But allies and opponents agree he has failed at the one task that could help him achieve all his goals — confronting the pandemic with a clear strategy and consistent leadership.

Trump’s shortcomings have perplexed even some of his most loyal allies, who increasingly have wondered why the president has not at least pantomimed a sense of command over the crisis or conveyed compassion for the millions of Americans hurt by it.

People close to Trump, many speaking on the condition of anonymity to share candid discussions and impressions, say the president’s inability to wholly address the crisis is due to his almost pathological unwillingness to admit error; a positive feedback loop of overly rosy assessments and data from advisers and Fox News; and a penchant for magical thinking that prevented him from fully engaging with the pandemic.

In recent weeks, with more than 145,000 Americans now dead from the virus, the White House has attempted to overhaul — or at least rejigger — its approach. The administration has revived news briefings led by Trump and presented the president with projections showing how the virus is now decimating Republican states full of his voters. Officials have also set up a separate, smaller coronavirus working group led by Deborah Birx, the White House coronavirus response coordinator, along with Trump son-in-law and senior adviser Jared Kushner.

For many, however, the question is why Trump did not adjust sooner, realizing that the path to nearly all his goals — from an economic recovery to an electoral victory in November — runs directly through a healthy nation in control of the virus.

“The irony is that if he’d just performed with minimal competence and just mouthed words about national unity, he actually could be in a pretty strong position right now, where the economy is reopening, where jobs are coming back,” said Ben Rhodes, a deputy national security adviser to former president Barack Obama. “And he just could not do it.”

Many public health experts agree.

“The best thing that we can do to set our economy up for success and rebounding from the last few months is making sure our outbreak is in a good place,” said Caitlin Rivers, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “People are not going to feel comfortable returning to activities in the community — even if it’s allowed from a policy perspective — if they don’t feel the outbreak is under control.”

Some aides and outside advisers have tried to stress to Trump and others in his orbit that before he could move on to reopening the economy and getting the country back to work — and life — he needed to grapple with the reality of the virus.

But until recently, the president was largely unreceptive to that message, they said, not fully grasping the magnitude of the pandemic — and overly preoccupied with his own sense of grievance, beginning many conversations casting himself as the blameless victim of the crisis.

In the past couple of weeks, senior advisers began presenting Trump with maps and data showing spikes in coronavirus cases among “our people” in Republican states, a senior administration official said. They also shared projections predicting that virus surges could soon hit politically important states in the Midwest — including Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin, the official said.

This new approach seemed to resonate, as he hewed closely to pre-scripted remarks in a trio of coronavirus briefings last week.

“This could have been stopped. It could have been stopped quickly and easily. But for some reason, it wasn’t, and we’ll figure out what that reason was,” Trump said Thursday, seeming to simultaneously acknowledge his predicament while trying to assign blame elsewhere.

In addition to Birx and Kushner, the new coronavirus group guiding Trump includes Kushner advisers Adam Boehler and Brad Smith, according to two administration officials. Marc Short, chief of staff to Vice President Pence, also attends, along with Alyssa Farah, the White House director of strategic communications, and Stephen Miller, Trump’s senior policy adviser.

The working group’s goal is to meet every day, for no more than 30 minutes. It views its mission as half focused on the government’s response to the pandemic and half focused on the White House’s public message, the officials said.

White House spokeswoman Sarah Matthews defended the president’s handling of the crisis, saying he acted “early and decisively.”

“The president has also led an historic, whole-of-America coronavirus response — resulting in 100,000 ventilators procured, sourcing critical PPE for our front-line heroes, and a robust testing regime resulting in more than double the number of tests than any other country in the world,” Matthews said in an email statement. “His message has been consistent and his strong leadership will continue as we safely reopen the economy, expedite vaccine and therapeutics developments, and continue to see an encouraging decline in the U.S. mortality rate.”

For some, however, the additional effort is too little and far too late.

“This is a situation where if Trump did his job and put in the work to combat the health crisis, it would solve the economic crisis, and it’s an instance where the correct governing move is also the correct political move, and Trump is doing the opposite,” said Josh Schwerin, a senior strategist for Priorities USA, a super PAC supporting former vice president Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic nominee.

Other anti-Trump operatives agree, saying he could make up lost ground and make his race with Biden far more competitive with a simple course correction.

“He’s staring in the mirror at night: That’s who can fix his political problem,” said John Weaver, one of the Republican strategists leading the Lincoln Project, a group known for its anti-Trump ads.

One of Trump’s biggest obstacles is his refusal to take responsibility and admit error.

In mid-March, as many of the nation’s businesses were shuttering early in the pandemic, Trump proclaimed in the Rose Garden, “I don’t take responsibility at all.” Those six words have neatly summed up Trump’s approach not only to the pandemic, but also to many of the other crises he has faced during his presidency.

