Fewer Uninsured Americans and Shorter Coverage Gaps, But More Underinsured

What does health insurance coverage look like for Americans today, more than eight years after the Affordable Care Act’s passage? In this brief, we present findings from the Commonwealth Fund’s latest Biennial Health Insurance Survey to assess the extent and quality of coverage for U.S. working-age adults. Conducted since 2001, the survey uses three measures to gauge the adequacy of people’s coverage:

- whether or not they have insurance

- if they have insurance, whether they have experienced a gap in their coverage in the prior year

- whether high out-of-pocket health care costs and deductibles are causing them to be underinsured, despite having continuous coverage throughout the year.

As the findings highlighted below show, the greatest deterioration in the quality and comprehensiveness of coverage has occurred among people in employer plans. More than half of Americans under age 65 — about 158 million people — get their health insurance through an employer, while about one-quarter either have a plan purchased through the individual insurance market or are enrolled in Medicaid.1Although the ACA has expanded and improved coverage options for people without access to a job-based health plan, the law largely left the employer market alone.2

Survey Highlights

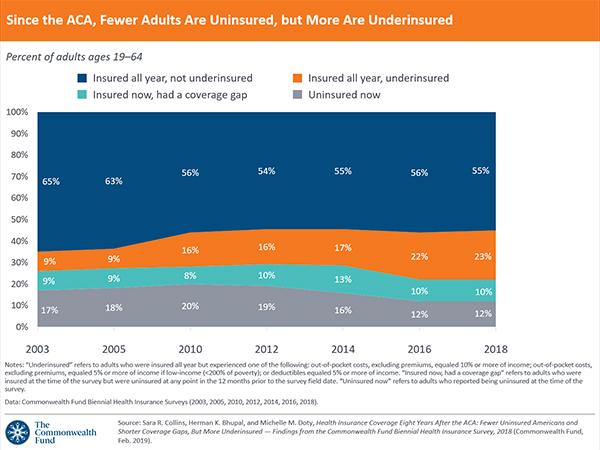

- Today, 45 percent of U.S. adults ages 19 to 64 are inadequately insured — nearly the same as in 2010 — though important shifts have taken place.

- Compared to 2010, many fewer adults are uninsured today, and the duration of coverage gaps people experience has shortened significantly.

- Despite actions by the Trump administration and Congress to weaken the ACA, the adult uninsured rate was 12.4 percent in 2018 in this survey, statistically unchanged from the last time we fielded the survey in 2016.

- More people who have coverage are underinsured now than in 2010, with the greatest increase occurring among those in employer plans.

- People who are underinsured or spend any time uninsured report cost-related problems getting care and difficulty paying medical bills at at higher rates than those with continuous, adequate coverage.

- Federal and state governments could enact policies to extend the ACA’s health coverage gains and improve the cost protection provided by individual-market and employer plans.

The 2018 Commonwealth Fund Biennial Heath Insurance Survey included a nationally representative sample of 4,225 adults ages 19 to 64. SSRS conducted the telephone survey between June 27 and November 11, 2018.3 (See “How We Conducted This Study” for more detail.)

WHO IS UNDERINSURED?

In this analysis, we use a measure of underinsurance that accounts for an insured adult’s reported out-of-pocket costs over the course of a year, not including insurance premiums, as well as his or her plan deductible. (The measure was first used in the Commonwealth Fund’s 2003 Biennial Health Insurance Survey.*) These actual expenditures and the potential risk of expenditures, as represented by the deductible, are then compared with household income. Specifically, we consider people who are insured all year to be underinsured if:

- their out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, over the prior 12 months are equal to 10 percent or more of household income; or

- their out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, over the prior 12 months are equal to 5 percent or more of household income for individuals living under 200 percent of the federal poverty level ($24,120 for an individual or $49,200 for a family of four); or

- their deductible constitutes 5 percent or more of household income.

The out-of-pocket cost component of the measure is only triggered if a person uses his or her plan to obtain health care. The deductible component provides an indicator of the financial protection the plan offers and the risk of incurring costs before someone gets health care. The definition does not include other dimensions of someone’s health plan that might leave them potentially exposed to costs, such as copayments or uncovered services. It therefore provides a conservative measure of underinsurance in the United States.

Compared to 2010, when the ACA became law, fewer people today are uninsured, but more people are underinsured. Of the 194 million U.S. adults ages 19 to 64 in 2018, an estimated 87 million, or 45 percent, were inadequately insured (see Tables 1 and 2).

