http://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-biz-hospital-financial-struggles-20171215-story.html

he list reads like a who’s who of hospital systems in the Chicago area: Advocate Health Care, Edward-Elmhurst Health, Centegra Health System.

But it’s a list of hospitals systems that cut jobs this year to deal with financial pressures — not a list any hospital is eager to join.

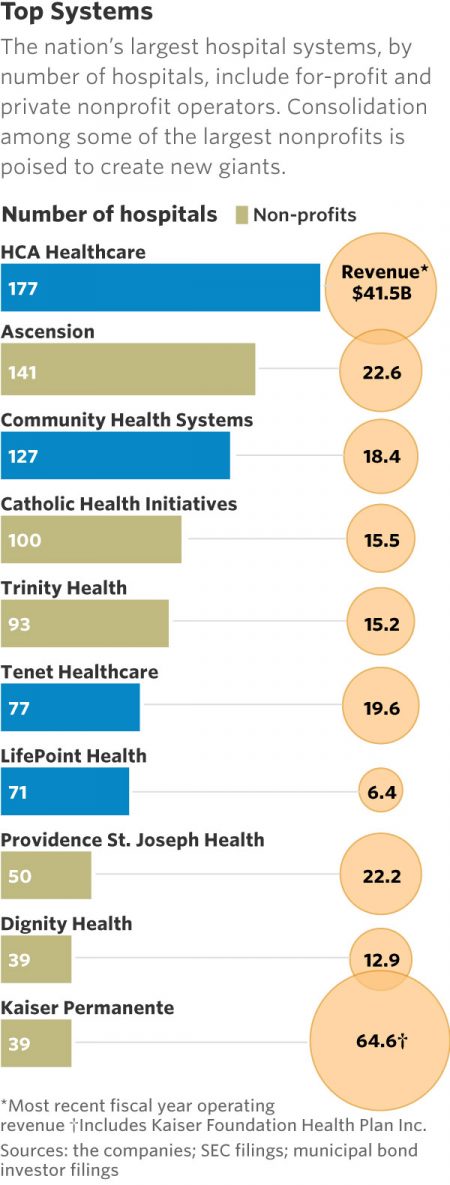

Hospitals in Illinois and across the country faced financial stresses this year and are likely to continue feeling the squeeze into 2018 and beyond, experts say. Those pressures could fuel more cuts, consolidation and changes to patient care and services.

“We have many hospitals doing their best just to survive,” said A.J. Wilhelmi, president and CEO of the Illinois Health and Hospital Association.

Moody’s Investors Service recently downgraded its outlook for not-for-profit health care and public health care nationally from stable to negative, with the expectation that operating cash flow will fall by 2 percent to 4 percent over the next 12-18 months. About three-fourths of Illinois hospitals are not-for-profit.

“(For) almost every hospital and health system we talk to, (financial pressure) is at the top of their list in terms of ongoing issues,” said Michael Evangelides, a principal at Deloitte Consulting.

A number of factors are to blame.

Leaders of Illinois systems say reimbursements from government insurance programs, such as Medicaid and Medicare, don’t cover the full cost of care. And with baby boomers growing older, many hospitals’ Medicare populations are on the rise. It doesn’t help that payments to hospitals from the state were delayed amid Illinois’ recently resolved, two-year budget impasse, Wilhelmi said.

Unpaid medical bills, known as bad debt, are also increasing as more patients find themselves responsible for large deductibles. Payments from private insurers are no longer helping hospitals as much as they once did. Though those payments tend to be higher than reimbursements from Medicare and Medicaid, they’re not growing as fast as they used to, said Daniel Steingart, a vice president at Moody’s.

Growing expenses, such as for drugs and information technology services, also are driving hospitals’ financial woes. And hospitals are spending vast sums on electronic medical record systems and cybersecurity, Steingart said.

Many also expect that the new federal tax bill, passed Wednesday, may further strain hospital budgets in the future. That bill will do away with the penalty for not having health insurance, starting in 2019. Hospital leaders worry that change will lead to more uninsured people who have trouble paying hospital bills and wait until their conditions become dire and complex before seeking care.

With so much going on, it can be tough for hospitals to meet revenue goals.

“You’re talking about a phenomenon taking place across the country,” said Advocate President and CEO Jim Skogsbergh. Advocate announced in May that it planned to make $200 million in cuts after failing to meet revenue targets. In March, Advocate walked away from a planned merger with NorthShore University HealthSystem after a federal judge sided with the Federal Trade Commission, which had challenged the deal. Advocate is now hoping to merge with Wisconsin health care giant Aurora Health Care, although the hospital systems say financial issues aren’t driving the deal.

“Everybody is seeing declining revenues, and margins are being squeezed. It’s a very challenging time,” Skogsbergh said.

Hospitals in Illinois have responded to the pressures in a number of ways, including with job reductions. Advocate laid off about 75 workers in the fall; Centegra announced plans in September to eliminate 131 jobs and outsource another 230; and Edward-Elmhurst laid off 84 employees, eliminating 234 positions in all, mostly by not filling vacant spots.

Hospitals also are changing some of the services they offer patients and delaying technology improvements, said the Illinois hospital association’s Wilhelmi.

Centegra Hospital-Woodstock earlier this year stopped admitting most overnight patients, one of a number of changes meant to save money and increase efficiency. As a result, the system “achieved our goal of keeping much-needed services in our community,” spokeswoman Michelle Green said in a statement.

Many Illinois hospitals have also cut inpatient pediatric services, citing weak demand, and are instead investing in outpatient services.

The challenge is saving money while improving care and patient outcomes, said Evangelides of Deloitte. Hospitals are striving to do both at the same time.

Advocate, for example, opened its AdvocateCare Center in 2016 on the city’s South Side to treat Medicare patients with multiple chronic illnesses and conditions. The clinic offers doctors, pharmacists, physical therapists, social workers and exercise psychologists. It has helped reduce hospital admissions and visits among its patients, said Dr. Lee Sacks, Advocate executive vice president and chief medical officer.

Advocate didn’t open the clinic primarily to help its bottom line. The goal was to improve patient care while also potentially reducing some costs.

But such moves are becoming increasingly important to hospitals.

“It really does impact everyone,” Evangelides said of the financial pressures facing hospitals. “We all have a giant stake in helping and hoping that the systems across the country … can ultimately survive and thrive.”