https://www.vox.com/2020/4/29/21231906/coronavirus-pandemic-summer-weather-heat-humidity-uv-light

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19924839/GettyImages_1220238213.jpg)

Summer weather could help slow the coronavirus. But it’s likely not enough.

Some Americans are hoping for a natural reprieve to social distancing as the coronavirus pandemic drags on: that sunnier, warmer, and more humid weather in the summer will destroy the Covid-19 virus — as it does with other viruses, like the flu — and let everyone go back to normal.

There is some evidence that heat, humidity, and ultraviolet light could hurt the coronavirus — an idea that President Donald Trump bizarrely leaned into when he suggested the use of “ultraviolet or just very powerful light … inside the body” to treat people sickened by Covid-19 (an idea with no scientific merit, as experts have repeatedly stated).

But even if heat, humidity, and light help slow the virus’s spread, sunny, hot, and humid weather alone won’t be enough to end the epidemic. Experts point to the examples of Singapore, Ecuador, and Louisiana, all of which have recently had growing numbers of Covid-19 cases despite temperatures hitting 80-plus degrees Fahrenheit and humidity levels reaching more than 60, 70, or even 80 percent.

High levels of heat, UV light, and humidity can help prevent more widespread infections of the flu or colds in the summer, along with medical treatments and vaccines (when available). But the Covid-19 coronavirus is still new to humans, so we don’t have as much immune protection built up against it — so the virus seems able to overcome summer-like weather and still cause big outbreaks.

“For the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, we have reason to expect that like other betacoronaviruses, it may transmit somewhat more efficiently in winter than summer, though we don’t know the mechanism(s) responsible,” Marc Lipsitch, an epidemiologist at Harvard, wrote. “The size of the change is expected to be modest, and not enough to stop transmission on its own.”

Still, the studies on heat, light, and humidity, plus the fact coronavirus has a harder time spreading in open-air areas, suggest that the outdoors may be a safe target for a slow reopening as transmission of the virus slows, as long as precautions like physical distancing and mask-wearing are followed. So outdoor activities could offer a respite to lockdowns and quarantines — one that’s also, potentially, good for physical and mental health.

It also means that if Covid-19 becomes endemic (a disease that regularly comes back, like the flu or common cold), then heat, sunlight, and humidity could restrict bigger outbreaks to fall and winter. But that possibility is likely still years away, experts say.

So summer weather may make the outdoors a little safer, but it won’t be enough to quash coronavirus on its own. That means we’ll likely need to continue social distancing to some degree in the coming months, and continue working on getting more testing, aggressive contact tracing, and medical treatments up to scale before places can safely reopen their economies.

Hotter, more humid weather does seem to hurt the coronavirus

There are a few ways that summer weather could have an effect on SARS-CoV-2. Higher temperatures can help weaken the novel coronavirus’s outer lipid layer, similar to how fat melts in greater heat. Humidity in the air can effectively catch virus-containing droplets that people breathe out, causing these droplets to fall to the ground instead of reaching another human host — making humidity a shield against infection. UV light, which there’s a lot more of during sunny summer days, is a well-known disinfectant that effectively fries cells and viruses.

“There are multiple coronaviruses out there that affect our population, and many of them, if not most of them, exhibit a seasonal influence,” Mauricio Santillana, the director of the Machine Intelligence Lab at Boston Children’s Hospital and a researcher on the effects of the weather on coronavirus, told me. “The hypothesis postulated for Covid-19 is that it will have a similar behavior.”

But that’s hypothetical. How does it play out in reality?

So far, the coronavirus has largely spread in the Northern Hemisphere, where it’s been winter and early spring. It’s not clear if the weather is a reason for that, because data on its spread in the Southern Hemisphere — particularly poorer countries in Africa and South America — is largely lacking due to weak public health infrastructure.

Still, we have some evidence. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine — one of America’s top scientific evidence reviewers — summarized the research earlier in April. It looked at two kinds of studies: those that tested the effects of summer-like temperatures in a laboratory, and those that attempted to tease out the effects of heat, UV light, and humidity in the real world.

