Cartoon – Adding Injury to Insult

Average benchmark premiums for plans on the Affordable Care Act’s exchanges have fallen for the third straight year, according to a new analysis.

Researchers at the Urban Institute, a left-leaning think tank, found that the average benchmark premium on the exchanges fell by 1.7% for 2021. That follows decreases of 1.2% in 2019 and 3.2% in 2020.

By contrast, premiums for employer-sponsored plans increased by 4% in both 2019 and 2020, according to the report. Data for 2021 on the employer market are not yet available, the researchers said.

The national average benchmark premium was $443 per month for a 40-year-old nonsmoker, according to the report, before accounting for any tax credits.

The researchers found much significant variation in premium levels between states, though the difference in growth rates was smaller. Minnesota reported the lowest average benchmark premium at $292 per month, and the highest was in Wisconsin at $782 per month.

Average benchmark premiums topped $500 in 10 states, according to the report.

One of the key trends that’s slowing premium growth is increasing competition in the exchanges, as many insurers are expanding their offerings or returning to the marketplaces to offer plans, according to the report.

“New entrants included national and regional insurers, Medicaid insurers, and small start-up insurers,” the researchers wrote.

“Medicaid insurers are those who operated exclusively in the Medicaid managed-care market before 2014; they have increased their participation in the Marketplaces over time. Medicaid insurers are experienced in establishing narrow, low-cost provider networks that allow them to offer lower premiums than other insurers.”

UnitedHealthcare, for example, participated in just four regions included in the study in 2017, but had upped its participation to 11 for 2021. Aetna participated in three regions included in the study in 2017 before fully exiting the exchanges; CVS Health CEO Karen Lynch told investors earlier this year that the insurer plans to return to the marketplaces in 2022.

Several states have also launched programs that aim to lower premiums, according to the report. These include reinsurance programs, which have been rolled out in 12 states as of this year. Some states have also expanded Medicaid in recent years, which leads to some low-income people with costly health needs switching to that program, the researchers said.

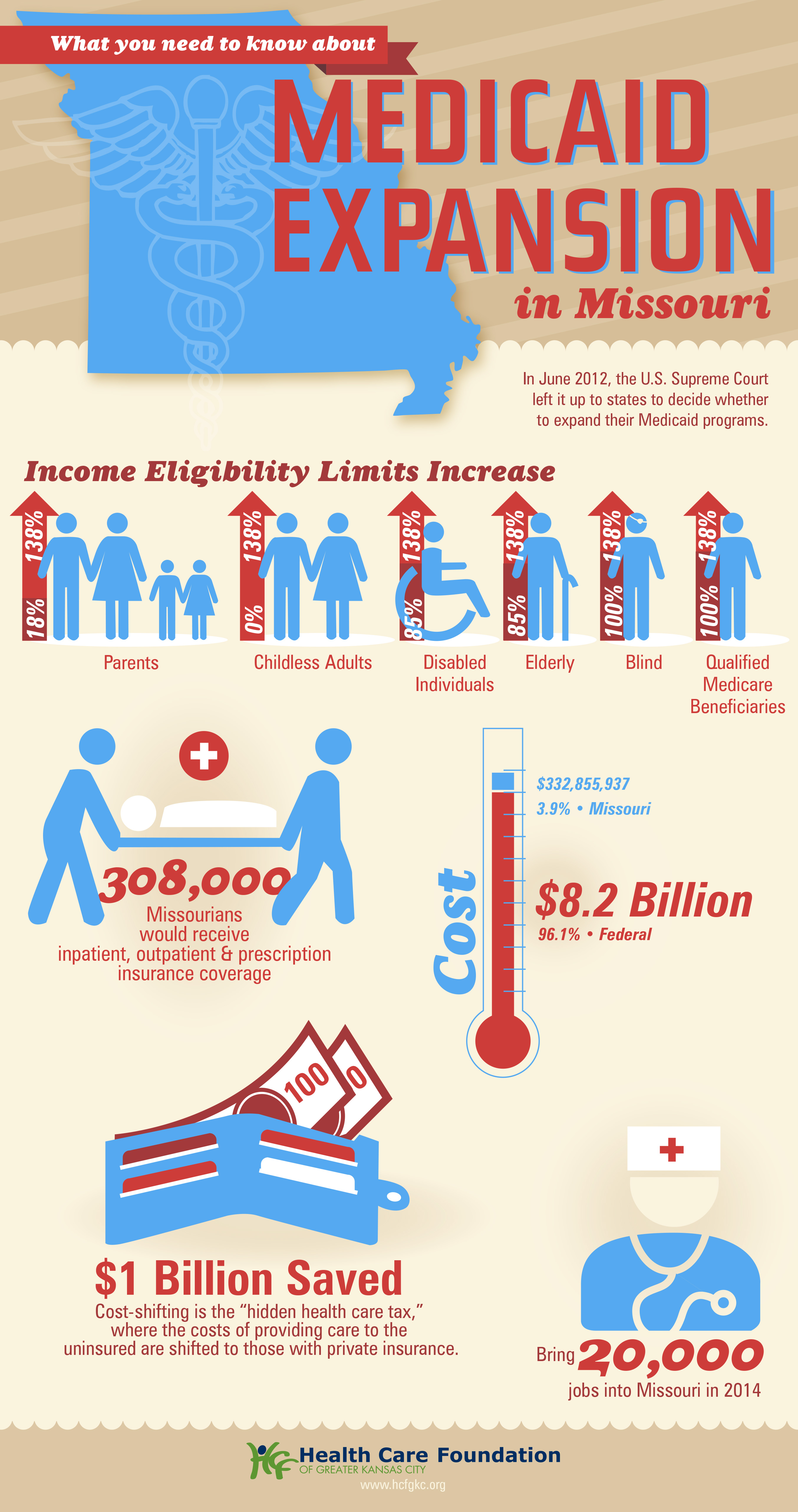

Missouri Gov. Mike Parson announced Thursday that his state would not expand Medicaid coverage to 275,000 residents who will become eligible on July 1st, despite a 2020 ballot initiative in which a majority of the state’s voters approved the expansion. Because the Missouri legislature has blocked funding for the expansion, Parson declared that the state’s Medicaid program, MO HealthNet, would run out of money if it moved forward.

