Other senior executives also cashed out as the company faced a $1.6 billion threat that wreaked havoc throughout the health care system.

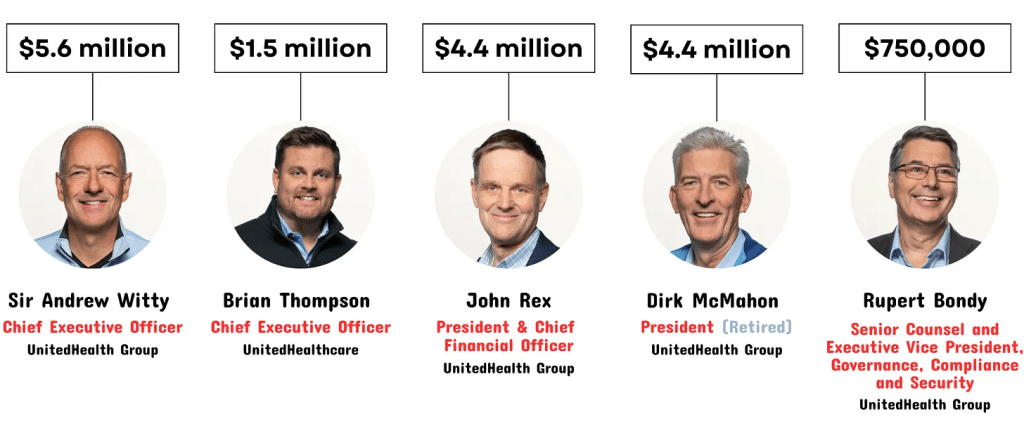

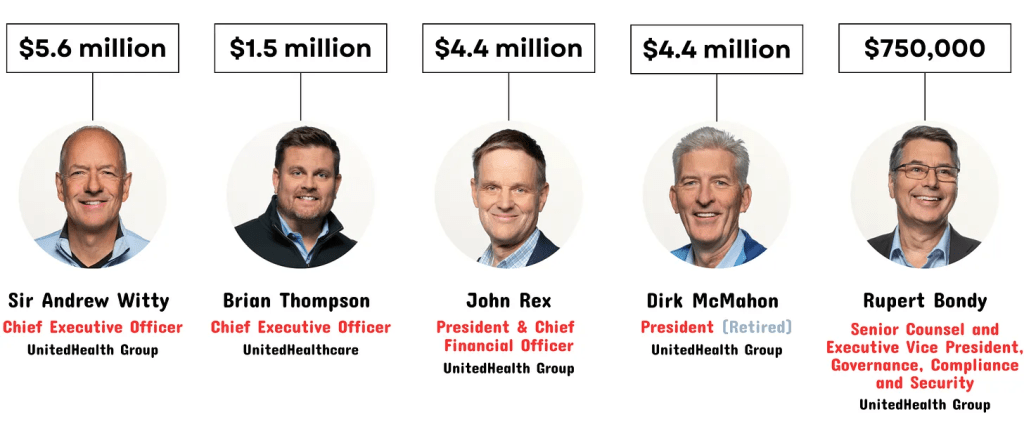

On February 21, the same day that a ransomware attack began to wreak havoc throughout UnitedHealth Group and the U.S. health care system, five of UnitedHealth’s C-suite executives, including CEO Andrew Witty and the company’s chief legal officer, sold $17.7 million worth of their stock in the company. Witty alone accounted for $5.6 million of those sales.

The company’s stock has not recovered since the ransomware attack and has underperformed the S&P 500 index of major stocks by 8% during that time. In the two weeks following the ransomware attack, the company’s stock slid by 10.4%, wiping out more than $46 billion in market cap and greatly reducing the value of shares held by non-insiders. The slide continued for several weeks. On the day Witty and the other executives sold their shares, the stock price closed at $521.97. By April 12, it had fallen to $439.20.

The ransomware attack is estimated to have cost the insurance giant as much as $1.6 billion in total. Witty would later confirm, during his appearance before the Senate Finance Committee on May 1, that the company paid $22 million in ransom to the hackers.

