Cartoon – State of the Union (Underinsured)

The complexity of Medicare Advantage (MA) physician networks has been well-documented, but the payment regulations that underlie these plans remain opaque, even to experts. If an MA plan enrollee sees an out-of-network doctor, how much should she expect to pay?

The answer, like much of the American healthcare system, is complicated. We’ve consulted experts and scoured nearly inscrutable government documents to try to find it. In this post we try to explain what we’ve learned in a much more accessible way.

Medicare Advantage Basics

Medicare Advantage is the private insurance alternative to traditional Medicare (TM), comprised largely of HMO and PPO options. One-third of the 60+ million Americans covered by Medicare are enrolled in MA plans. These plans, subsidized by the government, are governed by Medicare rules, but, within certain limits, are able to set their own premiums, deductibles, and service payment schedules each year.

Critically, they also determine their own network extent, choosing which physicians are in- or out-of-network. Apart from cost sharing or deductibles, the cost of care from providers that are in-network is covered by the plan. However, if an enrollee seeks care from a provider who is outside of their plan’s network, what the cost is and who bears it is much more complex.

Provider Types

To understand the MA (and enrollee) payment-to-provider pipeline, we first need to understand the types of providers that exist within the Medicare system.

Participating providers, which constitute about 97% of all physicians in the U.S., accept Medicare Fee-For-Service (FFS) rates for full payment of their services. These are the rates paid by TM. These doctors are subject to the fee schedules and regulations established by Medicare and MA plans.

Non-participating providers (about 2% of practicing physicians) can accept FFS Medicare rates for full payment if they wish (a.k.a., “take assignment”), but they generally don’t do so. When they don’t take assignment on a particular case, these providers are not limited to charging FFS rates.

Opt-out providers don’t accept Medicare FFS payment under any circumstances. These providers, constituting only 1% of practicing physicians, can set their own charges for services and require payment directly from the patient. (Many psychiatrists fall into this category: they make up 42% of all opt-out providers. This is particularly concerning in light of studies suggesting increased rates of anxiety and depression among adults as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic).

How Out-of-Network Doctors are Paid

So, if an MA beneficiary goes to see an out-of-network doctor, by whom does the doctor get paid and how much? At the most basic level, when a Medicare Advantage HMO member willingly seeks care from an out-of-network provider, the member assumes full liability for payment. That is, neither the HMO plan nor TM will pay for services when an MA member goes out-of-network.

