Category Archives: Uncategorized

This Type of Illiteracy Could Hurt You

More than half of older Americans lack the skills to gather and understand medical information. Providers must simplify, researchers say.

Every time her parents pick up a new prescription at a Walgreens in Houston, they follow Duyen Pham-Madden’s standing instructions: Use the iPad she bought for them, log onto FaceTime, hold up the pill bottles for her examination.

Her mother, 79, and father, 77, need numerous medications, but have trouble grasping when and how to take them.

The label may say to take one pill three times a day, but “my dad might take one a day,” said Ms. Pham-Madden, 56, an insurance purchasing agent in Blue Springs, Mo. “Or take three at a time.”

So she interprets the directions for them, also reminding her mother to take the prescribed megadose of vitamin D, for osteoporosis, only weekly, not daily.

Part of their struggle, Ms. Pham-Madden believes, stems from language barriers. The family emigrated from Vietnam in 1975, and while her parents speak and read English, they lack the fluency of native speakers.

But recently, Ms. Pham-Madden said, her father posed a question that anyone grappling with Medicare drug coverage might ask: “What’s the doughnut hole?”

Researchers refer to this type of knowledge as “health literacy,” meaning a person’s ability to obtain and understand the basic information needed to make appropriate health decisions.

Can someone read a pamphlet and then determine how often to undergo a particular medical test? Look at a graph and recognize a normal weight range for her height? Ascertain whether her insurance will cover a certain procedure?

Most American adults — 53 percent — have intermediate health literacy, a national survey found in 2006; they can perform “moderately challenging” activities, like reading denser texts and handling unfamiliar arithmetic.

Just 12 percent rank as “proficient,” the highest category. About a fifth have “basic” health literacy that could cause problems, and 14 percent score “below basic.” Health literacy differs by education level, race, poverty and other factors.

And it varies dramatically by age. While the proportion of adults with intermediate literacy ranges from 53 to 58 percent in other age groups, it falls to 38 percent among those 65 and older. The percentage of older adults with basic or below basic literacy is higher than in any other age group; only 3 percent qualify as proficient.

Why is that? Compared to younger groups, the current generation of “older adults were less likely to go beyond a high school education,” said Jennifer Wolff, a health services researcher at Johns Hopkins University.

Moreover, “as adults age, they’re more likely to experience cognitive impairment,” she pointed out, as well as hearing and vision loss that can affect their comprehension.

Consider the recent experience of a retired 84-year-old teacher. All her life, “she was very detail-oriented” and competent, said her daughter, Deborah Johnson, who lives in Lansing, Mich.

But a neurologist diagnosed mild cognitive impairment last summer and prescribed a drug intended to ameliorate its symptoms. It caused a frightening reaction — personality changes, lethargy, dizziness, sky-high blood pressure.

Ms. Johnson thinks her mother might have overdosed. “She told me she thought, ‘This is going to fix me, and I’ll be O.K. So if I take more pills, I’ll be O.K. faster.’”

Yet health literacy can be particularly crucial for seniors. They’re usually coping with more complicated medical problems, including multiple chronic diseases, an array of drugs, a host of specialists. They have more instructions to decipher, more tests to schedule, more decisions to ponder.

Low health literacy makes those tasks more difficult, with troubling results. Studies indicate that people with low literacy have poorer health at higher cost. They’re less likely to take advantage of preventive tests and immunizations, and more apt to be hospitalized.

It may not help much that future cohorts of older adults will be better educated. “The demands of interacting with the health care system are increasing,” Dr. Wolff said. “Ask any adult child of a parent who’s been hospitalized. The system has gotten increasingly complex.”

That doesn’t mean patients deserve all the blame for misunderstandings and snafus. Rima Rudd, a longtime health literacy researcher at Harvard University, has persistently criticized the communications skills of health institutions and professionals.

“We give people findings and tell them about risk and expect people to make decisions based on those concepts, but we don’t explain them very well,” she said. “Are our forms readable? Are the directions after surgery written coherently? If it’s written in jargon, with confusing words and numbers, you won’t get the gist of it and you won’t get important information.”

A few years ago, Steven Rosen, 64, had spent more than two months at a Chicago hospital after several surgeries. Then a social worker came into his room and told his wife Dorothy, “You have to move him tomorrow to an L.T.A.C.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Ms. Rosen recalled saying. “What’s an L.T.A.C.?”

