https://www.trendsmap.com/twitter/tweet/1251984156998975492

Nobody denies that Chinese officials’ initial effort to cover up the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan at the turn of the year was an appallingly misguided decision. But anyone who is still focusing on China’s failings instead of working toward a solution is essentially making the same mistake.

STOCKHOLM – Does Sweden’s decision to spurn a national lockdown offer a distinct way to fight COVID-19 while maintaining an open society? The country’s unorthodox response to the coronavirus is popular at home and has won praise in some quarters abroad. But it also has contributed to one of the world’s highest COVID-19 death rates, exceeding that of the United States.

In Stockholm, bars and restaurants are filled with people enjoying the spring sun after a long, dark winter. Schools and gyms are open. Swedish officials have offered public-health advice but have imposed few sanctions. No official guidelines recommend that people wear masks.

During the pandemic’s early stages, the government and most commentators proudly embraced this “Swedish model,” claiming that it was built on Swedes’ uniquely high levels of “trust” in institutions and in one another. Prime Minister Stefan Löfven made a point of appealing to Swedes’ self-discipline, expecting them to act responsibly without requiring orders from authorities.

According to the World Values Survey, Swedes do tend to display a unique combination of trust in public institutions and extreme individualism. As sociologist Lars Trägårdh has put it, every Swede carries his own policeman on his shoulder.

But let’s not turn causality on its head. The government did not consciously design a Swedish model for confronting the pandemic based on trust in the population’s ingrained sense of civic responsibility. Rather, actions were shaped by bureaucrats and then defended after the fact as a testament to Swedish virtue.

In practice, the core task of managing the outbreak fell to a single man: state epidemiologist Anders Tegnell at the National Institute of Public Health. Tegnell approached the crisis with his own set of strong convictions about the virus, believing that it would not spread from China, and later, that it would be enough to trace individual cases coming from abroad. Hence, the thousands of Swedish families returning from late-February skiing in the Italian Alps were strongly advised to return to work and school if not visibly sick, even if family members were infected. Tegnell argued that there were no signs of community transmission in Sweden, and therefore no need for more general mitigation measures. Despite Italy’s experience, Swedish ski resorts remained open for vacationing and partying Stockholmers.

Between the lines, Tegnell indicated that eschewing draconian policies to stop the spread of the virus would enable Sweden gradually to achieve herd immunity. This strategy, he stressed, would be more sustainable for society.

Through it all, Sweden’s government remained passive. That partly reflects a unique feature of the country’s political system: a strong separation of powers between central government ministries and independent agencies. And, in “the fog of war,” it was also convenient for Löfven to let Tegnell’s agency take charge. Its seeming confidence in what it was doing enabled the government to offload responsibility during weeks of uncertainty. Moreover, Löfven likely wanted to demonstrate his trust in “science and facts,” by not – like US President Donald Trump – challenging his experts.

It should be noted, though, that the state epidemiologist’s policy choice has been strongly criticized by independent experts in Sweden. Some 22 of the country’s most prominent professors in infectious diseases and epidemiology published a commentary in Dagens Nyheter calling on Tegnell to resign and appealing to the government to take a different course of action.

By mid-March, and with wide community spread, Löfven was forced to take a more active role. Since then, the government has been playing catch-up. From March 29, it prohibited public gatherings of more than 50 people, down from 500, and added sanctions for noncompliance. Then, from April 1, it barred visits to nursing homes, after it had become clear that the virus had hit around half of Stockholm’s facilities for the elderly.

Sweden’s approach turned out to be misguided for at least three reasons. However virtuous Swedes may be, there will always be free riders in any society, and when it comes to a highly contagious disease, it doesn’t take many to cause major harm. Moreover, Swedish authorities only gradually became aware of the possibility of asymptomatic transmission, and that infected individuals are most contagious before they start showing symptoms. And, third, the composition of the Swedish population has changed.

After years of extremely high immigration from Africa and the Middle East, 25% of Sweden’s population – 2.6 million of a total population of 10.2 million – is of recent non-Swedish descent. The share is even higher in the Stockholm region. Immigrants from Somalia, Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan are highly overrepresented among COVID-19 deaths. This has been attributed partly to a lack of information in immigrants’ languages. But a more important factor seems to be the housing density in some immigrant-heavy suburbs, enhanced by closer physical proximity between generations.

