Healthcare is big business. That’s why JP Morgan Chase is hosting its 42nd Healthcare Conference in San Francisco starting today– the same week Congress reconvenes in DC with the business of healthcare on its agenda as well. The predispositions of the two toward the health industry could not be more different.

Context: the U.S. Health System in the Global Economy

Though the U.S. population is only 4% of the world total, our spending for healthcare products and services represents 45% of global healthcare market. Healthcare is 17.4% of U.S. GDP vs. an average of 9.6% for the economies in the 37 other high-income economies of the world. It is the U.S.’ biggest private employer (17.2 million) accounting for 24% of total U.S. job growth last year (BLS). And it’s a growth industry: annual health spending growth is forecast to exceed 4%/year for the foreseeable future and almost 5% globally—well above inflation and GDP growth. That’s why private investments in healthcare have averaged at least 15% of total private investing for 20+ years. That’s why the industry’s stability is central to the economy of the world.

The developed health systems of the world have much in common: each has three major sets of players:

- Service Providers: organizations/entities that provide hands-on services to individuals in need (hospitals, physicians, long-term care facilities, public health programs/facilities, alternative health providers, clinics, et al). In developed systems of the world, 50-60% of spending is in these sectors.

- Innovators: organizations/entities that develop products and services used by service providers to prevent/treat health problems: drug and device manufacturers, HIT, retail health, self-diagnostics, OTC products et al. In developed systems of the world, 20-30% is spend in these.

- Administrators, Watchdogs & Regulators: Organizations that influence and establish regulations, oversee funding and adjudicate relationships between service providers and innovators that operate in their systems: elected officials including Congress, regulators, government agencies, trade groups, think tanks et al. In the developed systems of the world, administration, which includes insurance, involves 5-10% of its spending (though it is close to 20% in the U.S. system due to the fragmentation of our insurance programs).

In the developed systems of the world, including the U.S., the role individual consumers play is secondary to the roles health professionals play in diagnosing and treating health problems. Governments (provincial/federal) play bigger roles in budgeting and funding their systems and consumer out-of-pocket spending as a percentage of total health spending is higher than the U.S. All developed and developing health systems of the world include similar sectors and all vary in how their governments regulate interactions between them. All fund their systems through a combination of taxes and out-of-pocket payments by consumers. All depend on private capital to fund innovators and some service providers. And all are heavily regulated.