Question: Was she demonstrating inadequate health literacy, or should the social worker have clarified that L.T.A.C.s — long-term acute care hospitals — provide more care than nursing homes for very ill patients?

Aware of such issues, health care organizations are scrambling to try to make information more accessible and intelligible, and to help patients of all ages understand an often bewildering environment.

They’re hiring squadrons of care coordinators and navigators (sometimes too many), and redesigning and rewriting pamphlets and forms. They’re teaching medical students to communicate more clearly and to encourage patients’ questions.

They’re turning to technology, like secure websites where both patients and family members can see test results or ask questions.

“It’s not the silver bullet we hoped for,” said Amy Chesser, a health communications researcher at Wichita State University, pointing out that many patients are reluctant to turn to provider websites. But the potential remains.

For now, though, often the primary health literacy navigators for older people are their adult children, most commonly daughters and daughters-in-law.

“In the best of all worlds, she’d just be the daughter,” Dr. Chesser said. “But we need her to serve other roles — being an advocate, asking a lot of questions of the provider, asking where to go for information, talking about second opinions.”

The current cohort of people over 70 grew up in a more patriarchal medical system and asking fewer questions, Dr. Wolff pointed out. Her research shows that while most seniors manage their own health care, about a third prefer to co-manage with family or close friends, or to delegate health matters to family or doctors.

Duyen Pham-Madden plays the co-managerial role from hundreds of miles away, keeping spreadsheets of her parents’ drugs, compiling lists of questions for doctors’ appointments, texting photos to pharmacists when the pills in a refilled prescription look different from the last batch.

She’d probably score well in health literacy, but “sometimes even I get mixed up,” she said.

What’s the Medicare doughnut hole? “I had to look it up,” she said. Once she did, she wondered, “How do they expect seniors to understand this?”

Up To A Third Of Knee Replacements Pack Pain And Regret

Danette Lake thought surgery would relieve the pain in her knees.

The arthritis pain began as a dull ache in her early 40s, brought on largely by the pressure of unwanted weight. Lake managed to lose 200 pounds through dieting and exercise, but the pain in her knees persisted.

A sexual assault two years ago left Lake with physical and psychological trauma. She damaged her knees while fighting off her attacker, who had broken into her home. Although she managed to escape, her knees never recovered. At times, the sharp pain drove her to the emergency room. Lake’s job, which involved loading luggage onto airplanes, often left her in misery.

When a doctor said that knee replacement would reduce her arthritis pain by 75 percent, Lake was overjoyed.

“I thought the knee replacement was going to be a cure,” said Lake, now 52 and living in rural Iowa. “I got all excited, thinking, ‘Finally, the pain is going to end and I will have some quality of life.’”

But one year after surgery on her right knee, Lake said she’s still suffering.

“I’m in constant pain, 24/7,” said Lake, who is too disabled to work. “There are times when I can’t even sleep.”

Most knee replacements are considered successful, and the procedure is known for being safe and cost-effective. Rates of the surgery doubled from 1999 to 2008, with 3.5 million procedures a year expected by 2030.

But Lake’s ordeal illustrates the surgery’s risks and limitations. Doctors are increasingly concerned that the procedure is overused and that its benefits have been oversold.

Research suggests that up to one-third of those who have knees replaced continue to experience chronic pain, while 1 in 5 are dissatisfied with the results. A study published last year in the BMJ found that knee replacement had “minimal effects on quality of life,” especially for patients with less severe arthritis.

One-third of patients who undergo knee replacement may not even be appropriate candidates for the procedure, because their arthritis symptoms aren’t severe enough to merit aggressive intervention, according to a 2014 study in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

“We do too many knee replacements,” said Dr. James Rickert, president of the Society for Patient Centered Orthopedics, which advocates for affordable health care, in an interview. “People will argue about the exact amount. But hardly anyone would argue that we don’t do too many.”

Although Americans are aging and getting heavier, those factors alone don’t explain the explosive growth in knee replacement. The increase may be fueled by a higher rate of injuries among younger patients and doctors’ greater willingness to operate on younger people, such as those in their 50s and early 60s, said Rickert, an orthopedic surgeon in Bedford, Ind. That shift has occurred because new implants can last longer — perhaps 20 years — before wearing out.

Yet even the newest models don’t last forever. Over time, implants can loosen and detach from the bone, causing pain. Plastic components of the artificial knee slowly wear out, creating debris that can cause inflammation. The wear and tear can cause the knee to break. Patients who remain obese after surgery can put extra pressure on implants, further shortening their lifespan.

