https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2020/04/us-coronavirus-outbreak-out-control-test-positivity-rate/610132/

Few figures tell you anything useful about how the coronavirus has spread through the U.S. Here’s one that does.

How many people have the coronavirus in the United States? More than two months into the country’s outbreak, this remains the most important question for its people, schools, hospitals, and businesses. It is also still among the hardest to answer. At least 630,000 people nationwide now have test-confirmed cases of COVID-19, according to The Atlantic’s COVID Tracking Project, a state-by-state tally conducted by more than 100 volunteers and experts. But an overwhelming body of evidence shows that this is an undercount.

Whenever U.S. cities have tested a subset of the general population, such as homeless people or pregnant women, they have found at least some infected people who aren’t showing symptoms. And, as ProPublica first reported, there has been a spike in the number of Americans dying at home across the country. Those people may die of COVID-19 without ever entering the medical system, meaning that they never get tested.

There is clearly some group of Americans who have the coronavirus but who don’t show up in official figures. Now, using a statistic that has just become reliable, we can estimate the size of that group—and peek at the rest of the iceberg.

According to the Tracking Project’s figures, nearly one in five people who get tested for the coronavirus in the United States is found to have it. In other words, the country has what is called a “test-positivity rate” of nearly 20 percent.

That is “very high,” Jason Andrews, an infectious-disease professor at Stanford, told us. Such a high test-positivity rate almost certainly means that the U.S. is not testing everyone who has been infected with the pathogen, because it implies that doctors are testing only people with a very high probability of having the infection. People with milder symptoms, to say nothing of those with none at all, are going undercounted. Countries that test broadly should encounter far more people who are not infected than people who are, so their test-positivity rate should be lower.

The positivity rate is not the same as the proportion of COVID-19 cases in the American population at large, a metric called “prevalence.”* Nobody knows the true number of Americans who have been exposed to or infected with the coronavirus, though attempts to produce much sharper estimates of that figure through blood testing are under way. Prevalence is a crucial number for epidemiologists, in part because it lets them calculate a pathogen’s true infection-fatality rate: the number of people who die after becoming infected.

But the positivity rate is still valuable. “It’s not a normal metric, but it can be a very useful one in some circumstances,” Andrews said. The test-positivity rate is often used to track the spread of rare but deadly diseases, such as malaria, in places where most people aren’t able to get tested, he said. And if the same proportion of a population is being tested over time, the test-positivity rate can even be used to calculate the contagiousness of a disease.

Because the number of Americans tested for COVID-19 has changed over time, the U.S. test-positivity rate can’t yet provide much detailed information about the contagiousness or fatality rate of the disease. But the statistic can still give a rough sense of how bad a particular outbreak is by distinguishing between places undergoing very different sizes of epidemics, Andrews said. A country with a 25 percent positivity rate and one with a 2 percent positivity rate are facing “vastly different epidemics,” he said, and the 2 percent country is better off.

In that light, America’s 20 percent positivity rate is disquieting. The U.S. did almost 25 times as many tests on April 15 as on March 15, yet both the daily positive rate and the overall positive rate went up in that month. If the U.S. were a jar of 330 million jelly beans, then over the course of the outbreak, the health-care system has reached in with a bigger and bigger scoop. But every day, 20 percent of the beans it pulls out are positive for COVID-19. If the outbreak were indeed under control, then we would expect more testing—that is, a larger scoop—to yield a smaller and smaller proportion of positives. So far, that hasn’t happened.

In an ideal testing regime—and in any of the testing regimes that experts say must exist before the United States can end its lockdowns—anyone with a fever and a dry cough would be tested immediately. A very large portion, if not most, of those people would turn out not to be infected with the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, because humans are susceptible to many other respiratory infections. But when tests are rationed so strictly, only people with severe symptoms make it into the testing pool, ensuring that the positivity rate will be extremely high.

