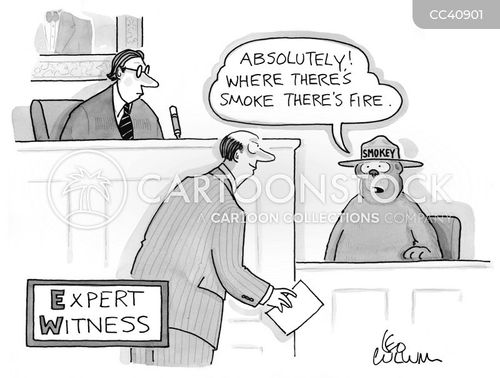

A pandemic would normally be a time when public health expertise and data are in urgent demand — yet President Trump and his administration have been going all out to undermine them.

Why it matters: There’s a new example almost every day of this administration trying to marginalize the experts and data that most administrations lean on and defer to in the middle of a global crisis.

Here’s how it has been happening just in the past few weeks:

- The administration has repeatedly undermined the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most recently, Trump has criticized the CDC’s school reopening guidelines, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos declared that “kids need to be in school,” and the administration has reportedly ordered hospitals to bypass the CDC in reporting coronavirus patient information.

- It has repeatedly undermined Anthony Fauci. Trump distanced himself on Wednesday from an op-ed attack by White House trade adviser Peter Navarro, but longtime Trump aide Dan Scavino also called the infectious diseases specialist “Dr. Faucet” in a Facebook post accusing him of leaking his disagreements. And the White House gave a opposition research-style list of the times Fauci “has been wrong” to the Washington Post and other media outlets.

- Trump himself undermined public health experts generally with his retweet of former game show host Chuck Woolery’s “everyone is lying” tweet — which blamed “The CDC, Media, Democrats, our Doctors, not all but most, that we are told to trust.”

- Trump has made numerous statements suggesting, over and over again, that we wouldn’t have as many COVID cases if we just tested less. (From his Tuesday press conference at the White House: “If we did half the testing we would have half the cases.”)

The impact: The result is that the CDC — which is supposed to be the go-to agency in a public health crisis — is distracted by constant public critiques from the highest levels. And Fauci, “America’s Doctor,” is the subject of yet another round of stories about whether Trump is freezing him out.

- “The way to make Americans safer is to build on, not bypass, our public health system,” Tom Frieden, a former CDC director under Barack Obama, said in a statement to Axios about the efforts to sideline the agency.

- “Unfortunately, as with mask-up recommendations and schools reopening guidance, the administration has chosen to sideline and undermine our nation’s premier disease fighting agency in the middle of the worst pandemic in 100 years,” Frieden said.

- And Fauci, in an interview with The Atlantic, said of the efforts to discredit him: “Ultimately, it hurts the president to do that … It doesn’t do anything but reflect poorly on them.”

The other side: The White House insists there’s no problem. “President Trump has always acted on the science and valued the input of public health experts throughout this crisis,” said White House deputy press secretary Sarah Matthews.

- Trump campaign communications director Tim Murtaugh closed ranks with the experts as well. “President Trump has said repeatedly that he has a strong relationship with Dr. Fauci, and Dr. Fauci has always said that the President listens to his advice,” he said.

- And Department of Health and Human Services spokesman Michael Caputo declared that “the scientists and doctors speak openly, they are listened to closely, and their advice and counsel helps guide the response.”

- “Frankly, when it comes to this tempest in a teapot over Dr. Fauci, I blame the media and their unending search for a ‘Resistance’ hero, for turning half a century of a brilliant scientist’s hard work into a clickbait headline that helps reporters undermine the president’s coronavirus response,” Caputo said.

Between the lines: Murtaugh deflected several times when asked whether there was a deliberate strategy to marginalize the CDC and the experts: “The President and the White House have consistently advised Americans to follow CDC guidelines. The President also believes we can open schools safely on time and that we must do so.”

- However, one administration official said there were parts of the CDC school reopening guidelines that were impractical, and noted that kids can also suffer long-term harm by staying out of school too long.

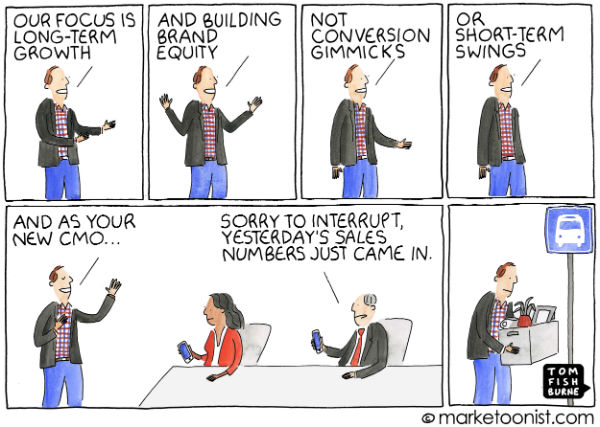

Our thought bubble, by Axios White House reporter Alayna Treene: The responses make it clear that the White House and the Trump campaign don’t want to advance the narrative that they’re deliberately battling with America’s health experts, or that there’s any kind of strategy behind it.

The bottom line: When the history of this pandemic is written, it will show that the public health experts who were trying to fight it also had to deal with political fights that made their jobs harder.