Category Archives: Out of Pocket Expenses

First ten drugs selected for Medicare’s drug price negotiation program

https://mailchi.mp/d0e838f6648b/the-weekly-gist-september-8-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

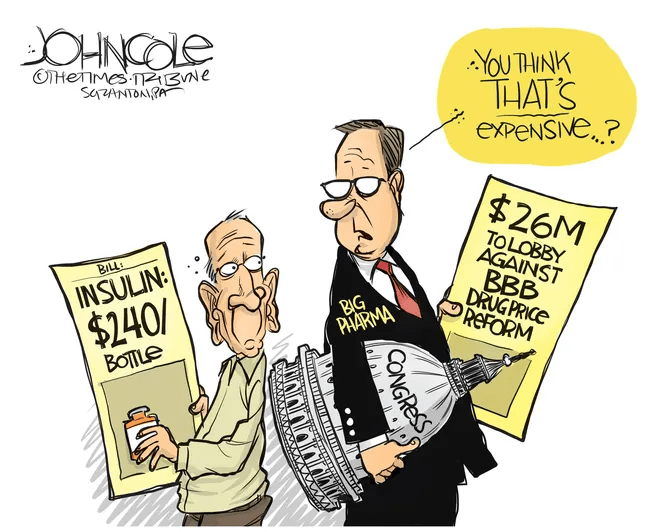

Last week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released the list of the first round of prescription drugs chosen for Medicare Part D price negotiations. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) granted CMS the authority to negotiate directly with pharmaceutical manufacturers, establishing a process that will ramp up to include 20 drugs per year and cover Part B medicines by 2029.

The majority of the initial 10 medications, including Eliquis, Jardiance, and Xarelto, are highly utilized across Medicare beneficiaries, treating mainly diabetes and cardiovascular disease. But three of the drugs (Enbrel, Imbruvica, and Stelara) are very high-cost drugs used by fewer than 50k beneficiaries to treat some cancers and autoimmune diseases.

Together the 10 drugs cost Medicare about $50B annually, comprising 20 percent of Part D spending. Drug manufacturers must now engage with CMS in a complex negotiation process, with negotiated prices scheduled to go into effect in 2026.

The Gist:

Most of the drugs on this list are not a surprise, with the Biden administration prioritizing more common chronic disease medications, with large total spend for the program, over the most expensive drugs, many of which are exempted by the IRA’s minimum seven-year grace period for new pharmaceuticals.

However, pharmaceutical companies are threatening to derail the process before it even begins. Several companies with drugs on the list have already filed lawsuits against the government on the grounds that the entire negotiation program is unconstitutional.

While President Biden is already touting lowering drug prices as a key plank of his reelection pitch, it will take years before these negotiations translate into lower costs for beneficiaries and reduced government spending. There also may be adverse unintended consequences, as drug companies may raise prices for commercial payers while increasing rebates to stabilize net prices, leading to higher costs for some consumers.

Still, it’s a step in the right direction for the US, given that we pay 2.4 times more than peer countries for prescription medications.

The Medicare Drug Pricing Program will Attract Uncomfortable Attention to the Rest of the Industry

Last Tuesday, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced the first 10 medicines that will be subject to price negotiations with Medicare starting in 2026 per authorization in the Inflation Reduction Act (2022). It’s a big deal but far from a done deal.

Here are the 10:

- Eliquis, for preventing strokes and blood clots, from Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer

- Jardiance, for Type 2 diabetes and heart failure, from Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly

- Xarelto, for preventing strokes and blood clots, from Johnson & Johnson

- Januvia, for Type 2 diabetes, from Merck

- Farxiga, for chronic kidney disease, from AstraZeneca

- Entresto, for heart failure, from Novartis

- Enbrel, for arthritis and other autoimmune conditions, from Amgen

- Imbruvica, for blood cancers, from AbbVie and Johnson & Johnson

- Stelara, for Crohn’s disease, from Johnson & Johnson

- Fiasp and NovoLog insulin products, for diabetes, from Novo Nordisk

Notably, they include products from 10 of the biggest drug manufacturers that operate in the U.S. including 4 headquartered here (Johnson and Johnson, Merck, Lilly, Amgen) and the list covers a wide range of medical conditions that benefit from daily medications.