Despite actions by the Trump administration and Congress to weaken the ACA, our survey found no statistically significant change in the adult uninsured rate by late 2018 compared to 2016 (Table 3). This finding is consistent with recent federal surveys, but other private surveys (including other Commonwealth Fund surveys) have found small increases in uninsured rates since 2016 (see “Changes in U.S. Uninsured Rates Since 2013”).

While there has been no change since 2010, statistically speaking, in the proportion of people who are insured now but have experienced a recent time without coverage, these reported gaps are of much shorter duration on average than they were before the ACA. In 2018, 61 percent of people who reported a coverage gap said it has lasted for six months or less, compared to 31 percent who said they had been uninsured for a year or longer. This is nearly a reverse of what it was like in 2012, two years before the ACA’s major coverage expansions. In that year, 57 percent of adults with a coverage gap reported it was for a year or longer, while one-third said it was a shorter gap.

There also has been some improvement in long-term uninsured rates. Among adults who were uninsured at the time of the survey, 54 percent reported they had been without coverage for more than two years, down from 72 percent before the ACA coverage expansions went into effect. The share of those who had been uninsured for six months or less climbed to 20 percent, nearly double the rate prior to the coverage expansions.

Of people who were insured continuously throughout 2018, an estimated 44 million were underinsured because of high out-of-pocket costs and deductibles (Table 1). This is up from an estimated 29 million in 2010 (data not shown). The most likely to be underinsured are people who buy plans on their own through the individual market including the marketplaces. However, the greatest growth in the number of underinsured adults is occurring among those in employer health plans.

WHY ARE INSURED AMERICANS SPENDING SO MUCH OF THEIR INCOME ON HEALTH CARE COSTS?

Several factors may be contributing to high underinsured rates among adults in individual market plans and rising rates in employer plans:

- Although the Affordable Care Act’s reforms to the individual market have provided consumers with greater protection against health care costs, many moderate-income Americans have not seen gains. The ACA’s essential health benefits package, cost-sharing reductions for lower- income families, and out-of-pocket cost limits have helped make health care more affordable for millions of Americans. But while the cost-sharing reductions have been particularly important in lowering deductibles and copayments for people with incomes under 250 percent of the poverty level (about $62,000 for a family of four), about half of people who purchase marketplace plans, and all of those buying plans directly from insurance companies, do not have them.4

- The bans against insurers excluding people from coverage because of a preexisting condition and rating based on health status have meant that individuals with greater health needs, and thus higher costs, are now able to get health insurance in the individual market. Not surprisingly, the survey data show that people with individual market coverage are somewhat more likely to have health problems than they were in 2010, which means they also have higher costs.

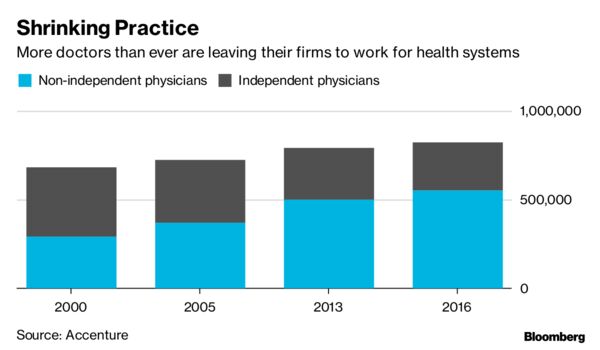

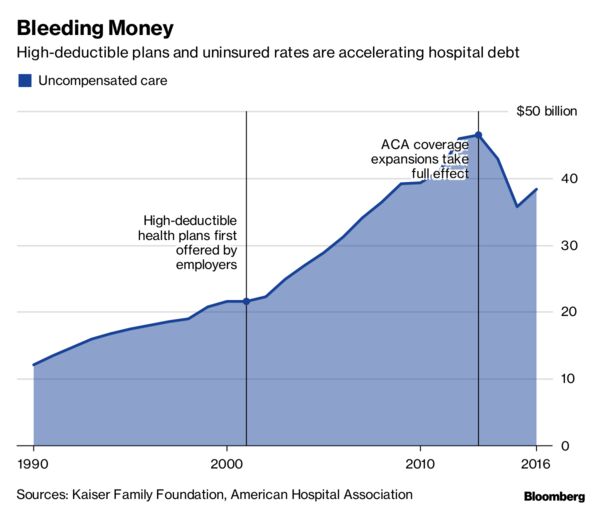

- While plans in the employer market historically have provided greater cost protection than plans in the individual market, businesses have tried to hold down premium growth by asking workers to shoulder an increasing share of health costs, particularly in the form of higher deductibles.5 While the ACA’s employer mandate imposed a minimum coverage requirement on large companies, the requirement amounts to just 60 percent of typical person’s overall costs. This leaves the potential for high plan deductibles and copayments.