The younger patients are, the more likely they are to “outlive” their knee implants and require a second surgery. Such “revision” procedures are more difficult to perform for many reasons, including the presence of scar tissue from the original surgery. Bone cement used in the first surgery also can be difficult to extract, and bones can fracture as the older artificial knee is removed, Rickert said.

Revisions are also more likely to cause complications. Among patients younger than 60, about 35 percent of men need a revision surgery, along with 20 percent of women, according to a November article in the Lancet.

Yet hospitals and surgery centers market knee replacements heavily, with ads that show patients running, bicycling, even playing basketball after the procedure, said Dr. Nicholas DiNubile, a Havertown, Pa., orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine. While many people with artificial knees can return to moderate exercise — such as doubles tennis — it’s unrealistic to imagine them playing full-court basketball again, he said.

“Hospitals are all competing with each other,” DiNubile said. Marketing can mislead younger patients into thinking, “‘I’ll get a new joint and go back to doing everything I did before,’” he said. To Rickert, “medical advertising is a big part of the problem. Its purpose is to sell patients on the procedures.”

Rickert said that some patients are offered surgery they don’t need and that money can be a factor.

Knee replacements, which cost $31,000 on average, are “really crucial to the financial health of hospitals and doctors’ practices,” he said. “The doctor earns a lot more if they do the surgery.”

Ignoring Alternatives

Yet surgery isn’t the only way to treat arthritis.

Patients with early disease often benefit from over-the-counter pain relievers, dietary advice, physical therapy and education about their condition, said Daniel Riddle, a physical therapy researcher and professor at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

Studies show that these approaches can even help people with more severe arthritis.

In a study published in Osteoarthritis and Cartilage in April, researchers compared surgical and non-surgical treatments in 100 older patients eligible for knee replacement.

Over two years, all of the patients improved, whether they were offered surgery or a combination of non-surgical therapies. Patients randomly assigned to undergo immediate knee replacement did better, improving twice as much as those given combination therapy, as measured on standard medical tests of pain and functioning.

But surgery also carried risks. Surgical patients developed four times as many complications, including infections, blood clots or knee stiffness severe enough to require another medical procedure under anesthesia. In general, 1 in every 100 to 200 patients who undergo a knee replacement die within 90 days of surgery.

Significantly, most of those treated with non-surgical therapies were satisfied with their progress. Although all were eligible to have knee replacement later, two-thirds chose not to do it.

Tia Floyd Williams suffered from painful arthritis for 15 years before having a knee replaced in September 2017. Although the procedure seemed to go smoothly, her pain returned after about four months, spreading to her hips and lower back.

She was told she needed a second, more extensive surgery to put a rod in her lower leg, said Williams, 52, of Nashville.

“At this point, I thought I would be getting a second knee done, not redoing the first one,” Williams said.

Other patients, such as Ellen Stutts, are happy with their results. Stutts, in Durham, N.C., had one knee replaced in 2016 and the other replaced this year. “It’s definitely better than before the surgery,” Stutts said.

Making Informed Decisions

Doctors and economists are increasingly concerned about inappropriate joint surgery of all types, not just knees.

Inappropriate treatment doesn’t harm only patients; it harms the health care system by raising costs for everyone, said Dr. John Mafi, an assistant professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

The 723,000 knee replacements performed in 2014 cost patients, insurers and taxpayers more than $40 billion. Those costs are projected to surge as the nation ages and grapples with the effects of the obesity epidemic, and an aging population.

To avoid inappropriate joint replacements, some health systems are developing “decision aids,” easy-to-understand written materials and videos about the risks, benefits and limits of surgery to help patients make more informed choices.

In 2009, Group Health introduced decision aids for patients considering joint replacement for hips and knees.

Blue Shield of California implemented a similar “shared decision-making” initiative.

Executives at the health plan have been especially concerned about the big increase in younger patients undergoing knee replacement surgery, said Henry Garlich, director of health care value solutions and enhanced clinical programs.

The percentage of knee replacements performed on people 45 to 64 increased from 30 percent in 2000 to 40 percent in 2015, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Because the devices can wear out in as little as a few years, a younger person could outlive their knees and require a replacement, Garlich said. But “revision” surgeries are much more complicated procedures, with a higher risk of complications and failure.