In the lab, researchers use sophisticated tools to see how the virus fares in different conditions. Generally, they’ve found more heat, UV light, and humidity seem to weaken the coronavirus — although one preliminary study suggested that coronavirus may fare better in the more summer-like conditions than the flu, SARS, and monkeypox viruses.

This is the kind of study Bill Bryan, the undersecretary for science and technology at the Department of Homeland Security, presented at the April 23 White House press briefing. That study found that coronavirus seemed to die off much more quickly in hotter, more humid environments with a lot of UV light.

As the National Academies noted, however, this evidence comes with big caveats. Perhaps most importantly, these studies haven’t yet been peer reviewed. So they could have big methodological errors that we just don’t know about yet. (This Wired article does a good job breaking down the concerns with such early research.)

But even if these studies are well-conducted, the real world is simply a lot messier than a laboratory setting. For example, the lab-grown virus used in these studies may act at least somewhat differently than the natural virus in the real world.

People can also act differently in summer than they do in winter, and the lab studies don’t account for how those behaviors affect coronavirus’s spread. People are more likely to stay indoors during the winter to avoid the cold — but indoor spaces are generally more poorly ventilated and cramped, both of which make it easier for the coronavirus to spread. Warmth and sunshine also could impact the immune system, though that relationship is still unclear.

We’ll get more evidence on real-life seasonal effects as the months go by — especially if more places take potentially dangerous risks. “In Georgia, where they are opening back up without really any concrete measures to encourage distancing, we might be able to better evaluate how [the coronavirus] spreads in the summer months,” Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at Columbia, told me.

But there is some early real-world research already, which the National Academies also reviewed. These studies looked at whether the SARS-CoV-2 virus was affected by different climates in real-world settings, and if it spread more easily in places where it was colder and less humid and there was less UV light. Some researchers also developed models based on data from different outbreaks in different parts of the world.

One upcoming study from a group of researchers at the University of Nebraska Medical Center tried to model the effects of heat, humidity, and UV light, finding that they mitigated the spread of the virus. UV light seemed to play a bigger role, although the researchers cautioned that their findings will need to be replicated and verified with, ideally, years of data. “This is a very new virus, and there are lots of things we don’t know about it,” Azar Abadi, one of the researchers, told me.

But this aligns with the evidence that the National Academies reviewed.

“There is some evidence to suggest that SARS-CoV-2 may transmit less efficiently in environments with higher ambient temperature and humidity,” Harvey Fineberg, author of the National Academies report, wrote. “[H]owever, given the lack of host immunity globally, this reduction in transmission efficiency may not lead to a significant reduction in disease spread without the concomitant adoption of major public health interventions.”

Heat and humidity won’t be enough to beat the pandemic — far from it

This is the point experts emphasized again and again: It’s one thing for the weather to have some sort of effect on coronavirus; it’s another thing for that effect to be enough to actually halt the virus’s widespread transmission. We have early evidence the weather has an effect, but we also have early evidence that it won’t be enough.

The problem: Other factors, besides the weather, play a role in the spread of diseases. In the case of coronavirus, these other factors seem to play a much bigger role than weather.

The mayor of Guayaquil, Ecuador, where it’s regularly 80-plus degrees Fahrenheit, described her city’s experience with Covid-19 “like the horror of war” and “an unexpected bomb falling on a peaceful town.” Ecuador now has one of the worst coronavirus death tolls in the world — a sign that warm, sunny, and humid weather can’t make up for struggling public health infrastructure in a still-developing country.

Singapore, which is nearly on the equator, managed to contain coronavirus at first, but it has seen a growing outbreak recently. The problem, it seems, is the government neglected migrant workers in its initial response — letting Covid-19 spread in the cramped and sometimes unsanitary conditions many migrants live in. Warm, humid weather alone wasn’t enough to overcome preexisting issues and an overly narrow public policy response.

