Category Archives: 2024 Election Issues

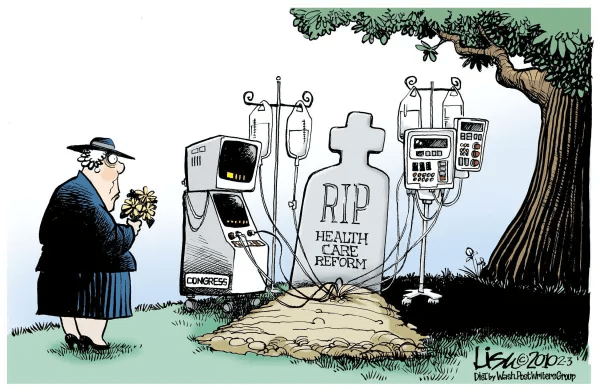

Cartoon – RIP Healthcare Reform

Sweeping health reform takes a back seat for this election cycle

https://mailchi.mp/79ecc69aca80/the-weekly-gist-december-15-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

After a presentation this week, a senior physician from the audience of our member health systems reached out to discuss a well-trod topic, the future of health reform legislation. But his question led to a more forward-looking concern:

“You talked very little about politics, even though we have an election coming up next year. Are you anticipating that Medicare for All will come up again? And what would the impact be on doctors?”

As we’ve discussed before, we think it’s unlikely that sweeping health reform legislation like Medicare for All (M4A) would make its way through Congress, even if Democrats sweep the 2024 elections—and it’s far too early for health systems to dedicate energy to a M4A strategy.

Healthcare is not shaping up to be a campaign priority for either party, and given the levels of partisan division and expectations that slim majorities will continue, passing significant reform would be highly unlikely.

Although there is bipartisan consensus around a limited set of issues like increasing transparency and limiting the power of PBMs, greater impact in the near term will come from regulatory, rather than legislative, action.

For instance, health systems are much more exposed by the push toward site-neutral payments. How large is the potential hit? One mid-sized regional health system we work with estimated they stand to lose nearly $80M of annual revenue if site-neutral payments are fully implemented—catastrophic to their already slim system margins.

Preparing for this inevitable payment change or the long-term possibility of M4A both require the same strategy: serious and relentless focus on cost reduction.

This still leaves a giant elephant in the room: the long-term impact on the physician enterprise.

As referral-based economics continue to erode, health systems will find it increasingly difficult to maintain current physician salaries, further driving the need to move beyond fee-for-service toward a health system economic model based on total cost of care and consumer value, while building physician compensation around those shared goals.

The Affordable Care Act is Back on Stage: What to Expect

In the last 2 weeks, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has been inserted itself in Campaign 2024 by Republican aspirants for the White House:

- On Truth Social November 28, former President Trump promised to replace it with something better: “Getting much better Healthcare than Obamacare for the American people will be a priority of the Trump Administration. It is not a matter of cost; it is a matter of HEALTH. America will have one of the best Healthcare Plans anywhere in the world. Right now, it has one of the WORST! I don’t want to terminate Obamacare, I want to REPLACE IT with MUCH BETTER HEALTHCARE. Obamacare Sucks!!!!”

- Then, on NBC’s Meet the Press December 3, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis offered “We need to have a healthcare plan that works,” Obamacare hasn’t worked. We are going to replace and supersede with a better plan….a totally different healthcare plan… big institutions that are causing prices to be high: big pharma, big insurance and big government.”

It’s no surprise. Health costs and affordability rank behind the economy as top issues for Republican voters per the latest Kaiser Tracking Poll. And distaste with the status quo is widespread and bipartisan: per the Keckley Poll (October 2023), 70% of Americans including majorities in both parties and age-cohorts under 65 think “the system is fundamentally flawed and needs major change.” To GOP voters, the ACA is to blame.

Background:

The Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare aka the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act) was passed into law March 23, 2013. It is the most sweeping and controversial health industry legislation passed by Congress since Lyndon Johnson’s Medicare and Medicaid Act (1965). Opinions about the law haven’t changed much in almost 14 years: when passed in 2010, 46% were favorable toward the law vs. 40% who were opposed. Today, those favorable has increased to 59% while opposition has stayed at 40% (Kaiser Tracking Poll).