“Patients think after they have a knee replacement, they will be competing in the Olympics,” Garlich said.

Danette Lake once planned to undergo knee replacement surgery on her other knee. Today, she’s not sure what to do. She is afraid of being disappointed by a second surgery.

Sometimes, she said, “I think, ‘I might as well just stay in pain.’

Short-Term Health Plans Hold Savings For Consumers, Profits For Brokers And Insurers

Sure, they’re less expensive for consumers, but short-term health policies have another side: They’re highly profitable for insurers and offer hefty sales commissions.

Driven by rising premiums for Affordable Care Act plans, interest in short-term insurance is growing, boosted by Trump administration actions to ease Obama-era restrictions and possibly make federal subsidies available to consumers to purchase them.

That’s good news for brokers, who often see commissions on such policies hit 20 percent or more.

On a policy costing $200 a month, for example, that could translate to a $40 payment each month. By contrast, ACA plan commissions, which are often flat dollar amounts rather than a percentage of premium, can range from zero to $20 per enrollee per month.

“Customers are paying less and I’m making more,” said Cindy Holtzman, a broker in Woodstock, Ga., who said she gets 20 percent on short-term plan commissions.

Large online brokers also are eagerly eyeing the market.

Ehealth, one such firm, will “continue to shift our focus to selling short-term plans and non-ACA insurance packages,” CEO Scott Flanders told investors in October. The firm saw an 18 percent annual jump in enrollment in short-term plans this year, he added.

Insurers, too, see strong profits from plans because they generally pay out very little toward medical care when compared with the more comprehensive ACA plans.

Still, some agents like Holtzman have mixed feelings about selling the plans, because they offer skimpier coverage than ACA insurance. One 58-year-old client of Holtzman’s wanted one, but he had health problems. She also learned his income qualified him for an ACA subsidy, which currently cannot be used to purchase short-term coverage.

“There’s no way I would have considered a short-term plan for him,” she said. “I found him an ACA plan for $360 a month with a reduced deductible.” (A federal district court judge in Texas issued a ruling Dec. 14 striking down the ACA, which would among other things impact the requirements of ACA coverage and subsidies. The decision is expected to face appeal.)

Short-term plans can be far less expensive than ACA plans because they set annual or lifetime payment limits. Most exclude people with medical conditions, they often don’t cover prescription drugs, and policies exclude in fine print some conditions or treatments. Injuries sustained in school sports programs, for example, often are not covered. (These plans can be purchased at any time throughout the year, which is different than plans sold through the federal marketplaces. The open enrollment period for those ACA plans in most states ends Dec. 15.)

Consequently, insurers providing short-term plans don’t have to pay as many medical bills, so they have more money left over for profits. In forms filed with state regulators, Independence American Insurance Co. in Ohio shows it expects 60 percent of its premium revenue to be spent on its enrollees’ medical care. The remaining 40 percent can go to profits, executive salaries, marketing and commissions.

A 2016 report from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners showed that, on average, short-term plans paid out about 67 percent of their earnings on medical care.

That compares with ACA plans, which are required under the law to spend at least 80 percent of premium revenue on medical claims.

Short-term plans have long been sold mainly as a stopgap measure for people between jobs or school coverage. While exact figures are not available, brokers say interest dropped when the ACA took effect in 2014 because many people got subsidies to buy ACA plans and having a short-term plan did not exempt consumers from the law’s penalty for not carrying insurance.

But this year it ticked up again after Congress eliminated the penalty for 2019 coverage. At the same time, the premiums for ACA plans rose on average more than 30 percent.

“If I don’t want someone to walk out of the office with nothing at all because of cost, that’s when I will bring up short-term plans,” said Kelly Rector, president of Denny & Associates, an insurance sales brokerage in O’Fallon, a suburb of St. Louis. “But I don’t love the plans because of the risk.”

The Obama administration limited short-term plans to 90-day increments to reduce the number of younger or healthier people who would leave the ACA market. That rule, the Trump administration complained, forced people to reapply every few months and risk rejection by insurers if their health had declined.

This summer, the administration finalized new rules allowing insurers to offer short-term plans for up to 12 months — and gave them the option to allow renewals for up to three years. States can be more restrictive or even bar such plans altogether.

Administration officials estimate short-term plans could be half the cost of the more comprehensive ACA insurance and draw 600,000 people to enroll in 2019, with 100,000 to 200,000 of those dropping ACA coverage to do so.