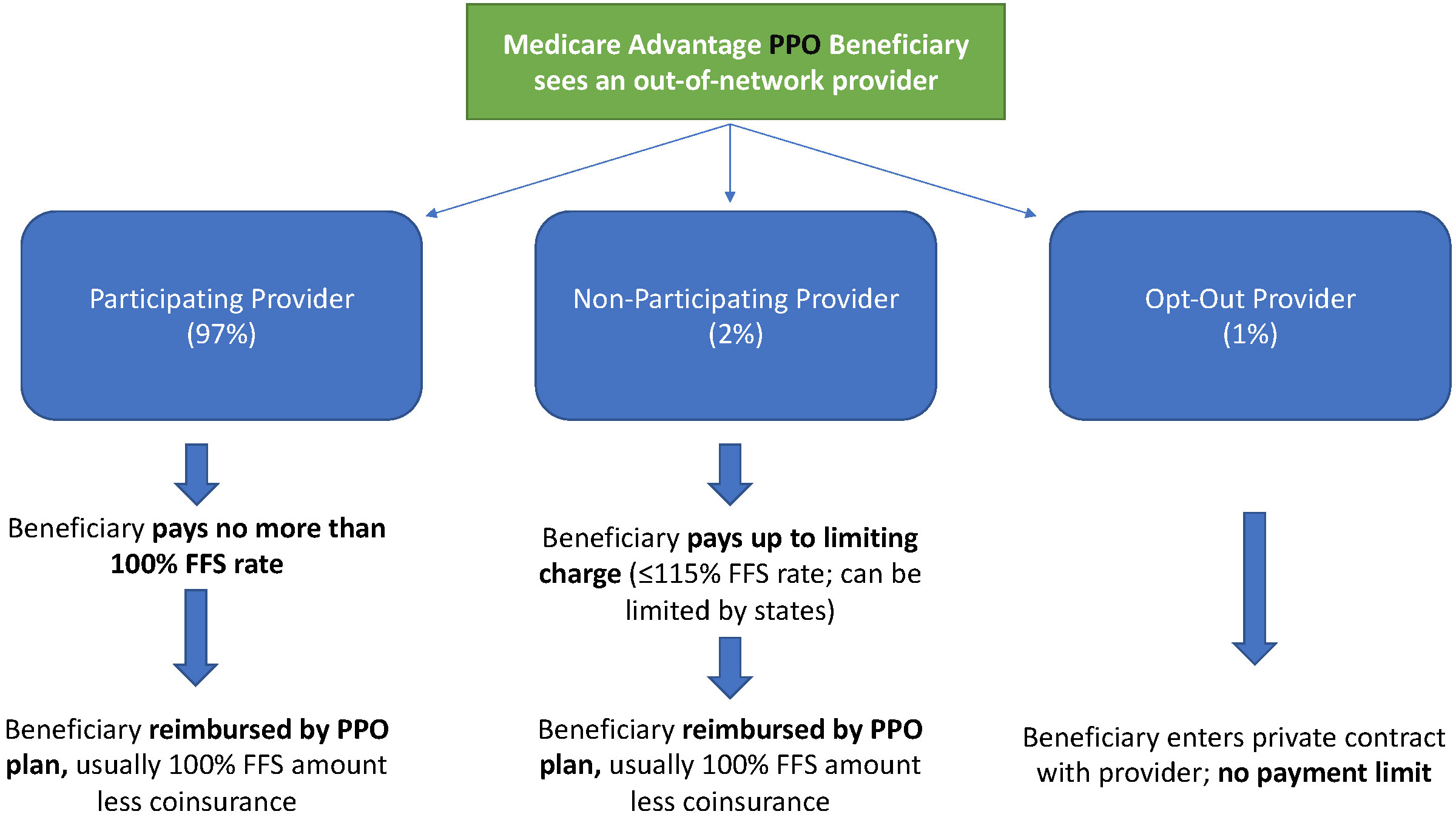

The price that the provider can charge for these services, though, varies, and must be disclosed to the patient before any services are administered. If the provider is participating with Medicare (in the sense defined above), they charge the patient no more than the standard Medicare FFS rate for their services. Non-participating providers that do not take assignment on the claim are limited to charging the beneficiary 115% of the Medicare FFS amount, the “limiting charge.” (Some states further restrict this. In New York State, for instance, the maximum is 105% of Medicare FFS payment.) In these cases, the provider charges the patient directly, and they are responsible for the entire amount (See Figure 1.)

Alternatively, if the provider has opted-out of Medicare, there are no limits to what they can charge for their services. The provider and patient enter into a private contract; the patient agrees to pay the full amount, out of pocket, for all services.

MA PPO plans operate slightly differently. By nature of the PPO plan, there are built-in benefits covering visits to out-of-network physicians (usually at the expense of higher annual deductibles and co-insurance compared to HMO plans). Like with HMO enrollees, an out-of-network Medicare-participating physician will charge the PPO enrollee no more than the standard FFS rate for their services. The PPO plan will then reimburse the enrollee 100% of this rate, less coinsurance. (See Figure 2.)

In contrast, a non-participating physician that does not take assignment is limited to charging a PPO enrollee 115% of the Medicare FFS amount, which can be further limited by state regulations. In this case, the PPO enrollee is also reimbursed by their plan up to 100% (less coinsurance) of the FFS amount for their visit. Again, opt-out physicians are exempt from these regulations and must enter private contracts with patients.

Some Caveats

There are two major caveats to these payment schemes (with many more nuanced and less-frequent exceptions detailed here). First, if a beneficiary seeks urgent or emergent care (as defined by Medicare) and the provider happens to be out-of-network for the MA plan (regardless of HMO/PPO status), the plan must cover the services at their established in-network emergency services rates.

The second caveat is in regard to the declared public health emergency due to COVID-19 (set to expire in April 2021, but likely to be extended). MA plans are currently required to cover all out-of-network services from providers that contract with Medicare (i.e., all but opt-out providers) and charge beneficiaries no more than the plan-established in-network rates for these services. This is being mandated by CMS to compensate for practice closures and other difficulties of finding in-network care as a result of the pandemic.

