Category Archives: Mergers & Acquisitions

General Catalyst announces intent to buy a health system

https://mailchi.mp/de5aeb581214/the-weekly-gist-october-13-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

On Sunday, venture capital (VC) firm General Catalyst unveiled the Health Assurance Transformation Corporation (HATCo), a new subsidiary company which aims to acquire a health system to serve as a blueprint for the VC firm’s vision of healthcare transformation.

Sharing this news on the first day of the HLTH 2023 conference in Las Vegas, General Catalyst declined to comment on which health systems are targets, or how much it is willing to spend, but CEO Hemant Taneja suggested that investment returns would be evaluated on a longer timeline than the typical 10-year venture capital horizon.

Dr. Marc Harrison, the former CEO of Intermountain Health who joined General Catalyst in 2022, has been tapped to lead HATCo. The new company will build on General Catalyst’s previously announced partnerships with health systems, including Intermountain, HCA Healthcare, and Universal Health Services, with the goal of connecting healthcare startups with health systems in order to test and scale their technologies.

The Gist: While private equity firms have backed health systems before, a VC firm expressing interest in health system ownership is a surprising development.

Even on a longer timeframe than most venture plays get, it’s difficult to imagine a health system ever delivering the outsized returns VC investors usually demand. It’s possible HATCo’s true value will come from scaling and selling the services of tech startups in General Catalyst’s portfolio after vetting them at their health system “proving ground”.

HATCo’s more ambitious aim to align payers and providers in a pivot to value-based care is a familiar one, but the new venture will find itself up against skepticism from insurers and other entrenched stakeholders, which has been difficult for even the most motivated health systems to overcome.

Walmart reportedly exploring purchase of ChenMed

https://mailchi.mp/e1b9f9c249d0/the-weekly-gist-september-15-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

Bloomberg reported this week that retail behemoth Walmart has engaged in talks to acquire a majority stake in ChenMed, a closely held value-based primary care company based in Miami, FL.

The deal would significantly expand Walmart’s primary care footprint and capabilities, adding to the 39 Walmart Health centers slated to be in operation by the end of this year.

ChenMed, which operates 120+ clinics across 15 states, delivers primary care to complex Medicare Advantage beneficiaries, taking risk for the total cost of care, and has grown its membership by 36 percent annually across the last decade. It has remained privately owned by the Chen family, but recently revamped its leadership structure and tapped UnitedHealth Group (UHG) veteran Steve Nelson to run operations. ChenMed has an expected value of several billion dollars, a price that could be driven upwards if other bidders express interest. Bloomberg’s sources emphasized that the deal could still be weeks away and that no terms have been finalized.

The Gist: Should this purchase go through, it might change Walmart’s status as a “sleeping giant” in healthcare.

ChenMed’s primary care model and strong foothold in the Southeast would dovetail with Walmart’s store clinic footprint and its 10-year partnership with UHG to drive value-based care adoption in that region.

With ChenMed competitors Oak Street, One Medical, and VillageMD now backed or owned by some of Walmart’s biggest competitors, Walmart may view ChenMed as its best opportunity to scale its primary care footprint through a large acquisition.

However, much of ChenMed’s success to date has been attributed to its strong culture and track record of physician recruitment and retention—something a large company like Walmart may have challenges preserving.

Private equity could worsen cardiology’s overutilization problem

https://mailchi.mp/e1b9f9c249d0/the-weekly-gist-september-15-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

An article published this week in Stat documents private equity’s move into the cardiovascular space. There’s reason to suspect private equity ownership could exacerbate cardiology’s overuse problem, according to several cardiologists and researchers. Studies has found private equity acquisition results in more patients, more visits per patient, and higher charges.

Outpatient atherectomies have become a poster child for overutilization, with the volume billed to Medicare more than doubling from 2011-2021.

The Gist: Fueled by the growing number of states allowing outpatient cardiac catheterization, all signs point to cardiovascular practices being the next specialty courted for PE rollups.

However, the service line brings more complexities to deal structure and future returns than recent targets like dermatology and orthopedics. Heart and vascular groups are more heterogeneous, and less profitable medical management of conditions like congestive heart failure accounts for a greater portion of patient volume. Much more of the medical group business is intertwined with inpatient care, and, unlike other proceduralists, around 80 percent of cardiologists are already employed by health systems. While that doesn’t mean health systems are safe from cardiologists seceding for the promise of PE windfalls,

the closer PE firms get to the “heart” of medicine, the more they’ll find their standard playbook at odds with the broad spectrum of care that cardiovascular specialists provide—and the more they’ll find that partnering with local hospitals will be non-negotiable to maintain the book of business.