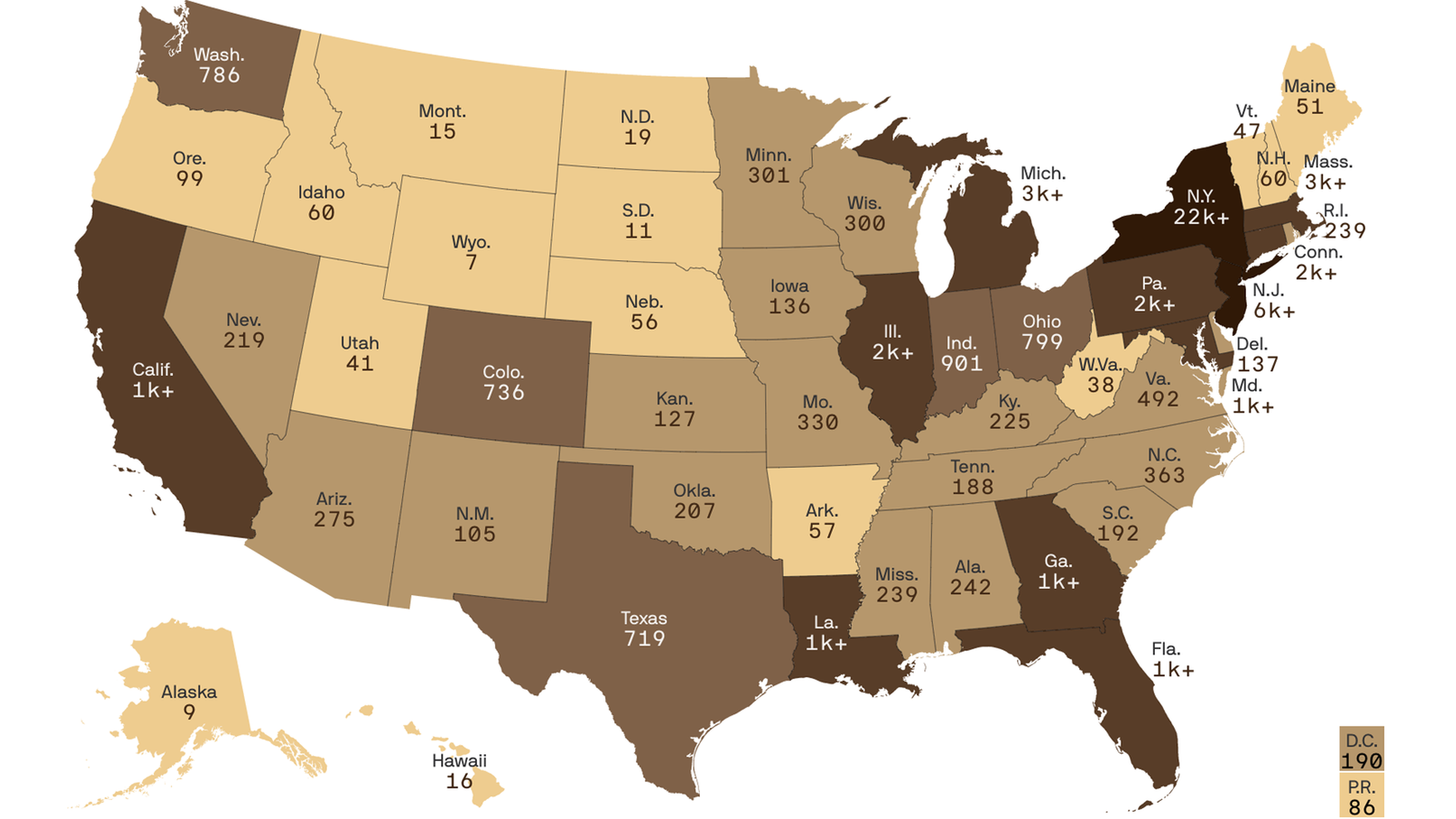

Meanwhile, Louisiana is suffering a significant coronavirus outbreak, with the fifth-most deaths per 100,000 people out of all the states. According to experts, Mardi Gras — held on February 25 — may have accelerated that. The massive celebration seemed to cause a lot of transmission, even as New Orleans saw temperatures up to the 70s, and cases continued to climb even as temperatures reached the 80s. Maybe the weather made things better than they would be otherwise, but it was, again, no match for human behavior’s effects on the spread of Covid-19.