Conclusion

Outside of the pandemic and emergency situations, knowing how much you’ll need to pay for out-of-network services as a MA enrollee depends on a multitude of factors. Though the vast majority of American physicians contract with Medicare, the intersection of insurer-engineered physician networks and the complex MA payment system could lead to significant unexpected costs to the patient.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) made historic strides in expanding access to health insurance coverage by covering an additional 20 million Americans. President Joe Biden ran on a platform of building upon the ACA and filling in its gaps. With Democratic majority in the Senate, aspects of his health care plan could move from idea into reality.

The administration’s main focus is on uninsurance, which President Biden proposes to tackle in three main ways: providing an accessible and affordable public option, increasing tax credits to help lower monthly premiums, and indexing marketplace tax credits to gold rather than silver plans.

However, underinsurance remains a problem. Besides the nearly 29 million remaining uninsured Americans, over 40% of working age adults are underinsured, meaning their out-of-pocket cost-sharing, excluding premiums, are 5-10% of household income or more, depending on income level.

High cost-sharing obligations—especially high deductibles—means insurance might provide little financial protection against medical costs beneath the deductible. Bills for several thousand dollars could financially devastate a family, with the insurer owing nothing at all. Recent trends in health insurance enrollment suggest that uninsurance should not be the only issue to address.

A high demand for low premiums

Enrollment in high deductible health plans (HDHP) has been on a meteoric rise over the past 15 years, from approximately 4% of people with employer-sponsored insurance in 2006 to nearly 30% in 2019, leading to growing concern about underinsurance. “Qualified” HDHPs, which come with additional tax benefits, generally have lower monthly premiums, but high minimum deductibles. As of 2020, the Internal Revenue Service defines HDHPs as plans with minimum deductibles of at least $1,400 for an individual ($2,800 for families), although average annual deductibles are $2,583 for an individual ($5,335 for families).

HDHPs are associated with delays in both unnecessary and necessary care, including cancer screenings and treatment, or skipped prescription fills. There is evidence that Black patients disproportionately experience these effects, which may further widen racial health inequities.

A common prescription has been to expand access to Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), with employer and individual contributions offsetting higher upfront cost-sharing. Employers often contribute on behalf of their employees to HSAs, but for individuals in lower wage jobs without such benefits or without extra income to contribute themselves, the account itself may sit empty, rendering it useless.

A recent article in Health Affairs found that HDHP enrollment increased from 2007 to 2018 across all racial, ethnic, and income groups, but also revealed that low-income, Black, and Hispanic enrollees were significantly less likely to have an HSA, with disparities growing over time. For instance, by 2018, they found that among HDHP enrollees under 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL), only 21% had an HSA, while 52% of those over 400% FPL had an HSA. In short, the people who could most likely benefit from an HSA were also least likely to have one.

If trends in HDHP enrollment and HSA access continue, it could result in even more Americans who are covered on paper, yet potentially unable to afford care.

Addressing uninsurance could also begin to address underinsurance

President Biden’s health care proposal primarily addresses uninsurance by making it more affordable and accessible. This can also tangentially tackle underinsurance.

To make individual market insurance more affordable, Biden proposes expanding the tax credits established under the ACA. His plan calls for removing the 400% FPL cap on financial assistance in the marketplaces and lowering the limit on health insurance premiums to 8.5% of income. Americans would now be able to opt out of their employer plan if there is a better deal on HealthCare.gov or their state Marketplace. Previously, most individuals who had an offer of employer coverage were ineligible for premium subsidies—important for individuals whose only option might have been an employer-sponsored HDHP.

Biden also proposes to index the tax credits that subsidize premiums to gold plans, rather than silver plans as currently done. This would increase the size of these tax credits, making it easier for Americans to afford more generous plans with lower deductibles and out-of-pocket costs, substantially reducing underinsurance.

The most ambitious of Biden’s proposed health policies is a public option, which would create a Medicare-esque offering on marketplaces, available to anyone. As conceived in Biden’s proposal, such a plan would eliminate premiums and having minimal-to-no cost-sharing for low-income enrollees; especially meaningful for under- and uninsured people in states yet to expand Medicaid.

Moving forward: A need to directly address underinsurance

More extensive efforts are necessary to meaningfully address underinsurance and related inequities. For instance, the majority of persons with HDHPs receive coverage through an employer, where the employer shares in paying premiums, yet cost-sharing does not adjust with income as it can in the marketplace. Possible solutions range from employer incentives to expanding the scope of deductible-exempt services, which could also address some of the underlying disparities that affect access to and use of health care.