Private equity-backed practices flexing market share muscle

https://mailchi.mp/d0e838f6648b/the-weekly-gist-september-8-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

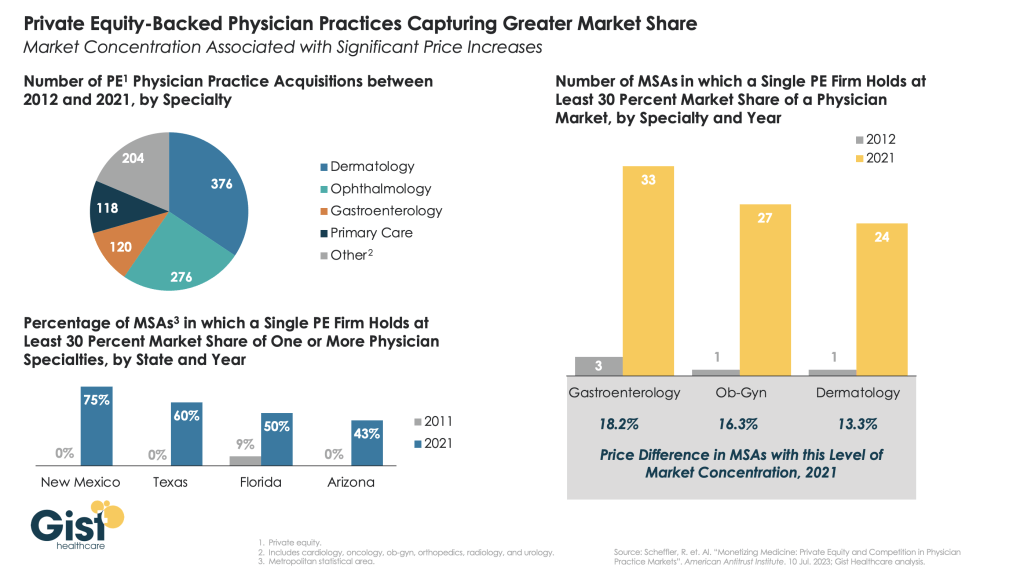

This week we showcase data from a recent American Antitrust Institute study on the growth of private equity (PE)-backed physician practices, and the impact of this growth on market competition and healthcare prices.

From 2012 to 2021, the annual number of practice acquisitions by private equity groups increased six-fold, especially in high-margin specialties. During this same time period, the number of metropolitan areas in which a single PE-backed practice held over 30 percent market share rose to cover over one quarter of the country.

These “hyper-concentrated” markets are especially prevalent in less-regulated states with fast-growing senior populations, like Arizona, Texas, and Florida.

The study also found an association between PE practice acquisitions and higher healthcare prices. In highly concentrated markets, certain specialties, like gastroenterology, were able to raise prices rise by as much as 18 percent.

While new Federal Trade Commission proposals demonstrate the government’s renewed interest in antitrust enforcement, it may be too little, too late to mitigate the impact of specialist concentration in many states.

Some states back hospital mergers despite record of service cuts, price hikes

In much of the country, a single hospital system now accounts for most hospital admissions.

Some illnesses and injuries — say, a broken ankle — can send you to numerous health care providers. You might start at urgent care but end up in the emergency room. Referred to an orthopedist, you might eventually land in an outpatient surgery center.

Four different stops on your road to recovery. But as supersized health care systems gobble up smaller hospitals and clinics, it’s increasingly likely that all those facilities will be owned by the same corporation.

Hospital trade groups say mergers can save failing hospitals, especially rural ones. But research shows that a lack of competition often leads to fewer services at higher costs. In recent years, federal regulators have been taking a harder look at health care consolidation.

Yet some states, notably those in the South, are paving the way for more mergers.

Mississippi passed a law this year that exempts hospital acquisitions from state antitrust laws, while North Carolina considered legislation to do the same for the University of North Carolina’s health system. Louisiana officials approved a $150 million hospital acquisition late last year that has ignited a legal battle with the Federal Trade Commission over whether they allowed a monopoly.

