Twenty-five percent of the 1,430 rural hospitals in the U.S. are at high risk of closing unless their finances improve, according to an annual analysis from Guidehouse, a consulting firm.

The 354 rural hospitals at high risk of closing are spread across 40 states and represent more than 222,000 annual discharges. According to the analysis, 287 of these hospitals — 81 percent — are considered highly essential to the health and economic wellbeing of their communities.

Several factors are putting rural hospitals at risk of closing, according to the analysis, which looked at operating margin, days cash on hand, debt-to-capitalization ratio, current ratio and inpatient census to determine the financial viability of rural hospitals. Declining inpatient volume, clinician shortages, payer mix degradation and revenue cycle management challenges are among the factors driving the rural hospital crisis.

The Guidehouse study analyzed the financial viability of rural hospitals prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the authors noted that the rural hospital crisis could significantly worsen due to the pandemic or any downturn in the economy.

Here are the number and percentage of rural hospitals at high risk of closing in each state based on the analysis:

Tennessee

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 19 (68 percent)

Alabama

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 18 (60 percent)

Oklahoma

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 28 (60 percent)

Arkansas

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 18 (53 percent)

Mississippi

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 25 (50 percent)

West Virginia

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 9 (50 percent)

South Carolina

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 4 (44 percent)

Georgia

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 14 (41 percent)

Kentucky

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 18 (40 percent)

Louisiana

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 11 (37 percent)

Maine

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 7 (33 percent)

Indiana

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 8 (31 percent)

Kansas

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 26 (31 percent)

New Mexico

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 3 (30 percent)

Michigan

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 13 (29 percent)

Missouri

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 10 (26 percent)

Virginia

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 5 (25 percent)

Oregon

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 4 (24 percent)

California

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 6 (23 percent)

North Carolina

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 6 (23 percent)

Florida

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 2 (22 percent)

North Dakota

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 7 (21 percent)

Ohio

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 6 (20 percent)

Vermont

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 2 (20 percent)

Idaho

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 4 (19 percent)

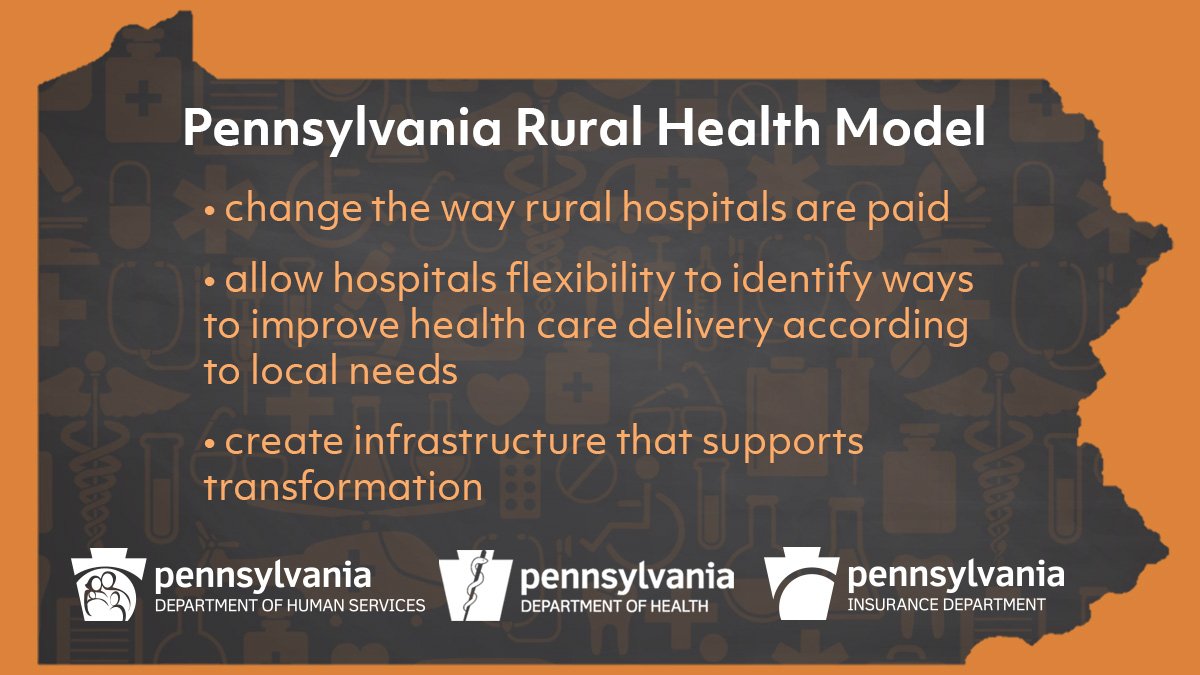

Pennsylvania

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 4 (19 percent)

Washington

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 5 (18 percent)

Wyoming

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 3 (18 percent)

Texas

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 14 (16 percent)

Colorado

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 4 (14 percent)

Illinois

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 7 (14 percent)

Montana

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 7 (14 percent)

Nebraska

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 8 (13 percent)

New York

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 4 (13 percent)

Iowa

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 9 (12 percent)

Minnesota

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 8 (11 percent)

Alaska

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 1 (10 percent)

Arizona

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 1 (10 percent)

New Hampshire

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 1 (9 percent)

Wisconsin

Rural hospitals at high risk of closing: 5 (9 percent)