Category Archives: Leadership Values

Cartoon – Getting Back to First Principles

Cartoon – We believe in

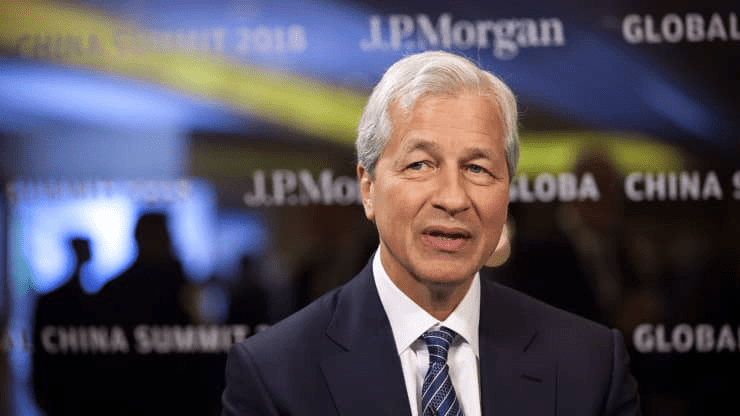

People with these traits succeed–‘not the smartest or hardest-working in the room’

According to Jamie Dimon, chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, the most successful leaders have certain key traits.

″[H]umility, openness, fairness [and] being authentic” are most important – “not [being] the smartest person in the room or the hardest working person in the room,” Dimon, who runs the nation’s largest bank and oversees more than 250,000 employees globally, told LinkedIn editor in chief Daniel Roth in a recent video.

“Management is: Get it done, follow-up, discipline, planning, analysis, facts, facts, facts. It’s [getting] the right people in the room, kill the bureaucracy, all of these various things,” Dimon told Roth. “But the real keys to leadership aren’t just doing that.”

It’s about having “respect for people,” not about having “charisma” or “brain power,” he said.

Having these traits also increases your productivity, along with your success, Dimon said. If you’re “selfish” or “take the credit” when it isn’t warranted, others are “not going to want to work,” which will impact efficiency on the job.

Dimon also looks for these things when hiring, he said in July. When interviewing or assessing a promotion, Dimon asks himself a few questions about the candidate, including, “Would you work for that person? Would you want your kid to work for that person?”

He also considers whether they “take the blame” or “how they act anytime something goes wrong.”

In his role as CEO, Dimon said he tries to practice what he preaches.

“No one would say Jamie Dimon is humble,” he said in July, “but I treat everyone the same, and I expect the same thing. You’d want to work for me if you think I give a s—, if I treat you fairly, if I treat everyone equally.”

To achieve success, “treat people the way you want to be treated,” Dimon told Roth. “Have respect for people.”

Is Healthcare Headed for Best of Times or Worst of Times?

Citi, The American Hospital Association (AHA) and the Healthcare Financial Management Association (HFMA) recently hosted the 22nd annual Not-for-Profit Healthcare Investor Conference. The event was in person, after being virtual in 2021 and canceled in 2020 due to the pandemic. Leaders from over 25 diverse health systems, as well as private equity and fund managers, presented in panel discussions and traditional formats. The following summary attempts to synthesize key themes and particularly interesting work by leading health systems. The conference title was “Refining the Now, Reshaping What’s Next.”

Is Healthcare Headed for Best of Times or Worst of Times?

Clearly the pandemic showed how essential and adaptive the US healthcare industry is, and especially how incredible healthcare workers continue to be. It also exposed and accelerated many underlying dynamics, such as impact of disparities, clinical labor shortages and supply chain challenges. On balance, at this year’s conference presenters remained quite optimistic about the future, and felt that despite enormous pain, the pandemic has helped to accelerate positive transformation across healthcare.

At the same time, almost all presenters referenced future headwinds from labor and supply inflation, concerns about increasing payment pressures, and the continued need to address disparities and social justice. That being said, there was not much disclosure at the conference about just how bad things could get in the future given accelerated operational and financial risks.

As usual at such a conference, there was much passion, creativity, sharing and celebration. While each organization and market differ somewhat, the following are common themes discussed.

