Category Archives: Change Agent

Healthcare groups call racism a ‘public health’ concern in wake of tensions over police brutality

After days of protests across the world against police brutality toward minorities sparked by the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, healthcare groups are speaking out against the impact of “systemic racism” on public health.

“These ongoing protests give voice to deep-seated frustration and hurt and the very real need for systemic change. The killings of George Floyd last week, and Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor earlier this year, among others, are tragic reminders to all Americans of the inequities in our nation,” Rick Pollack, president and CEO of the American Hospital Association (AHA), said in a statement.

“As places of healing, hospitals have an important role to play in the wellbeing of their communities. As we’ve seen in the pandemic, communities of color have been disproportionately affected, both in infection rates and economic impact,” Pollack said. “The AHA’s vision is of a society of healthy communities, where all individuals reach their highest potential for health … to achieve that vision, we must address racial, ethnic and cultural inequities, including those in health care, that are everyday realities for far too many individuals. While progress has been made, we have so much more work to do.”

The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) also decried the public health inequality highlighted by the dual crises.

“The violent interactions between law enforcement officers and the public, particularly people of color, combined with the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on these same communities, puts in perspective the overall public health consequences of these actions and overall health inequity in the U.S.,” SHEA said in a statement. Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) executives called for health organizations to do more to address inequities.

“Over the past three months, the coronavirus pandemic has laid bare the racial health inequities harming our black communities, exposing the structures, systems, and policies that create social and economic conditions that lead to health disparities, poor health outcomes, and lower life expectancy,” said David Skorton, M.D., AAMC president and CEO, and David Acosta, M.D., AAMC chief diversity and inclusion officer, in a statement.

“Now, the brutal and shocking deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery have shaken our nation to its core and once again tragically demonstrated the everyday danger of being black in America,” they said. “Police brutality is a striking demonstration of the legacy racism has had in our society over decades.”

They called on health system leaders, faculty researchers and other healthcare staff to take a stronger role in speaking out against forms of racism, discrimination and bias. They also called for health leaders to educate themselves, partner with local agencies to dismantle structural racism and employ anti-racist training.

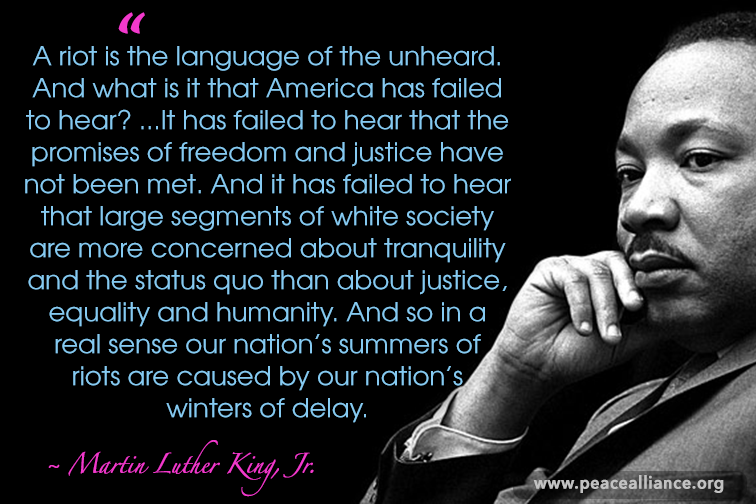

“What is it that America has failed to hear?”

https://mailchi.mp/9f24c0f1da9a/the-weekly-gist-june-5-2020?e=d1e747d2d8

“What is it that America has failed to hear?” asked Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in March of 1968, calling riots the “language of the unheard”. “It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met.” Stubbornly, shamefully, we continue to turn a deaf ear: to structural racism; to institutionalized inequality; to a pandemic of police brutality and bigotry that chokes off the breath of black Americans as surely as a virus in the lungs or a boot on the neck. But the sound in the streets is thunderous.

We in healthcare must listen. We must hear that what killed George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor, and Eric Garner, and Tamir Rice, and Philando Castile, and Trayvon Martin, and Ahmaud Arbery, and countless others, as surely as the terrible actions of any single person, was the pervasive, insidious virus of racism, long since grown endemic in our country.

This week’s protests are a kind of ventilator, providing emergency breath for a national body in crisis. We must work—urgently—on the therapeutics of structural change and the vaccines of education and understanding.

At Gist Healthcare we are listening, and learning. As a team, we’ve committed to each other to be attentive, invested, empathetic allies, and to dedicate our individual and collective time, talents and treasure to antiracist work, in healthcare and beyond. Our contribution may not be large, and it will never be enough, but at least we hope it will be positive. We’d like to hear your thoughts and suggestions as well. For the moment, and for our colleagues, friends, and families, we stand with the protestors.

Black Lives Matter.

Cartoon – The New Policy

Cartoon – Importance of Managing Change

Nobel Economist Says Inequality is Destroying Democratic Capitalism

Nobel Economist Says Inequality is Destroying Democratic Capitalism

At the launch of the IFS Deaton Review, a 5-year review of rising inequalities in the UK, Sir Angus Deaton decried extreme inequality and the system that allows it. “As it is, capitalism is not delivering to large fractions of the population.”