And recent guidance to states says they could seek permission to allow federal subsidies to be used for short-term plans. Currently, those subsidies apply only to ACA-compliant plans.

Granting subsidies for short-term plans “would mean tax dollars are not only subsidizing commissions, but also executive salaries and marketing budgets,” said Sabrina Corlette of Georgetown University Center on Health Insurance Reforms.

No state has yet applied to do that.

For now, brokers are focusing on getting their clients into some kind of coverage for next year. Commissions on both ACA and short-term plans are getting their attention.

After several years of declining commissions for ACA plans — with some carriers cutting them altogether a couple of years ago — brokers say they are seeing a bit of a rebound.

Among Colorado ACA insurers, “it’s gone from about $14 to $16 per enrollee [a month] to $16 to $18,” said Louise Norris, a health policy writer and co-owner of an insurance brokerage.

Rector, in Missouri, said an insurer that last year paid no commissions has reinstated them for 2019 coverage. For her, that doesn’t really matter, she said, because once carriers started reducing or eliminating commissions, she began charging clients a flat rate to enroll.

Norris noted that some states changed their laws so brokers could do just that.

At least one state, Connecticut, ruled that insurers had to pay a commission, which she thinks is protective for consumers.

“Insurance regulators need to step in and make sure brokers are getting paid,” said Norris, or some brokers, “out of necessity,” might steer people to higher-commission products, such as short-term plans, that might not be the best answer for their clients.

Her agency does not sell short-term or some other types of limited-benefit plans.

“I don’t want to have a client come back and say I’ve had a heart attack and have all these unpaid bills,” she said.

Misconceptions About Health Costs When You’re Older

Some significant expenses decline as we age: Most mortgages are eventually paid off, and ideally children grow up and become self-supporting.

But health care is one area in which costs are almost certain to rise. After all, one of the original justifications for Medicare — which kicks in at age 65 — is that older people have much higher health care needs and expenses.

But there are a few common misunderstandings about health costswhen people are older, including the idea that money can easily be saved by reducing wasteful end-of-life spending.

No, Medicare won’t cover it all. There are gaps.

Half our lifetime spending on health care is in retirement, even though that represents only about 20 percent of a typical life span. Total health care spending for Americans 65 and older is about $15,000 per year, on average, nearly three times that of working-age Americans.

Don’t expect Medicare to provide complete protection from these expenses.

Traditional Medicare has substantial gaps, leaving Americans on the hook for a lot more than they might expect. It has no cap on how much you can pay out of pocket, for example. Such coverage gaps can be filled — at least in part — by other types of insurance. But some alternatives, such as Medicare Advantage, aren’t accepted by as many doctors or hospitals as accept traditional Medicare.

On average, retirees directly pay for about one-fifth of their total health care spending. Some spend much more.

One huge expense no Medicare plans cover is long-term care in a nursing home.

Over half of retirement-age adults will eventually need long-term care, which can cost as much as $90,000 per year at a nursing home. Although most who enter a nursing home don’t stay long, 5 percent of the population stays for more than four years. You can buy separate coverage outside the Medicare program for this, but the premiums can be high, especially if you wait until near retirement to buy.

Medicaid plays a bigger role than expected

Although Medicare is thought of as the source of health care coverage for retirees, Medicaid plays a crucial role.

Medicaid, the joint federal-state heath financing program for low-income people, has long been the nation’s main financial backstop for long-term care. Over 60 percent of nursing home residents have Medicaid coverage, and over half of the nation’s long-term care is funded by the program.

That isn’t because most people who require long-term care have low incomes. It’s because long-term care is so expensive that those needing it can frequently deplete their financial resources and then must turn to Medicaid.

A recent working paper from the National Bureau of Economic found that, on average, Medicaid covers 20 percent of retiree health spending. The figure is larger for lower-income retirees, who are more likely to qualify for Medicaid for more of their retirement years.

It’s really hard to predict when someone will die

A widely held view is that much spending is wasted on “heroic” measures taken at the end of life. Are all the resources devoted to Medicare and Medicaid really necessary?

First, let’s get one misunderstanding out of the way. The proportion of health spending at the end of life in the United States is lower than in many other wealthy countries.

Still, it’s a tempting area to look for savings. Only 5 percent of Medicare beneficiaries die each year, but 25 percent of all Medicare spending is on individuals within one year of death. However, the big challenge in reducing end-of-life spending, highlighted by a recent study in Science, is that it is hard to know which patients are in their final year.

