Sure, they’re less expensive for consumers, but short-term health policies have another side: They’re highly profitable for insurers and offer hefty sales commissions.

Driven by rising premiums for Affordable Care Act plans, interest in short-term insurance is growing, boosted by Trump administration actions to ease Obama-era restrictions and possibly make federal subsidies available to consumers to purchase them.

That’s good news for brokers, who often see commissions on such policies hit 20 percent or more.

On a policy costing $200 a month, for example, that could translate to a $40 payment each month. By contrast, ACA plan commissions, which are often flat dollar amounts rather than a percentage of premium, can range from zero to $20 per enrollee per month.

“Customers are paying less and I’m making more,” said Cindy Holtzman, a broker in Woodstock, Ga., who said she gets 20 percent on short-term plan commissions.

Large online brokers also are eagerly eyeing the market.

Ehealth, one such firm, will “continue to shift our focus to selling short-term plans and non-ACA insurance packages,” CEO Scott Flanders told investors in October. The firm saw an 18 percent annual jump in enrollment in short-term plans this year, he added.

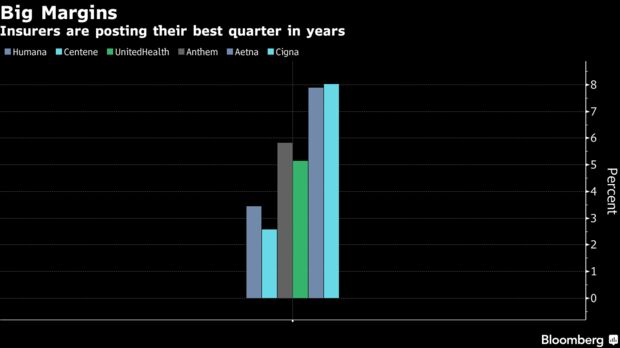

Insurers, too, see strong profits from plans because they generally pay out very little toward medical care when compared with the more comprehensive ACA plans.

Still, some agents like Holtzman have mixed feelings about selling the plans, because they offer skimpier coverage than ACA insurance. One 58-year-old client of Holtzman’s wanted one, but he had health problems. She also learned his income qualified him for an ACA subsidy, which currently cannot be used to purchase short-term coverage.

“There’s no way I would have considered a short-term plan for him,” she said. “I found him an ACA plan for $360 a month with a reduced deductible.” (A federal district court judge in Texas issued a ruling Dec. 14 striking down the ACA, which would among other things impact the requirements of ACA coverage and subsidies. The decision is expected to face appeal.)

Short-term plans can be far less expensive than ACA plans because they set annual or lifetime payment limits. Most exclude people with medical conditions, they often don’t cover prescription drugs, and policies exclude in fine print some conditions or treatments. Injuries sustained in school sports programs, for example, often are not covered. (These plans can be purchased at any time throughout the year, which is different than plans sold through the federal marketplaces. The open enrollment period for those ACA plans in most states ends Dec. 15.)

Consequently, insurers providing short-term plans don’t have to pay as many medical bills, so they have more money left over for profits. In forms filed with state regulators, Independence American Insurance Co. in Ohio shows it expects 60 percent of its premium revenue to be spent on its enrollees’ medical care. The remaining 40 percent can go to profits, executive salaries, marketing and commissions.

A 2016 report from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners showed that, on average, short-term plans paid out about 67 percent of their earnings on medical care.

That compares with ACA plans, which are required under the law to spend at least 80 percent of premium revenue on medical claims.

Short-term plans have long been sold mainly as a stopgap measure for people between jobs or school coverage. While exact figures are not available, brokers say interest dropped when the ACA took effect in 2014 because many people got subsidies to buy ACA plans and having a short-term plan did not exempt consumers from the law’s penalty for not carrying insurance.

But this year it ticked up again after Congress eliminated the penalty for 2019 coverage. At the same time, the premiums for ACA plans rose on average more than 30 percent.

“If I don’t want someone to walk out of the office with nothing at all because of cost, that’s when I will bring up short-term plans,” said Kelly Rector, president of Denny & Associates, an insurance sales brokerage in O’Fallon, a suburb of St. Louis. “But I don’t love the plans because of the risk.”

The Obama administration limited short-term plans to 90-day increments to reduce the number of younger or healthier people who would leave the ACA market. That rule, the Trump administration complained, forced people to reapply every few months and risk rejection by insurers if their health had declined.

This summer, the administration finalized new rules allowing insurers to offer short-term plans for up to 12 months — and gave them the option to allow renewals for up to three years. States can be more restrictive or even bar such plans altogether.

Administration officials estimate short-term plans could be half the cost of the more comprehensive ACA insurance and draw 600,000 people to enroll in 2019, with 100,000 to 200,000 of those dropping ACA coverage to do so.

And recent guidance to states says they could seek permission to allow federal subsidies to be used for short-term plans. Currently, those subsidies apply only to ACA-compliant plans.

Granting subsidies for short-term plans “would mean tax dollars are not only subsidizing commissions, but also executive salaries and marketing budgets,” said Sabrina Corlette of Georgetown University Center on Health Insurance Reforms.

No state has yet applied to do that.

For now, brokers are focusing on getting their clients into some kind of coverage for next year. Commissions on both ACA and short-term plans are getting their attention.

After several years of declining commissions for ACA plans — with some carriers cutting them altogether a couple of years ago — brokers say they are seeing a bit of a rebound.

Among Colorado ACA insurers, “it’s gone from about $14 to $16 per enrollee [a month] to $16 to $18,” said Louise Norris, a health policy writer and co-owner of an insurance brokerage.

Rector, in Missouri, said an insurer that last year paid no commissions has reinstated them for 2019 coverage. For her, that doesn’t really matter, she said, because once carriers started reducing or eliminating commissions, she began charging clients a flat rate to enroll.

Norris noted that some states changed their laws so brokers could do just that.

At least one state, Connecticut, ruled that insurers had to pay a commission, which she thinks is protective for consumers.

“Insurance regulators need to step in and make sure brokers are getting paid,” said Norris, or some brokers, “out of necessity,” might steer people to higher-commission products, such as short-term plans, that might not be the best answer for their clients.

Her agency does not sell short-term or some other types of limited-benefit plans.

“I don’t want to have a client come back and say I’ve had a heart attack and have all these unpaid bills,” she said.