We are about to embark on a large, ambitious, and open-ended review of inequalities. We are bringing together a distinguished group of scholars and writers from different disciplines. Each thinks about inequality differently, and together they encompass a wide range of methodological, political, and philosophical perspectives. At a first stage, currently underway, the guiding panel is asking each member of this larger group to write about one or other aspect of the topic; this collective effort will be one of our main products. At the second stage, the panel will write a synthetic volume. We will think about inequalities broadly—note my use of “inequalities” rather than “inequality”—and will not be confined to the traditional economic concerns with measures of the distribution of income and wealth, important although those are. Our main focus is the United Kingdom, but there is a great deal of recent thinking and evidence from other countries, particularly the United States, Scandinavia, and other European countries, and we shall repeatedly have to assess its relevance, and are often asking authors or combinations of authors to make the links.

As at no other time in my lifetime, people are troubled by inequality. In 2016, Theresa May, in her first speech as Prime Minister, said “we believe in a union not just between the nations of the United Kingdom but between all of our citizens, every one of us, whoever we are and wherever we’re from. That means fighting against the burning injustice that, if you’re born poor, you will die on average 9 years earlier than others.” Jeremy Corbyn has called for a new economics to address what he called “Britain’s grotesque inequality.” President Obama said that he believed that the defining challenge of our time is to make sure that the US economy works for every American. Across the rich world, not only in America, large groups of people are currently questioning whether their economies are working for them. The same can be said of politics. Two-thirds of Americans without a college degree believe that there is no point in voting, because elections are rigged in favor of big business and the rich. Britain is divided as never before and, once again, many believe that their voice doesn’t count either in Brussels or in Westminster. And one of the greatest miracles of the 20th century, the miracle of falling mortality and rising lifespans, is no longer delivering for everyone, and is now faltering or reversing.

Yet when people say that they are worried about inequality, it is frequently unclear what they mean or why they care. Economists think they know what they mean when they talk about inequality, and they produce charts of gini coefficients of income and of wealth, and when other social scientists say that they have wider concerns, economists—among whom I count myself—have often been too ready to tell them that they don’t know what they are talking about. What we would like to do in this review, even with its large quota of economists, is to get a better understanding of exactly what it is that bothers people about inequality.

We will also think about how we might address concerns about inequality and which concerns need to be addressed. If the concern with inequality is simply envy—as is often claimed by the right—it is perhaps better to address the concern than the inequality. If the inequality comes from incentives that work for a few but benefit many, then we may want to do a better job of documenting the need for incentives and what they do for the economy as a whole. If working people are losing out because corporate governance is set up to favor shareholders over workers, or because the decline in unions has favored capital over labor and is undermining the wages of workers at the expense of shareholders and corporate executives, then we need to change the rules. Why are the myriad differences between men and women so persistent and so difficult to erase?

Given that we are just starting, it is perhaps presumptuous of me to say anything substantive at this point. But what I am going to say is what I myself think, or at least what I think today, and I look forward to changing my mind as we go; I wouldn’t be chairing this review if I didn’t expect that to happen. I am also perhaps too much influenced by my own work—particularly my recent work with Anne Case—and this work is primarily about the United States, though we have been doing quite a bit of thinking about how it applies to Britain.

At the risk of grandiosity, I think that today’s inequalities are signs that democratic capitalism is under threat, not only in the US, where the storm clouds are darkest, but in much of the rich world, where one or more of politics, economics, and health are changing in worrisome ways. I do not believe that democratic capitalism is beyond repair nor that it should be replaced; I am a great believer in what capitalism has done, not only to the oft-cited billions who have been pulled out of poverty in the last half-century, but to all the rest of us who have also escaped poverty and deprivation over the last two and a half centuries. It also provides our jobs and the cornucopia of goods and services that we take for granted. And Milton Friedman, whose starry-eyed view of capitalism has much to answer for, was not entirely wrong when he extolled the freedom that free markets can bring. Though history has not been kind to his view that equality would be guaranteed by using markets to pursue freedom.

But we need to think about repairs for democratic capitalism, either by fixing what is broken, or by making changes to head off the threats; indeed, I believe that those of us who believe in social democratic capitalism should be leading the charge to make repairs. As it is, capitalism is not delivering to large fractions of the population; in the US, where the inequalities are clearest, real wages for men without a four-year college degree have fallen for half a century, even at a time when per capita GDP has robustly risen. Mortality rates are rising for the less-educated group at ages 25 through 64, and by enough that life expectancy for the entire population has fallen for three years in a row, the first time such a reversal has happened since the end of the first world war and the great influenza epidemic. Less educated Americans are dying by their own hands, from suicide, from alcoholic liver disease, and from overdoses of drugs. Morbidity is rising too, and they are also suffering from an epidemic of chronic pain that, for many, makes a misery of daily life.