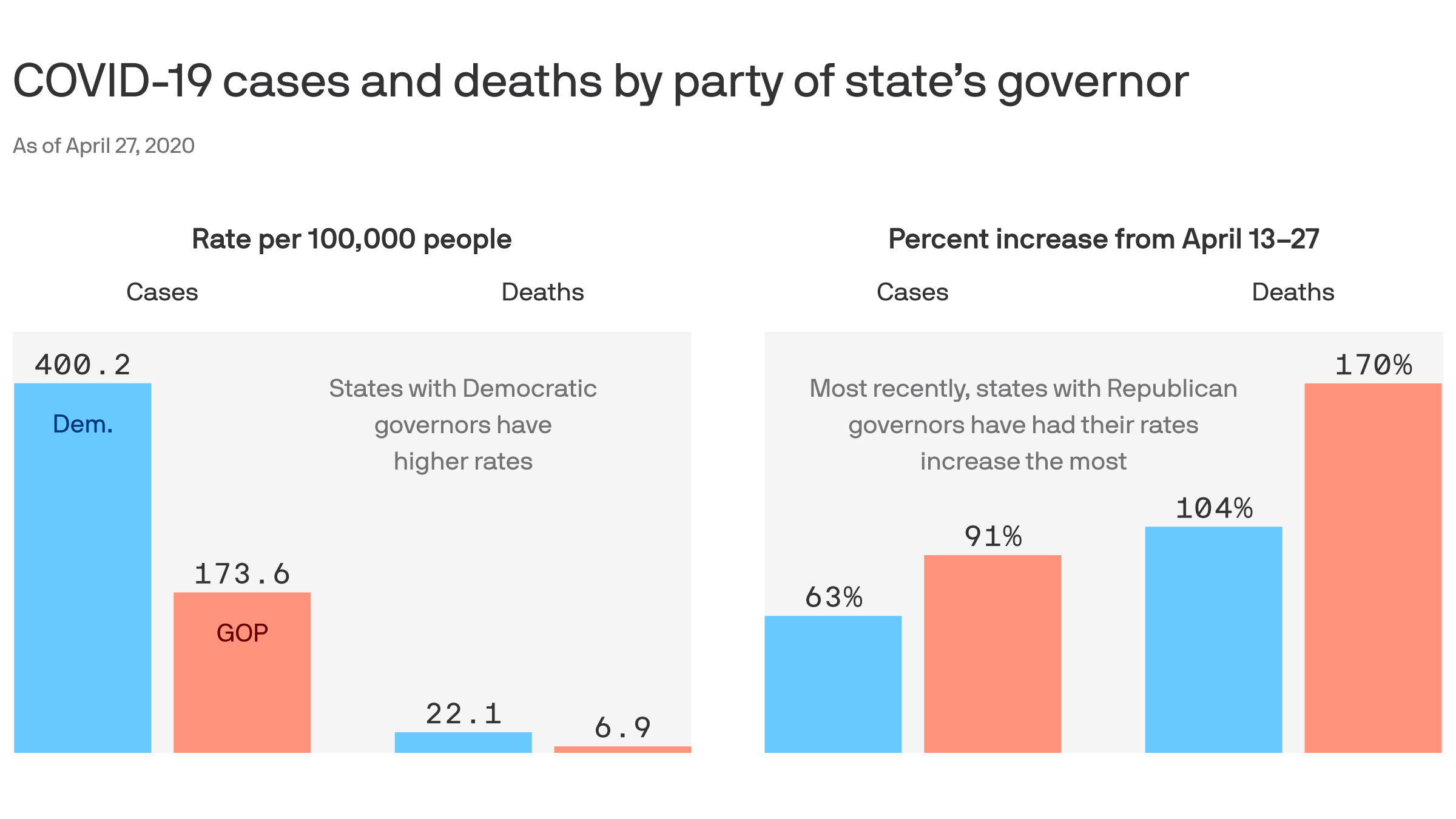

The bigger problem is too many people in the US are still vulnerable to the virus. “While we see some influence [of the weather], the effect that we’re seeing — if there’s any effect — is eclipsed by the high levels of susceptibility in the population,” Santillana said. “Most people are still highly susceptible. So even if temperature or humidity could play a role, there’s not enough immunity.”