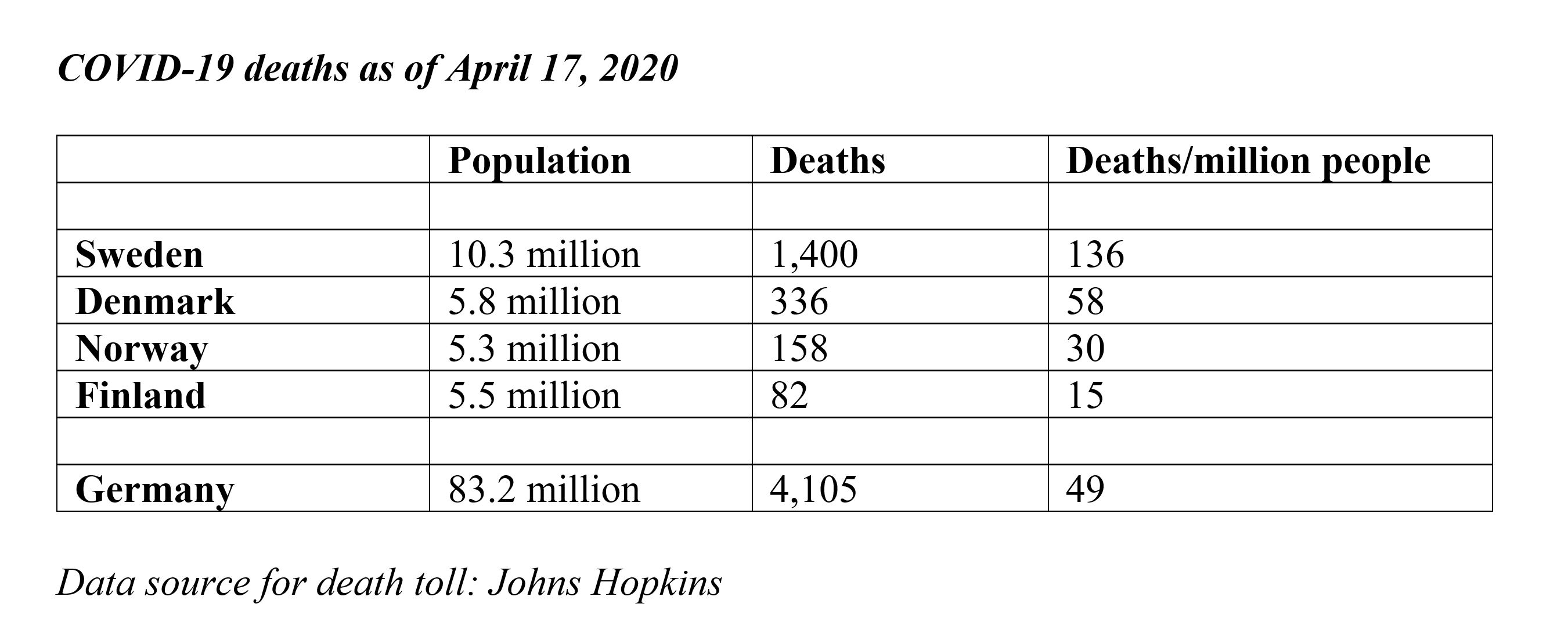

It is too soon for a full reckoning of the effects of the “Swedish model.” The COVID-19 death rate is nine times higher than in Finland, nearly five times higher than in Norway, and more than twice as high as in Denmark. To some degree, the numbers might reflect Sweden’s much larger immigrant population, but the stark disparities with its Nordic neighbors are nonetheless striking. Denmark, Norway, and Finland all imposed rigid lockdown policies early on, with strong, active political leadership.

Now that COVID-19 is running rampant through nursing homes and other communities, the Swedish government has had to backpedal. Others who may be tempted by the “Swedish model” should understand that a defining feature of it is a higher death toll.