In Britain, these inequalities are not so stark, at least not yet. But median real wages in Britain have not risen for more than a decade. One decade is much better than five decades, but we surely do not want to wait to find out whether the American experience will be replicated here. There have also been prolonged periods of real wage stagnation in recent years in Italy and in Germany. In those countries too, increasing overall prosperity is not reaching everyone. And as I noted above, democracy too does not seem to be working for everyone. The sense of being left behind, of not being represented at Westminster, is much the same as the sense of not being represented in Washington.

In Clement Attlee’s 1945 cabinet—the cabinet that implemented the Beveridge Report and built the first modern welfare state—there were seven men who had begun their working lives at the coal face. When labor MPs from Glasgow set off to London, local bands and choirs came to the station to see them off as if they were going to war, which indeed they were. Only three percent of MPs elected in 2015 were ever manual workers, compared with sixteen percent as recently as 1979. The union movement, which once produced talents like those in Attlee’s cabinet, has been gutted by the success of postwar meritocracy. Attlee’s warriors would today have gone to university and become professionals; they would never have been down the pit, nor in a union hall. Meritocracy has many virtues, but, as predicted by Michael Young in 1958, it has deprived those who didn’t pass the exams, not only of social status and of the higher incomes that degrees bring, but even of the kind of political representation that comes from having people like themselves in parliament. Young wrote, “The bargaining over the distribution of national expenditure is a battle of wits, and defeat is bound to go to those who lost their clever children to the enemy.” He referred to the less educated group as “the populists” who, in turn, refer to the elite as “the hypocrisy.”

What does history tell us? Not surprisingly, we have been here before. There have been several episodes where capitalism seemed broken, but was repaired, either on its own, or by deliberate policy, or by a combination of the two.

In Britain at the beginning of the 19th century, inequality was vast compared with today. The hereditary landowners not only were rich, but also controlled parliament through a severely limited franchise. After 1815, the notorious Corn Laws prohibited imports of wheat until the local price was so high that people were at risk of starving; high prices of wheat, even if they hurt ordinary people, were very much in the interests of the land-owning aristocracy, who lived off the rents supported by the restriction on imports. The Industrial Revolution had begun, there was a ferment of innovation and invention, and national income was rising. Yet working people were not benefitting. Mortality rates rose as people moved from the relatively healthy countryside to stinking, unsanitary cities. Each generation of military recruits was shorter than the last as their childhood nutrition worsened, from not getting enough to eat and from the nutritional insults of unsanitary conditions. Churchgoing fell, removing a major source of community and support for working people, if only because churches were in the countryside, not in the new industrial cities. Wages were stagnant and would remain so for half a century. Profits were rising, and the share of profits in national income rose at the expense of labor. It would have been hard to predict a positive outcome of this process.

Yet by century’s end, the Corn Laws were gone, the rents and fortunes of the aristocrats had fallen along with the world price of wheat. Reform Acts had extended the franchise, from one in ten males at the beginning of the century to more than a half by its end, though the enfranchisement of women would wait until 1918. Wages had begun to rise in 1850, and the more than century-long decline in mortality had begun. All of this happened without a collapse of the state, without a war, or a pandemic, through a gradual change in institutions that slowly gave way to the demands of those who had been left behind.

America’s first Gilded Age is another case. It also shows that the fundamental rules of the game can be changed. In the Progressive Era, four constitutional amendments were passed, all designed to limit inequality of one form or another. One instituted the income tax, one gave women the vote, one prohibited alcohol—strongly supported by women, who believed that alcohol abuse was an instrument of their oppression—and one an electoral reform that instituted the direct election of senators, as opposed to their previous appointment by state legislatures that were often dominated by business.

I have already mentioned the case that is most on my mind, the construction of the modern welfare state by Attlee’s government after the Second World War. The Great Depression, like the stagnation of wages in the early 1800s, spawned a large literature on how to modify or abolish capitalism, and according to one version of the story, it was Attlee’s government that tamed the beast and that made it possible for the tamed beast to deliver the unprecedented shared growth that many of us grew up on. Joe Stiglitz has recently written that he grew up in the golden age of capitalism though, as he wryly notes, it was only later that he discovered that it was the golden age. And, of course, it wasn’t a golden age—at least in terms of material living standards or in terms of health—but perhaps it was such in terms of the rules of the game that allowed growing prosperity to be widely shared. I don’t think that anyone would argue that the late 1940s was a golden age in Britain— there was bread rationing, petrol rationing, and to a young Angus Deaton, the terrible deprivation of sweet rationing, but the safety net that was built in those years played a role in fairly sharing, and perhaps even in helping generate, the prosperity that was to come.

That safety net is needed just as much today. Globalization and automation are challenging us today just as they did in the early 19th century. Safety nets are most needed when change is rapid, and it is one of the reasons why America is doing so much worse—most obviously in deaths of despair—than are wealthy European countries. But what is happening today is also a real threat to Britain and to Europe.

