxychloroquine is unlikely to help and poses greater risk to patients than any potential benefits.

Coronavirus researchers have called Lamb’s views “laughable,” and fellow sports bloggers have said he tends to act like he knows much about a subject in which he knows little, the Miami Herald reported.

DeSantis has yet to explain how and why Lamb was hired, nor has his office released Lamb’s application for the $40,000-a-year job. “We generally do not comment on such entry level hirings,” DeSantis spokesman Fred Piccolo said Tuesday by email.

It could be worse.

Texas health department workers have to manually enter data they read from paper faxes into the state’s coronavirus tracking system, The Texas Tribune has reported. And unlike Florida, Texas doesn’t require local health officials to report viral data to the state in a uniform way that would make it easier and faster to process and report.

It could be better.

In Wisconsin, health officials report the number of cases and deaths down to the neighborhood level. They also plainly report racial and ethnic disparities, which show the disease hits Hispanic residents hardest.

Still, Salemi worries that Florida’s lack of answers can undermine residents’ faith.

“My whole thing is the communication, the transparency,” Salemi said. “Just let us know what’s going on. That can stop people from assuming the worst. Even if you make a big error people are a lot more forgiving, whereas if the only time you’re communicating is when bad things happen … people start to wonder.”