As sweeping stay-at-home orders in 42 U.S. states to combat the new coronavirus have shuttered businesses, disrupted lives and decimated the economy, some protesters have begun taking to the streets to urge governors to rethink the restrictions.

A few dozen protesters, many with young children, gathered in Virginia’s state capital of Richmond on Thursday in defiance of Democratic Governor Ralph Northam’s mandate, the latest in a series of demonstrations this week around the country.

The protests have taken on a partisan tone, often featuring supporters of President Donald Trump, and critiquing governors whose shelter-at-home directives are intended to slow the spread of a pandemic that has killed more than 31,000 across the United States.

On Wednesday, thousands of Michigan residents blocked traffic in Lansing, the state capital, while protesters in Kentucky disrupted Democratic Governor Andy Beshear’s afternoon news briefing on the pandemic, chanting “We want to work!”

States including Utah, North Carolina and Ohio also saw demonstrations this week, and more are planned for the coming days, including in Oregon, Idaho and Texas.

The United States has seen the highest death toll of any country in the pandemic, and public health officials have warned that a premature easing of social distancing orders could exacerbate it.

Trump has repeatedly said he wants to “reopen” the economy as soon as possible and has clashed with governors over whether he can overrule their stay-at-home orders.

In Michigan, where Democratic Governor Gretchen Whitmer has imposed some of the country’s toughest limits on travel and business, some protesters at “Operation Gridlock” wore campaign hats and waved signs supporting Trump.

Whitmer is considered a top contender to be the running mate of Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden when he takes on Trump in November’s general election.

One of the organizers of the demonstration in Lansing, Meshawn Maddock, said she was frustrated that much of the media focused on a handful of protesters who gathered on the steps of the capitol, including militia group members and a man holding a Confederate flag who she said were not part of the rally.

She faulted Whitmer for dismissing the event as a partisan rally instead of engaging with the thousands of residents who Maddock said have legitimate questions about the governor’s stay-at-home order.

“When I’m fighting to (help) a guy who cleans pools or mows lawns, or a women who wants to sell her onion sets or geraniums, I don’t care whether they vote Republican, Democrat, or never vote at all,” Maddock said.

Maddock, 52, is among seven board members of the Republican-aligned Michigan Conservative Coalition who organized the protest. She is also a board member of the pro-Trump political action committee Women for Trump, but said the Trump campaign had no involvement in organizing the protest.

“The Trump campaign has given me no messaging,” she said. “All I know is that I care about Michigan. I’ve lived here my whole life and I want to help workers get back to work.”

She said she had received calls from people in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Virginia and other states asking for advice on planning similar protests.

The political wrangling over the COVID-19 crisis has begun to take on familiar partisan battle lines. Democratic strongholds in dense urban centers such as Seattle and Detroit have been hard hit by the virus, while more Republican-leaning rural communities are struggling with the shuttered economy but have seen fewer cases.

Kenny Clevenger, 30, a realtor in western Michigan’s Allegan County, where only 25 coronavirus cases have been identified, said the shutdown had put him out of business.

“Yes, this needs to be taken seriously, but it’s being taken advantage of,” Clevenger said. “People believe Democrats are attempting to use this to undermine the economy, once again just attacking the president.”

Increasingly, Republican state lawmakers, including some in Texas, Oklahoma and Wisconsin, have begun putting pressure on governors to reopen businesses. Pennsylvania’s Republican-led legislature passed a bill that would loosen restrictions, which Democratic Governor Tom Wolf was expected to veto.

Both Democratic and Republican governors have resisted calls to abandon distancing too quickly. On Thursday, five Democratic governors and two Republican governors in the Midwest, including Whitmer in Michigan, said they would coordinate efforts.

Stephen LaSpina, one of the organizers of a “Stand Up to End the Shutdown” protest set for April 20 at Pennsylvania’s capitol in Harrisburg said that its sole goal was to get the economy running again by May 1.

“We are really welcoming groups of all different backgrounds and demographics,” said LaSpina, who lives near Scranton, and like many others who work in retail, said he had personally been affected by the shutdown. “Anyone who has been impacted by this shutdown in a negative way is welcome and we want them to be heard regardless of their party affiliation.”

https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2020/3/31/21199874/coronavirus-spanish-flu-social-distancing

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66580807/2660331.jpg.0.jpg)

A study of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic finds that cities with stricter social distancing reaped economic benefits.