The argument that Anne Case and I are making in our new book is that less-educated white men and women in America have had their lives progressively undermined, starting in the 1970s, and showing up, since 1990, in rising numbers of deaths from suicide, alcoholic liver disease, and drug overdoses. African Americans experienced a similar disaster thirty years earlier and the improvements in their lives since then have protected them to an extent. In the face of globalization and innovation, many of us would argue that American policy, instead of cushioning working people, has instead contributed to making their lives worse, by allowing more rent-seeking, reducing the share of labor, undermining pay and working conditions, and changing the legal framework in ways that favor business over workers. Inequality has risen not only due to wealth generation from innovation or creation, but also through upward transfers from workers. It is not inequality itself that is hurting people, but the mechanisms of enrichment.

How much is this a threat in Britain? Some of the mechanisms of enrichment are not operative here. The US wastes about a trillion dollars a year on a healthcare system that is very good at enriching providers, hospitals, device manufacturers, and pharmaceutical companies, but very bad at delivering health. You do not have that problem. The US has licensed pharma companies to sell opioids to the general public, including for chronic pain, which ignited an epidemic of addiction and death with a cumulative death toll larger than all Americans lost in both World Wars. You too use opioids, but usually in hospitals, not in the general population. Yet the opioid manufacturers are following the model of tobacco manufacturers, and working hard, when blocked in the US, to expand elsewhere. Purdue Pharma has a subsidiary, Mundipharma, that agitates on behalf of the greater pain relief that they argue opioids can bring. As I write this, Matt Hancock, the Minister of Health, noted that “things are not as bad here as in America, but we must act now to protect people from the darker side of painkillers.” The BBC news report on this carries a chart showing the extraordinary geographical inequality in opioid prescriptions in England, with prescription rates five times larger in Cumbria and the North East than in London. As the briefing note for this launch shows, deaths of despair are rising in Britain, particularly in less successful parts of Britain, just as they are in other English-speaking countries, though the numbers (and death rates) are small compared with the US.

What about wages? The US has extensive business lobbying, which the UK does not have, or at least not in the same overt form. (The US also had very little prior to 1970, so it could happen here too.) As in the US, unions have become much less powerful in Britain, a decline that many have welcomed, but their countervailing power in boardroom decisions may have protected wages and working conditions. Unions provided social life and political power for many people who have less of both today. The replacement of stakeholder capitalism by shareholder value maximization is widespread in the US and has been remarked on here, too. Paul Collier has noted that Imperial Chemical Industries, once the crown jewel of British industry, used to boast “we aim to be the finest chemical company in the world,” but that, before it was lost to takeovers and mergers in 2006, it had changed its slogan to “we aim to maximize shareholder valuation.”

In Britain, as in America, some cities and towns are doing much better than other cities and towns, and the easy mobility that tended to keep these differences in check seems to have been much reduced. America has no city that is as dominant or as uniquely prosperous as is London.

Political dysfunction in Britain is different, but there is a common thread that many voters believe that they are not well represented. And there are sharp differences across groups, with age, education, ethnicity, gender and geography important in both countries.

I think that people getting rich is a good thing, especially when it brings prosperity to others. But the other kind of getting rich, “taking” rather than “making,” rent-seeking rather than creating, enriching the few at the expense of the many, taking the free out of free markets, is making a mockery of democracy. In that world, inequality and misery are intimate companions.

The One Most Responsive to Change

The evolution of the CFO

CFOs are playing an increasingly pivotal role in driving change in their companies. How should they balance their traditional responsibilities with the new CFO mandate?

Podcast transcript

Sean Brown: If you wanted evidence that the only constant in life is change, then look no further than the evolution of the CFO role. In addition to traditional CFO responsibilities, results from a recent McKinsey survey suggest that the number of functions reporting to CFOs is on the rise. Also increasing is the share of CFOs saying they oversee their companies’ digital activities and resolve issues outside the finance function. How can CFOs harness their increasing responsibilities and traditional finance expertise to drive the C-suite agenda and lead substantive change for their companies?

Joining us today to answer that question are Ankur Agrawal and Priyanka Prakash. Ankur is a partner in our New York office and one of the leaders of the Healthcare Systems & Services Practice. Priyanka is a consultant also based in New York. She is a chartered accountant by training and drives our research on the evolving role of finance and the CFO. Ankur, Priyanka, thank you so much for joining us today.

Let’s start with you, Ankur. Tell us about your article, which is based on a recent survey. What did you learn?

Ankur Agrawal: We look at the CFO role every two years as part of our ongoing research because the CFO is such a pivotal role in driving change at companies. We surveyed 400 respondents in April 2018, and we subsequently selected a few respondents for interviews to get some qualitative input as well. Within the 400 respondents, 212 of those were CFOs, and then the remainder were C-level executives and finance executives who were not CFOs. We had a healthy mix of CFOs and finance executives versus nonfinance executives. The reason was we wanted to compare and contrast what CFOs are saying versus what the business leaders are saying to get a full 360-degree view of CFOs.

The insights out of this survey were many. First and foremost, the pace of change in the CFO role itself is shockingly fast. If we compare the results from two years ago, the gamut of roles that reported into the CFO role has dramatically increased. On average, approximately six discrete roles are reporting to the CFO today. Those roles range from procurement to investor relations, which, in some companies, tend to be very finance specific. Two years ago, that average was around four. You can see the pace of change.