Few elected officials and even fewer voters have actually read the law. It’s understandable: 955 pages, 10 major sections (Titles) and a plethora of administrative actions, executive orders, amendments and legal challenges that have followed. It continues to be under-reported in media and misrepresented in campaign rhetoric by both sides. Campaign 2024 seems likely to be more of the same.

In 2009, I facilitated discussions about health reform between the White House Office of Health Reform and the leading private sector players in the system (the American Medical Association, the American Hospital Association, America’s Health Insurance Plans, AdvaMed, PhRMA, and BIO). The impetus for these deliberations was the Obama administration’s directive that systemic reform was necessary with three-aims: reduce cost, increase access via insurance coverage and improve the quality of care provided by a private system. In parallel, key Committees in the House and Senate held hearings ultimately resulting in passage of separate House and Senate versions with the Senate’s becoming the substance of the final legislation. Think tanks on the left (I.e. the Center for American Progress et al.) and on the right (i.e. the Heritage Foundation) weighed in with members of Congress and DC influencers as the legislation morphed. And new ‘coalitions, centers and institutes’ formed to advocate for and against certain ACA provisions on behalf of their members while maintaining a degree of anonymity.

So, as the ACA resurfaces in political discourse in coming months, it’s important it be framed objectively. To that end, 3 major considerations are necessary to have a ‘fair and balanced’ view of the ACA:

1-The ACA was intended as a comprehensive health reform legislative platform. It was designed to be implemented between 2010 and 2019 in a private system prompted by new federal and state policies to address cost, access and quality. It allowed states latitude in implementing certain elements (like Medicaid expansion, healthcare marketplaces) but few exceptions in other areas (i.e.individual and employer mandates to purchase insurance, minimum requirements for qualified health plans, et al). The CBO estimated it would add $1.1 trillion to overall healthcare spending over the decade but pay for itself by reducing demand, administrative red-tape and leveraging better data for decision-making. The law included provisions to…

- To improve quality by modernizing of the workforce, creating an Annual Quality Report obligation by HHS, creating the Patient Centered Outcome Research Institute and expanding the the National Quality Forum, adding requirements that approved preventive care be accessible at no cost, expanding community health centers, increasing residency programs in primary care and general surgery, implementing comparative effectiveness assessments to enable clinical transparency and more.

- To increase access to health insurance by subsidizing coverage for small businesses and low income individuals (up to 400% of the Federal poverty level), funding 90% of the added costs in states choosing to expand their Medicaid enrollments for households earning up to 138% of the poverty level, extending household coverage so ‘young invincibles’ under 26 years of age could stay on their parent’s insurance plan, requiring insurers to provide “essential benefits” in their offerings, imposing medical loss ratio (MLR) mandates (80% individual, 85% group) and more.

- To lower costs by creating the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to construct 5-year demonstration pilots and value-based purchasing programs that shift provider incentives from volume to value, imposing price and quality reporting and transparency requirements and more.

The ACA was ambitious: it was modeled after Romneycare in MA and premised on the presumption that meaningful results could be achieved in a decade. But Romneycare (2006) was about near-universal insurance coverage for all in the Commonwealth, not the triple aim, and the resistance calcified quickly among special interests threatened by its potential.

2-The ACA passed at a time of economic insecurity and hyper-partisan rancor and before many of the industry’s most significant innovations had taken hold. The ACA was the second major legislation passed in the first term of the Obama administration (2009-2012); the first was the $831 billion American Recovery and Reconstruction Act (ARRA) stimulus package that targeted “shovel ready jobs” as a means of economic recovery from the 2008-2010 Great Recession. But notably, it included $138 billion for healthcare including requirements for hospitals and physicians to computerize their medical records, extension of medical insurance to laid off workers and additional funding for states to offset their Medicaid program expenses. The Obama-Biden team came to power with populist momentum behind their promises to lower health costs while keeping the doctors and insurance plans they had. Its rollout was plagued by miscues and the administration’s most popular assurances (‘keep your doctor and hospitals’) were not kept. The Republican Majority in the 111th Congress’ (247-193)) seized on the administration’s miss fueling anti-ACA rhetoric among critics and misinformation.