For much of the past month, some commentators have defended the effort to promote social distancing, including the near-shutdown of huge swaths of America’s economy, as the lesser of two evils: Yes, asking or forcing people to remain in their homes for as much of the day as possible will slow economic activity, the argument goes. But it’s worth it for the public health benefits of slowing the coronavirus’s spread.

This argument has, naturally, led to a backlash, explained here by my colleague Ezra Klein. Critics — including the president — have argued that the cure is worse than the disease, and mass death from coronavirus is a price we need to be willing to pay to keep the American economy from cratering.

Both these viewpoints obscure an important possibility: The social distancing regime may well be optimal not just from a public health point of view, but from an economic perspective as well.

Economists Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck, and Emil Verner released a working paper (not yet peer-reviewed) last week that makes this argument extremely persuasively. The three analyzed the 1918-1919 flu pandemic in the United States, as the closest (though still not identical) analogue to the current crisis. They compare cities in 1918-’19 that adopted quarantining and social isolation policies earlier to ones that adopted them later.

Their conclusion? “We find that cities that intervened earlier and more aggressively do not perform worse and, if anything, grow faster after the pandemic is over.”

The researchers refer to such social distancing policies as NPIs, or “non-pharmaceutical interventions,” essentially public health interventions not achieved through medication, like quarantines and school and business closures. The key to the paper is their observation that, in theory, NPIs can both decrease economic activity directly, by keeping people in certain jobs from going to work, and increase it indirectly, because it prevents large-scale deaths that would also have a negative impact on the economy.

“While NPIs lower economic activity, they can solve coordination problems associated with fighting disease transmission and mitigate the pandemic-related economic disruption,” they write. In other words, social distancing measures that save lives can also, in the end, soften the economic disruption of a pandemic.

The data here comes from a 2007 paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association, where a group of researchers chronicled what specific policies were put in place between September 8, 1918, and February 22, 1919, by 43 different cities. The most common NPI the JAMA researchers identified was a combination of school closures and bans on public gatherings; 34 of the 43 cities adopted this rule, for an average of four weeks.

Other cities eschewed these policies in favor of mandatory isolation and quarantine procedures: “Typically, individuals diagnosed with influenza were isolated in hospitals or makeshift facilities, while those suspected to have contact with an ill person (but who were not yet ill themselves) were quarantined in their homes with an official placard declaring that location to be under quarantine,” the JAMA authors write, detailing New York City’s approach.

Another 15 cities did both isolation/quarantines and school closures/public gathering bans.

The 2007 paper found a strong association between the number and duration of NPIs and pandemic deaths, with more and longer-lasting NPIs associated with a smaller death toll. Correia, Luck, and Verner, in their new paper, replicate this finding.

But they take it a step further. They study the impact of changes in mortality due to the 1918 pandemic on economic outcomes.

“The increase in mortality from the 1918 pandemic relative to 1917 mortality levels (416 per 100,000) implies a 23 percent fall in manufacturing employment, 1.5 percentage point reduction in manufacturing employment to population, and an 18 percent fall in output,” they conclude. In other words, a big outbreak spelled economic disaster for affected cities.

Then they combined this analysis with an analysis of the effects of NPI policies. They find that the introduction of social distancing policies is associated with more positive outcomes in terms of manufacturing employment and output. Cities with faster introductions of these policies (one standard deviation faster, to be technical) had 4 percent higher employment after the pandemic had passed; ones with longer durations had 6 percent higher employment after the disaster.

The takeaway is clear: These policies not only led to better health outcomes, they in turn led to better economic outcomes. Pandemics are very bad for the economy, and stopping them is good for the economy.

It’s important to always approach this kind of study with a degree of skepticism. The 1918 pandemic was not a planned experiment, so researchers’ ability to determine the degree to which the pandemic, or the policies adopted in response to it, affected economic outcomes is always going to be somewhat limited.