Local rationing rules are not the only reason that Americans are not getting tested. Some people live in a place that’s not doing much testing at all, either because doctors’ offices have no tests to offer or because of an already strained or nonexistent local health-care system. Others avoid the doctor if they’re sick, or never get sick enough to seek a test—but if the U.S. were testing more people, as experts say it must, then general-population surveillance or workplace testing could detect their illness, too.

The test-positivity rate, then, is a decent (if unusual) proxy for the severity of an outbreak in an area. And it shows clearly that the U.S. still lags far behind other countries in the course of fighting its outbreak. South Korea—which discovered its first coronavirus case on the same day as the U.S.—has tested more than half a million people, or about 1 percent of its population, and discovered about 10,500 cases. The U.S. has now tested 3.2 million people, which is also about 1 percent of its population, but it has found more than 630,000 cases. So while the U.S. has a 20 percent positivity rate, South Korea’s is only about 2 percent—a full order of magnitude smaller.

South Korea is not alone in bringing its positivity rate down: America’s figure dwarfs that of almost every other developed country. Canada, Germany and Denmark have positivity rates from 6 to 8 percent. Australia and New Zealand have 2 percent positivity rates. Even Italy—which faced one of the world’s most ravaging outbreaks—has a 15 percent rate. It has found nearly 160,000 cases and conducted more than a million tests. Virtually the only wealthy country with a larger positivity rate than the U.S. is the United Kingdom, where more than 30 percent of people tested for the virus have been positive.

Comparing American states to regions in other countries results in the same general pattern. In Lombardy, the hardest hit part of Italy, the positive rate today stands at about 28 percent. That’s comparable to the rate in Connecticut. But New York, so far the hardest hit state in the U.S., has an even higher rate of 41 percent. And in New Jersey, an astounding one in two people tested for the virus are found to have it.

The prevalence of COVID-19 might be higher in the New York area than anywhere else in the country, but high test-positivity rates are not confined to the mid-Atlantic. Five other states have a positive rate above 20 percent: Michigan, Georgia, Massachusetts, Illinois, and Colorado. They are spread across the country, and they all have obviously serious outbreaks. Each of the eight states with positive rates over 20 percent has, individually, reported more COVID-19 deaths than South Korea.

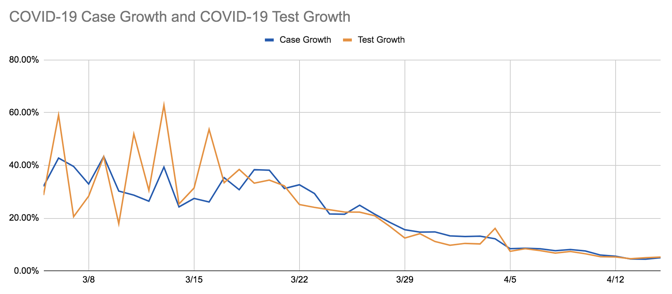

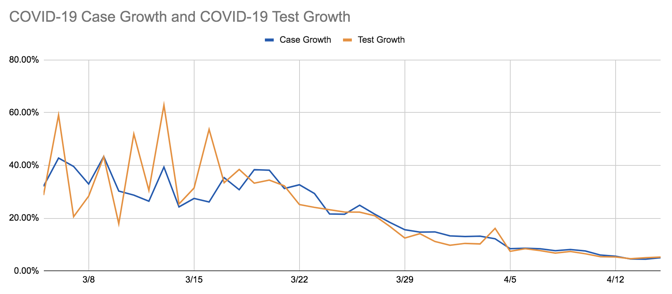

Hawaii, meanwhile, has tested twice as many people per capita as Illinois, but its positivity rate is only one-tenth as high as the larger state’s. As the outbreak comes under control, more states should have positivity rates closer to Hawaii’s, Andrews, the Stanford professor, said. At the beginning of a pandemic, both the actual number of infections and the number of tests per day shoot up, and the positivity rate is controlled by whichever happens to grow faster, he said. In this case, the faster-growing number appears to have been infections. “As things stabilize, if the testing rate declines and the positivity rate declines, you have some good signal that the epidemic is declining,” he said.