The second interesting insight out of this survey when compared to the last survey is the cross-functional nature of the role, which is driving transformations and playing a more proactive role in influencing change in the company. The soft side of the CFO leadership comes out really strongly, and CFOs are becoming more like generalist C-suite leaders. They should be. They, obviously, are playing that role, but it is becoming very clear that that’s what the business leaders expect them to do.

And then two more insights that are not counterintuitive, per se, but the pace of change is remarkable. One is this need to lead on driving long-term performance versus short-term performance. The last couple of years have been very active times for activist investors. There are lots of very public activist campaigns. We clearly see in the data that CFOs are expected to drive long-term performance and be the stewards of the resources of the company. That data is very clear.

And then, lastly, the pace of change of technology and how it’s influencing the CFO role: more than half of the CFO functions or finance functions are at the forefront of digitization, whether it is automation, analytics, robotic processes, or data visualization. More than half have touched these technologies, which is remarkable. And then many more are considering the technological evolution of the function.

Sean Brown: In your survey, did you touch on planning for the long term versus the short term?

Ankur Agrawal: Our survey suggests, and lot of the business leaders suggest, that there is an imperative for the CFO to be the steward of the long term. And there is this crying need for the finance function to lead the charge to take the long-term view in the enterprise. What does that mean? I think it’s hard to do—very, very hard to do—because the board, the investors, everybody’s looking for the short-term performance. But it puts even more responsibility on the finance function in defining and telling the story of how value is being created in the enterprise over the long term. And those CFOs and finance executives who are able to tell that story and have proof points along the way, I think those are the more successful finance functions. And that was clearly what our survey highlighted.

What it also means is the finance functions have to focus and put in place KPIs [key performance indicators] and metrics that talk about the long-term value creation. And it is a theme that has been picked up, in the recent past, by the activists who have really taken some companies to task on not only falling short on short-term expectations but also not having a clear view and road map for long-term value creation. It is one of the imperatives for the CFO of the future: to be the value architect for the long term. It’s one of the very important aspects of how CFOs will be measured in the future.

Sean Brown: I noticed in your survey that you did ask CFOs and their nonfinance peers where they thought CFOs created the most value. What did you learn from that?

Priyanka Prakash: This has an interesting link with the entire topic of transformation. We saw that four in ten CFOs say that they created the most value through strategic leadership, as well as leading the charge on talent, including setting incentives that are linked with the company’s strategy. However, we see that nonfinance respondents still believe that CFOs created the most value by spending time on traditional finance activities. This offers an interesting sort of split. One of the things that this indicates is there’s a huge opportunity for CFOs to lead the charge on transformation to ensure that they’re not just leading traditional finance activities but also being change agents and leading transformations across the organization.

Ankur Agrawal: The CFOs of the future have to flex different muscles. They have been very good in really driving performance. Maybe there’s an opportunity to even step up the way that performance is measured in the context of transformation, which tends to be very messy. But, clearly, CFOs are expected to be the change agents, which means that they have to be motivational. They have to be inspirational. They have to lead by example. They have to be cross-functional. They have to drive the talent agenda. It’s a very different muscle, and the CFOs have had less of an opportunity to really leverage that muscle in the past. I think that charismatic leadership from the CFO will be the requirement of the future.

Sean Brown: You also address the CFO’s role regarding talent. Tell us a bit more about that.

Ankur Agrawal: Another really important message out of the survey is seeing the finance function and the CFO as a talent factory. And what that means is really working hand in hand with the CEO and CHRO [chief HR officer] over this trifecta of roles. Because the CFO knows where to invest the money and where the resources need to be allocated to really drive disproportionate value, hopefully for the long run. The CHRO is the arbiter of talent and the whole performance ethic regarding talent in the company. And the CEO is the navigator and the visionary for the company. The three of them coming together can be a very powerful way to drive talent—both within the function and outside the function.

And the finance-function leaders expect CFOs to play a really important role in talent management in the future and in creating the workforce of the future. And this workforce—in the finance function, mind you—will be very different. There’s already lots of talk about a need for data analytics, which is infused in the finance function and even broader outside the organization of finance function. The CFOs need to foster that talent and leverage the trifecta to attract, retain, and drive talent going forward.

Sean Brown: Do you have any examples of successful talent-development initiatives for the finance function? And can you share any other examples of where CFOs, in particular, have taken a more active role in talent and talent development?

Ankur Agrawal: An excellent question. On talent development within the finance function, a few types of actions—and these are not new actions—done very purposefully can have significant outsize outcome. One is job rotations: How do you make sure that 20 to 30 percent of your finance function is moving out of the traditional finance role, going out in the business, learning new skills? And that becomes a way where you cultivate and nurture new skills within the finance function. You do it very purposefully, without the fear that you will lose that person. If you lose that person, that’s fine as well. That is one tried-and-tested approach. And some companies have made that a part of the talent-management system.