States including South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia have certificate of public advantage (COPA) laws that let state agencies determine whether hospitals can merge, circumventing federal antitrust laws. And large hospital systems wield significant political power in many state capitals.

‘A tool in the tool belt’

Nearly half of Mississippi’s rural hospitals are at risk of closing, according to a report from the Center for Healthcare Quality & Payment Reform, a nonprofit policy research center.

Mississippi leaders hope easing restrictions on hospital mergers could be a solution. A new law exempts all hospital acquisitions and mergers from state antitrust laws and classifies community hospitals as government entities, making them immune from antitrust enforcement.

We saw primary care offices get shut down. We’ve seen our specialists leave for out of state. Several of the outlying hospitals saw services cut even though they were told it wouldn’t happen.

– Kerri Wilson, a registered nurse in North Carolina

Mississippi, one of the poorest states in the nation, is also one of the least healthy, with high rates of chronic conditions like heart disease and diabetes. It is one of 10 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, and has one of the nation’s highest percentages of people without health insurance.

“Like many states in a similar socioeconomic status, Mississippi has difficulties with patients that are either not insured or underinsured,” said Ryan Kelly, executive director of the nonprofit Mississippi Rural Health Association. Food insecurity and lack of reliable transportation mean rural residents tend to be sicker and more expensive to treat.

That’s part of the reason why so many Mississippi hospitals operate in the red. The largest hospital in the Mississippi Delta region, Greenwood Leflore, is at immediate risk of closure even after hospital leaders shuttered unit after unit — including labor and delivery, and intensive care — in an effort to remain solvent.

A deal for the University of Mississippi Medical Center to purchase Greenwood Leflore fell through last year. Now, with the new law in effect, the hospital’s owners — the city and county — are soliciting new bidders and offering them the option to buy the hospital outright.

Kelly said he expects to see more Mississippi hospitals consolidate over the coming decade. Some have already had conversations around merger possibilities after the new law went into effect, though talks are in early days.

“It’s a tool in the tool belt,” he said of the new law. “I think it could be a saving grace for some of our hospitals that are perennially struggling but still serve with good purpose. They could be part of a larger system that could help offset their costs so they’re able to be a little leaner but still provide services in their community.”

Leaders in some states think consolidation could solve their health care woes, but studies indicate it has a negative impact.

“There’s a large body of research showing that health care consolidation leads to increases in prices without clear evidence it improves quality,” said Zachary Levinson, a project director at KFF, a nonprofit health care policy research organization, who analyzes the business practices of hospitals and other providers and their impact on costs.

When researchers studied how affiliation with a larger health system affected the number of services a rural hospital offered, they found most of the losses in service occurred in hospitals that joined larger systems, according to a 2023 study from the Rural Policy Research Institute at the University of Iowa.

Even when an acquisition by a larger health system helps a struggling hospital keep its doors open, “there can be potential tradeoffs,” Levinson said.

“There’s some concern that, for example, when a larger health system buys up a smaller independent hospital in a different region, that hospital will become less attentive to the specific needs of the community it serves,” and may cut services the community wants because they’re not deemed profitable enough, he said.

Most research suggests hospital consolidation does lead to higher prices, according to a sweeping 2020 report from MedPAC, an independent congressional agency that advises Congress on issues affecting Medicare. The report found that patients with private insurance pay higher prices for care and for insurance in markets that are dominated by one health care system. And when hospitals acquire physician practices, taxpayer and patient costs can double for some services provided in a physician’s office, the report found.

Kelly said he’s not as concerned with consolidation raising costs for Mississippi’s rural residents because so many qualify for subsidized care, but he does think mergers could eliminate some jobs in the health care sector.

“It’s hard to say for sure,” he said. “It is a risk, no question. But I still think it’s a net positive.”