3-Support for the ACA has grown but its results are mixed. It has survived 7 Supreme Court challenges and more than 70 failed repeal votes in Congress. It enjoys vigorous support in the Biden administration and among the industry’s major trade groups but remains problematic to outsiders who believe it harmful to their interests. For example, under the framework of the ACA, the administration is pushing for larger provider networks in the 18 states and DC that run their own marketplaces, expanded dental and mental health coverage, extended open enrollment for Marketplace coverage and restoration of restrictions on “junk insurance’ but its results to date are mixed: access to insurance coverage has increased. Improvements in quality have been significant as a result of innovations in care coordination and technology-enabled diagnostic accuracy. But costs have soared: between 2010 and 2021, total health spending increased 64% while the U.S. population increased only 7%.

So, as the ACA takes center stage in Campaign 2024, here are 4 things to watch:

1-Media attention to elements of the ACA other than health insurance coverage. My bet: attention from critics will be its unanticipated costs in addition to its federal abortion protections now in the hands of states. The ACA’s embrace of price and quality transparency is of particular interest to media and speculation that industry consolidation was an unintended negative result of the law will energize calls for its replacement. Thus, the law will get more attention. Misinformation and disinformation by special interests about its original intent as a “government takeover of the health system” will be low hanging fruit for antagonists.

2- Changes to the law necessary intended to correct/mitigate its unintended consequences, modernize it to industry best practice standards and responses to court challenges will lend to the law’s complex compliance challenges for each player in the system. New ways of prompting Medicaid expansion, integration of mental health and social determinants with traditional care, the impact of tools like ChatGPT, quantum computing, generative AI not imagined as the law was built, the consequences of private equity investments on prices and spending, and much more.

3-Public confusion. The ACA is a massive law in a massive industry. Cliff’s Notes are accessible but opinions about it are rarely based on a studied view of its intent and structure. It lends itself to soundbites intended to obscure, generalize or misdirect the public’s attention.

4-The ACA price tag. In 2010, the CBO estimated its added cost to health spending at $1.1 trillion (2010-2019) but its latest estimate is at least $3 trillion for its added insurance subsidies alone. The fact is no one knows for sure what its costs are nor the value of the changes it has induced into the health system. The ranks of those with insurance coverage has been cut in half. Hospitals, physicians, post-acute providers, drug manufacturers and insurers are implementing value-based care strategies and price transparency (though reluctantly) but annual health cost increases have consistently exceeded 4% annually as the cumulative impact of medical inflation, utilization, consolidation and price increases are felt.

Final thought:

I have studied the ACA, and the enabling laws, executive orders, administrative and regulatory actions, court rulings and state referenda that have followed its passage. Despite promises to ‘repeal and replace’ by some, it is more likely foundational to bipartisan “fix and repair’ regulatory reforms that focus more attention to systemness, technology-enabled self-care, health and wellbeing and more.

It will be interesting to see how the ACA plays in Campaign 2024 and how moderators for the CNN-hosted debates January 10 in Des Moines and January 21 in New Hampshire address it. In the 2-hour Tuscaloosa debate last Wednesday, it was referenced in response to a question directed to Gov. DeSantis about ‘reforming the system’ 101 minutes into the News Nation broadcast. It’s certain to get more attention going forward and it’s certain to play a more prominent role in the future of the system.

The ACA is back on the radar in U.S. healthcare. Stay tuned.

PS The resignations under pressure of Penn President Elizabeth Magill and Board Chair Scott Bok over inappropriate characterization of Hamas’ genocidal actions toward Jews are not surprising. Her response to Congressional questioning was unfortunate. The eventuality turned in 4 days, sparked by student outrage and adverse media attention that tarnished the reputations of otherwise venerable institutions like Penn, MIT and Harvard.

The lessons for every organization, including the big names in healthcare, are not to be dismissed: Beyond the issues of genocide, our industry is home to a widening number of incendiary issues like Hamas.

They’re increasingly exposed to public smell tests that often lead to more: Workforce strikes. CEO compensation. Fraud and abuse. Tax exemptions and community benefits. Prior authorization and coverage denial. Corporate profit. Patient collection and benevolent use policies. Board independence and competence and many more are ripe for detractors and activist seeking attention.

Public opinion matters. Reputations matter. Boards of Directors are directly accountable for both.

Do We Still Care About the Uninsured?

Were you better off in 2022 than you were in 2017? I was for a lot of reasons. One thing that didn’t change over those five years, though, was my health insurance status. I had health insurance in 2017, and I had health insurance in 2022. And I still have health insurance today.

So do most Americans. In fact, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s latest report on health insurance coverage in the U.S., 92.1% of us had some form of health insurance in 2022. That’s about 304 million people, per the report.