The researchers acknowledge that their biggest limitation is the non-randomness of policy adoption by cities. Presumably cities with strict responses to the pandemic were different from cities with laxer responses in ways that went beyond this one incident. Maybe the stricter cities had better public health infrastructure to begin with, for instance, which could exaggerate the estimated effect of social distancing interventions.

The authors argue that because the second and most fatal wave of the 1918 pandemic spread mostly from east to west, geographically, these kinds of dynamics weren’t at play. “Given the timing of the influenza wave, cities that were affected later appeared to have implemented NPIs sooner as they were able to learn from cities that were affected in the early stages of the pandemic,” they note.

The best explanation of differences in policies, then, is how far a city is from the East Coast of the US. They control for a big factor that might affect Western states more (the boom and bust of the agricultural industry as World War I drew to a close) and find few other observable differences between Western cities with strong policies and Eastern policies with weak ones. But the notion that these cities are comparable is a key part of the paper’s research design, and one worth digging into as the paper goes through peer review and revisions.

The message that there isn’t a trade-off between saving lives and saving the economy is reassuring. If there were such a trade-off, the debate over coronavirus response would be in the realm of pure values: How much money should we be willing to forsake to save a human life? That’s a thorny choice, and finding that we don’t actually have to make it — as this paper suggests — is comforting.

It’s worth emphasizing, though, that if we did have to make that choice, it would still be an easy decision. The lives saved would be worth more.

In another recent white paper, UChicago’s Michael Greenstone and Vishan Nigam estimate the social value of social distancing policies, relative to a baseline where we endure an untrammeled pandemic. To simulate the two scenarios, they rely on the influential Imperial College London model of the coronavirus pandemic — a paper that found that an uncontrolled spread of coronavirus would kill 2.2 million Americans.

Then they throw in an oft-used tool of cost-benefit economic analysis: the value of a statistical life (VSL). Popularized by Vanderbilt economist Kip Viscusi, VSL involves putting a dollar value on a human life by estimating the implicit value that people in a given society place on continuing to live based on their willingness to pay for services that reduce their risk of dying.

Usually, this involves a “revealed preferences” approach. A 2018 paper by Viscusi, for example, used, among other data sources, Bureau of Labor Statistics Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries to measure how much more, in practice, US workers demand to be paid to take jobs that carry a higher risk of death.

Greenstone and Nigam allow VSL to vary with age — understandably, older people are less willing to pay to reduce their odds of death than younger people — but set the average VSL for an American age 18 and over to $11.5 million.

Based on the Imperial College projection that social distancing would save about 1.76 million lives over the next six months, Greenstone and Nigam estimate that the economic value of the policy is $7.9 trillion, larger than the entire US federal budget and greater than a third of GDP. The value is about $60,000 per US household. Even if the Imperial College model is off by 60 percent and the no-social-distancing scenario is less deadly than anticipated, the aggregate benefits are still $3.6 trillion. And this is likely an underestimate that ignores other costs of a large-scale outbreak to society; it focuses solely on mortality benefits.

VSL is sometimes attacked from the left as craven, a reductio ad absurdum of economistic reasoning trampling over everything, including the value of human life itself. But coronavirus helps illustrate how VSL can work in the opposite direction. Human life is so valuable in these terms that social distancing would have to force a 33 percent drop in US GDP before you could start to plausibly argue that the cure is worse than the disease.

That social distancing likely won’t cause a reduction in GDP relative to a scenario where there’s a multimillion-person death toll, as indicated by the 1918 flu paper, makes the case for distancing policies that much stronger.

PHILADELPHIA DETECTED ITS first case of a deadly, fast-spreading strain of influenza on September 17, 1918. The next day, in an attempt to halt the virus’ spread, city officials launched a campaign against coughing, spitting, and sneezing in public. Yet 10 days later—despite the prospect of an epidemic at its doorstep—the city hosted a parade that 200,000 people attended.

Flu cases continued to mount until finally, on October 3, schools, churches, theaters, and public gathering spaces were shut down. Just two weeks after the first reported case, there were at least 20,000 more.