The burden of high cost-sharing often falls on those who cannot afford it, while benefiting employers, healthy employees, or those who can afford large deductibles. Instead of encouraging HSAs, offering greater pre-tax incentives that encourage employers to reabsorb some of the costs that they have shifted on their lower-income employees could prevent the income inequity gap from widening further.

Under the ACA, most health insurance plans are required to cover certain preventative services without patient cost-sharing. Many health plans also exempt other types of services from the deductible – from generic drugs to certain types of specialist visits – although these exemptions vary widely across plans. Expanding deductible-exempt services to include follow-up care or other high-value services could improve access to important services or even medication adherence without high patient cost burden. Better educating employees about what services are exempt would make sure that patients aren’t forgoing care that should be fully covered.

Health insurance is complicated. Choosing a plan is only the start. More affordable choices are helpful only if these choices are fully understood, e.g., the tradeoff between an HDHP’s lower monthly premium and the large upfront out-of-pocket cost when using care. Investing in well-trained, diverse navigators to help people understand how their options work with their budget and health care needs can make a big difference, given that low health insurance literacy is related to higher avoidance of care.

The ACA helped expand coverage, but now it’s time to make sure the coverage provided is more than an unused insurance card. The Biden administration has the opportunity and responsibility to make progress not only on reducing the uninsured rate, but also in reducing disparities in access and patient affordability.

President Joe Biden has an unexpected opening to cut deals with red states to expand Medicaid, raising the prospect that the new administration could extend health protections to millions of uninsured Americans and reach a goal that has eluded Democrats for a decade.

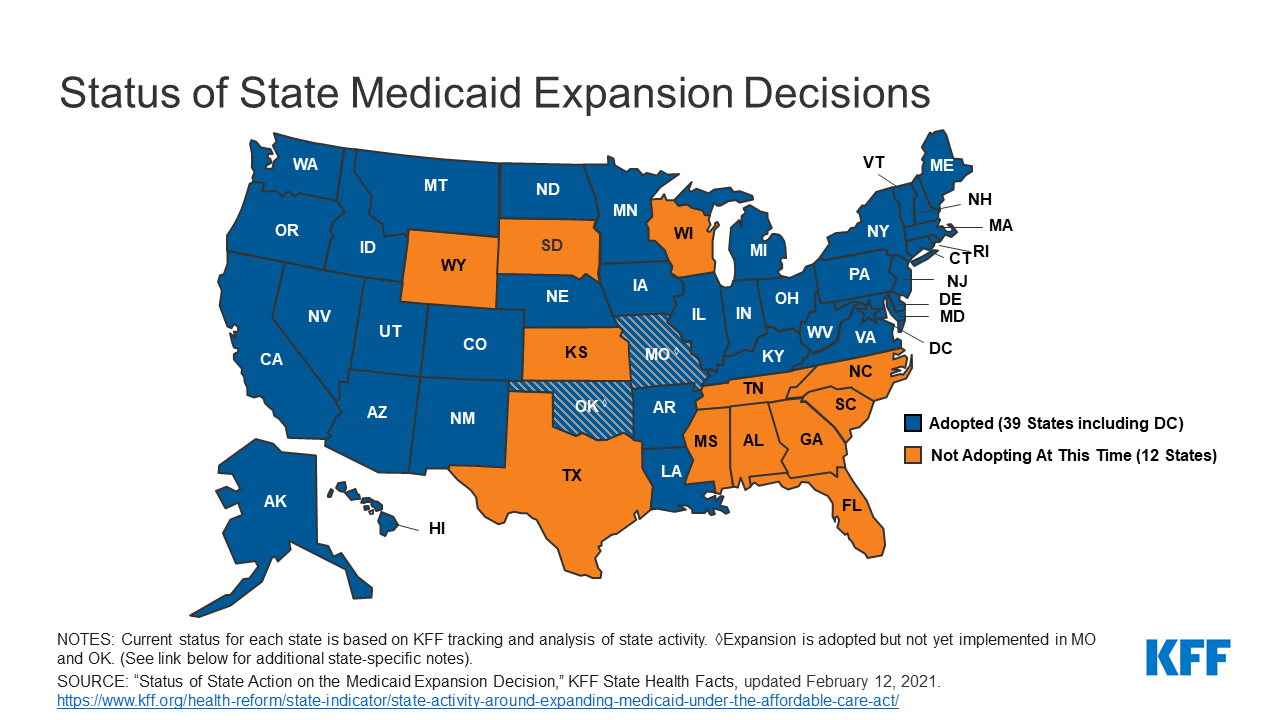

The opportunity emerges as the covid-19 pandemic saps state budgets and strains safety nets. That may help break the Medicaid deadlock in some of the 12 states that have rejected federal funding made available by the Affordable Care Act, health officials, patient advocates and political observers say.