That made it extremely easy for the virus to spread, regardless of the weather, especially since SARS-CoV-2 appears to be so contagious relative to other pathogens. In contrast, if you think about the viruses that are more affected by the seasons — the flu and colds — humans have been dealing with them for hundreds if not thousands of years. That’s let us build some population-level protection that we just don’t have for Covid-19, making other factors besides our actions, like the weather, a bit more important for the seasonal viruses.

So down the line, if Covid-19 becomes endemic — a possibility if, for example, immunity to it isn’t as permanent as we’d like — it’s possible that seasons will have a much stronger sway over when it pops up again.

Even then, it’s worth acknowledging that seasons don’t fully determine when the flu and colds hit. As the National Academies pointed out, some flu pandemics have started in the summer: “There have been 10 influenza pandemics in the past 250-plus years — two started in the northern hemisphere winter, three in the spring, two in the summer and three in the fall.”

In fact, some of this research could be taken to mean that coronavirus will be even more dangerous eventually: If the colder, dryer weather this fall and winter empowers the virus, that could lead to a bigger outbreak. The National Academies noted, as an example, that a second spike is typical for flu pandemics: “All had a peak second wave approximately six months after emergence of the virus in the human population, regardless of when the initial introduction occurred.”

But, as is true in the reverse, other factors besides the weather likely play a bigger role in the spread. So if governments and the public do the right thing through the fall and winter, there’s still a good chance that there won’t be a big spike.