A ‘hospital cartel’

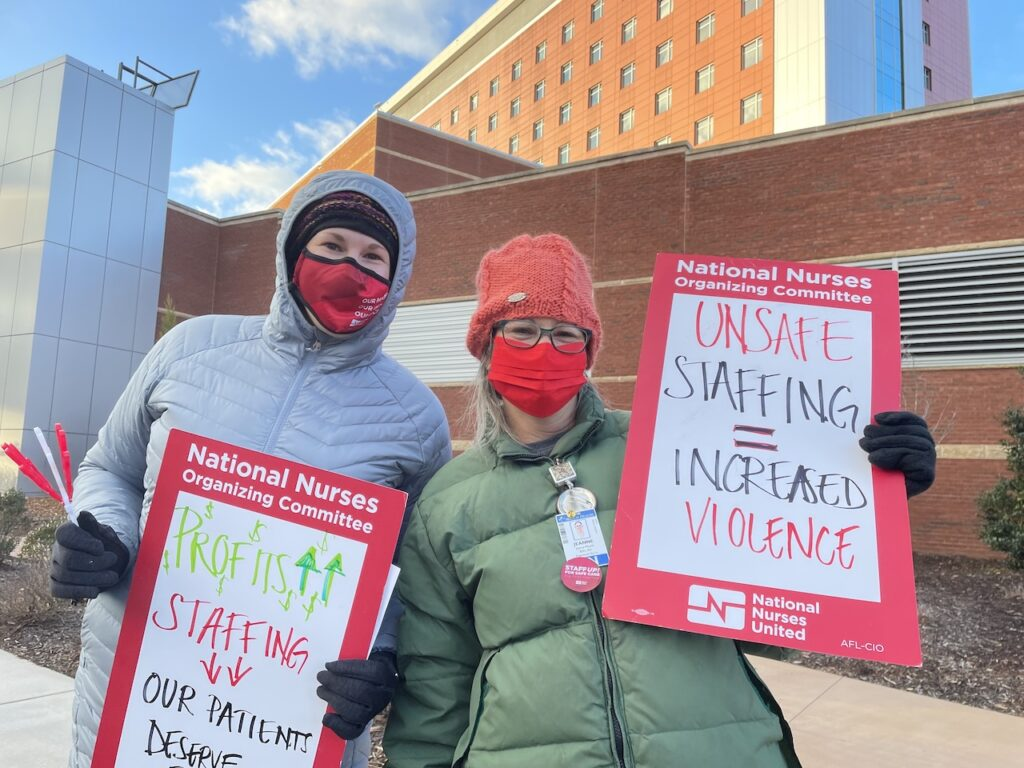

When HCA Healthcare purchased a North Carolina hospital system in 2019, registered nurse Kerri Wilson wasn’t prepared for how much would change — and how quickly — at her hospital in Asheville.

“Once the sale was final in 2019, that’s when it was like the ball dropped and we started seeing staffing cuts,” said Wilson, an Asheville native who has worked in the cardiology stepdown unit at Mission Hospital since 2016.

“We saw our nurse-patient ratios change,” Wilson said. “We saw primary care offices get shut down. We’ve seen our specialists leave for out of state. Several of the outlying hospitals saw services cut even though they were told it wouldn’t happen.”

In the four years since HCA Healthcare bought Mission Health, North Carolinians have hit the nation’s largest health system with multiple antitrust lawsuits, including one that asserts HCA operates an unlawful health care monopoly through Mission Health, and another filed by city and county governments that says HCA’s corporate practices have decimated local health care options and raised costs.

HCA Healthcare did not immediately respond to a request for comment. However, when the second lawsuit was filed, HCA/Mission Health spokesperson Nancy Lindell called it “meritless.”

“Mission Health has been caring for Western North Carolina for more than 130 years and our dedication to providing excellent health care to our community will not waiver [sic] as we vigorously defend against this meritless litigation,” Lindell said in a statement to the Mountain Xpress newspaper. “We are disappointed in this action and we continue to be proud of the heroic work our team does daily.”

Mission’s nurses voted in 2020 to join National Nurses Organizing Committee, an affiliate of National Nurses United, the nation’s largest nursing union, to advocate for higher pay and safer working conditions.

Meanwhile, North Carolina leaders such as Republican State Treasurer Dale Folwell and Democratic Attorney General Josh Stein have spoken out against HCA’s practices. Folwell likened the merger to a “hospital cartel” and both officials filed amicus briefs supporting the plaintiffs in the antitrust lawsuits.

“We have a situation with the cartel-ization of health care in North Carolina where people have to drive miles just to get basic services, and this is unacceptable,” Folwell told Stateline. He said many North Carolinians, particularly those with low incomes, fear seeking medical help because of sky-high medical bills that he said are a result of massive health care systems with little state oversight.

Folwell has publicly criticized the power that the North Carolina Health Care Association, the state’s hospital trade group, wields in the legislature. He calls the group the “leader of the [hospital] cartel.”

