https://mailchi.mp/ce4d4e40f714/the-weekly-gist-june-10-2022?e=d1e747d2d8

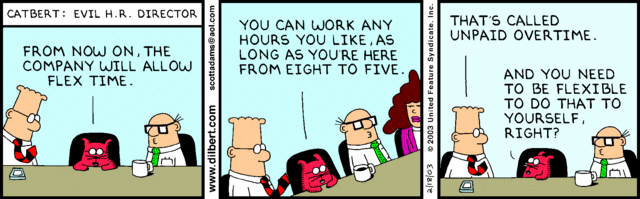

A consultant colleague recently recounted a call from a health system looking for support in physician alignment. He mused, “It’s never a good sign when I hear that the medical group reports to the system CFO [chief financial officer].” We agree. It’s not that CFOs are necessarily bad managers of physician networks, or aren’t collaborative with doctors—as you’d expect from any group of leaders, there are CFOs who excel at these capabilities, and ones that don’t.

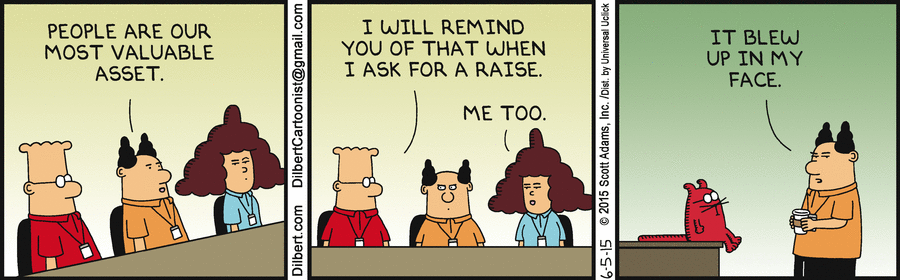

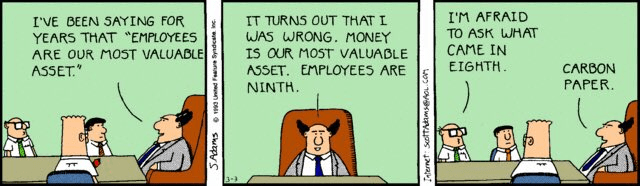

The reporting relationship reveals less about the individual executive, and more about how the system views its medical group: less as a strategic partner, and more as “an asset to feed the [hospital] mothership.” Or worse, as a high-cost asset that is underperforming, with the CFO brought in as a “fixer”, taking over management of the physician group to “stop the bleed.”

Ideally the medical group would be led by a senior physician leader, often with the title of chief clinical officer or chief physician executive, who has oversight of all of the system’s physician network relationships, and can coordinate work across all these entities, sitting at the highest level of the executive team, reporting to the CEO. Of course, these kinds of physician leaders—with executive presence, management acumen, respected by physician and executive peers—can be difficult to find.

Having a respected physician leader at the helm is even more important in a time of crisis, whether they lead alone or are paired with the CFO or another executive. Systems should have a plan to build the leadership talent needed to guide doctors through the coming clinical, generational, and strategic shifts in practice.