Not every epidemiologist feels as comfortable drawing conclusions from the test-positivity rate as Andrews. “If you want to interpret [the positivity rate] as a hint to prevalence in a particular location, you have to assume lots of other things stay constant,” Daniel Westreich, an epidemiology professor at the University of North Carolina, told us. He warned that too little was still known about who exactly is getting tested, and how reliable the tests are, to draw large conclusions from the positivity rate alone.

“We just haven’t tested enough people yet,” he said. “If you were doing random screening of the whole population, we just don’t know what you’d see. We don’t know how many asymptomatic viral shedders are out there.” As such, he advised extreme caution in using the rate—but being cautious about data, he added, “is my job.”

We feel confident reporting the U.S. test-positivity rate now for several reasons. First, we know that when states and cities ration tests, they do so by imposing criteria that allow for only the sickest or the most vulnerable people, such as residents of nursing homes, to get tested. We know that in states with a very high test-positivity rate, such as New Jersey, many people are still dying in nursing homes without getting tested. And we know that, even though a wide variety of nose-swab tests are being used across the country, the type of test used—called a polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, test—is generally very reliable. Westreich and Andrews said that any PCR test was “pretty good” at detecting true negatives.

Finally, the test-positivity rate has become much more reliable nationwide over the past few weeks. As recently as the end of March, not all states reported every negative test result from commercial laboratories. Nearly every state now publishes those numbers.

While our numbers still probably do not capture every coronavirus test in the U.S., outside evidence now suggests that our data are fairly complete. When the White House Coronavirus Task Force has reported the number of tests completed nationwide, its numbers have broadly matched the COVID Tracking Project’s. In addition, the largest commercial-test processors, Quest and LabCorp, have released top-line statistics that align with ours at the COVID Tracking Project.

The high positivity rate also suggests that new cases in the U.S. have plateaued only because the country has hit a ceiling in its testing capacity. Looking solely at positives, the U.S. is steaming toward 650,000 confirmed cases, but the number of new cases per day appears to be plateauing or even declining.

There are several ways to interpret this development. It might suggest, for instance, that the more than 3.2 million tests completed in the U.S. over the past two months have finally captured a good chunk of the people who are actually infected. While it’s clear that the country is not capturing every case, this decline in new positive cases might suggest the country has started to get the virus’s spread under control.

But there is another way to interpret the decline in new cases: The growth in the number of new tests completed per day has also plateaued. Since April 1, the country has tested roughly 145,000 people every day with no steady upward trajectory. The growth in the number of new cases per day, and the growth in the number of new tests per day, are very tightly correlated.

This tight correlation suggests that if the United States were testing more people, we would probably still be seeing an increase in the number of COVID-19 cases. And combined with the high test-positivity rate, it suggests that the reservoir of unknown, uncounted cases of COVID-19 across the country is still very large.

Each of those uncounted cases is a small tragedy and a microcosm of all the ways the U.S. testing infrastructure is still failing. When Sarah Pavis, a 36-year-old engineer in New York, woke up on Tuesday, she was out of breath and her heart was racing. An hour of deep breathing failed to calm her pulse. When her extremities started tingling, she called 911. It was her ninth day of COVID-19 symptoms.

New York City’s positivity rate is an astonishing 55 percent. More than 111,000 of the city’s residents have lab-confirmed cases of COVID-19, but Pavis is not among them. When the ambulance arrived at Pavis’s apartment, an EMS worker took her vitals, then explained there was little he could do to help. The city’s hospitals only admitted people with a blood-oxygen level of 94 percent or lower, he said. Pavis’s blood-oxygen reading was 96 percent. That 2 percent difference meant that her illness was not serious enough to merit hospitalization, not serious enough to be tested, not serious enough to be counted.