But only one cancer medicine was included (Johnson & Johnson and AbbVie’s Imbruvica for lymphoma) leaving cancer drugs alongside therapeutics for weight loss, Crohn’s and others to prepare for listing in 2027 or later.

And CMS included long-acting insulins in the inaugural list naming six products manufactured by the Danish pharmaceutical giant Novo Nordisk while leaving the competing products made by J&J and others off. So, there were surprises.

To date, 8 lawsuits have been filed against the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services by drug manufacturers and the likelihood litigation will end up in the Supreme Court is high.

These cases are being brought because drug manufacturers believe government-imposed price controls are illegal. The arguments will be closely watched because they hit at a more fundamental question:

what’s the role of the federal government in making healthcare in the U.S. more affordable to more people?

Every major sector in healthcare– hospitals, health insurers, medical device manufacturers, physician organizations, information technology companies, consultancies, advisors et al may be impacted as the $4.6 trillion industry is scrutinized more closely . All depend on its regulatory complexity to keep prices high, outsiders out and growth predictable. The pharmaceutical industry just happens to be its most visible.

The Pharmaceutical Industry

The facts are these:

- 66% of American’s take one or more prescriptions: There were 4.73 billion prescriptions dispensed in the U.S. in 2022

- Americans spent $633.5 billion on their medicines in 2022 and will spend $605-$635 billion in 2025.

- This year (2023), the U.S. pharmaceutical market will account for 43.7% of the global pharmaceutical market and more than 70% of the industry’s profits.

- 41% of Americans say they have a fair amount or a great deal of trust in pharmaceutical companies to look out for their best interests and 83% favor allowing Medicare to negotiate pricing directly with drug manufacturers (the same as Veteran’s Health does).

- There were 1,106 COVID-19 vaccines and drugs in development as of March 18, 2023.

- The U.S. industry employs 811,000 directly and 3.2 million indirectly including the 325,000 pharmacists who earn an average of $129,000/year and 447,000 pharm techs who earn $38,000.

- And, in the U.S., drug companies spent $100 billion last year for R&D.

It’s a big, high-profile industry that claims 7 of the Top 10 highest paid CEOs in healthcare in its ranks, a persistent presence in social media and paid advertising for its brands and inexplicably strong influence in politics and physician treatment decisions.

The industry is not well liked by consumers, regulators and trading partners but uses every legal lever including patents, couponing, PBM distortion, pay-to-delay tactics, biosimilar roadblocks et al to protect its shareholders’ interests. And it has been effective for its members and advisors.

My take:

It’s easy to pile-on to criticism of the industry’s opaque pricing, lack of operational transparency, inadequate capture of drug efficacy and effectiveness data and impotent punishment against its bad actors and their enablers.

It’s clear U.S. pharma consumers fund the majority of the global industry’s profits while the rest of the world benefits.

And it’s obvious U.S. consumers think it appropriate for the federal government to step in. The tricky part is not just government-imposed price controls for a handful of drugs; it’s how far the federal government should play in other sectors prone to neglect of affordability and equitable access.

There will be lessons learned as this Inflation Reduction Act program is enacted alongside others in the bill– insulin price caps at $35/month per covered prescription, access to adult vaccines without cost-sharing, a yearly cap ($2,000 in 2025) on out-of-pocket prescription drug costs in Medicare and expansion of the low-income subsidy program under Medicare Part D to 150% of the federal poverty level starting in 2024. And since implementation of these price caps isn’t until 2026, plenty of time for all parties to negotiate, spin and adapt.

But the bigger impact of this program will be in other sectors where pricing is opaque, the public’s suspicious and valid and reliable data is readily available to challenge widely-accepted but flawed assertions about quality, value, access and outcomes. It’s highly likely hospitals will be next.