Key Themes

Enormous Workforce Challenges – Every speaker referenced workforce as being THE key issue they are facing, specifically retirement, recruitment, retention, well-being and cost. We have talked for years about a future caregiver shortage, but this reality was accelerated by the pandemic. The majority of health systems saw single-digit turnover rates grow to 20-30%, and the cost of temporary labor such as traveling nurses, decimate operating margins. The many strategies discussed at the conference went beyond simply paying more to attract and retain staff. A key question is whether organization-specific strategies will be enough, or whether we need a broader societal and industry-wide collaborative effort to dramatically increase training slots for nurses and other allied health professionals.

Pandemic Stressed Organizations and Accelerated Transformation – At the 2021 virtual Citi/AHA/HFMA conference, many posited that the country was past the worst of the pandemic. (In fact this author’s summary of last year’s conference was titled “Sunrise After the Storm”). That was before the Omicron wave hit hard in Q1 2022. First-quarter 2022 operating margins were negative for most but not all healthcare systems due to cumulative impact of Omicron, temporary labor and supply costs, especially since the governmental support that partially offset those costs in 2020 ended. Organizations and their teams remain resilient, but highly stressed. Risks and challenges associated with future waves continue, as well as high reliance on foreign drug and supply manufacturing. While highly distracting and painful, many organizations discussed how the pandemic actually accelerated the pace of transformation. Necessity drives required action, and at least temporarily overcomes political and cultural barriers to change.

Growing Pursuit of Scale, Including through M&A and Partnerships – All health systems continue to be highly complex with multiple competing “big-dot” priorities. Multiple systems described their current M&A and growth strategies, pursuit of scale, as well as how these strategies were impacted by the pandemic. While the provider community remains highly unconsolidated on a national basis, mergers are more frequent, including between non-contiguous markets. Systems said that larger size, coupled with disciplined management, can reduce cost structure and improve quality and patient experience. While some pursue scale through organic growth initiatives or M&A, others described success in creating scale by leveraging partnerships with “best-in-class” niche organizations and other outside expertise.

Health Equity, Diversity and ESG as Core to Mission – Consistent with last year, most speakers discussed their efforts to address health equity, social justice, diversity, and Social Determinants of Health. Many health systems have developed robust strategies quickly as the pandemic spotlighted the impact of existing disparities. There is increasing interest in Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) initiatives, including environmental stewardship to improve the health of their communities and the world by reducing their carbon footprint and medical waste.

Patient-Centric Care Transformation Continues as a Priority – The pandemic significantly accelerated the shift to telehealth and virtual care. Many health systems are increasing their efforts to design care around the patient instead of the traditional provider centric focus. While the need for inpatient care will always continue, more care is taking place in settings closer to or at home, with digital enablement. Expansion of personalized medicine, genetic testing and therapies, and drug discovery are transforming how healthcare is provided.

Affordability and Value-Based Care – US healthcare costs as a percentage of GDP increased from 18% in 2019 to almost 20% in 2020, mainly driven by the pandemic. There remains a dichotomy between reliance on fee-for-service payment and commitment to value-based care. Although only 11% of commercial payment is currently through two-sided risk arrangements, almost all presenting health systems discussed their strategies to continue moving to value-based care and to improve affordability. Some systems are leveraging their integrated health plans and/or expanding risk-based contracts. Many are trying to reduce unnecessary care through adoption of evidence-based models and to shift care to less costly settings.

Inflation and Accelerating Financial Pressures – Health systems are facing unprecedented increases in labor and supply costs, that are likely to continue into the foreseeable future. At the same time, commercial payment rate adjustments are “sticky low” as insurers and employers push back on rate increases. Governmental payment rate increases are less than cost inflation. In addition to current cuts like the re-implementation of sequestration, longer-term cuts to provider assessment programs, provider-based billing, disproportionate share and Medicaid expansion may severely impact many organizations over time. Benefits like 340b discounts are also experiencing pressure. Post-pandemic clinical-volume trends remain unclear, and additional governmental support associated with future pandemic waves is unlikely. Adding to these challenges, declines in stock and bond prices are negatively impacting currently strong balance sheets.