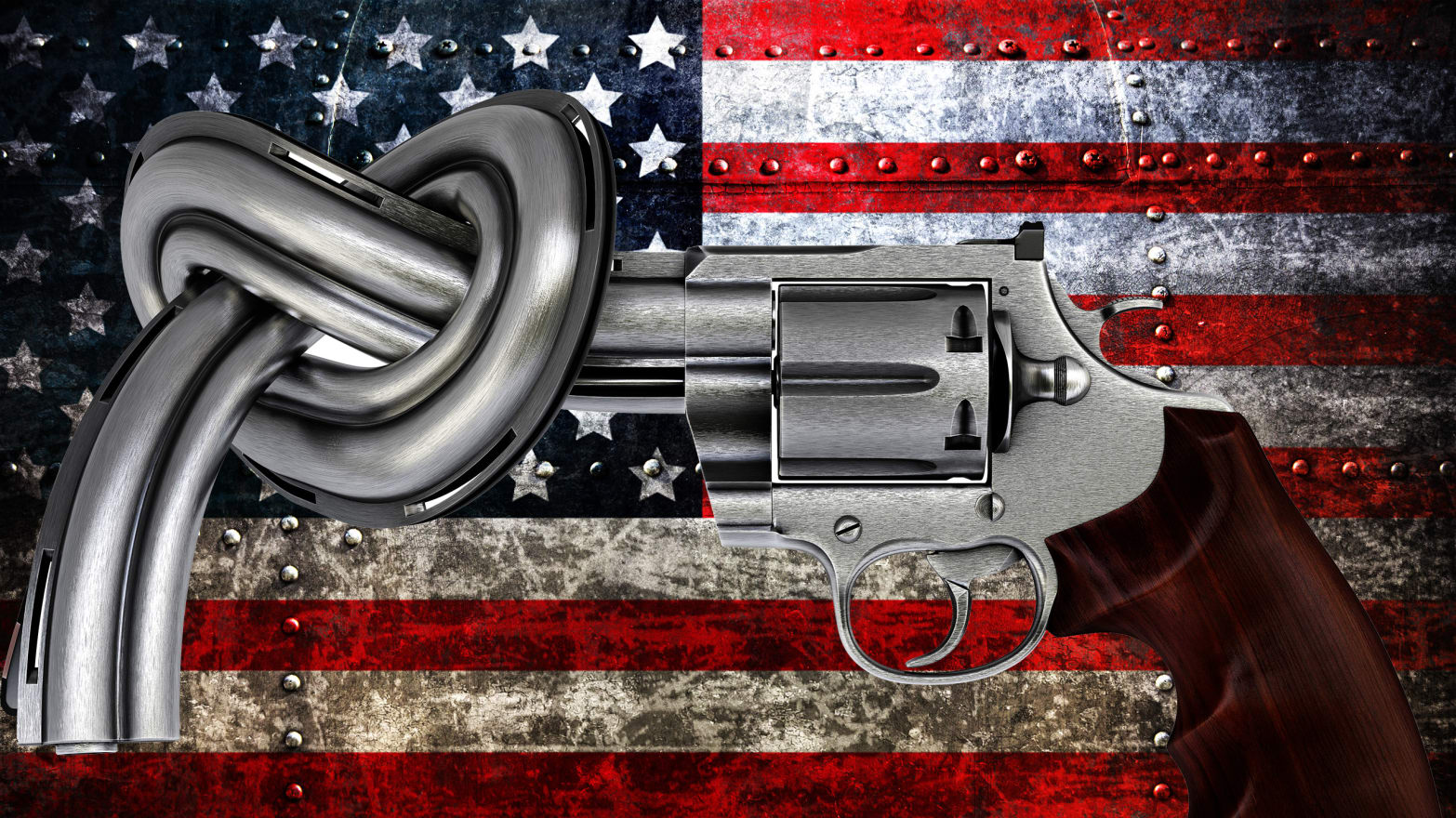

In essence, that makes the U.S. system unique are (1) the higher unit costs and prices for prescription drugs and specialty services, (2) higher administrative overhead costs, (3) higher prevalence of social health issues involving substance abuse, mental health, gun violence, obesity, et al (4) the lack of integration of our social services/public health and health delivery in communities and (5) lack of a central planning process linked to caps on spending, standardization of care based on evidence et al.

So, despite difference in structure and spending, developed systems of the world, like the U.S. look similar:

The Current Climate for the U.S. Health Industry

The global market for healthcare is attractive to investors and innovators; it is less attractive to most service providers since their business models are less scalable. Both innovator and service provider sectors require capital to expand and grow but their sources vary: innovators are primarily funded by private investors vs. service providers who depend more on public funding. Both are impacted by the monetary policies, laws and political realities in the markets where they operate and both are pivoting to post-pandemic new normalcy. But the outlook of investors in the current climate is dramatically different than the predisposition of the U.S. Congress toward healthcare:

- Healthcare innovators and their investors are cautiously optimistic about the future. The dramatic turnaround in the biotech market in 4Q last year coupled with investor enthusiasm for generative AI and weight loss drugs and lower interest rates for debt buoy optimism about prospects at home and abroad. The FDA approved 57 new drugs last year—the most since 2018. Big tech is partnering with established payers and providers to democratize science, enable self-care and increase therapeutic efficacy. That’s why innovators garner the lion’s share of attention at JPM. Their strategies are longer-term focused: affordability, generative AI, cost-reduction, alternative channels, self-care et al are central themes and the welcoming roles of disruptors hardwired in investment bets. That’s the JPM climate in San Franciso.

- By contrast, service providers, especially the hospital and long-term care sectors, are worried. In DC, Congress is focused on low-hanging fruit where bipartisan support is strongest and political risks lowest i.e.: price transparency, funding cuts, waste reduction, consumer protections, heightened scrutiny of fraud and (thru the FTC and DOJ) constraints on horizontal consolidation to protect competition. And Congress’ efforts to rein in private equity investments to protect consumer choice wins votes and worries investors. Thus, strategies in most service provider sectors are defensive and transactional; longer-term bets are dependent on partnerships with private equity and corporate partners. That’s the crowd trying to change Congress’ mind about cuts and constraints.

The big question facing JPM attendees this week and in Congress over the next few months is the same: is the U.S. healthcare system status quo sustainable given the needs in other areas at home and abroad?

Investors and organizations at JPM think the answer is no and are making bets with their money on “better, faster, cheaper” at home and abroad. Congress agrees, but the political risks associated with transformative changes at home are too many and too complex for their majority.

For healthcare investors and operators, the distance between San Fran and DC is further and more treacherous than the 2808 miles on the map.

The JPM crowd sees a global healthcare future that welcomes change and needs capital; Congress sees a domestic money pit that’s too dicey to handle head-on–two views that are wildly divergent.