Stay tuned.

Is Affordability taken Seriously in US Healthcare?

It’s a legitimate question.

Studies show healthcare affordability is an issue to voters as medical debt soars (KFF) and public disaffection for the “medical system” (per Gallup, Pew) plummets. But does it really matter to the hospitals, insurers, physicians, drug and device manufacturers and army of advisors and trade groups that control the health system?

Each sector talks about affordability blaming inflation, growing demand, oppressive regulation and each other for higher costs and unwanted attention to the issue.

Each play their victim cards in well-orchestrated ad campaigns targeted to state and federal lawmakers whose votes they hope to buy.

Each considers aggregate health spending—projected to increase at 5.4%/year through 2031 vs. 4.6% GDP growth—a value relative to the health and wellbeing of the population. And each thinks its strategies to address affordability are adequate and the public’s concern understandable but ill-informed.

As the House reconvenes this week joining the Senate in negotiating a resolution to the potential federal budget default October 1, the question facing national and state lawmakers is simple: is the juice worth the squeeze?

Is the US health system deserving of its significance as the fastest-growing component of the total US economy (18.3% of total GDP today projected to be 19.6% in 2031), its largest private sector employer and mainstay for private investors?

Does it deserve the legal concessions made to its incumbents vis a vis patent approvals, tax exemptions for hospitals and employers, authorized monopolies and oligopolies that enable its strongest to survive and weaker to disappear?

Does it merit its oversized role, given competing priorities emerging in our society—AI and technology, climate changes, income, public health erosion, education system failure, racial inequity, crime and global tension with China, Russia and others.

In the last 2 weeks, influential Republicans leaders (Burgess, Cassidy) announced plans to tackle health costs and the role AI will play in the future of the system. Last Tuesday, CMS announced its latest pilot program to tackle spending: the States Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development Model (AHEAD Model) is a total cost of care budgeting program to roll out in 8 states starting in 2026. The Presidential campaigns are voicing frustration with the system and the spotlight on its business practices intensifying.

So, is affordability to the federal government likely to get more attention?

Yes. Is affordability on state radars as legislatures juggle funding for Medicaid, public health and other programs?

Yes, but on a program by program, non-system basis.

Is affordability front and center in CMS value agenda including the new models like its AHEAD model announced last week? Not really.

CMS has focused more on pushing hospitals and physicians to participate than engaging consumers. Is affordability for those most threatened—low and middle income households with high deductible insurance, the uninsured and under-insured, those with an expensive medical condition—front of mind? Every minute of every day.

Per CMS, out-of-pocket spending increased 4.3% in 2022 (down from 10.4% in 2021) and “is expected to accelerate to 5.2%, in part related to faster health care price growth. During 2025–31, average out-of-pocket spending growth is projected to be 4.1% per year.” But these data are misleading. It’s dramatically higher for certain populations and even those with attractive employer-sponsored health benefits worry about unexpected household medical bills.

So, affordability is a tricky issue that’s front of mind to 40% of the population today and more tomorrow.

Legislation that limits surprise medical bills, requires drug, hospital and insurer price transparency, expands scope of practice opportunities for mid-level professionals, avails consumers of telehealth services, restricts aggressive patient debt collection policies and others has done little to assuage affordability issues for consumers.

Ditto CMS’ value agenda which is more about reducing Medicare spending through shared savings programs with hospitals and physicians than improving affordability for consumers. That’s why outsiders like Walmart, Best Buy and others see opportunity: they think patients (aka members, enrollees, end users) deserve affordability solutions more than lip service.

Affordability to consumers is the most formidable challenge facing the US healthcare industry–more than burnout, operating margins, reimbursement or alternative payment models. Today, it is not taken seriously by insiders. If it was, evidence would be readily available and compelling. But it’s not.

Not for Profit Hospitals: Are they the Problem?