The second is special projects. And again, it sounds simple, but it’s hard to execute. This is making this a part of every finance-function executive’s role, whether it’s a pricing project or a large capex [capital-expenditure] and IT project implementation. Things like that. Getting the finance function outside of their comfort zone: I think that’s certainly a must-have.

And the third would be there is value in exposing finance-function executives to new skills and creating a curriculum, which is very deliberate. I think technology’s changing so rapidly. So exposing the finance function to newer technologies, newer ways of working, and collaboration tools: those are the things I would highlight as ways to nurture finance talent.

Priyanka Prakash: Just to add onto that. A lot of the folks whom I talked to say that, very often, finance folks spend a large chunk of their time trying to work on ad hoc requests that they get from the other parts of the business. A big opportunity here is in how the finance function ensures that the rest of the nonfinance part has some basic understanding of finance to make them more self-sufficient, to ensure that they are not coming to the finance function with every single question. What this does is it ensures that the rest of the organization has the finance skills to ensure that they’re making the right decisions, using financial tools.

And secondly, it also significantly frees up the way that the finance organization itself spends its time. If they spend a few hours less working on these ad hoc requests, they can invest their time in thinking about strategy, in thinking about how the finance function can improve the decision making. I think that’s a huge sort of benefit that organizations have seen just by upscaling their nonfinance workforce to equip them with the financial skills to ensure that the finance team is spending time on its most high-value activity.

Sean Brown: Is this emphasis on talent focused only on the finance function? What I am hearing from your response is that it’s not just building up the talent within the finance function but embedding finance talent and capabilities throughout the organization. Is that right?

Priyanka Prakash: Absolutely. Because if you take an example of someone who’s in a factory who wants to have an investment request for something that they want to do at a plant, they will have to know the basic knowledge of finance to evaluate whether this is an investment that they need or not. Because at the end of the day, any decision would be incomplete without a financial guideline on how to do it. I think that the merging of your other functions with a strong background and rooting in finance can improve the quality of decisions that not just the finance function but other teams and other functions also make in the organization.

Sean Brown: Priyanka, your survey touches a bit on the topic of digital. What did you learn there?

Priyanka Prakash: Sure. This is one of those things that everybody wants to do, but the question that I’ve seen most of my clients struggle with in the initial phases is, “Yes, I have the intent from the top. There is intent from the finance and other teams on how to become more digital, but how do you actually start that process?”

There are four distinct kinds of technologies or tools that finance teams, specifically, could use in enabling their digital journey and transformation. CFOs have way too much on their plates right now. What this essentially means is that they need to invest time and a lot of their thinking into some of these newer, more strategic areas while ensuring that they keep the lights on in the traditional finance activities. The biggest tool that will enable them to keep the lights on as well as add value in this new expanded role is to take advantage of automation, as well as some of the newer digital technologies that we see.

There are basically four types of digital stages that we see as finance functions start to evolve. One is using automation, which is typically the first step. For example, “How do I move from an Excel-based system to an Alteryx one? How do I move from a manual transactional system to something that’s more automated, where my finance teams don’t have to invest time, but it happens in the background with accuracy?” That’s step one.

The second thing that we see as a result of this is you have a lot of data-visualization tools that are being used. This is very helpful, especially when you think about the role of FP&A [financial planning and analysis]. “How does my FP&A team ensure that the company makes better decisions? How do I use a visualization software to get different views of my data to ensure that I’m making the right decisions?”

The third one is, “How do I use analytics within finance? How do I use analytics to draw insights from the data that I might have missed otherwise?” This could be something in forecasting. This could be something in planning. But this could also be something that’s used when you compare your budget or your forecast. Your analytics could really help draw out drivers of why there’s a variance.

And fourthly is, “How do I then integrate this advanced-analytics philosophy across the rest of the company?” What this means is, “How do I integrate my finance and traditional ERP [enterprise-resource-planning] systems with the pricing system, with the operations, and supply-chain-management system? How do I integrate my finance systems with my CRM [customer relationship management]?” Again, the focus is on ensuring that the whole database is not this large, clunky system but an agile system that ensures you draw out some insights.

Sean Brown: Some have suggested the CFO is ideally suited to be the chief digital officer. Have you seen any good examples of this?

Ankur Agrawal: There were examples even before the digital technologies took over. In some companies, the technology functions used to report to CFOs. There are cases where CFOs have formally or even informally taken over the mandate of a chief digital officer. You don’t necessarily need to have a formal reporting role to be a digital leader in the company. CFOs, of course, have an important role in vetting expenses and vetting the investments the companies are making. That said, CFOs have this cross-functional visibility of the entire business, which makes them very well suited to being the digital officers. In some cases, CFOs have stepped up and played that more formal role. I would expect, in the future, they will certainly have an informal role. In select cases, they will continue to have a formal digital-officer role.

Sean Brown: It sounds like, from the results of the survey, the CFO has a much larger role to play. Where does someone begin on this journey?