Conversely, 7.9% of us were uninsured last year. That’s a little more than 25.9 million people. That’s down from 8.3% and about 27.2 million people in 2021.

Some may see the decrease in both the percentage and number of uninsured as good news. And it is. Any time the uninsured figures go down, that’s good.

The bad news is, we’re back where we were in 2017. That’s also when 7.9% of us, or about 25.6 million people, were uninsured. Five years of trying to get more people insured and nothing to show for it.

The number of people with any type of private health insurance (employer-based or direct-purchase) crept up to 216.5 million last year from 216.4 million in 2021. The number of people with any type of public health insurance (Medicare, Medicaid, etc.) rose to 119.1 million last year from 117.1 million in 2021. Both headed in the right direction but too slow to push the uninsured rate significantly down.

If we want to get serious about achieving universal coverage, let’s get serious about it. If we don’t want to get serious about it because most of us already have health insurance, the only useful purpose of the Census Bureau’s annual reports on health insurance is to show us how little we really care.

Thanks for reading.

To learn more about this topic, please read:

How Do Democrats and Republicans Rate Healthcare for 2024?

It feels as though November 5, 2024 is far away, but for both Democrats and Republicans, the election is now. On the issue of healthcare, the two parties’ approaches differ sharply.

Think back to the behemoth effort by Republicans to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act six years ago, an effort that left them floundering for a replacement, basically empty-handed. Recall the 2022 midterms, when their candidates in 10 of the tightest House and Senate races uttered hardly a peep about healthcare.

That reticence stood in sharp contrast to Democrats who weren’t shy about reiterating their support for abortion rights, simultaneously trying hard to ensure that Americans understood and applauded healthcare tenets in the Inflation Reduction Act.

As The Hill noted in early August, sounds like the same thing is happening this time around as America barrels toward November 2024. The publication said it reached to 10 of the leading Republican candidates about their plans to reduce healthcare costs and make healthcare more affordable, and only one responded: Rep. Will Hurd (R-Texas).

Healthcare ‘A Very Big Problem’

Maybe the party thinks its supporters don’t care. But, a Pew Research poll from June showed 64% of us think healthcare affordability is a “very big problem,” superseded only by inflation. In that research, 73% of Democrats and 54% of Republicans thought so.

Chuck Coughlin, president and CEO of HighGround, an Arizona-based public affairs firm, told The Hill that the results aren’t surprising.

“If you’re a Republican, what are you going to talk about on healthcare?” he said.

Observers note that the party has homed in on COVID-lockdowns, transgender medical rights, and yes, abortion.

Republicans Champion CHOICE

There is action on this front, for in late July, House Republicans passed the CHOICE Arrangement Act. Its future with the Democratic-controlled Senate is bleak, but if Republicans triumph in the Senate and White House next year, it could advance with its focus on short-term health plans. They don’t offer the same broad ACA benefits and have a troubling list of “what we won’t cover” that feels like coverage is going backwards to some.

Plans won’t offer coverage for preexisting conditions, maternity care, or prescription drugs, and they can set limits on coverage. The plans will make it easier for small employers to self-insure, so they don’t have to adhere to ACA or state insurance rules.

CHOICE would let large groups come together to buy Association Health Plans, said NPR, which noted that in the past, there have been “issues” with these types of plans.

Insurance experts say that the act takes a swing at the very foundation of the ACA. As one analyst described it, the act intends to improve America’s healthcare “through increased reliance on the free market and decreased reliance on the federal government.”

Democrats Tout Reduce-Price Prescriptions

Meanwhile, on Aug. 29, President Joe Biden spoke proudly in The White House: “Folks, there’s a lot of really great Republicans out there. And I mean that sincerely…But we’ll stand up to the MAGA Republicans who have been trying for years to get rid of the Affordable Care Act and deny tens of millions of Americans access to quality, affordable healthcare.”

Current ACA enrollment is higher than 16 million.

He said that Big Pharma charges Americans more than three times what other countries charge for medications. And on that date, he announced that “the (Inflation Reduction Act) law finally gave Medicare the power to negotiate lower prescription drug prices.” He wasn’t shy about saying that this happened without help from “the other team.”

The New York Times said it feels this push for lower healthcare costs will be the centerpiece of his re-election campaign. The announcement confirmed that his administration will negotiate to lower prices on 10 popular—and expensive drugs—that treat common chronic illnesses.