“His operating style is to double- and triple-down on positions and to never, ever admit he’s wrong about anything,” said Anthony Scaramucci, a longtime Trump associate who briefly served as White House communications director and is now a critic of the president. “His 50-year track record is to bulldog through whatever he’s doing, whether it’s Atlantic City, which was a failure, or the Plaza Hotel, which was a failure, or Eastern Airlines, which was a failure. He can never just say, ‘I got it wrong and let’s try over again.’ ”

Another self-imposed hurdle for Trump has been his reliance on a positive feedback loop. Rather than sit for briefings by infectious-disease director Anthony S. Fauci and other medical experts, the president consumes much of his information about the virus from Fox News and other conservative media sources, where his on-air boosters put a positive spin on developments.

Consider one example from last week. About 6:15 a.m. that Tuesday on “Fox & Friends,” co-host Steve Doocy told viewers, “There is a lot of good news out there regarding the development of vaccines and therapeutics.” The president appears to have been watching because, 16 minutes later, he tweeted from his iPhone, “Tremendous progress being made on Vaccines and Therapeutics!!!”

It is not just pro-Trump media figures feeding Trump positive information. White House staffers have long made upbeat assessments and projections in an effort to satisfy the president. This, in turn, makes Trump further distrustful of the presentations of scientists and reports in the mainstream news media, according to his advisers and other people familiar with the president’s approach.

This dynamic was on display during an in-depth interview with “Fox News Sunday” anchor Chris Wallace that aired July 19. After the president claimed the United States had one of the lowest coronavirus mortality rates in the world, Wallace interjected to fact-check him: “It’s not true, sir.”

Agitated by Wallace’s persistence, Trump turned off-camera to call for White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany. “Can you please get me the mortality rates?” he asked. Turning to Wallace, he said, “Kayleigh’s right here. I heard we have one of the lowest, maybe the lowest mortality rate anywhere in the world.”

Trump, relying on cherry-picked White House data, insisted that the United States was “number one low mortality fatality rates.”

Fox then interrupted the taped interview to air a voice-over from Wallace explaining that the White House chart showed Italy and Spain doing worse than the United States but countries like Brazil and South Korea doing better — and other countries that are doing better, including Russia, were not included on the White House chart. By contrast, worldwide data compiled by Johns Hopkins University shows the U.S. mortality rate is far from the lowest.

Trump is also predisposed to magical thinking — an unerring belief, at an almost elemental level, that he can will his goals into existence, through sheer force of personality, according to outside advisers and former White House officials.

The trait is one he shares with his late father and family patriarch, Fred Trump. In her best-selling memoir, “Too Much and Never Enough,” the president’s niece, Mary L. Trump, writes that Fred Trump was instantly taken by the “shallow message of self-sufficiency” he encountered in Norman Vincent Peale’s 1952 bestseller, “The Power of Positive Thinking.”

Some close to the president say that when Trump claims, as he did twice last week, that the virus will simply “disappear,” there is a part of him that actually believes the assessment, making him more reluctant to take the practical steps required to combat the pandemic.

Until recently, Trump also refused to fully engage with the magnitude of the crisis. After appointing Pence head of the coronavirus task force, the president gradually stopped attending task force briefings and was lulled into a false sense of assurance that the group had the virus under control, according to one person familiar with the dynamic.

Trump also maintained such a sense of grievance — about how the virus was personally hurting him, his presidency and his reelection prospects — that aides recount spending valuable time listening to his gripes, rather than focusing on crafting a national strategy to fight the pandemic.

Nonetheless, some White House aides insist the president has always been focused on aggressively responding to the virus. And some advisers are still optimistic that if Trump — who trails Biden in national polls — can sustain at least a modicum of self-discipline and demonstrate real focus on the pandemic, he can still prevail on Election Day.

Others are less certain, including critics who say Trump squandered an obvious solution — good governance and leadership — as the simplest means of achieving his other goals.

“There is quite a high likelihood where people look back and think between February and April was when Trump burned down his own presidency, and he can’t recover from it,” Rhodes said. “The decisions he made then ensured he’d be in his endless cycle of covid spikes and economic disruption because he couldn’t exhibit any medium- or long-term thinking.”

LONDON – As the COVID-19 crisis roars on, so have debates about China’s role in it. Based on what is known, it is clear that some Chinese officials made a major error in late December and early January, when they tried to prevent disclosures of the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, even silencing health-care workers who tried to sound the alarm. China’s leaders will have to live with these mistakes, even if they succeed in resolving the crisis and adopting adequate measures to prevent a future outbreak.