Any breakthrough will require a delicate political balancing act. New Medicaid compromises could leave some states with safety-net programs that, while covering more people, don’t insure as many as Democrats would like. Any expansion deals would also need to allow Republican state officials to tell their constituents they didn’t simply accept the 2010 health law, often called Obamacare.

“Getting all the remaining states to embrace the Medicaid expansion is not going to happen overnight,” said Matt Salo, executive director of the nonpartisan National Association of Medicaid Directors. “But there are significant opportunities for the Biden administration to meet many of them halfway.”

Key to these potential compromises will likely be federal signoff on conservative versions of Medicaid expansion, such as limits on who qualifies for the program or more federal funding, which congressional Democrats have proposed in the latest covid relief bill.

But any deals would bring the country closer to fulfilling the promise of the 2010 law, a pillar of Biden’s agenda, and begin to reverse Trump administration efforts to weaken public programs, which swelled the ranks of the uninsured.

“A new administration with a focus on coverage can make a difference in how these states proceed,” said Cindy Mann, who oversaw Medicaid in the Obama administration and now consults extensively with states at the law firm Manatt, Phelps & Phillips.

Medicaid, the half-century-old health insurance program for the poor and people with disabilities, and the related Children’s Health Insurance Program cover more than 70 million Americans, including nearly half the nation’s children.

Enrollment surged following enactment of the health law, which provides hundreds of billions of dollars to states to expand eligibility to low-income, working-age adults.

However, enlarging the government safety net has long been anathema to most Republicans, many of whom fear that federal programs will inevitably impose higher costs on states.

And although the GOP’s decade-long campaign to “repeal and replace” the health law has largely collapsed, hostility toward it remains high among Republican voters.

That makes it perilous for politicians to embrace any part of it, said Republican pollster Bill McInturff, a partner at Public Opinion Strategies. “A lot of Republican state legislators are sitting in core red districts, looking over their shoulders at a primary challenge,” he said.

Many conservatives have called instead for federal Medicaid block grants that cap how much federal money goes to states in exchange for giving states more leeway to decide whom they cover and what benefits their programs offer.

Many Democrats and patient advocates fear block grants will restrict access to care. But just before leaving office, the Trump administration gave Tennessee permission to experiment with such an approach.

“It’s a frustrating place to be,” said Tom Banning, the longtime head of the Texas Academy of Family Physicians, which has labored to persuade the state’s Republican leaders to drop their opposition to expanding Medicaid. “Despite covid and despite all the attention on health and disparities, we see almost no movement on this issue.”

Some 1.5 million low-income Texans are shut out of Medicaid because the state has resisted expansion, according to estimates by KFF. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.)

An additional 800,000 people are locked out in Florida, which has also blocked expansion.

Two million more are caught in the 10 remaining holdouts: Alabama, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Wisconsin and Wyoming.

Advocates of Medicaid expansion, which is broadly popular with voters, believe they may be able to break through in a handful of these states that allow ballot initiatives, including Mississippi and South Dakota.

Since 2018, voters in Idaho, Nebraska, Utah, Oklahoma and Missouri have backed initiatives to expand Medicaid eligibility, effectively circumventing Republican political leaders.

“The work that we’ve done around the country shows that no matter where people live — red state or blue state — there is overwhelming support for expanding access to health care,” said Kelly Hall, policy director of the Fairness Project, a nonprofit advocacy group that has helped organize the Medicaid measures.

But most of the holdout states, including Texas, don’t allow citizens to put initiatives on the ballot without legislative approval.

And although Florida has an initiative process, mounting a ballot campaign there is challenging, as political advertising is expensive. Unlike in many states, Florida’s leading hospital association hasn’t backed expansion.

Another route for expansion: compromises that could win over skeptical Republican state leaders and still get the green light from the Biden administration.

The Obama administration approved conservative Medicaid expansion in Arkansas, which funneled enrollees into the commercial insurance market, and in Indiana, which forced enrollees to pay more for their medical care.

Money is a major focus of current talks in several states, according to health officials, advocates and others involved in efforts across the country.

The health law at first fully funded Medicaid expansion with federal money, but after the first three years, states had to begin paying part of the tab. Now, states must come up with 10% of the cost of expansion.