The 1918 flu, also known as the Spanish Flu, lasted until 1920 and is considered the deadliest pandemic in modern history. Today, as the world grinds to a halt in response to the coronavirus, scientists and historians are studying the 1918 outbreak for clues to the most effective way to stop a global pandemic. The efforts implemented then to stem the flu’s spread in cities across America—and the outcomes—may offer lessons for battling today’s crisis. (Get the latest facts and information about COVID-19.)

From its first known U.S. case, at a Kansas military base in March 1918, the flu spread across the country. Shortly after health measures were put in place in Philadelphia, a case popped up in St. Louis. Two days later, the city shut down most public gatherings and quarantined victims in their homes. The cases slowed. By the end of the pandemic, between 50 and 100 million people were dead worldwide, including more than 500,000 Americans—but the death rate in St. Louis was less than half of the rate in Philadelphia. The deaths due to the virus were estimated to be about 358 people per 100,000 in St Louis, compared to 748 per 100,000 in Philadelphia during the first six months—the deadliest period—of the pandemic.

Dramatic demographic shifts in the past century have made containing a pandemic increasingly hard. The rise of globalization, urbanization, and larger, more densely populated cities can facilitate a virus’ spread across a continent in a few hours—while the tools available to respond have remained nearly the same. Now as then, public health interventions are the first line of defense against an epidemic in the absence of a vaccine. These measures include closing schools, shops, and restaurants; placing restrictions on transportation; mandating social distancing, and banning public gatherings. (This is how small groups can save lives during a pandemic.)

Of course, getting citizens to comply with such orders is another story: In 1918, a San Francisco health officer shot three people when one refused to wear a mandatory face mask. In Arizona, police handed out $10 fines for those caught without the protective gear. But eventually, the most drastic and sweeping measures paid off. After implementing a multitude of strict closures and controls on public gatherings, St. Louis, San Francisco, Milwaukee, and Kansas City responded fastest and most effectively: Interventions there were credited with cutting transmission rates by 30 to 50 percent. New York City, which reacted earliest to the crisis with mandatory quarantines and staggered business hours, experienced the lowest death rate on the Eastern seaboard.

In 2007, a study in the Journal of the American Medial Association analyzed health data from the U.S. census that experienced the 1918 pandemic, and charted the death rates of 43 U.S. cities. That same year, two studies published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences sought to understand how responses influenced the disease’s spread in different cities. By comparing fatality rates, timing, and public health interventions, they found death rates were around 50 percent lower in cities that implemented preventative measures early on, versus those that did so late or not at all. The most effective efforts had simultaneously closed schools, churches, and theaters, and banned public gatherings. This would allow time for vaccine development (though a flu vaccine was not used until the 1940s) and lessened the strain on health care systems.

The studies reached another important conclusion: That relaxing intervention measures too early could cause an otherwise stabilized city to relapse. St. Louis, for example, was so emboldened by its low death rate that the city lifted restrictions on public gatherings less than two months after the outbreak began. A rash of new cases soon followed. Of the cities that kept interventions in place, none experienced a second wave of high death rates. (See photos that capture a world paused by coronavirus.)

In 1918, the studies found, the key to flattening the curve was social distancing. And that likely remains true a century later, in the current battle against coronavirus. “[T]here is an invaluable treasure trove of useful historical data that has only just begun to be used to inform our actions,” Columbia University epidemiologist Stephen S. Morse wrote in an analysis of the data. “The lessons of 1918, if well heeded, might help us to avoid repeating the same history today.”

With mandatory social distancing guidelines and stay-at-home orders in effect throughout the region, and given the grueling demands of their jobs as the deadly coronavirus continues to spread, it would have been nearly impossible to assemble 1,000 health-care workers outside Congress this week.

Instead, volunteers put up 1,000 signs to stand on the lawn in their absence.

Activists who are used to relying on people power to amplify messages and picket lawmakers have been forced to use alternative protest tactics amid the pandemic.

Half a dozen volunteers with liberal activist group MoveOn pressed lawn signs into the grass outside the Capitol as the sun peaked over the Statue of Freedom.

On each sign was a message.

Some, bearing the blue Star of Life seen on the uniforms of doctors, first responders and emergency medical technicians, reiterated a hashtag that has made the rounds on social media for weeks, accompanying posts from desperate front-line workers who say they are running out of necessary protective equipment: #GetUsPPE.