Priyanka Prakash: Going back to the first point that we discussed on how CFOs should help their companies have a more long-term view, we see that this transformation is specifically here to move to more digital technologies. It’s not going to be easy, and it’s not going to be short. Yes, you will see quick wins. But it is going to be a slightly lengthy—and oftentimes, a little bit of a messy—process, especially in the initial stages. How do we ensure that there is enough leadership energy around this? Because once you have that leadership energy, and once you take the long-term view to a digital transformation, the results that you see will pay for themselves handsomely.

Again, linking this back with the long-term view, this is not going to be a short three-month or six-month process. It’s going to be an ongoing evolution. And the nature of the digital technologies also evolve as the business evolves. But how do you ensure that your finance and FP&A teams have the information and the analytics that they need to evolve and be agile along with the business and to ensure that the business responds to changes ahead of the market? How do we ensure that digital ensures that your company is proactively, and not reactively, reacting to changes in the external market and changes in disruption?

Sean Brown: Priyanka, any final thoughts you’d like to share?

Priyanka Prakash: All that I’ll say is that this is a very, very exciting time for the role of the CFO. A lot of things are changing. But you can’t evolve unless you have your fundamentals right. This is a very exciting time, where CFOs can have the freedom to envision, create, and chart their own legacy and then move to a leadership and influencer role and truly be a change agent in addition to doing their traditional finance functions, such as resource allocation, your planning, and all of the other functions as well. But I definitely do think that these are very exciting times for finance organizations. There are lots of changes, and the evolutionary curve is moving upward very quickly.

Sean Brown: Ankur, Priyanka, thanks for joining us today.

The new CFO mandate: Prioritize, transform, repeat

Amid a raft of new duties for CFOs, our survey suggests that finance leaders are well positioned to lead the C-suite agenda by championing transformations, digitization, and capability building.

Responses indicate that the opportunity for CFOs to establish the finance function as both a leading change agent and a source of competitive advantage has never been greater. Yet they also show a clear perception gap that must be bridged if CFOs are to break down silos and foster the collaboration necessary to succeed in a broader role. While CFOs believe they are beginning to create financial value through nontraditional tasks, they also say that a plurality of their time is still devoted to traditional tasks versus newer initiatives. Meanwhile, leaders outside the finance function believe their CFOs are still primarily focused on and create the most value through traditional finance tasks.

How can CFOs parlay their increasing responsibility and traditional finance expertise to resolve these differing points of view and lead substantive change for their companies? The survey results point to three ways that CFOs are uniquely positioned to do so: actively heading up transformations, leading the charge toward digitization, and building the talent and capabilities required to sustain complex transformations within and outside the finance function.

Changing responsibilities, unchanged perceptions

The latest survey results confirm that the CFO’s role is broader and more complex than it was even two years ago. The number of functional areas reporting to CFOs has increased from 4.5 in 2016 to an average of 6.2 today. The most notable increases since the previous survey are changes in the CFO’s responsibilities for board engagement and for digitization (that is, the enablement of business-process automation, cloud computing, data visualization, and advanced analytics). The share of CFOs saying they are responsible for board-engagement activities has increased from 24 percent in 2016 to 42 percent today; for digital activities, the share has doubled.

The most commonly cited activity that reports to the CFO this year is risk management, as it was in 2016. In addition, more than half of respondents say their companies’ CFOs oversee internal-audit processes and corporate strategy. Yet CFOs report that they have spent most of their time—about 60 percent of it, in the past year—on traditional and specialty finance roles, which was also true in the 2016 survey.

Also unchanged are the diverging views, between CFOs and their peers, about where finance leaders create the most value for their companies. Four in ten CFOs say that in the past year, they have created the most value through strategic leadership and performance management—for example, setting incentives linked to the company’s strategy. By contrast, all other respondents tend to believe their CFOs have created the most value by spending time on traditional finance activities (for example, accounting and controlling) and on cost and productivity management across the organization.

Finance leaders also disagree with nonfinance respondents about the CFO’s involvement in strategy decisions. CFOs are more likely than their peers to say they have been involved in a range of strategy-related activities—for instance, setting overall corporate strategy, pricing a company’s products and services, or collaborating with others to devise strategies for digitization, analytics, and talent-management initiatives.

Guiding and sustaining change

Our latest survey, along with previous McKinsey research,2 confirms that large-scale organizational change is ubiquitous: 91 percent of respondents say their organizations have undergone at least one transformation in the past three years.3 The results also suggest that CFOs are already playing an active role in transformations. The CFO is the second-most-common leader, after the CEO, identified as initiating a transformation. Furthermore, 44 percent of CFO respondents say that the leaders of a transformation, whether it takes place within finance or across the organization, report directly to them—and more than half of all respondents say the CFO has been actively involved in developing transformation strategy.

Respondents agree that, during transformations, the CFO’s most common responsibilities are measuring the performance of change initiatives, overseeing margin and cash-flow improvements, and establishing key performance indicators and a performance baseline before the transformation begins. These are the same three activities that respondents identify as being the most valuable actions that CFOs could take in future transformations.

Beyond these three activities, though, respondents are split on the finance chief’s most critical responsibilities in a change effort. CFOs are more likely than peers to say they play a strategic role in transformations: nearly half say they are responsible for setting high-level goals, while only one-third of non-CFOs say their CFOs were involved in objective setting. Additionally, finance leaders are nearly twice as likely as others are to say that CFOs helped design a transformation’s road map.