Even that small share is a challenge for states, many of which are reeling from the economic downturn caused by the pandemic, said David Becker, a health economist at the University of Alabama-Birmingham who has assisted efforts to expand Medicaid in that state.

“The question is: Where do we get the money?” Becker said, noting that some Republicans may be open to expanding Medicaid if the federal government pays the full cost of the expansion, at least for a year or two.

Other efforts to find ways to offset state costs are underway in Kansas and North Carolina, which have Democratic governors whose expansion plans have been blocked by Republican state legislators. Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly this month proposed using money from the sale and taxation of medical marijuana.

Some Democrats in Congress are pushing to revise the health law to provide full federal funding to states that expand Medicaid now. Separately, in the stimulus bill unveiled last week, House Democrats proposed an additional boost in total Medicaid aid to states that expand.

Other Republicans have signaled interest in partly expanding Medicaid, opening the program to people making up to 100% of the federal poverty level, or about $12,900, rather than 138%, or $17,800, as the law stipulated.

The Obama administration rejected this approach, but the idea has gained traction in several states, including Georgia.

It’s unclear what kind of compromises the new administration may consider, as Biden has yet to even nominate someone to oversee the Medicaid program.

Some Democrats say it’s time to give up the search for middle ground with Republicans on Medicaid.

A better strategy, they say, is a new government insurance plan, or public option, for people in non-expansion states, a strategy Biden endorsed on the campaign trail.

“Democrats can no longer countenance millions of Americans living in poverty without insurance,” said Chris Jennings, a Democratic health care strategist who worked in the White House under Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama and served on Biden’s transition team.

“This is why the Biden public option or other new ways to secure affordable, meaningful care should become the order of the day for people living in states like Florida and Texas.”

Young adults were among the most likely to be uninsured prior to the Affordable Care Act, but the law’s Medicaid expansion had a significant impact on those rates, according to a new study.

Research published by Urban Institute, this week shows the uninsured rate for people aged 19 to 25 declined from 30% to 16% between 2011 and 2018, while Medicaid enrollment for this population increased from 11% to 15% in that window.

The coverage increases were felt most keenly between 2013 and 2016, when many of the ACA’s key tenets were carried out, including Medicaid expansion and the launch of the exchanges, according to the study.

“Before the ACA, adolescents in low-income households often aged out of eligibility for public health insurance coverage through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program as they entered adulthood,” the researchers wrote. “Further, young adults’ employment patterns made them less likely than older adults to have an offer of employer-sponsored insurance coverage.”

States that expanded Medicaid saw greater declines in the number of young people without insurance, the study found.

On average, the uninsured rates among young people declined from nearly 28% in 2011 to 11% in 2018, according to the analysis. In non-expansion states, however, the uninsured rate decreased from about 33% to nearly 21%.

In expansion states, Medicaid enrollment for people aged 19 to 25 rose from 12% in 2011 to close to 21%, according to the study, while enrollment in non-expansion states remained flat.

Urban’s researchers estimate that Medicaid expansion is linked to a 3.6 percent point decline in uninsurance among young people overall, and had the highest impact on young Hispanic people. Uninsurance decreased by 6 percentage points among Hispanic young people, the study found, and that population had the largest uninsured rate prior to the ACA.

“The effects of Medicaid expansion on young adults’ health insurance coverage and health care access provide evidence of the initial pathways through which Medicaid expansions could improve young adults’ overall health and trajectories of health throughout adulthood,” the researchers wrote.

“Beyond coverage and access to preventive care, Medicaid expansion may affect young adults’ health care use in ways not examined in our report. Thus, ensuring young adults have health insurance coverage and access to affordable care is a critical first step toward long-term health,” they wrote.

With nearly 30% of workers now having a high deductible health plan

and a typical family being responsible for on average the first $8,000 of

costs, consumers are increasingly weighing care versus cost.

Historically, with a small copay, you would conveniently take care of an

ailment without shopping around, but with the average person now bearing the brunt of the initial

costs, wouldn’t you want to know how much a service costs and what other providers are

charging before you “buy” the service?

CMS believes “consumers should be able to know, long before they open a medical bill, roughly

how much a hospital will charge for items and services it provides.” Cue the hospital price

transparency rule that just went into effect January 1, 2021. Hospitals are now required to post

their standard charges, including the rates they negotiate with insurers, and the discounted price a

hospital is willing to accept directly from a patient if paid in cash. As a consumer, the intent is to

make it “easier to shop and compare prices across hospitals and estimate the cost of care before

going to the hospital.”