Americans will likely be social distancing through the summer

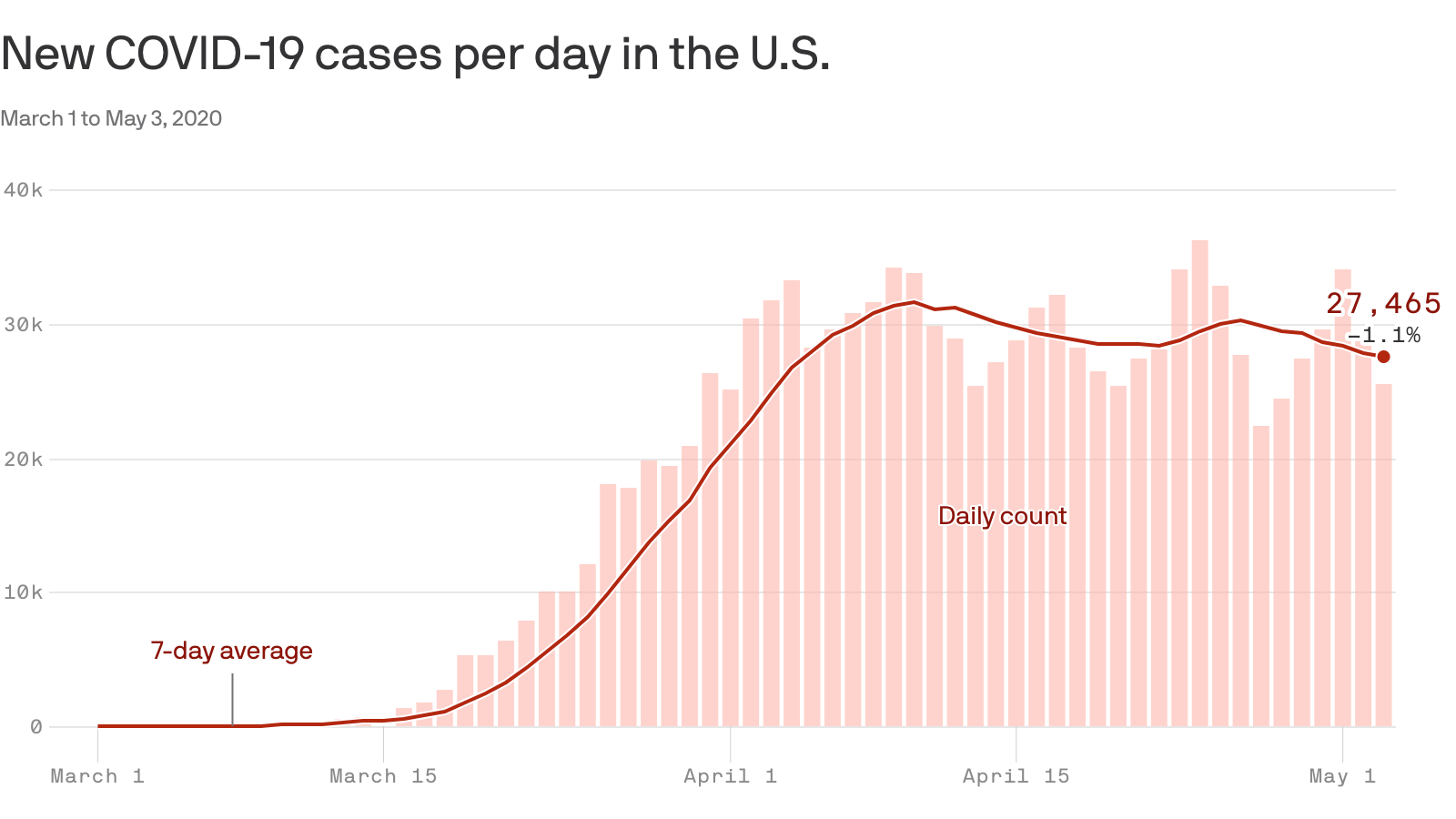

The upshot of all of this: The changing weather likely won’t be enough on its own to relax social distancing. Given that there’s still a lot about Covid-19 we still need to learn, experts don’t know this for certain. But it’s what they suspect, based on the data that we’ve seen in the research and real world so far.

“If the only concern is the health of people, it’s irresponsible to go back to relaxing social distancing anytime soon,” Santillana said. “We’re not done, even if summer starts.”

So as the plans to end social distancing indicate, the world will likely need at least some level of social distancing until a vaccine or a similarly effective medical treatment is developed, which is possibly a year or more away. That may not require the full lockdown that several states are seeing today, but it will mean restrictions on larger gatherings and some travel, while perhaps continuing remote learning and work.

Weather could help determine how safe it is to go outside, even as social distancing continues. Some states, for example, are considering opening parks and beaches during the earlier phases of reopening their economies. Experts warn that summer weather won’t allow large gatherings — 50 people or more is often cited as way too many — but it could give people some assurance that they can go outdoors as long as they keep 6 feet or more of distance from others they don’t live with, avoid touching surfaces and their faces, and wear masks.

Otherwise, however, how much social distancing will be relaxed in the coming months won’t come down to the weather but likely how much the US improves its testing and surveillance capacity. Testing gives officials the means to isolate sick people, track and quarantine the people whom those verified to be sick came into close contact with (a.k.a. contact tracing), and deploy community-wide efforts if a new cluster of cases is too large and uncontrolled otherwise.

While the US has seen some gains in testing, the number of new tests a day still fall below estimates of what’s needed (500,000 on the low end and tens of millions on the high end) to safely ease social distancing.

Along with testing, America will need aggressive contact tracing, as countries like South Korea and Germany have done, to control its outbreak. A report from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and Association of State and Territorial Health estimated the US will need to hire 100,000 contact tracers — far above what states and federal officials have so far said they’re hiring. A phone app could help mitigate the need for quite as many tracers, but it’s unclear if Americans have the appetite for an app that will effectively track their every move.

These are, really, the things everyone has been hearing about the entire time during this pandemic. It’s just worth emphasizing that the summer weather likely won’t be enough on its own to mitigate the need for these other public health strategies.

“The best-case scenario is if we’re doing that [social distancing] and there’s a dampening [in the summer], maybe there is a possibility of limiting this virus here in the United States and other places,” Jesse Bell, one of the University of Nebraska Medical Center researchers, told me. “But then again we just don’t know.”

So we’re very likely going to need social distancing, testing, and contact tracing for the foreseeable future, regardless of how warm, sunny, and humid it is outside.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19924839/GettyImages_1220238213.jpg)