The study used all the data available from Medicare records to make predictions: For each beneficiary, it assigned a probability of death within a year. Of those with the very highest probability of dying — the top 1 percent — fewer than half actually died.

“This shows that it’s just very hard to know in advance who will die soon with much certainty,” said Amy Finkelstein, an M.I.T. economist and an author of the study. “That makes it infeasible to make a big dent in health care spending by cutting spending on patients who are almost certain to die soon.”

That does not mean that all the care provided to dying patients — or to any patient — is valuable. Another study finds that high end-of-life spending in a region is closely related to the proportion of doctors in that region who use treatments not supported by evidence — in other words, waste.

“People at high risk of dying certainly require more health care,” said Jonathan Skinner, an author of the study and a professor of economics at Dartmouth. “But why should some regions be hospitalizing otherwise similar high-risk patients at much higher rates than other regions?”

In 2014, for example, chronically ill Medicare beneficiaries in Manhattan spent 73 percent more days in the hospital in their last two years of life than comparable beneficiaries in Rochester.

“There absolutely is waste in the system,” said Ashish Jha, director of the Harvard Global Health Institute. But, he argues, waste is present throughout the life span, not just at the end of life: “We have confused that spending as end-of-life spending is somehow wasteful. But that’s not right because we are terrible at predicting who is going to die.”

Of course, beyond any statistical analysis, there are actual people involved, and wrenching individual decisions that need to be made.

“We should do all we can to push waste out of the system,” Dr. Jha said. “But spending more money on people who are suffering from an illness is appropriate, even if they die.”

DOJ recovered $2.5 billion in 2018 healthcare false claim cases

DOJ recovered $2.5 billion in 2018 healthcare false claim cases

According to the DOJ, this is the ninth consecutive year that the organizations’ civil healthcare fraud settlements and judgments have exceeded $2 billion.

As part of the federal government’s increasing focus on issues of healthcare fraud, particularly in the Medicare space, the U.S. Department of Justice recovered $2.5 billion in settlements and judgments from False Claims Act Cases over the past year.

According to the DOJ, this is the ninth consecutive year that the organizations’ civil health care fraud settlements and judgments have exceeded $2 billion.

While the $2.5 billion number represents federal losses, the DOJ also said it also helped recover significant funds for state Medicaid programs

“Every year, the submission of false claims to the government cheats the American taxpayer out of billions of dollars,” Principal Deputy Associate Attorney General Jesse Panuccio said in a statement.

“In some cases, unscrupulous actors undermine federal healthcare programs or circumvent safeguards meant to protect the public health … The nearly three billion dollars recovered by the Civil Division represents the Department’s continued commitment to fighting fraudsters and cheats on behalf of the American taxpayer.”

The False Claims Act has its roots in groups trying to defraud the military during and after the Civil War and was significantly strengthened since 1986 when Congress increased incentives for whistleblowers to file lawsuits alleging false claims.

In healthcare, organizations across the industry were hit with False Claims cases including drug companies, medical device manufacturers, payer organizations and healthcare providers.

The single largest recovery over the past year was a $625 million settlement paid by drug wholesaler AmerisourceBergen to resolve a number of claims including that the company illegally repackaged injectable cancer drugs into pre-filled syringes and billing multiple doctors for individual drug vials.

The DOJ also brought cases against drug companies who increased drug prices by funding Medicare co-payments meant to serve as a check on healthcare costs.

In one instance, United Therapeutics Corporation paid $210 million over allegations that it illegally used a foundation to funnel co-pay obligations for Medicare patients taking its drugs. Pfizer paid nearly $24 million in a similar case, with the government alleging that the company raised the price of a cardiac drug called Tikosy by 40 percent over three months

One major case against Massachusetts-based medical device company Alere resulted in a $33.2 million settlement over allegations that it sold unreliable diagnostic devices meant to detect acute coronary syndromes, heart failure, drug overdose and other serious conditions.

On the provider side, the DOJ recovered $270 million from DaVita subsidiary HealthCare Partners Holdings for upcoding and providing inaccurate information to inflate Medicare Advantage payments.

Another major case was against former health system Health Management Associates which allegedly engaged in major Medicare fraud including illegal kickbacks to physicians for referrals, incorrect billing for observation and outpatient services and inflated facility fees.

When it comes to health plans, the government’s case against UnitedHealth Group over allegations that it knowingly obtained inflated risk adjustment payments for its Medicare Advantage beneficiaries is still ongoing.