It said previous research shows that as many as 80% of Americans want the government to have the power to negotiate.

The president also said that “Next year, Medicare will select more drugs for negotiation.” He added that his administration “is cracking down on junk health insurance plans that look like they’re inexpensive but too often stick consumers with big hidden fees.” And it’s tackling the extensive problem of surprise medical bills.

Earlier, on August 11, Biden and fellow Democrats celebrated the first anniversary of the PACT Act, legislation that provides healthcare to veterans exposed to toxic burn pits while serving. He said more than 300,000 veterans and families have received these services, with more than 4 million screened for toxic exposure conditions.

Push for High-Deductible Plans

Republicans want to reduce risk of high-deductible plans and make them more desirable—that responsibility is on insurers. According to Politico, these plans count more than 60 million people as members, and feature low premiums and tax advantages. The party said plans will also help lower inflation when people think twice about seeking unneeded care.

The plans’ low monthly premiums offer comprehensive preventive care coverage: physicals, vaccinations, mammograms, and colonoscopies, and have no co-payments, Politico said. The “but” in all this is that members will pay their insurers’ negotiated rate when they’re sick, and for medicines and surgeries. Minimum deductible is $1,500 or $3,000 for families—and can be even higher.

Members can fund health savings accounts but can’t fund flexible spending accounts.

Proponents cite more access to care, and reduced costs due to promotion of preventive care. Nay-sayers worry about lower-income members facing costly bills due to insufficient coverage.

Republican Candidates Diverge on Medicaid

The American Hospital Association (AHA) doesn’t love these high deductible plans. It explained that members “find they can’t manage the gap between what their insurance pays and what they themselves owe as a result,” and that, AHA said, contributes to medical debt—something the association wants to change.

An Aug. 3 Opinion in JAMA Health Forum pointed out other ways the two parties diverge on healthcare. For example, the piece cited Biden’s incentives for Medicaid expansion. In contrast, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, a Republican presidential candidate, has not worked to offer Medicaid to all lower-income residents under the ACA. Former Governor Nikki Haley of South Carolina feels the same, doing nothing. However, former New Jersey Governor Chris Christie has expanded it, as did former Vice President Mike Pence, when he governed Indiana.

Undoubtedly, as in presidential elections past, healthcare will be at least a talking point, with Democrats likely continuing to make it a central focus, as before.

Healthcare System in Campaign 2024: Out of Sight, Out of Mind?

The GOP Presidential debate marked the unofficial start of the 2024 Presidential campaign. With the exception of continued funding for Ukraine, style points won over issue distinctions as each of the 8 White House aspirants sought to make the cut to the next debate September 27 at the Reagan Library in Simi Valley, CA.

For the candidates in Milwaukee, it’s about “Stayin’ Alive” per the BeeGee’s hit song: that means avoiding self-inflicted harm while privately raising money to keep their campaigns afloat. And, based on Debate One, with the exception of abortion, that means they’ll not face questions about their positions on the litany of issues that dominate healthcare these days i.e., drug prices, hospital consolidation, price transparency, workforce burnout and many others. In Milwaukee, healthcare was essentially ‘out of sight our of mind’ to the moderators and debaters despite being 18% of the U.S. economy and its biggest employer.

For now, each will enlist ghostwriters to produce position papers for their websites, and, on occasion, reporters will press for specifics to test their grasp on a topic but that’s about it. Based on last Wednesday’s 2-hour event, it’s unlikely general media outlets like Fox News (which also hosts Debate Two) will explore healthcare issues except for abortion.

That means healthcare will be subordinated to the economy, inflation, immigration and crime—the top issues to GOP voters—for most of the Presidential primary season.

Next November, voters will also elect 34 US Senators, 435 members of the House of Representatives, 11 Governors and their representatives in 85 state legislative bodies. This will be the first election cycle after reapportionment of votes in the United States Electoral College following the 2020 United States census. Swing states (WI, MI, PA, NV, AZ, GA, FL, OH, CO, VA) will again be keys to the Presidential results since demographics and population shifts have increased the concentrations of each party’s core voters in so-called Blue States and Red States:

- The Democratic voter core is diverse, educated and culturally liberal with its strongest appeal to African-Americans, Latinos, women, educated professionals and urban voters. Blue States are predominantly in the Northeast, Upper Midwest and West Coast regions.