- Growth in Americans’ incomes has not kept pace with growth in health care costs. Even when health costs rise more slowly, they can take an increasingly larger bite out of incomes.

It is well documented that people who gained coverage under the ACA’s expansions have better access to health care as a result.6 This has led to overall improvement in health care access, as indicated by multiple surveys.7 In 2014, the year the ACA’s major coverage expansions went into effect, the share of adults in our survey who said that cost prevented them from getting health care that they needed, such as prescription medication, dropped significantly (Table 4). But there has been no significant improvement since then.

The lack of continued improvement in overall access to care nationally reflects the fact that coverage gains have plateaued, and underinsured rates have climbed. People who experience any time uninsured are more likely than any other group to delay getting care because of cost (Table 5). And among people with coverage all year, those who were underinsured reported cost-related delays in getting care at nearly double the rate of those who were not underinsured.

There was modest but significant improvement following the ACA’s coverage expansions in the proportion of all U.S. adults who reported having difficulty paying their medical bills or said they were paying off medical debt over time (Table 4). Federal surveys have found similar improvements.8 However, those gains have stalled.

Inadequate insurance coverage leaves people exposed to high health care costs, and these expenses can quickly turn into medical debt. More than half of uninsured adults and insured adults who have had a coverage gap reported that they had had problems paying medical bills or were paying off medical debt over time (Table 6). Among people who had continuous insurance coverage, the rate of medical bill and debt problems is nearly twice as high for the underinsured as it is for people who are not underinsured.

Having continuous coverage makes a significant difference in whether people have a regular source of care, get timely preventive care, or receive recommended cancer screenings. Adults with coverage gaps or those who were uninsured when they responded to the survey were the least likely to have gotten preventive care and cancer screenings in the recommended time frame.

Being underinsured, however, does not seem to reduce the likelihood of having a usual source of care or receiving timely preventive care or cancer screens — provided a person has continuous coverage. This is likely because the ACA requires insurers and employers to cover recommended preventive care and cancer screens without cost-sharing. Even prior to the ACA, a majority of employer plans provided predeductible coverage of preventive services.9

Conclusion and Policy Implications

U.S. working-age adults are significantly more likely to have health insurance since the ACA became law in 2010. But the improvement in uninsured rates has stalled. In addition, more people have health plans that fail to adequately protect them from health care costs, with the fastest deterioration in cost protection occurring in the employer market. The ACA made only minor changes to employer plans, and the erosion in cost protection has taken a bite out of the progress made in Americans’ health coverage since the law’s enactment.

Both the federal government and the states, however, have the ability to extend the law’s coverage gains and improve the cost protection of both individual-market and employer plans. Here is a short list of policy options:

- Expand Medicaid without restrictions. The 2018 midterm elections moved as many as five states closer to joining the 32 states that, along with the District of Columbia, have expanded eligibility for Medicaid under the ACA.10 As many as 300,000 people may ultimately gain coverage as a result.11 But, encouraged by the Trump administration, several states are imposing work requirements on people eligible for Medicaid — a move that could reverse these coverage gains. So far, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has approved similar work-requirement waivers in seven states and is considering applications from at least seven more. Arkansas imposed a work requirement last June, and, to date, more than 18,000 adults have lost their insurance coverage as a result.

- Ban or place limits on short-term health plans and other insurance that doesn’t comply with the ACA. The Trump administration loosened regulations on short-term plans that don’t comply with the ACA, potentially leaving people who enroll in them exposed to high costs and insurance fraud. These plans also will draw healthier people out of the marketplaces, increasing premiums for those who remain and federal costs of premium subsidies. Twenty-three states have banned or placed limits on short-term insurance policies. Some lawmakers have proposed a federal ban.

- Reinsurance, either state or federal. The ACA’s reinsurance program was effective in lowering marketplace premiums. After it expired in 2017, several states implemented their own reinsurance programs.12 Alaska’s program reduced premiums by 20 percent in 2018. These lower costs particularly help people whose incomes are too high to qualify for ACA premium tax credits. More states are seeking federal approval to run programs in their states. Several congressional bills have proposed a federal reinsurance program.

- Reinstate outreach and navigator funding for the 2020 open-enrollment period. The administration has nearly eliminated funding for advertising and assistance to help people enroll in marketplace plans.13 Research has found that both activities are effective in increasing enrollment.14 Some lawmakers have proposed reinstatingthis funding.

