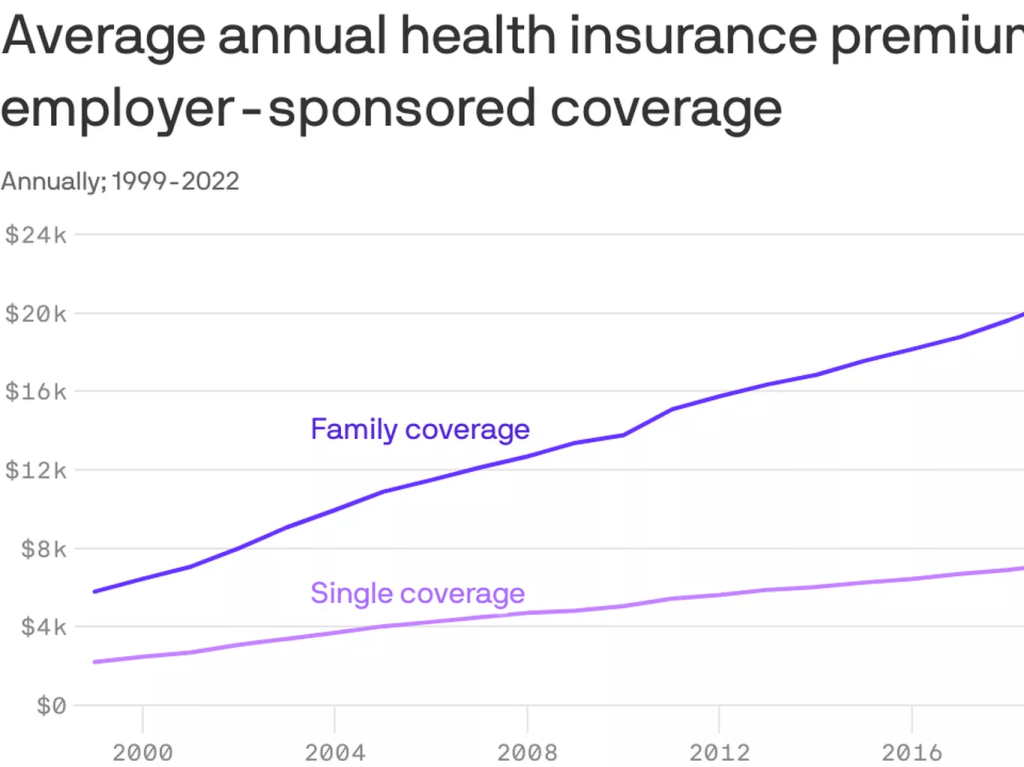

This year, 316 million Americans (92.3% of the population) have health insurance: 61 million are covered by Medicare, 79 million by Medicaid/CHIP and 164 million through employment-based coverage. By 2032, the Congressional Budget Office predicts Medicare coverage will increase 18%, Medicaid and CHIP by 0% and employer-based coverage will increase 3.0% to 169 million. For some in the industry, that justifies seating Medicare on the front row for attention. And, for many, it justifies leaving employers on the back bench since the working age population use hospitals, physicians and prescription meds less than seniors.

Last week, the Business Group on Health released its 2025 forecast for employer health costs based on responses from 125 primarily large employers surveyed in June: Highlights:

- “Since 2022, the projected increase in health care trend, before plan design changes, rose from 6% in 2022, 7.2% in 2024 to almost 8% for 2025. Even after plan design changes, actual health care costs continued to grow at a rate exceeding pre-pandemic increases. These increases point toward a more than 50% increase in health care cost since 2017. Moreover, this health care inflation is expected to persist and, in light of the already high burden of medical costs on the plan and employees, employers are preparing to absorb much of the increase as they have done in recent years.”.

- Per BGH, the estimated total cost of care per employee in 2024 is $18,639, up $1,438 from 2023. The estimated out-of-pocket cost for employees in 2024 is $1,825 (9.8%), compared to $1,831 (10.6%) in 2023.

The prior week, global benefits firm Aon released its 2025 assessment based on data from 950 employers:

- “The average cost of employer-sponsored health care coverage in the U.S. is expected to increase 9.0% surpassing $16,000 per employee in 2025–higher than the 6.4% increase to health care budgets that employers experienced from 2023 to 2024 after cost savings strategies. “

- On average, the total health-plan cost for employers increased 5.8% to $14,823 per employee from 2023 to 2024: employer costs increased 6.4% to 80.7% of total while employee premiums increased 3.4% increase–both higher than averages from the prior five years, when employer budgets grew an average of 4.4% per year and employees averaged 1.2% per year.

