The following, which originally appeared on the Drivers of Health blog, is authored by Luke Testa, Program Assistant, The Harvard Global Health Institute.

In 2018, a short video circulated on WhatsApp claiming that the MMR vaccine was designed by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to stop the population growth of Muslims. Subsequently, hundreds of madrassas across western Uttar Pradesh refused to allow health departments to vaccinate their constituents.

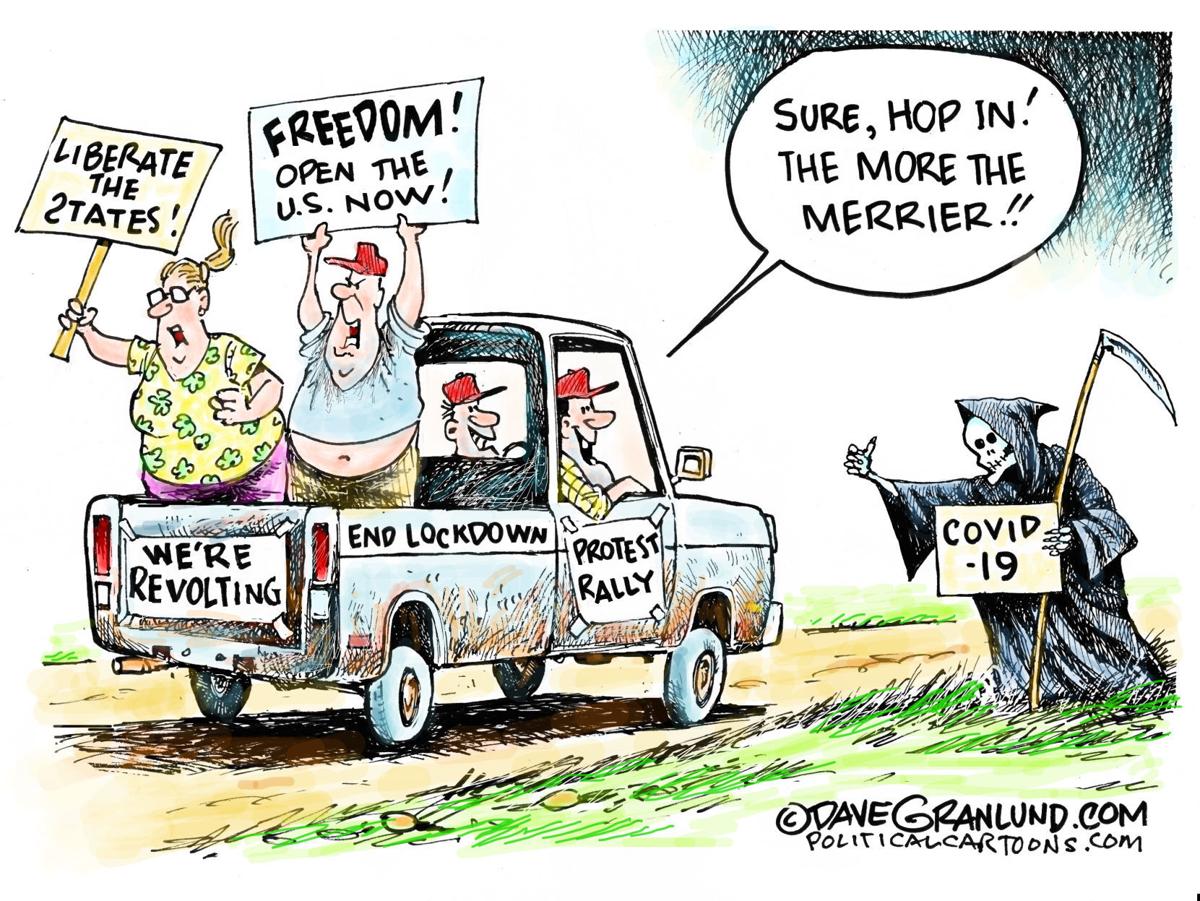

In 2020, a three-minute video claiming that the coronavirus vaccination campaign was secretly a plan by Bill Gates to implant trackable microchips in people was one of the most widely shared pieces of misinformation online. Alongside a torrent of online COVID-19 vaccine falsehoods and conspiracy theories, sources of medical mis- and disinformation are fostering distrust in COVID-19 vaccines, undermining immunization efforts, and demonstrating how poor information is a determinant of health.

Medical misinformation, referring to inaccurate or unverified information that can drive misperceptions about medical practices or treatments, has flooded the infosphere (all types of information available online). Examples can vary from overrepresentations of anecdotes claiming that complications occurred following inoculation to misinterpretations of research findings by well-meaning individuals.

Considering the many ways in which medical misinformation can shape health behaviors, researchers at the Oxford Internet Institute recently suggested that the infosphere should be classified as a social determinant of health (SDOH) (designated alongside general socioeconomic, environmental, and cultural conditions). This classification, they argue, properly accounts for the correlation between exposure to poor quality information and poor health outcomes.