Industry groups spent more than $141 million nationwide lobbying state officials on health issues in 2021. And out of that $141 million, the hospital and nursing home industry spent the most, accounting for nearly 1 out of every 4 dollars spent on lobbying state lawmakers over health issues.

“This is not a Republican or Democrat issue,” said Folwell, who has lent his support to a bipartisan bill that would limit the power of large hospitals to charge interest rates and rein in medical debt collection tactics. “It’s a moral issue.”

North Carolina Democratic state Sen. Julie Mayfield, who was on the Asheville City Council when HCA acquired Mission Health, sponsored a bill earlier this year that would have curbed hospital consolidations.

In a social media post introducing the bill, Mayfield said she hoped it would “prevent other communities from suffering what we have suffered in the wake of the Mission sale — loss of nursing and other staff, loss of physicians, closure of facilities, and the resulting lower quality of care many people have experienced in Mission hospitals over the last four years.”

Even the Federal Trade Commission jumped in, urging legislators to “reconsider” a bill that would have greenlighted UNC Health’s expansion, saying it could “lead to patient harm in the form of higher health care costs, lower quality, reduced innovation and reduced access to care.” That bill ultimately failed in the state House, as sentiment among some North Carolina leaders had already soured on hospital mergers.

In most U.S. markets, a single hospital system now accounts for more than half of hospital inpatient admissions. Federal regulators have been scrutinizing health care mergers more carefully in recent years, said KFF’s Levinson. The FTC has both sued and been sued by health care systems in Louisiana this year, and recently released a draft version of new guidelines on anti-competitive practices.

“People have viewed those guidelines as indicating the FTC and [the U.S. Department of Justice] will be more interested in aggressively challenging anti-competitive practices than in the past,” Levinson said.

Both the Trump and Biden administrations issued executive orders directing federal agencies to focus on promoting competition in health care markets. President Joe Biden’s order noted that “hospital consolidation has left many areas, particularly rural communities, with inadequate or more expensive healthcare options.”

In Mississippi, the hospital mergers law received widespread support from most of the state’s GOP leaders. But the state’s far-right Freedom Caucus came out against it, with Republican state Rep. Dana Criswell, the chair of the caucus, calling it “an attempt at a complete government takeover” of Mississippi’s hospitals.

Criswell said allowing the University of Mississippi Medical Center to buy smaller hospitals “will create a huge government protected monopoly, driving out competition and ultimately putting private hospitals out of business.”

‘Trying something different’

Wilson, the Asheville nurse, said she used to have three or four patients per shift before the merger; now she typically has five. That gives her an average of 10 minutes per patient per hour. It’s not enough time, she said, to give patients their medication, answer questions and perform other tasks that she said nurses often take on because other departments are short-staffed.

Sometimes, she said, those tasks include helping patients go to the bathroom because there aren’t enough nursing assistants or taking out the trash because of a shortage of cleaning staff. Meanwhile, the waiting rooms are overflowing.

Wilson joined the new Mission Hospital nurses union, which was able to negotiate raises for its members. The union continues to protest working conditions, including staff-patient ratios.

But Kelly, of the Mississippi Rural Health Association, said that in his state, mergers are an opportunity for positive change.

“It’s not like health care in Mississippi is at the top of the list for good things,” he said. “I think this is an example of trying something different and seeing if it works.”

How to convince the board that it’s time to merge

https://mailchi.mp/27e58978fc54/the-weekly-gist-august-11-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

This week we had a conversation with a health system executive who has been wondering how to make the case to his board for expansion beyond the existing markets where the organization operates.

Like many, he’s confronting declining margin performance, and feeling pressure to combine with another system—joining the wave of cross-market consolidation that’s been dominating discussion among system CEOs recently.

His concern was that his locally governed board may be putting an artificial brake on growth, not seeing value of expansion beyond their market for the community they serve.

That’s a valid point—how does it help a Busytown resident if the local health system expands to operate in Pleasantville? Shouldn’t Busytown Health System just focus its resources and time on improving performance at home, and wouldn’t it represent a loss to Busytown if Pleasantville got investment dollars that could have been spent locally?

That’s a question raised by the “super-regional” or national strategies being pursued by many large systems today, and one worth thinking about.

Whenever a system grows outside its geography, there should be a solid argument that additional scale will reap returns for its existing operations, from better efficiency, better access to innovation and talent, better access to capital, or the like.