Others showed photos of medical workers in scrubs and hair nets and baseball caps. Some wore face shields and plastic visors. Others donned gloves.

One barefaced doctor in a white lab coat held up a hand-drawn sign. “Trump,” it said. “Where’s my mask?”

Health-care providers in hospitals, clinics, nursing homes, assisted-living facilities and rehabilitation centers have for weeks begged for more PPE to protect themselves and their vulnerable patients.

States and hospitals have been running out of supplies and struggling to find more. The national stockpile is nearly out of N95 respirator masks, face shields, gowns and other critical equipment, the Department of Health and Human Services announced last week.

“Health-care workers are on the front lines of this crisis, and they’re risking their lives to save ours every day, and our government, from the very top of this administration on down, has not used the full force of what they have with the Defense Production Act to ensure [workers] have the PPE they need and deserve,” said Rahna Epting, the executive director of MoveOn. “We wanted to show that these are real people who are demanding that this government protect them.”

Unlike protests that have erupted from Michigan to Ohio to Virginia demanding that states flout social distancing practices and reopen the economy immediately, organizers with MoveOn said they wanted to adhere to health guidelines that instruct people not to gather in large groups.

“Normally, we’d want everyone down here,” said MoveOn volunteer Robby Diesu, 32, as he looked out over the rows of signs. “We wanted to find a way to show the breadth of this problem without putting anyone in harm’s way.”

A large white sign propped at the back of the display announced in bold letters: “Social distancing in effect. Please do not congregate.”

The volunteers who put up the signs live in the same house and have been quarantining under the same roof for weeks. Still, as they worked, several wore masks over their face to protect passersby — even though there were few.

A handful of joggers stopped to take pictures as the sun rose.

One man, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he is a government employee, said he supported the idea.

“I’m so used to seeing protests out here by the Capitol that it really is bizarre to see how empty it is,” he said. “But this is really impressive to me.”

By sharing images and video on social media of front-line workers telling their stories, MoveOn organizers said they hope to galvanize people in the same way as a traditional rally with a lineup of speakers.

Activists planned to deliver a petition to Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) with more than 2 million signatures urging Congress to require the delivery of more PPE to front-line workers. Murphy has been a vocal critic of the Trump administration’s coronavirus task force and its reliance on private companies to deliver an adequate amount of critical gear, such as N95 respirator masks, medical gowns, gloves and face shields, to health-care workers.

“In this critical hour, FEMA should make organized, data-informed decisions about where, when, and in what quantities supplies should be delivered to states — not defer to the private sector to allow them to profit off this pandemic,” the senator wrote last week in a letter to Vice President Pence, co-signed by 44 Democratic and two independent senators.

Organizers said the signs would remain on the Capitol lawn all day, but that the demonstration was only the beginning of a spate of atypical ones the group expects to launch this month.

Epting described activists’ energy as “more intense” than usual as the pandemic drags on.

“The energy is very high, the intensity is very high,” she said. “That’s forcing us to be creative and ingenuitive in order to figure out how to protest in a social distancing posture and keep one another safe at the same time.”

https://mailchi.mp/39947afa50d2/the-weekly-gist-april-17-2020?e=d1e747d2d8

Early reports of hastened recoveries among patients taking the antiviral drug remdesivir sent manufacturer Gilead Sciences’ stock soaring over 8 percent this morning, and contributing to an overall uptick in the market. The gains came after a scoop by healthcare news site STAT, which obtained a copy of an internal webinar from University of Chicago Medicine, where an infectious disease specialist discussed positive results from their early experience with remdesivir. The system recruited 125 patients into Gilead’s Phase 3 clinical trials for the drug; 113 patients had severe disease. The presenting physician reported rapid reductions in fever and improvements in respiratory symptoms, noting that just two patients had died, and most of the participating patients had already been discharged—on average after just six days, suggesting a long course of drug treatment may not be necessary.

The STAT leak comes on the heels of a NEJM article late last week, which reported clinical improvement of over two-thirds in COVID-19 patients who received remdesivir. Critics were quick to point out numerous flaws in the study, including lack of a control group, cherry-picking of patients, and the deep involvement of the manufacturer in study design, many of which also apply to the University of Chicago report.