Conclusion: Best or Worst of Times in Healthcare?

Time will tell, in retrospect, if the next five years will be the best of times, worst of times, or both in healthcare. Optimists point to the resiliency of healthcare organizations; enormous opportunity to reduce unnecessary cost through adoption of evidence-based care and scale; pipeline of new cures and technology; and opportunities to address social and health equity. Pessimists point to likely unprecedented financial pressures and operational challenges due to endemic labor and supply shortages; high-cost inflation vs. constrained payment rates; and future uncertainty about the pandemic, the economy and investment markets.

The situation will undoubtedly vary by market and organization as reflected in conference presentations, but all systems will likely face substantial pressure. As one speaker noted “humans have a great ability to respond to pain,” so this may be the inflection point where more healthcare systems radically accelerate necessary change to improve health, make healthcare more equitable and affordable, with higher quality and better outcomes. Some health systems are clearly doing that, with pace, nimbleness and passion. Can the industry as a whole accomplish it successfully?

Former patient kills his surgeon and three others at a Tulsa hospital

https://mailchi.mp/31b9e4f5100d/the-weekly-gist-june-03-2022?e=d1e747d2d8

On Wednesday afternoon, an aggrieved patient shot and killed four people, including his orthopedic surgeon and another doctor, at a Saint Francis Hospital outpatient clinic, before killing himself. The gunman, who blamed his surgeon for ongoing pain after a recent back surgery, reportedly purchased his AR-15-style rifle only hours before the mass shooting, which also injured 10 others. The same day as this horrific attack, an inmate receiving care at Miami Valley Hospital in Dayton, OH shot and killed a security guard, and then himself.

The Gist: On the heels of the horrendous mass shootings in Buffalo and Uvalde, we find ourselves grappling with yet more senseless gun violence. Last week, we called on health system leaders to play a greater role in calling for gun law reforms. This week’s events show they must also ensure that their providers, team members, and patients are safe.

Of course, that’s a tall order, as hospital campuses are open for public access, and strive to be convenient and welcoming to patients. Most health systems already staff armed security guards or police officers, have a limited number of unlocked entrances, and provide active shooter training for staff.

This week’s events remind us that our healthcare workers are not just on the front lines of dealing with the horrific outcomes of gun violence, but may find themselves in the crosshairs—adding to already rising levels of workplace violence sparked by the pandemic.

Something must change.

Gun violence, the leading cause of death among US children, claims more victims

https://mailchi.mp/d73a73774303/the-weekly-gist-may-27-2022?e=d1e747d2d8

Only 10 days after a racially motivated mass shooting that killed 10 in a Buffalo, NY grocery store, 19 children and two teachers were murdered on Tuesday at an elementary school in Uvalde, TX. The Uvalde shooting was the 27th school shooting, and one of over 212 mass shootings, that have occurred this year alone.

Firearms recently overtook car accidents as the leading cause of childhood deaths in the US, and more than 45,000 Americans die from gun violence each year.

The Gist: Gun violence is, and has long been, a serious public health crisis in this country. It is both important to remember, yet difficult for some to accept, that many mass shootings are preventable.

Health systems, as stewards of health in their communities, can play a central role in preventing gun violence at its source, both by bolstering mental health services and advocating for the needed legislative actions—supported by a strong majority of American voters—to stem this public health crisis.

As Northwell Health CEO Michael Dowling said this week, “Our job is to save lives and prevent people from illness and death. Gun violence is not an issue on the outside—it’s a central public health issue for us. Every single hospital leader in the United States should be standing up and screaming about what an abomination this is. If you were hesitant about getting involved the day before…May 24 should have changed your perspective. It’s time.”

The MacArthur Tenets

https://www.leadershipnow.com/macarthurprinciples.html

Douglas MacArthur was one of the finest military leaders the United States ever produced. John Gardner, in his book On Leadership described him as a brilliant strategist, a farsighted administrator, and flamboyant to his fingertips. MacArthur’s discipline and principled leadership transcended the military. He was an effective general, statesman, administrator and corporate leader.