Those are legitimate reasons for out-of-market growth and consolidation, as long as the systems involved are diligent in pursuing them.

But local boards are right to hold executives accountable for making the case for growth, and ensuring that growth creates value for local patients and purchasers.

Babylon Health to end US business as proposed go-private deal falls through

https://mailchi.mp/27e58978fc54/the-weekly-gist-august-11-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

The beleaguered digital health company announced on Monday that its previously proposed arrangement to go private via a deal with Swiss-based neurotechnology company MindMaze will not happen, offering no further details. That deal was arranged by AlbaCore Capital Group, which had secured a loan for Babylon in May to implement the transaction.

Babylon said that it will now exit its core US businesses, which consist mostly of value-based agreements with health plans, and will continue to seek a buyer for its Meritage Medical Network, a California-based independent practice association (IPA) comprised of approximately 1,800 physicians.

Babylon said it may have to file for bankruptcy if it can’t secure additional funding or reach another deal to divest.

The Gist: Babylon is one of the starkest digital health “boom-and-bust” stories thus far. Despite the fact that the company overpromised and under-delivered in both the US and abroad, it was able to raise—and then lose—billions of dollars in just a few short years after going public in October 2021 via a special purpose acquisition corporation (SPAC) merger. It remains to be seen who will buy Babylon’s attractive IPA asset. Presumably insurers, retailers, health systems and other players are evaluating a purchase, either to enter or expand their provider footprint into Northern and Central California.

New antitrust merger guidelines could further slow healthcare deals

https://mailchi.mp/c02a553c7cf6/the-weekly-gist-july-28-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

Last week the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) proposed thirteen new merger guidelines that, if finalized, would provide federal regulators greater ability to scrutinize mergers across all industries, including healthcare.

The guidelines expand which mergers could be potentially illegal and therefore worth probing, including those with lower monetary value and those in which the newly combined organization would control 30 percent or greater market share, and would increase scrutiny on transactions that are part of a series of multiple acquisitions by an organization. They also seek to limit the ability of an organization to justify an acquisition on the grounds that the weaker party in the deal would be unable to continue to operate. Comments on the guidelines are being accepted until September 18.

The Gist: To date, federal regulators have struggled to prevent non-traditional mergers between companies that provide different services, operate in different markets, or are below the monetary threshold for review.

The proposed guidelines would significantly increase FTC and DOJ scrutiny at all levels of hospital mergers, and also jeopardize physician and other care asset acquisitions by health systems, payers, and private equity-backed organizations. They are the latest from the Biden Administration in a recent, multi-part push to reduce consolidation through greater antitrust enforcement.

This effort includes last month’s proposal to add additional reporting requirements for mergers outlined in the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act, as well as the FTC’s move earlier this month to withdraw two antitrust policy statements focused on healthcare markets that both agencies say are now “outdated.” Those now-rescinded statements provided guidance on antitrust safety zones, including for accountable care organizations participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program and for mergers between two hospitals in which one is much smaller.

Quantifying private equity’s takeover of physician practices

https://mailchi.mp/cc1fe752f93c/the-weekly-gist-july-14-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

A detailed report, published by a group of organizations including the American Antitrust Institute, provides one of the highest-quality examinations of the growth of private equity (PE)-backed physician practices, and the impact of this growth on market competition and healthcare prices.

From 2012 to 2021, the annual number of practice acquisitions by private equity groups increased six-fold, and the number of metropolitan areas in which a single PE-backed practice held over 30 percent market share rose to cover over one quarter of the country. (Check out figure 3B at the bottom of page 20 in the report to see if you live in one of those markets.)

The study also found an association between PE practice acquisitions and higher healthcare prices and per-patient expenditures. In highly concentrated markets, certain specialties, like gastroenterology, saw prices rise by as much as 18 percent.

The Gist: As the report highlights, one of the greatest barriers to assessing PE’s impact on physician practices is the lack of transparency around acquisitions and ownership structures. This analysis brings us closer to understanding the scope of the issue, and makes a strong case for regulatory and legislative intervention.

Recent proposed changes to federal premerger disclosure requirements offer a good start, but many practice acquisitions are still too small to flag review, and slowing future acquisitions will do little to unwind the market concentration already emerging.

PE is also not the sole actor contributing to healthcare consolidation, and proposed remedies may target the activities of payers and health systems considered anti-competitive as well.