In the thick of the pandemic, doctors and patients’ families are understandably motivated to get very sick patients access to any treatment that may help—but the resulting frenzy following the publication of early results may make it even harder to get good data to understand what works, and what doesn’t.

In the words of one expert, “Fast trials are generally not very interpretable, interpretable trials are generally not fast”. In the search for a “COVID-19 cure”, it’s highly unlikely that any single drug will provide a cure for the viral illness, and the only way we’ll know if a treatment is truly working is to wait for the results of randomized, controlled trials—despite how frustrating it is to muster the patience to do so.

LONDON – As the COVID-19 crisis roars on, so have debates about China’s role in it. Based on what is known, it is clear that some Chinese officials made a major error in late December and early January, when they tried to prevent disclosures of the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, even silencing health-care workers who tried to sound the alarm. China’s leaders will have to live with these mistakes, even if they succeed in resolving the crisis and adopting adequate measures to prevent a future outbreak.

What is less clear is why other countries think it is in their interest to keep referring to China’s initial errors, rather than working toward solutions. For many governments, naming and shaming China appears to be a ploy to divert attention from their own lack of preparedness. Equally concerning is the growing criticism of the World Health Organization, not least by US President Donald Trump, who has attacked the organization for supposedly failing to hold the Chinese government to account. At a time when the top global priority should be to organize a comprehensive coordinated response to the dual health and economic crises unleashed by the coronavirus, this blame game is not just unhelpful but dangerous.

Globally and at the country level, we desperately need to do everything possible to accelerate the development of a safe and effective vaccine, while in the meantime stepping up collective efforts to deploy the diagnostic and therapeutic tools necessary to keep the health crisis under control. Given that there is no other global health organization with the capacity to confront the pandemic, the WHO will remain at the center of the response, whether certain political leaders like it or not.

Having dealt with the WHO to a modest degree during my time as chairman of the UK’s independent Review on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), I can say that it is similar to most large, bureaucratic international organizations. Like the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the United Nations, it is not especially dynamic or inclined to think outside the box. But rather than sniping at these organizations from the sidelines, we should be working to improve them. In the current crisis, we should be doing everything we can to help both the WHO and the IMF to play an effective, leading role in the global response.

As I have argued before, the IMF should expand the scope of its annual Article IV assessments to include national public-health systems, given that these are critical determinants in a country’s ability to prevent or at least manage a crisis like the one we are now experiencing. I have even raised this idea with IMF officials themselves, only to be told that such reporting falls outside their remit because they lack the relevant expertise.

That answer was not good enough then, and it definitely isn’t good enough now. If the IMF lacks the expertise to assess public-health systems, it should acquire it. As the COVID-19 crisis makes abundantly clear, there is no useful distinction to be made between health and finance. The two policy domains are deeply interconnected, and should be treated as such.

In thinking about an international response to today’s health and economic emergency, the obvious analogy is to the 2008 global financial crisis. Everyone knows that crisis started with an unsustainable US housing bubble, which had been fed by foreign savings, owing to the lack of domestic savings in the United States. When the bubble finally burst, many other countries sustained more harm than the US did, just as the COVID-19 pandemic has hit some countries much harder than it hit China.

And yet, not many countries around the world sought to single out the US for presiding over a massively destructive housing bubble, even though the scars from that previous crisis are still visible. On the contrary, many welcomed the US economy’s return to sustained growth in recent years, because a strong US economy benefits the rest of the world.2

So, rather than applying a double standard and fixating on China’s undoubtedly large errors, we would do better to consider what China can teach us. Specifically, we should be focused on better understanding the technologies and diagnostic techniques that China used to keep its (apparent) death toll so low compared to other countries, and to restart parts of its economy within weeks of the height of the outbreak.

And, for our own sakes, we also should be considering what policies China could adopt to put itself back on a path toward 6% annual growth, because the Chinese economy inevitably will play a significant role in the global recovery. If China’s post-pandemic growth model makes good on its leaders’ efforts in recent years to boost domestic consumption and imports from the rest of the world, we will all be better off.