The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention abruptly changed its recommendations, saying people without Covid-19 symptoms should not get tested.

Trump administration officials on Wednesday defended a new recommendation that people without Covid-19 symptoms abstain from testing, even as scientists warned that the policy could hobble an already weak federal response as schools reopen and a potential autumn wave looms.

The day after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued the revised guidance, there were conflicting reports on who was responsible. Two federal health officials said the shift came as a directive to the Atlanta-based C.D.C. from higher-ups in Washington at the White House and the Department of Health and Human Services.

Adm. Brett P. Giroir, the administration’s coronavirus testing czar, called it a “C.D.C. action,” written with input from the agency’s director, Dr. Robert R. Redfield. But he acknowledged that the revision came after a vigorous debate among members of the White House coronavirus task force — including its newest member, Dr. Scott W. Atlas, a frequent Fox News guest and a special adviser to President Trump.

“We all signed off on it, the docs, before it ever got to a place where the political leadership would have, you know, even seen it, and this document was approved by the task force by consensus,” Dr. Giroir said. “There was no weight on the scales by the president or the vice president or Secretary Azar,” he added, referring to Alex M. Azar II, the secretary of health and human services.

Regardless of who is responsible, the shift is highly significant, running counter to scientific evidence that people without symptoms could be the most prolific spreaders of the coronavirus. And it comes at a very precarious moment. Hundreds of thousands of college and K-12 students are heading back to campus, and broad testing regimens are central to many of their schools’ plans. Businesses are reopening, and scientists inside and outside the administration are growing concerned about political interference in scientific decisions.

Democratic governors who were weighing how to keep the virus contained as their economies and schools come to life said limiting testing for asymptomatic citizens would make the task impossible.

“The only plausible rationale,” Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo of New York told reporters in a conference call from Albany, N.Y., “is that they want fewer people taking tests, because as the president has said, if we don’t take tests, you won’t know the number of people who are Covid-positive.”

Over the weekend, the Food and Drug Administration, under pressure from Mr. Trump, gave emergency approval to expand the use of antibody-rich blood plasma to treat Covid-19 patients. The move came just days after scientists, including Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, and Dr. Francis S. Collins, the director of the National Institutes of Health, intervened to stop the practice because of lack of evidence that it worked.

The move echoed a decision by the Food and Drug Administration to grant an emergency use waiver for hydroxychloroquine, a malaria drug repeatedly sold by Mr. Trump as a treatment for Covid-19. The agency revoked the waiver in June, when clinical trials suggested the drug’s risks outweighed any possible benefits.

The testing shift, experts say, was a far more puzzling reversal. Dr. Giroir said the move was “discussed extensively by” members of the White House coronavirus task force, and he named Dr. Redfield, Dr. Atlas, Dr. Fauci and Dr. Stephen M. Hahn, the commissioner of food and drugs. Notably, he did not name Dr. Deborah L. Birx, the White House coronavirus response coordinator. But he said Dr. Fauci was among those who had “signed off.”

In a brief interview, Dr. Fauci said he had seen an early iteration of the guidelines and did not object. But the final debate over the revisions took place at a task force meeting on Thursday, when Dr. Fauci was having surgery under general anesthesia to remove a polyp on his vocal cord. In retrospect, he said, he now had “some concerns” about advising people against getting tested, because the virus could be spread through asymptomatic contact.

“My concern is that it will be misinterpreted,” Dr. Fauci said.

The newest version of the C.D.C. guidelines, posted on Monday, amended the agency’s guidance to say that people who had been in close contact with an infected individual — typically defined as being within six feet of a person with the coronavirus and for at least 15 minutes — “do not necessarily need a test” if they do not have symptoms.

Exceptions might be made for “vulnerable” individuals, the agency noted, or if health care providers or state or local public health officials recommended testing.

Dr. Giroir said the new recommendation matched existing guidance for hospital workers and others in frontline jobs who have “close exposures” to people infected with the coronavirus. Such workers are advised to take proper precautions, like wearing masks, socially distancing, washing their hands frequently and monitoring themselves for symptoms.

He argued that testing those exposed to the virus was of little utility, because tests capture only a single point in time, and that the results could give people a false sense of security.

“A negative test on Day 2 doesn’t mean you’re negative. So what is the value of that?” Dr. Giroir asked, adding, “It doesn’t mean on Day 4 you can go out and visit Grandma or on Day 6 go out without a mask on in school.”