The connection between information quality and health has been especially pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic. A 2021 study found that amongst those who indicated that they would definitely take a COVID-19 vaccine, exposure to misinformation induced a decline in intent of 6.2% in the U.K. and 6.4% in the U.S. Further, misinformation that appeared to be science-based was found to be especially damaging to vaccination intentions. These findings are particularly concerning considering the fact that during the pandemic, the 147 biggest anti-vaccine accounts on social media (which often purport to be science-based) gained 7.8 million followers in the first half of 2020, an increase of 19%.

During an unprecedented health crisis, medical misinformation within the infosphere is leaving both individuals and communities vulnerable to poor health outcomes. Those who are unvaccinated are at a higher risk of infection and increase the likelihood of community transmission. This places undue burden on those who cannot get vaccinated—due to inequities and/or preexisting conditions—and increases opportunities for variants to continue to mutate into more infectious and/or deadly forms of the virus. Poor quality information within the infosphere is undermining immunization efforts and threatens to prolong the ark of the pandemic.

Leveraging Healthcare Provider Influence in the Battle Against Poor Quality Information

Healthcare providers are uniquely suited to respond to this challenge. Throughout the pandemic, majorities of U.S. adults have identified their doctors and nurses as the most trustworthy sources of information about the coronavirus. In fact, 8 in 10 U.S. adults said that they are very or somewhat likely to turn to a doctor, nurse, or other healthcare provider when deciding whether or not to get a COVID-19 vaccine.

This influence is especially pertinent considering the state of vaccine resistance across the globe. In March 2021, a Kaiser Family Foundation poll found that 37% of U.S. respondents indicated some degree of resistance to vaccination. If that percentage of Americans remain unvaccinated, the country will be short of what is needed to achieve herd immunity (likely 70% or more vaccinated). Similar levels of resistance to vaccination remain high in countries across the globe, such as Lebanon, Serbia, Paraguay, and France.

Although medical misinformation is contributing to high rates of refusal, it is important to note that drivers of vaccine resistance are complex and intersectional. Vaccine distrust or refusal may be rooted in exposure to anti-vaccine rhetoric, racial injustice or medical exploitation in healthcare, fears that vaccine development was rushed, and/or other drivers. For this reason, responses must be tailored to unique individual or communal motivations. For example, experts have pressed the critical need for vaccine distrust within Black communities to be approached not as a shortcoming of community members, but as a failure of health systems to prove themselves as trustworthy.

With regard to resistance rooted in anti-COVID-19 vaccine misinformation, healthcare providers are leveraging their unique influence through novel, grassroots approaches to encourage vaccine uptake. In North Dakota, providers are recording videos and sending out messages to their patients communicating that they have been vaccinated and explaining why it is safe to do the same. On social media, a network of female doctors and scientists across various social media pages, such as Dear Pandemic (82,000 followers) and Your Local Epidemiologist (181,000 followers), are collaborating to answer medical questions, clear up misperceptions about COVID-19 vaccines, and provide communities with accurate information about the virus. Similarly, the #BetweenUsAboutUs online campaign is elevating conversations about vaccines with Black doctors, nurses, and researchers in an effort to increase vaccine confidence in BIPOC communities. This campaign is especially critical considering the fact that BIPOC communities are often the target of anti-vaccine groups in an effort to exploit existing, rational distrust in health systems.

In addition to these timely responses, evidence-based interventions offer promising opportunities for healthcare providers to improve vaccine uptake amongst their patients. For example, there is a growing consensus around the practice of motivational interviewing (MI).

MI is a set of patient-centered communication techniques that aim to enhance a patient’s intrinsic motivation to change health behaviors by tapping into their own arguments for change. The approach is based on empathetic, nonjudgmental patient-provider dialogue. In other words, as opposed to simply telling a patient why they should get vaccinated, a provider will include the patient in a problem-solving process that accounts for their unique motivations and helps them discover their own reasons for getting vaccinated.

When applying MI techniques to a conversation with a patient who is unsure if they should receive a vaccine, providers will use an “evoke-provide-evoke” approach where they will ask patients: 1) what they already know about the vaccine; 2) if the patient would like additional information about the vaccine (if yes, then provide the most up to date information); and 3) how the new information changes how they are thinking or feeling about vaccination. During these conversations, the MI framework encourages providers to ask open-ended questions, practice reflective listening, offer affirmations, elicit pros and cons of change, and summarize conversations, amongst other tools.

Numerous studies show motivational interviewing to be effective in increasing vaccine uptake. For example, one randomized controlled trial found that with parents in maternity wards, vaccine hesitancy fell by 40% after participation in an educational intervention based on MI. Given its demonstrated effectiveness, MI is likely to help reduce vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 pandemic.

With infectious disease outbreaks becoming more likely and resistance to various vaccines increasing across the globe, continuing to leverage healthcare providers’ unique influence through grassroots campaigns while honing motivational interviewing skills as a way to combat mis- and disinformation in the infosphere may prove critical to advancing public health now and in the future.

Share this…