There are a few different angles to analyze here:

Are hospitals following the rules?

Each hospital must post online a comprehensive machine readable file with all items and services, including gross charges, actual negotiated prices with insurers, and the cash price for patients who are uninsured. Additionally, hospitals must post the

costs for 300 common “shoppable” services in a “consumer-friendly format.” Some hospitals and

health systems have done a good job at posting these prices in a digestible format, like the

Cleveland Clinic or Sutter Health, but others have posted complicated spreadsheets, relied on

online cost estimator tools, or simply not posted them at all. An analysis from consulting firm

ADVI of the top 20 largest hospitals in the U.S. found that not all of them appeared to completely

comply with this mandate. In some instances, data was not able to be downloaded in a useable

format, others did not post the DRG or service codes, and the variability in the terms/categories

used simply created difficulty in comparing pricing information across hospitals. CMS has stated

that a failure to comply with the rules could result in a fine of up to $300 per day. As with most

new rules, there are growing pains, and hospitals will likely get better at this over time, assuming

the data is being used for its original intent.

Is this helpful to consumers?

Consumers will able to see the variation in prices for the exact

same service or procedure between hospitals and get an estimate of what they will be charged

before getting the care. But how likely is the average person to go to their hospital’s website, look

at a price, and change their decision about where to get care? In addition, awareness of these

price transparency tools is still low among consumers. Frankly, it is competitors and insurers that

have been first in line to review the data. Looking through a number of hospital websites, and even certain state agency sites that have done a good job at summarizing the costs, like Florida Health Price Finder, the price transparency tools are helpful, but appear to be much more suited for relatively standardized services that can be scheduled in advance, like a knee replacement. It’s highly unlikely you will be telling your ambulance driver what hospital to go to based on cost while in cardiac arrest…Plus, it’s all still confusing – even physicians have shared their bewilderment, when trying to decipher and compare pricing. Conceptually, price transparency should be beneficial to consumers, but it will take time; and it will need to involve not just the hospitals posting rates, but the outpatient care facilities as well. Knowing what you will pay before you decide to go to a physician’s office or a clinic or an urgent care or an ED will hopefully help drive consumers to make more educated decisions in the future.

Will this ultimately drive down costs?

I sure hope so. Revealing actual negotiated prices between hospitals and insurers should

push the more expensive hospitals in the area to reduce prices, especially if consumers start using the other hospitals, instead.

However, it could also have an inverse effect, with lower cost hospitals insisting on a payment increase from insurers; thereby driving up costs. In the end, as has historically been the case, the market power of certain providers will likely dictate the direction of costs in a given region. That is, until both price AND quality become fully transparent and the consumer is armed with the tools to shop for the best care at the lowest cost – consumerism here we come.

https://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/aetna-reenter-affordable-care-act-market

The ACA business has improved and Aetna will sell individual coverage in 2022, CEO says.

After a three-year hiatus, Aetna is reentering the Affordable Care Act market.

Karen Lynch, the new president and CEO of CVS Health, said during an earnings call on Tuesday that Aetna will reenter the ACA business. The ACA business has improved, she said, and Aetna will rejoin the ACA marketplace, selling individual coverage in 2022.

“We’ll accelerate the pace of progress via targeted investments that will drive consumer-focused strategy,” Lynch said. “We will create future economic benefit for CVS Health and its shareholders.”

WHY THIS MATTERS

Aetna said in 2017 that it would leave the market in 2018.

Aetna joined other insurers in leaving or downsizing its footprint as premiums rose and insurers lost money.

The ACA market has grown since the exodus and shown strength in 2021, in lower premiums for consumers, steady enrollment numbers and insurers expanding their marketplace reach.

As COVID-19 has cost many their employer-based health insurance, the Biden Administration has opened a new enrollment period that started on February 15 and goes through May 15.

THE LARGER TREND

President Donald Trump and Congressional GOP members attempted to get rid of the Affordable Care Act that was passed into law by his predecessor, President Barack Obama.

Trump’s successor, President Biden, has promised to strengthen the market, even as the Supreme Court considers whether the ACA law remains valid without the individual mandate’s tax penalty. The Supreme Court is expected to hand down a decision by June.

In 2018, Aetna became part of CVS Health in a $69 billion merger.