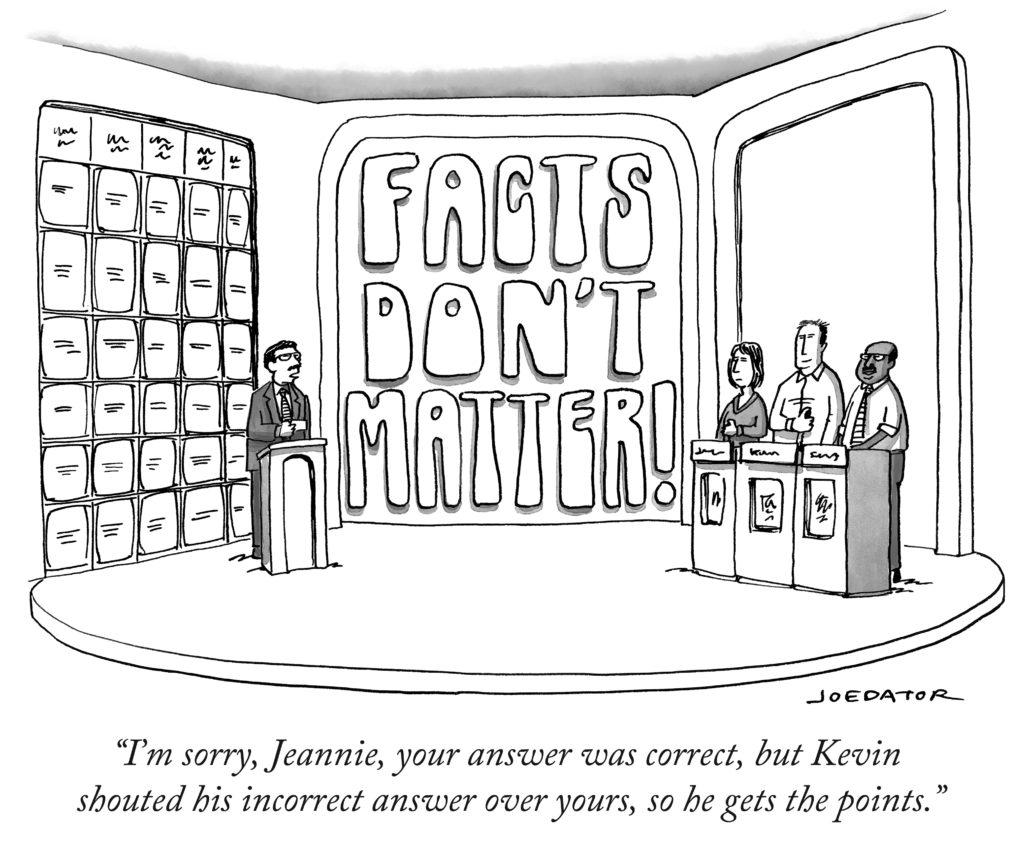

The guidelines come amid growing concern that the C.D.C., the agency charged with tracking and fighting outbreaks of infectious disease, is being sidelined by its parent agency, the Department of Health and Human Services, and the White House. Under ordinary circumstances, administering public health advice to the nation would fall squarely within the C.D.C.’s portfolio.

Experts have called the revisions alarming and dangerous, noting that the United States needs more testing, not less. And they have expressed deep concern that the C.D.C. is posting guidelines that its own officials did not author. A former C.D.C. director, Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, railed against the move on Twitter on Wednesday:

Later, in an interview, Dr. Frieden elaborated. He noted that the C.D.C. had recently dropped its recommendation that people quarantine for 14 days after traveling from an area with a high number of cases to one where the virus was less prevalent. And he reiterated that testing the contacts of those infected was an important means of curbing the spread of the virus.

“We don’t know the best protocol for testing of contacts: Should you test all contacts? That’s the kind of study that frankly needs to get done,” Dr. Frieden said. But absent the answer to that question, he added, “I certainly wouldn’t say, ‘Don’t test contacts.’”

Democrats, including Speaker Nancy Pelosi and two governors — Mr. Cuomo and Gavin Newsom of California — were outraged by the changes. Mr. Newsom said California would not follow the new guidelines, and Mr. Cuomo blamed Mr. Trump.

Representative Frank Pallone Jr. of New Jersey, a Democrat and the chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, also chimed in on Twitter: “The Trump Admin has a lot of explaining to do. #COVID19 testing is essential to stopping the spread of the pandemic. I’m concerned that CDC is once again caving to political pressure. This simply cannot stand.”

Mr. Trump has suggested that the nation should do less testing, arguing that administering more tests was driving up case numbers and making the United States look bad. But experts say the true measure of the pandemic is not case numbers but test positivity rates — the percentage of tests coming back positive.

As Dr. Giroir denied that politics was involved, he encouraged the continued testing of asymptomatic people for surveillance purposes — to determine the prevalence of the virus in a given community — and said such “baseline surveillance testing” would still be appropriate in schools and on college campuses.

“We’re trying to do appropriate testing, not less testing,” he said.

Still, the revisions left many public health officials scratching their heads. They might have made sense when the United States was experiencing a shortage of tests, some experts said, but that no longer appears to be the case. Dr. Frieden, however, said it was possible the administration was trying to conserve testing in case of another surge.

“The problem is we have too many cases, so there is basically no way to keep up the testing if you have a huge outbreak,” he said.

Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said she was “not as up in arms about the content of the guidelines” as she was about the idea that the C.D.C.’s own experts did not write them — and that C.D.C. officials were referring all questions about them to the health department in Washington.

“These guidelines are clearly controversial, and many are calling on C.D.C. to explain its rationale for them, but C.D.C. is unable to comment,” she said in an email. “This is really dangerous precedent, and I fear it will erode public trust in C.D.C.”