Last Monday, four U.S. Senators took aim at the tax exemption enjoyed by not-for-profit (NFP) hospitals in a letter to the IRS demanding detailed accounting for community benefits and increased agency oversight of NFP hospitals that fall short.

Last Tuesday, the Elevance Health Policy Institute released a study concluding that the consolidation of hospitals into multi-hospital systems (for-profit/not-for-profit) results in higher prices without commensurate improvement in patient care quality. “

Friday, Kaiser Health News Editor in Chief Elizabeth Rosenthal took aim at Ballad Health which operates in TN and VA “…which has generously contributed to performing arts and athletic centers as well as school bands. But…skimped on health care — closing intensive care units and reducing the number of nurses per ward — and demanded higher prices from insurers and patients.”

And also last week, the Pharmaceuticals’ Manufacturers Association released its annual study of hospital mark-ups for the top 20 prescription drugs used on hospitals asserting a direct connection between hospital mark-ups (which ranged from 234% to 724%) and increasing medical debt hitting households.

(Excerpts from these are included in the “Quotables” section that follows).

It was not a good week for hospitals, especially not-for-profit hospitals.

In reality, the storm cloud that has gathered over not-for-profit health hospitals in recent months has been buoyed in large measure by well-funded critiques by Arnold Ventures, Lown Institute, West Health, Patient Rights Advocate and others. Providence, Ascension, Bon Secours and now Ballad have been criticized for inadequate community benefits, excessive CEO compensation, aggressive patient debt collection policies and price gauging attributed to hospital consolidation.

This cloud has drawn attention from lawmakers: in NC, the State Treasurer Dale Folwell has called out the state’s 8 major NFP systems for inadequate community benefit and excess CEO compensation.

In Indiana, State Senator Travis Holdman is accusing the state’s NFP hospitals of “hoarding cash” and threatening that “if not-for-profit hospitals aren’t willing to use their tax-exempt status for the benefit of our communities, public policy on this matter can always be changed.” And now an influential quartet of U.S. Senators is pledging action to complement with anti-hospital consolidation efforts in the FTC leveraging its a team of 40 hospital deal investigators.

In response last week, the American Hospital Association called out health insurer consolidation as a major contributor to high prices and,

in a US News and World Report Op Ed August 8, challenged that “Health insurance should be a bridge to medical care, not a barrier.

Yet too many commercial health insurance policies often delay, disrupt and deny medically necessary care to patients,” noting that consumer medical debt is directly linked to insurer’ benefits that increase consumer exposure to out of pocket costs.

My take:

It’s clear that not-for-profit hospitals pose a unique target for detractors: they operate more than half of all U.S. hospitals and directly employ more than a third of U.S. physicians.

But ownership status (private not-for-profit, for-profit investor owned or government-owned) per se seems to matter less than the availability of facilities and services when they’re needed.

And the public’s opinion about the business of running hospitals is relatively uninformed beyond their anecdotal use experiences that shape their perceptions. Thus, claims by not-for-profit hospital officials that their finances are teetering on insolvency fall on deaf ears, especially in communities where cranes hover above their patient towers and their brands are ubiquitous.

Demand for hospital services is increasing and shifting, wage and supply costs (including prescription drugs) are soaring, and resources are limited for most.

The size, scale and CEO compensation for the biggest not-for-profit health systems pale in comparison to their counterparts in health insurance and prescription drug manufacturing or even the biggest investor-owned health system, HCA…but that’s not the point.

NFPs are being challenged to demonstrate they merit the tax-exempt treatment they enjoy unlike their investor-owned and public hospital competitors and that’s been a moving target.

In 2009, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) updated the Form 990 Schedule H to require more detailed reporting of community benefit expenditures across seven different categories including charity care, unreimbursed costs from means-tested government programs, community health spending, research, and others. The Affordable Care Act added requirements that non-profit hospitals complete community health needs assessments (CHNAs) every three years to identify the most pressing community health priorities and create detailed implementation strategies explaining how the identified needs will be addressed.