“He (Witty) sold the shares on the same day that he learned of the ransomware attack,” said Richard Painter, a professor at the University of Minnesota School of Law who is also the vice chair of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington. “That’s not good. For the SEC to prove a civil case of insider trading they just have to prove that it’s more probable than not that executives acted on inside information. CEOs have got to be a heck of a lot more careful.

You’re the CEO of a company, you should not be buying or selling the stock right in the middle of a material event like a ransomware attack. You’re asking for trouble. You’re going to end up with an SEC investigation. If that goes badly you could end up with a DOJ investigation.”

How much UnitedHealth’s C-suite executives sold in company stock on February 21, 2024:

Brian Thompson, the CEO of UHG’s insurance arm, sold $1.5 million on the same day. John Rex, then the CFO and now the CFO and president, sold $4.4 million, as did Dirk McMahon, now the former president. Chief Legal Officer Rupert Bondy, who would likely have to have signed off on the sales, sold $750,000.

HEALTH CARE un-covered is the first media outlet to report these disclosures.

The ransomware attack was caused at least in part by negligence on UnitedHealth’s part, Witty admitted at the Finance Committee hearing. He acknowledged that the company had failed to use multi-factor authentication — requiring more than just a password to access information — to secure its data. The cyberattack exposed the personal health information of as much as a third of Americans’ health information.

“This incident and the harm that it caused was, like so many other security breaches, completely preventable and the direct result of corporate negligence,”

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) wrote to federal regulators on May 30. “UHG has publicly confirmed that the hackers gained their initial foothold by logging into a remote access server that was not protected with multi-factor authentication (MFA). MFA is an industry-standard cyber defense that protects against hackers who have guessed or stolen a valid username and password for a system.”

UnitedHealth exploited the crisis created by its own negligence to further entrench its position as the largest employer of doctors in the country, acquiring medical practices that were unable to pay their bills due at least in part to the chaos created by the ransomware attack. The American Medical Association is considering legal action against the company for the attack, with a proposal for its House of Delegates conference beginning June 8 stating that “Optum is the largest employer of physicians and has acquired practices when the ransomware disruption made those practices unable to survive without acquisition… Even the practices that survive will have ongoing damages including but not limited to denials related to giving therapy when it was impossible to obtain prior authorization, from using lines of credit and having to pay interest, from having billing departments and others work overtime to submit claims, to losing key employees from inability to make payroll.”

Other well-timed insider stock transactions

In April, Bloomberg reported that in the lead up to the disclosure of an FTC investigation into UnitedHealth’s monopolistic practices, other UnitedHealth insiders, including Chairman Stephen Hemsley, had sold $102 million worth of their shares.

News of that investigation and the stock sales led Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and other lawmakers to call for an SEC investigation into the trading.

The disclosures revealed here, however, are potentially more incriminating: the executives sold the stock the same day the company became aware of the devastating ransomware attack. When Witty was supposed to be all hands on deck strategizing how to protect health care providers and millions of patients, he spent at least part of his day taking action to preserve his net worth.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

This is not the first time UnitedHealth executives have engaged in questionable or illegal stock transactions. In 2007, former CEO William McGuire agreed to a record $468 million settlement with the SEC after it was learned that for more than a decade he had engaged in a scheme to inflate the value of his holdings in the company and, consequently, his net worth.

An SEC investigation that year found that over a 12-year period, “McGuire repeatedly caused the company to grant undisclosed, in-the-money stock options to himself and other UnitedHealth officers and employees without recording in the company’s books and disclosing to shareholders material amounts of compensation expenses as required by applicable accounting rules.” In other words, he was back-dating his stock options.

As the SEC explained:

[F]rom at least 1994 through 2005, McGuire looked back over a window of time and picked grant dates for UnitedHealth options that coincided with dates of historically low quarterly closing prices for the company’s common stock, resulting in grants of in-the-money options.

According to the complaint, McGuire signed and approved backdated documents falsely indicating that the options had actually been granted on these earlier dates when UnitedHealth’s stock price was at or near these low points.

These inaccurate documents caused the company to understate compensation expenses for stock options, and were routinely provided to the company’s external auditors in connection with their audits and reviews of UnitedHealth’s financial statements.