Other results confirm that finance chiefs have substantial room to grow as change leaders—not only within the finance function but also across their companies. For instance, the responses indicate that half of the transformations initiated by CFOs in recent years were within the finance function, while fewer than one-quarter of respondents say their companies’ CFOs kicked off enterprise-wide transformations.

Leading the charge toward digitization and automation

The results indicate that digitization and strategy making are increasingly important responsibilities for the CFO and that most finance chiefs are involved in informing and guiding the development of corporate strategy. All of this suggests that CFOs are well positioned to lead the way—within their finance functions and even at the organization level—toward greater digitization and automation of processes.

Currently, though, few finance organizations are taking advantage of digitization and automation. Two-thirds of finance respondents say 25 percent or less of their functions’ work has been digitized or automated in the past year, and the adoption of technology tools is low overall.

The survey asked about four digital technologies for the finance function: advanced analytics for finance operations,5 advanced analytics for overall business operations,6 data visualization (used, for instance, to generate user-friendly dynamic dashboards and graphics tailored to internal customer needs), and automation and robotics (for example, to enable planning and budgeting platforms in cloud-based solutions). Yet only one-third of finance respondents say they are using advanced analytics for finance tasks, and just 14 percent report the use of robotics and artificial-intelligence tools, such as robotic process automation (RPA).7 This may be because of what respondents describe as considerable challenges of implementing new technologies. When asked about the biggest obstacles to digitizing or automating finance work, finance respondents most often cite a lack of understanding about where the opportunities are, followed by a lack of financial resources to implement changes and a need for a clear vision for using new technologies; only 3 percent say they face no challenges.

At the finance organizations that have digitized more than one-quarter of their work, respondents report notable gains from the effort. Of these respondents, 70 percent say their organizations have realized modest or substantial returns on investment—much higher than the 38 percent of their peers whose finance functions have digitized less than one-quarter of the work.

Unlocking the power of talent

The survey results also suggest that CFOs have important roles to play in their companies’ talent strategy and capability building. Since the previous survey, the share of respondents saying CFOs spend most of their time on finance capabilities (that is, building the finance talent pipeline and developing financial literacy throughout the organization) has doubled. Respondents are also much more likely than in 2016 to cite capability building as one of the CFO’s most value-adding activities.

Still, relative to their other responsibilities, talent and capabilities don’t rank especially high—and there are opportunities for CFOs to do much more at the company level. Just 16 percent of all respondents (and only 22 percent of CFOs themselves) describe their finance leaders’ role as developing top talent across the company, as opposed to developing talent within business units or helping with talent-related decision making. And only one-quarter of respondents say CFOs have been responsible for capability building during a recent transformation.

But among the highest-performing finance functions, the CFO has a much greater impact. Respondents who rate their finance organization as somewhat or very effective are nearly twice as likely as all others to say their CFOs develop top talent organization-wide (20 percent, compared with 11 percent). Among those reporting a very effective finance function, 38 percent say so.

Looking ahead

It’s clear from the numbers that CFOs face increased workloads and expectations, but they also face increased opportunities. In our experience, a focus on several core principles can help CFOs take advantage of these opportunities and strike the right balance:

- Make a fundamental shift in how to spend time. To be more effective in their new, ever-expanding roles, CFOs must carefully consider where to spend their time and energy. They should explore new technologies, methodologies, and management approaches that can help them decide how and where to make necessary trade-offs. It’s not enough for them to become only marginally more effective in traditional areas of finance; they must ensure that the finance organization is contributing more and more to the company’s most value-adding activities. It’s especially important, therefore, that CFOs are proactive in looking for ways to enhance processes and operations rather than waiting for turnaround situations or for their IT or marketing colleagues to take the lead.

- Embrace digital technologies. The results indicate that the CFO’s responsibilities for digital are quickly increasing. We also know from experience that finance organizations are increasingly becoming critical owners of company data—sometimes referred to as the “single source of truth” for their organizations—and, therefore, important enablers of organizational transformations. Finance leaders thus need to take better advantage and ownership of digital technology and the benefits it can bring to their functions and their overall organizations. But they cannot do so in a vacuum. Making even incremental improvements in efficiency using digital technologies (business intelligence and data-visualization tools, among many others) requires organizational will, a significant investment of time and resources, and collaboration with fellow business leaders. So, to start, CFOs should prioritize quick wins while developing long-term plans for how digitization can transform their organizations. They may need to prioritize value-adding activities explicitly and delegate or automate other tasks. But they should always actively promote the successes of the finance organization, with help from senior leadership.

- Put talent front and center. Since the previous survey, CFOs have already begun to expand their roles and increase their value through capability building and talent development. But the share of CFOs who spend meaningful, valuable time on building capabilities remains small, and the opportunity for further impact is significant. Finance leaders can do more, for instance, by coaching nonfinance managers on finance topics to help foster a culture of transparency, self-sufficiency, and value creation.