Thus, the methodology for consistently defining and accounting for community benefits needs attention. That would be a good start but alone it will not solve the more fundamental issue: what’s the future for the U.S. health system, what role do players including hospitals and others need to play, and how should it be structured and funded?

The issues facing the U.S. health industry are complex. The role hospitals will play is also uncertain. If, as polls indicate, the majority of Americans prefer a private health system that features competition, transparency, affordability and equitable access, the remedy will require input from every major healthcare sector including employers, public health, private capital and regulators alongside others.

It will require less from DC policy wonks and sanctimonious talking heads and more from frontline efforts and privately-backed innovators in communities, companies and in not-for-profit health systems that take community benefit seriously.

No sector owns the franchise for certainty about the future of U.S. healthcare nor its moral high ground. That includes not-for-profit hospitals.

The darkening cloud that hovers over not-for-profit health systems needs attention, but not alone, despite efforts to suggest otherwise.

Clarifying the community-benefit standard is a start, but not enough.

Are NFP hospitals a problem? Some are, most aren’t but all are impacted by the darkening cloud.

Latest court order pauses No Surprises Act’s Independent Dispute Resolution (IDR) process once again

https://mailchi.mp/27e58978fc54/the-weekly-gist-august-11-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

This week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for the second time suspended the arbitration process, outlined in the No Surprises Act, for new out-of-network payment disputes between providers and payers.

Federal judge Jeremy Kernodle in the Eastern District of Texas once again sided with the Texas Medical Association (TMA) in the lawsuit, which challenged CMS’s 2023 increase in administrative fees for arbitration (from $50 to $350), as well as restrictions on batching claims, which require providers to go through a separate IDR process for each claim related to an individual’s care episode. While CMS said that it made these changes to increase arbitration efficiency, TMA argued that the changes made the IDR process cost-prohibitive for providers, particularly smaller practices.

The Gist: Implementing the No Surprises Act has been a huge headache for CMS. Since it went into effect last spring, the IDR has seen a case load nearly 14 times greater than initially estimated, and has been hampered with delays. Insurers have blamed providers for overloading the system with frivolous claims, while providers have accused insurers of ignoring payment decisions determined by third-party arbiters or declining to pay in full.

The silver lining amid all this infighting is that the No Surprises Act is successfully preventing surprise bills for many consumers, despite the intra-industry turf war over its implementation.

Seniors’ medical debt soars to $54 billion in unpaid bills

Seniors face more than $50 billion in unpaid medical bills, many of which they shouldn’t have to pay, according to a federal watchdog report.

In an all-too-common scenario, medical providers charge elderly patients the full price of an expensive medical service rather than work with the insurer that is supposed to cover it. If the patient doesn’t pay, the provider sends the bill into collections, setting off a round of frightening letters, humiliating phone calls and damaging credit reports.

That is one conclusion of a recent report titled Medical Billing and Collections Among Older Americans, from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

The report recounts a horror story from a patient in southern Pennsylvania over a hospital visit, which should have been covered by insurance.

“I never received a bill from anyone,” the patient said in a 2022 complaint. Then came a phone call from a collection agency. “The woman on the phone started off aggressively screaming at me,” saying the patient owed $2,300.

“I told her there must be some mistake, that both Medicare and my supplement insurance would have covered it. It has in the past. She started screaming, very loud, ‘If you don’t pay me right now, I will put this on your credit report.’ I told her, ‘If you keep screaming at me, I will hang up.’ She continued, so I hung up.”

Nearly 4 million seniors reported unpaid medical bills in 2020, even though 98 percent of them had insurance, the report found. Medicare, the national health insurance program, was created to protect older Americans from burdensome medical expenses.

Total unpaid medical debt for seniors rose from $44.8 billion in 2019 to $53.8 billion in 2020, even though older adults reported fewer doctor visits and lower out-of-pocket costs in 2020.