William Addleman Ganoe recalled in his 1962 book, MacArthur Close-up: An Unauthorized Portrait, his service to MacArthur at West Point. During World War II, he created a list of questions with General Jacob Devers, they called The MacArthur Tenets. They reflect the people-management traits he had observed in MacArthur. Widely applicable, he wrote, “I found all those who had no troubles from their charges, from General Sun Tzu in China long ago to George Eastman of Kodak fame, followed the same pattern almost to the letter.”![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Do I heckle my subordinates or strengthen and encourage them?

Do I heckle my subordinates or strengthen and encourage them?

![]() Do I use moral courage in getting rid of subordinates who have proven themselves beyond doubt to be unfit?

Do I use moral courage in getting rid of subordinates who have proven themselves beyond doubt to be unfit?

![]() Have I done all in my power by encouragement, incentive and spur to salvage the weak and erring?

Have I done all in my power by encouragement, incentive and spur to salvage the weak and erring?

![]() Do I know by NAME and CHARACTER a maximum number of subordinates for whom I am responsible? Do I know them intimately?

Do I know by NAME and CHARACTER a maximum number of subordinates for whom I am responsible? Do I know them intimately?

![]() Am I thoroughly familiar with the technique, necessities, objectives and administration of my job?

Am I thoroughly familiar with the technique, necessities, objectives and administration of my job?

![]() Do I lose my temper at individuals?

Do I lose my temper at individuals?

![]() Do I act in such a way as to make my subordinates WANT to follow me?

Do I act in such a way as to make my subordinates WANT to follow me?

![]() Do I delegate tasks that should be mine?

Do I delegate tasks that should be mine?

![]() Do I arrogate everything to myself and delegate nothing?

Do I arrogate everything to myself and delegate nothing?

![]() Do I develop my subordinates by placing on each one as much responsibility as he can stand?

Do I develop my subordinates by placing on each one as much responsibility as he can stand?

![]() Am I interested in the personal welfare of each of my subordinates, as if he were a member of my family?

Am I interested in the personal welfare of each of my subordinates, as if he were a member of my family?

![]() Have I the calmness of voice and manner to inspire confidence, or am I inclined to irascibility and excitability?

Have I the calmness of voice and manner to inspire confidence, or am I inclined to irascibility and excitability?

![]() Am I a constant example to my subordinates in character, dress, deportment and courtesy?

Am I a constant example to my subordinates in character, dress, deportment and courtesy?

![]() Am I inclined to be nice to my superiors and mean to my subordinates?

Am I inclined to be nice to my superiors and mean to my subordinates?

![]() Is my door open to my subordinates?

Is my door open to my subordinates?

![]() Do I think more of POSITION than JOB?

Do I think more of POSITION than JOB?

![]() Do I correct a subordinate in the presence of others?

Do I correct a subordinate in the presence of others?

Patton’s Principles of Leadership

BORN in San Gabriel, California, in 1885, George S. Patton, Jr. was the general deemed most dangerous by the German High Command in World War II. Known for his bombastic style, it was mostly done to show confidence in himself and his troops, says author Owen Connelly.

On December 21, 1945, Patton died in Heidelberg, Germany. The following day the New York Times wrote the following editorial:

History has reached out and embraced General George Patton. His place is secure. He will be ranked in the forefront of America’s great military leaders.

Long before the war ended, Patton was a legend. Spectacular, swaggering, pistol-packing, deeply religious, and violently profane, easily moved to anger because he was first of all a fighting man, easily moved to tears because, underneath all his mannered irascibility, he had a kind heart, he was a strange combination of fire and ice. Hot in battle and ruthless, too. He was icy in his inflexibility of purpose. He was no mere hell-for-leather tank commander but a profound and thoughtful military student.

![]() Everyone is to lead in person.

Everyone is to lead in person.

![]() Commanders and staff members are to visit the front daily to observe, not to meddle. Praise is more valuable than blame. Your primary mission as a leader is to see with your own eyes and be seen by your troops while engaged in personal reconnaissance.

Commanders and staff members are to visit the front daily to observe, not to meddle. Praise is more valuable than blame. Your primary mission as a leader is to see with your own eyes and be seen by your troops while engaged in personal reconnaissance.