The legislature’s decision to block funding was bolstered by an appeals court opinion last year, which challenged the expansion because the ballot initiative did not include a funding mechanism for widening coverage.

Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the federal government would have picked up 90 percent of the cost of expanding Medicaid in the state, in addition to boosting funding for existing Medicaid enrollees by 5 percent, thanks to a measure in the recent American Rescue Plan Act.

The governor’s decision leaves in place one of the strictest Medicaid eligibility standards in the nation: a family of three in Missouri must earn less than 21 percent of the federal poverty level—$5,400 per year—in order to qualify for coverage. The expansion measure would have opened the program to childless adults, and raised the eligibility limit to 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

The Missouri Hospital Association called the decision an “affront” to voters, pointing out that the state is currently running a budget surplus, and could easily allocate funds for the expansion. The status of Medicaid expansion in Missouri, which would become the 38th state to undertake expansion since the ACA’s passage, will ultimately be decided by court ruling, according to observers.

Meanwhile, like other states (mostly in the Southeast) that have resisted Medicaid expansion, Missouri will continue to see tax dollars flow out of the state to fund benefits in states that have expanded eligibility—despite the express will of voters. Given ample evidence that Medicaid expansion boosts access to care, health status, and health system sustainability, it’s nearly unfathomable that the politics of “Obamacare” continue to complicate the extension of this critical safety-net program.

https://mailchi.mp/097beec6499c/the-weekly-gist-april-30-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

We’ve closely tracked Colorado’s pursuit of its own public option insurance plan, which seems now to have reached a compromise that will allow a bill to move forward, according to reporting from Colorado Public Radio. The saga began two years ago when state legislators passed a law requiring Democratic Governor Jared Polis’ administration to develop a public option proposal. Amid the pandemic and broad industry opposition, progress stalled last year on the proposal. Lawmakers picked up the proposal this session, and have made progress on a compromise bill now poised to pass the state’s Democratic legislature.

Unlike the earlier version, the new legislation would not lay the groundwork for a government-run insurance option, but rather would force insurers to offer a plan in which the benefits and premiums are defined and regulated by the state. The bill would also allow the state to regulate how much hospitals and doctors are paid.

In the current version, hospital reimbursement is set at a minimum of 155 percent of Medicare rates, and premiums are expected to be 18 percent lower than the current average. While state Republicans and some progressive Democrats are still opposed, the Colorado Hospital Association and State Association of Health Plans are neutral on the bill, largely eliminating industry opposition.

The role hospitals played in fighting the pandemic surely paved the way toward the compromise bill, which is viewed as much more friendly to providers than the previous proposal. With the Biden administration unlikely to pursue Medicare expansion or a national public option, we expect more Democratic-run states to pursue these sorts of state-level efforts to expand coverage.

In the wake of the pandemic, providers are well-positioned to negotiate—and should use the goodwill they’ve generated to explore more favorable terms, rather than resorting to their usual knee-jerk opposition to these kinds of proposals.

https://mailchi.mp/097beec6499c/the-weekly-gist-april-30-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

In his first address to a joint session of Congress, delivered on the eve of his 100th day in office, President Biden laid out his vision for two major legislative proposals to follow the $1.9T stimulus package he signed into law last month.

The first, described as an “infrastructure” bill, focuses largely on investing in transportation-related improvements, building projects, and “green” upgrades to the nation’s energy grid, along with a $400B investment in home-based care for the elderly and people with disabilities—which amounts to over 17 percent of the package’s $2.3T price tag.

The second, which he unveiled in Wednesday’s speech, is a $1.8T “families” bill, is largely aimed at expanding childcare subsidies, early childhood education, paid family and medical leave, and educational investments. Included in that package is $200B to extend the temporary subsidies—approved as part of last month’s stimulus law—for those seeking health insurance coverage on the individual marketplaces created by the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Notably absent from either proposal were two categories of healthcare reform that received much focus and airtime during last year’s election campaign: reducing the cost of prescription drugs and lowering the eligibility age for Medicare to 60 or below. Given the closely divided makeup of the new Congress, and the relatively moderate position staked out by the Biden administration on healthcare issues (with a bias toward bolstering the ACA rather than pursuing sweeping changes), we’re not surprised to see the Medicare expansion go unmentioned.

But the bipartisan popularity of lowering prescription drug costs seems like a missed opportunity for Biden, who encouraged the Congress to return to it separately, later in the year. We’ll see. For now, with even some Democrats expressing concern about the $4.1T price tag of Biden’s proposals, we would be surprised if all $600B of the healthcare-related spending makes it to the final legislation. In particular, our guess is that some portion of the home-care spending will get traded away in favor of other components of the package. Expect negotiations to be intense.