What is less clear is why other countries think it is in their interest to keep referring to China’s initial errors, rather than working toward solutions. For many governments, naming and shaming China appears to be a ploy to divert attention from their own lack of preparedness. Equally concerning is the growing criticism of the World Health Organization, not least by US President Donald Trump, who has attacked the organization for supposedly failing to hold the Chinese government to account. At a time when the top global priority should be to organize a comprehensive coordinated response to the dual health and economic crises unleashed by the coronavirus, this blame game is not just unhelpful but dangerous.

Globally and at the country level, we desperately need to do everything possible to accelerate the development of a safe and effective vaccine, while in the meantime stepping up collective efforts to deploy the diagnostic and therapeutic tools necessary to keep the health crisis under control. Given that there is no other global health organization with the capacity to confront the pandemic, the WHO will remain at the center of the response, whether certain political leaders like it or not.

Having dealt with the WHO to a modest degree during my time as chairman of the UK’s independent Review on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), I can say that it is similar to most large, bureaucratic international organizations. Like the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the United Nations, it is not especially dynamic or inclined to think outside the box. But rather than sniping at these organizations from the sidelines, we should be working to improve them. In the current crisis, we should be doing everything we can to help both the WHO and the IMF to play an effective, leading role in the global response.

As I have argued before, the IMF should expand the scope of its annual Article IV assessments to include national public-health systems, given that these are critical determinants in a country’s ability to prevent or at least manage a crisis like the one we are now experiencing. I have even raised this idea with IMF officials themselves, only to be told that such reporting falls outside their remit because they lack the relevant expertise.

That answer was not good enough then, and it definitely isn’t good enough now. If the IMF lacks the expertise to assess public-health systems, it should acquire it. As the COVID-19 crisis makes abundantly clear, there is no useful distinction to be made between health and finance. The two policy domains are deeply interconnected, and should be treated as such.

In thinking about an international response to today’s health and economic emergency, the obvious analogy is to the 2008 global financial crisis. Everyone knows that crisis started with an unsustainable US housing bubble, which had been fed by foreign savings, owing to the lack of domestic savings in the United States. When the bubble finally burst, many other countries sustained more harm than the US did, just as the COVID-19 pandemic has hit some countries much harder than it hit China.

And yet, not many countries around the world sought to single out the US for presiding over a massively destructive housing bubble, even though the scars from that previous crisis are still visible. On the contrary, many welcomed the US economy’s return to sustained growth in recent years, because a strong US economy benefits the rest of the world.2

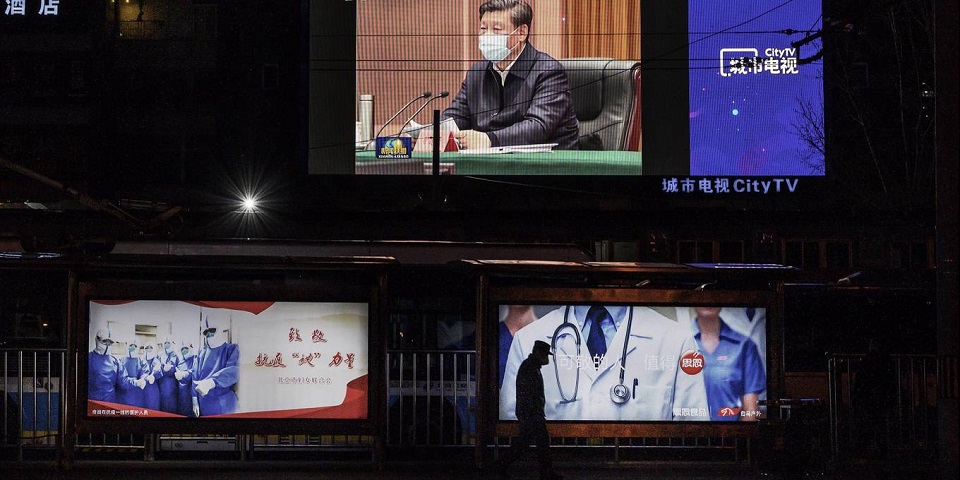

So, rather than applying a double standard and fixating on China’s undoubtedly large errors, we would do better to consider what China can teach us. Specifically, we should be focused on better understanding the technologies and diagnostic techniques that China used to keep its (apparent) death toll so low compared to other countries, and to restart parts of its economy within weeks of the height of the outbreak.

And, for our own sakes, we also should be considering what policies China could adopt to put itself back on a path toward 6% annual growth, because the Chinese economy inevitably will play a significant role in the global recovery. If China’s post-pandemic growth model makes good on its leaders’ efforts in recent years to boost domestic consumption and imports from the rest of the world, we will all be better off.