- Lift the 400-percent-of-poverty cap on eligibility for marketplace tax credits. This action would help people with income exceeding $100,000 (for a family of four) better afford marketplace plans. The tax credits work by capping the amount people pay toward their premiums at 9.86 percent. Lifting the cap has a built in phase out: as income rises, fewer people qualify, since premiums consume an increasingly smaller share of incomes. RAND researchers estimate that this policy change would increase enrollment by 2 million and lower marketplace premiums by as much as 4 percent as healthier people enroll. It would cost the federal government an estimated $10 billion annually.15 Legislation has been introduced to lift the cap.

- Make premium contributions for individual market plans fully tax deductible. People who are self-employed are already allowed to do this.16

- Fix the so-called family coverage glitch. People with employer premium expenses that exceed 9.86 percent of their income are eligible for marketplace subsidies, which trigger a federal tax penalty for their employers. There’s a catch: this provision applies only to single-person policies, leaving many middle-income families caught in the “family coverage glitch.” Congress could lower many families’ premiums by pegging unaffordable coverage in employer plans to family policies instead of single policies.17

REDUCE COVERAGE GAPS

- Inform the public about their options. People who lose coverage during the year are eligible for special enrollment periods for ACA marketplace coverage. Those eligible for Medicaid can sign up at any time. But research indicates that many people who lose employer coverage do not use these options.18 The federal government, the states, and employers could increase awareness of insurance options outside the open-enrollment periods through advertising and education.

- Reduce churn in Medicaid. Research shows that over a two-year period, one-quarter of Medicaid beneficiaries leave the program and become uninsured.19 Many do so because of administrative barriers.20 By imposing work requirements, as some states are doing, this involuntary disenrollment is likely to get worse. To help people stay continuously covered, the federal government and the states could consider simplifying and streamlining the enrollment and reenrollment processes.

- Extend the marketplace open-enrollment period. The current open-enrollment period lasts just 45 days. Six states that run their own marketplaces have longer periods, some by as much as an additional 45 days. Other states, as well as the federal marketplace, could extend their enrollment periods as well.

IMPROVE INDIVIDUAL-MARKET PLANS’ COST PROTECTIONS

- Fund and extend the cost-sharing reduction subsidies. The Trump administration eliminated payments to insurers for offering plans with lower deductibles and copayments. Insurers, which by law must still offer reduced-cost plans, are making up the lost revenue by raising premiums. But this fix, while benefiting enrollees who are eligible for premium tax credits, has distorted both insurer pricing and consumer choice.21 In addition, it is unknown whether the administration’s support for the fix will continue in the future, creating uncertainty for insurers.22 Congress could reinstate the payments to insurers and consider making the plans available to people with higher earnings.

- Increase the number of services excluded from the deductible.Most plans sold in the individual market exclude certain services from the deductible, such as primary care visits and certain prescriptions.23As the survey data suggest, these types of exclusions appear to be important in ensuring access to preventive care among people who have coverage but are underinsured. In 2016, HHS provided a standardized plan option for insurers that excluded eight health services — including mental health and substance-use disorder outpatient visits and most prescription drugs — from the deductible at the silver and gold level.24 The Trump administration eliminated the option in 2018. Congress could make these exceptions mandatory for all plans.

IMPROVE EMPLOYER PLANS’ COST PROTECTIONS

- Increase the ACA’s minimum level of coverage. Under the ACA, people in employer plans may become eligible for marketplace tax credits if the actuarial value of their plan is less than 60 percent, meaning that under 60 percent of health care costs, on average, are covered. Congress could increase this to the 70 percent standard of silver-level marketplace plans, or even higher.

- Require deductible exclusions. Congress could require employers to increase the number of services that are covered before someone meets their deductible. Most employer plans exclude at least some services from their deductibles.25 Congress could specify a minimum set of exclusions for employer plans that might resemble the standardized-choice options that once existed for ACA plans.

- Refundable tax credits for high out-of-pocket costs. Congress could make refundable tax credits available to help insured Americans pay for qualifying out-of-pocket costs that exceed a certain percentage of their income.26

- Protect consumers from surprise medical bills. Several states have passed laws that protect patients and their families from unexpected medical bills, generally from out-of-network providers.27A bipartisan group of U.S. senators has proposed federal legislation to protect consumers, including people enrolled in employer and individual-market plans.

Health care costs are primarily what’s driving growth in premiums across all health insurance markets. Employers and insurers have kept premiums down by increasing consumers’ deductibles and other cost-sharing, which in turn is making more people underinsured. This means that policy options like the ones we’ve highlighted above will need to be paired with efforts to slow medical spending. These could include changing how health care is organized and providers are paid to achieve greater value for health care dollars and better health outcomes.28 The government also could tackle rising prescription drug costs29 and use antitrust laws to combat the growing concentration of insurer and provider markets.30