- The Republican voter core consists of rural white voters, evangelicals, the elderly, and non-college educated adults. Red States are predominantly in the South and Southwest.

The increased concentrations of Blue or Red voters in certain states and regions has contributed to political polarization in the U.S. electorate and presents an unusual challenge to healthcare. Per Gallup: “Political polarization since 2003 has increased most significantly on issues related to federal government power, global warming and the environment, education, abortion, foreign trade, immigration, gun laws, the government’s role in providing healthcare, and income tax fairness. Increased polarization has been less evident on certain moral issues and satisfaction with the state of race relations.”

Thus, healthcare issues are increasingly subject to hyper partisanship and often misinformation.

Given the limited knowledge voters have on most health issues and growing prevalence of social media fueled misinformation, political polarization creates echo chambers in healthcare—one that thinks the system works for those who can afford it and another that thinks that’s wrong.

It’s dicey for politicians: it’s political malpractice to offer specific solutions on anything, especially healthcare. It’s safer to attack its biggest vulnerabilities—affordability and equitable access—even though they mean something different in every echo chamber.

My take:

Barring a second Covid pandemic or global conflict with Russia/China, it’s unlikely healthcare issues will be prominent in Campaign 2024 at the national level except for abortion. At least through the May primary season, here’s the political landscape for healthcare:

Affordability and inequitable access will be the focus of candidate rhetoric at the national level: Trust and confidence in the U.S. health system has eroded. That’s fertile political turf for critics.

In Congress, the fiercest defenders of the status quo have joined efforts to impose restrictions on consolidation and price transparency for hospitals and price controls for prescription drugs. There’s Bipartisan acknowledgement that inequities in accessing care are significant and increasing, especially in minority and low income populations. They differ over the remedy. Employers expect their health costs to increase at least 8% next year and blame hospitals and drug companies for price gauging and want Congress to do more. 85% of Democrats think “the government should insure everyone” vs. 33% of Republican voters which calcifies inaction in a divided Congress though. Opposition to the Affordable Care Act (2010) has softened and Medicaid expansion has passed in 40 Blue and Red states.

In the 2024 election cycle, remedies for increased access and more affordability will pit Republicans calling for more competition, consumerism and transparency and Democrats calling for more government funding, regulation and fairness.

But more important, voter and employer frustration with partisan bickering sans solutions will set the stage for the vigorous debate about a single payer system in 2026 and after,

State elections will give more attention to healthcare issues than the Presidential race: That’s because Governors and state legislators set direction on issues like abortion rights, drug price controls, Medicaid funding, scope of practice allowances and others.

Increasingly, state Attorney’s General and Treasurers are weighing in on consolidation and spending. States referee workforce issues like nurse staffing requirements and others. And ballot referenda on healthcare issues trail only public education as a focus of grassroots voter activity. At the top of that list is abortion rights:

In 25 states and DC, there are no restrictions on access; in 14 states, abortion is banned and in 11 abortions—both procedures and medication—are legal, but with gestational limits from 6 weeks (GA), to between 12 and 22 weeks (AZ, UT, NE, KS, IA, IN, OH, NC, SC, FL). It’s an issue that divides legislators and increasingly delineates Blue and Red states and in many states remains unsettled.

Other healthcare issues, like ageism, will surface in Campaign 2024 in the context of other topics: Finally, healthcare will factor into other issues: Example: The leading Presidential candidates are seniors: President Biden was the oldest person to assume the office at age 78 and would be would be 86 at the end of his second term. Former President Trump was 70 when elected in 2016 and would be 81 if elected when his second term ends.

The majority of Americans are concerned about the impact of age on fitness to serve among aspirants for high office: cognitive impairment, dementia, physical limitations et al. will be necessary talking points in campaigns and media coverage. Similarly, cybersecurity looms as a focus where healthcare’s data-rich dependence is directly impacted. Growing concern about climate and the food supply, sourcing of raw good and materials from China used in drug manufacturing and many other headlines will infer healthcare context.

Summary:

Healthcare will be on the ballot in 2024 and might very well make the difference in who wins and loses in many state and local elections.

It will make a difference in the Presidential campaign as part of the economy and a major focus of government spending. Beyond abortion, the lack of attention to other aspects of the health system in the Milwaukee debate last week should in no way be interpreted as a pass for healthcare insiders.

Voters are restless and healthcare is contributing. Healthcare is far from ‘out of sight, out of mind’ in Campaign 2024.