- Employee contributions in 2024 were $4,858 for health care coverage, of which $2,867 is paid in the form of premiums from pay checks and $1,991 is paid through plan design features such as deductibles, co-pays and co-insurance.

- The rate of health care cost increases varies by industry: technology and communications industry have the highest average employer cost increase at 7.4%, while the public sector has the highest average employee cost increase at 6.7%. The health care industry has the lowest average change in employee contributions, with no material change from 2023: +5.8%

And in July, PWC’s Health Research Institute released its forecast based on interviews with 20 health plan actuaries. Highlights:

- “PwC’s Health Research Institute (HRI) is projecting an 8% year-on-year medical cost trend in 2025 for the Group market and 7.5% for the Individual market. This near-record trend is driven by inflationary pressure, prescription drug spending and behavioral health utilization. The same inflationary pressure the healthcare industry has felt since 2022 is expected to persist into 2025, as providers look for margin growth and work to recoup rising operating expenses through health plan contracts. The costs of GLP-1 drugs are on a rising trajectory that impacts overall medical costs. Innovation in prescription drugs for chronic conditions and increasing use of behavioral health services are reaching a tipping point that will likely drive further cost inflation.”

Despite different methodologies, all three analyses conclude that employer health costs next year will increase 8-9%– well-above the Congressional Budget Office’ 2025 projected inflation rate (2.2%), GDP growth (2.4% and wage growth (2.0%). And it’s the largest one-year increase since 2017 coming at a delicate time for employers worried already about interest rates, workforce availability and the political landscape.

For employers, the playbook has been relatively straightforward: control health costs through benefits designs that drive smarter purchases and eliminate unnecessary services. Narrow networks, price transparency, on-site/near-site primary care, restrictive formularies, value-based design, risk-sharing contracts with insurers and more have become staples for employers.

But this playbook is not working for employers: the intrinsic economics of supply-driven demand and its regulated protections mitigate otherwise effective ways to lower their costs while improving care for their employees and families.

My take:

Last week, I reviewed the healthcare advocacy platforms for the leading trade groups that represent employers in DC and statehouses to see what they’re saying about their take on the healthcare industry and how they’re leaning on employee health benefits. My review included the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, National Federal of Independent Businesses, Business Roundtable, National Alliance of Purchaser Coalitions, Purchaser Business Group on Health, American Benefits Council, Self-Insurance Institute of America and the National Association of Manufacturers.

What I found was amazing unanimity around 6 themes:

- Providing health benefits to employees is important to employers. Protecting their tax exemptions, opposing government mandates, and advocating against disruptive regulations that constrain employer-employee relationships are key.

- Healthcare affordability is an issue to employers and to their employees, All see increasing insurance premiums, benefits design changes, surprise bills, opaque pricing, and employee out-of-pocket cost obligations as problems.

- All believe their members unwillingly subsidize the system paying 1.6-2.5 times more than what Medicare pays for the same services. They think the majority of profits made by drug companies, hospitals, physicians, device makers and insurers are the direct result of their overpayments and price gauging.

- All think the system is wasteful, inefficient and self-serving. Profits in healthcare are protected by regulatory protections that disable competition and consumer choices.

- All think fee-for-service incentives should be replaced by value-based purchasing.

- And all are worried about the obesity epidemic (123 million Americans) and its costs-especially the high-priced drugs used in its treatment. It’s the near and present danger on every employer’s list of concerns.

This consensus among employers and their advocates is a force to be reckoned. It is not the same voice as health insurers: their complicity in the system’s issues of affordability and accountability is recognized by employers. Nor is it a voice of revolution: transformational changes employers seek are fixes to a private system involving incentives, price transparency, competition, consumerism and more.

Employers have been seated on healthcare’s back bench since the birth of the Medicare and Medicaid programs in 1965. Congress argues about Medicare and Medicaid funding and its use. Hospitals complain about Medicare underpayments while marking up what’s charged employers to make up the difference. Drug companies use a complicated scheme of patents, approvals and distribution schemes to price their products at will presuming employers will go along. Employers watched but from the back row.

As a new administration is seated in the White House next year regardless of the winner, what’s certain is healthcare will get more attention, and alongside the role played by employers. Inequities based on income, age and location in the current employer-sponsored system will be exposed. The epidemic of obesity and un-attended demand for mental health will be addressed early on. Concepts of competition, consumer choice, value and price transparency will be re-defined and refreshed. And employers will be on the front row to make sure they are.

For employers, it’s crunch time: managing through the pandemic presented unusual challenges but the biggest is ahead. Of the 18 benefits accounted as part of total compensation, employee health insurance coverage is one of the 3 most expensive (along with paid leave and Social Security) and is the fastest growing cost for employers. Little wonder, employers are moving from the back bench to the front row.