Have enough beds? Demographic trends paint an alarming picture

Have enough beds? Demographic trends paint an alarming picture

Healthcare providers know that inpatient volumes are down over historic levels. (But let’s not talk […]

Healthcare providers know that inpatient volumes are down over historic levels. (But let’s not talk about emergency department volumes—those are WAY up.) They know this trend originates mostly with Medicare beneficiaries. They also know the causes: migration to outpatient services, observation day rules, intense focus on decreasing length of stay, and reduced readmissions as part of their quality initiatives.

What they may miss, however, is that this trend also has something to do with the declining average age of our nation’s senior population—a phenomenon that first began in 2005 and will continue until about 2020. In 2005, the average age of our nation’s senior population was 75.2 years; in 2020, the average age is expected to be 74.4 years.

This fact is important because older seniors consume significantly greater healthcare resources than younger seniors. Today, those over 65 represent about 15 percent of the total U.S. population. By 2020, one out of six Americans will be 65 or older, rising to 22 percent by 2040. Understanding how this population is distributed among age cohorts is critically important not only in understanding current trends in reduced utilization, but also in preparing for the future.

Taking a Closer Look

This increasing proportion of the population that are seniors is important because the average Medicare beneficiary consumes about four times the hospital-based services as the average commercially insured person. But it is just as important to look more closely at consumption patterns within the senior population. Those between ages 75 and 84 consume about 60 percent more services than seniors ages 65 to 74. Those age 85 and above consume about two-and-a-half times as much.

According to U.S. Census forecasts, in 2021, the over-75 population will make up the lowest percentage of the senior Medicare population in recent history, at about 41 percent. By 2040, seniors older than 75 will constitute 55 percent of the total senior population. This fact alone would suggest that we are in for a reversal of declining volume patterns—but by how much?

The answer is that if nothing is done to further reduce admissions and days per 1,000 for the senior Medicare population, inpatient days should almost double from about 70 million today to about 130 million in 2040 on the basis of demographic changes alone. That represents a need for some 220,000 additional beds at 75 percent capacity by 2040—never mind all the other healthcare services that will be needed. But even as there is general recognition among healthcare leaders of the advent of an aging population, there is also the general sense that somehow, we will not need the same level of resources to meet that demand as we do today.

Where does that sense of assurance come from? Apparently, it stems from the belief that unnecessary and excess utilization exists purely due to financial reasons, and that even more of the care delivered on an inpatient basis could be performed on an outpatient basis or at home with better monitoring and intervention through new technologies. But there also appears to be an ignoring of the well-known trend for the population becoming increasingly co-morbid at ever-younger ages. Additionally, some believe that increased focus on addressing social determinants of health, which impact 64 percent of health outcomes, will reduce need for medical services.

All of these assumptions may be true, in theory. In practice, however, as a senior healthcare executive and registered nurse said to me recently, “People are really sick. You have no idea.” There is also the enormous question of how one staffs and gets paid for programs and investments that might reduce demand for hospital-based services. The economics of today’s medicalized approach to health care is unprepared to address this.

A Critical Issue for Leadership

This is an issue that should be of paramount importance to healthcare providers. As seniors comprise a greater portion of our population, demand for inpatient and post-acute services will significantly increase. The hope and dream expressed in the view that hospital-based utilization might be reduced springs from a terrible reality: Hospitals in general, with the possible exception of high-end tertiary/quaternary services, lose money on government-reimbursed volume—and this will only get worse as cost inflation continues to exceed government reimbursement trends.

The prospect of the demand for inpatient days nearly doubling over the next 20 years paints a horrifying financial picture. Who, then, would not want to hope that something magical will happen to prevent a scenario that logic and data tell us is likely to occur?

It’s time for healthcare leaders to take a hard look at the trends around senior aging and have tough discussions with their executive teams and boards about the impact these trends could have on their organizations’ futures—and what they should be doing now to prepare.

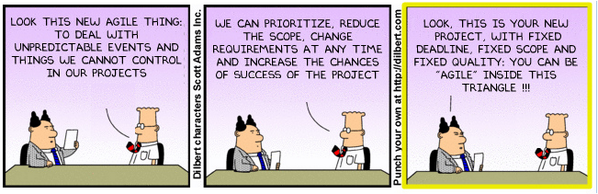

Cartoon – Preventive Medicine