![]() Issuing an order is worth only about 10 percent. The remaining 90 percent consists in assuring proper and vigorous execution of the order.

Issuing an order is worth only about 10 percent. The remaining 90 percent consists in assuring proper and vigorous execution of the order.

![]() Plans should be simple and flexible. They should be made by the people who are going to execute them.

Plans should be simple and flexible. They should be made by the people who are going to execute them.

![]() Information is like eggs. The fresher the better.

Information is like eggs. The fresher the better.

![]() Every means must be used before and after combats to tell the troops what they are going to do and what they have done.

Every means must be used before and after combats to tell the troops what they are going to do and what they have done.

![]() Fatigue makes cowards of us all. Men in condition do not tire.

Fatigue makes cowards of us all. Men in condition do not tire.

![]() Courage. Do not take counsel of your fears.

Courage. Do not take counsel of your fears.

![]() A diffident manner will never inspire confidence. A cold reserve cannot beget enthusiasm. There must be an outward and visible sign of the inward and spiritual grace.

A diffident manner will never inspire confidence. A cold reserve cannot beget enthusiasm. There must be an outward and visible sign of the inward and spiritual grace.

![]() Discipline is based on pride in the profession of arms, on meticulous attention to details, and on mutual respect and confidence. Discipline must be a habit so ingrained that it is stronger than the excitement of battle or the fear of death.

Discipline is based on pride in the profession of arms, on meticulous attention to details, and on mutual respect and confidence. Discipline must be a habit so ingrained that it is stronger than the excitement of battle or the fear of death.

![]() A good solution applied with vigor now is better than a perfect solution ten minutes later.

A good solution applied with vigor now is better than a perfect solution ten minutes later.

Rudeness is on the rise — why?

It’s not just you, and it’s not just in healthcare: Poor behavior ranging from the impolite to the violent is having a moment in society right now.

The Atlantic’s Olga Khazan spoke with more than a dozen experts on crime, psychology and social norms to suss out contributing factors to the spike in poor behavior, which she details in her piece, “Why People Are Acting So Weird,” published March 30.

Stress is one likely explanation for the bad behavior. Keith Humphreys, PhD, a psychiatry professor at Stanford, told Ms. Khazan the pandemic has created a lot of “high-stress, low-reward” situations, in which someone who has experienced a lot of loss due to the pandemic may be pushed over the edge by an inoffensive request.

Not only are people encountering more provocations — like staff shortages or mask mandates — but their mood is worse when provoked.

“Americans don’t really like each other very much right now,” Ryan Martin, PhD, a psychology professor at the University of Wisconsin at Green Bay who studies expressions of anger, told Ms. Khazan.

It doesn’t help that rudeness can be contagious. At work, people can spread negative emotions to colleagues, bosses and clients regardless of whether those people were the source of the negativity.

“People who witness rudeness are three times less likely to help someone else,” Christine Porath, PhD, a business professor at Georgetown University, said in the report.

Just as the pandemic has reaped high-stress, low-reward moments, it has brought on a level of isolation that has affected how people behave.

“We’re more likely to break rules when our bonds to society are weakened,” Robert Sampson, PhD, a Harvard sociologist, told Ms. Khazan. “When we become untethered, we tend to prioritize our own private interests over those of others or the public.”

Richard Rosenfeld, PhD, a criminologist at the University of Missouri at St. Louis, went one step further to describe society operating with “a generalized sense that the rules simply don’t apply.”

Ms. Khazan makes a point to distinguish mental health in the broader conversation about poor behavior.

“People with severe mental illness are only a tiny percentage of the population, and past research shows that they commit only 3 to 5 percent of violent acts, so they couldn’t possibly be responsible for the huge surge in misbehavior,” she said.

For a quantified look at how problematic behavior — including crime, dangerous driving, unruly passenger incidents and student disciplinary problems — has spiked, turn to journalist Matthew Yglesias’ deep dive, born from his observation that “the extent to which we seem to be living through a pretty broad rise in aggressive and antisocial behavior” is underdiscussed.