Medical debt among seniors is rising partly because health care costs are going up, agency officials said. But much of the $53.8 billion is cumulative, they said, debt carried over from one year to the next. Figures for 2020 were the latest available.

Millions of older Americans are covered by both Medicare and Medicaid, a second federal insurance program for people of limited means. Federal and state laws widely prohibit health care providers from billing those patients for payment beyond nominal copays.

Yet, those low-income patients are more likely than wealthier seniors to report unpaid medical bills. The agency’s findings suggest that health care companies are billing low-income seniors “for amounts they don’t owe.” The findings draw from census data and consumer complaints collected between 2020 and 2022.

Many complaints depict medical providers and collection agencies relentlessly pursuing seniors for payment on bills that an insurance company has rejected over an error, rather than correcting the error and resubmitting the claim.

“Many of these errors likely are avoidable or fixable,” the report states, “but only a fraction of rejected claims are adjusted and resubmitted.”

When a patient points out the error, the creditors might agree to fix it, only to ignore that pledge and double down on the debt collection effort.

An Oklahoma senior recounted a collection agency nightmare that followed a hospital stay. After paying all legitimate bills, the patient discovered new charges from a collection agency on a credit report. In subsequent months, additional charges appeared.

The patient assembled billing statements and correspondence, hoping to clear the bogus charges. “I then proceeded to spend every weekday, all day, for two weeks on the phone, trying to find out who was billing me and why,” the patient said in a 2021 complaint.

The Oklahoman eventually paid the bills, “even though I don’t owe them.” Then, more charges appeared.

“Nice racket they have going,” the patient quipped.

As anyone with health insurance knows, medical providers occasionally charge patients for services that should have been covered by the insurer. Someone forgets to submit the claim, or types the wrong billing code or omits crucial documentation. Some providers charge patients more than the negotiated rate, a discounted fee set between the provider and insurer.

Americans spend hours of their lives disputing such charges. But many seniors aren’t up to the task.

“It’s tiring to have multiple conversations, sitting on the phone for an hour, chasing representatives,” said Genevieve Waterman, director of economic and financial security at the National Council on Aging.

“I think technology is outpacing older adults,” she said. “If you don’t have the digital literacy, you’re going to get lost.”

Older adults are more likely than younger people to have multiple chronic health conditions, which can require more detailed insurance documentation and face greater scrutiny, yielding more billing errors and denied claims, the federal report says.

Seniors are also more likely to rely on more than one insurance plan. As of 2020, two-thirds of older adults with unpaid medical bills had two or more sources of insurance.

Multiple insurers means a more complex billing process, making it harder for either patient or provider to file a claim and see that it is paid. With Medicaid, “you have 50 states, plus the territories,” said one official from the federal agency, speaking on condition of anonymity. “They each have their own billing system.”

In an analysis of Medicare complaints filed between 2020 and 2022, the agency found that 53 percent involved debt collectors seeking money the patient didn’t owe. In a smaller share of cases, patients reported that collection agents threatened punitive action or made false statements to press their case.

The complaints “illustrate how difficult it is to identify an inaccurate bill, learn where it originated, and correct other people’s mistakes,” the report states. “Some providers refuse to talk to consumers because the account has already been referred to collections. Even when providers seem willing to correct their own mistakes, debt collectors may continue attempting to collect a debt that is not owed and refuse to stop reporting inaccurate data.”

Rather than carry on a fight with collection agents over multiple rounds of calls and correspondence, many seniors become ensnared in a “doom loop,” the report says, convinced their appeal is hopeless. They pay the erroneous bill.

“I think some people get to the point where they just throw up their hands and give up a credit card number just to make the problem go away,” said Juliette Cubanski, deputy director of the Program on Medicare Policy at KFF.

Debt takes a toll on the mental and physical health of seniors, research has shown. Older adults with debt are more prone to a range of ailments, including hypertension, cancer and depression.

As the Oklahoma patient said, recalling a years-long battle over unpaid bills, “It nearly sent me back to the hospital.”