At first, people delayed medical care for fear of catching Covid. But as the pandemic caused staggering unemployment, medical care has become unaffordable for many.

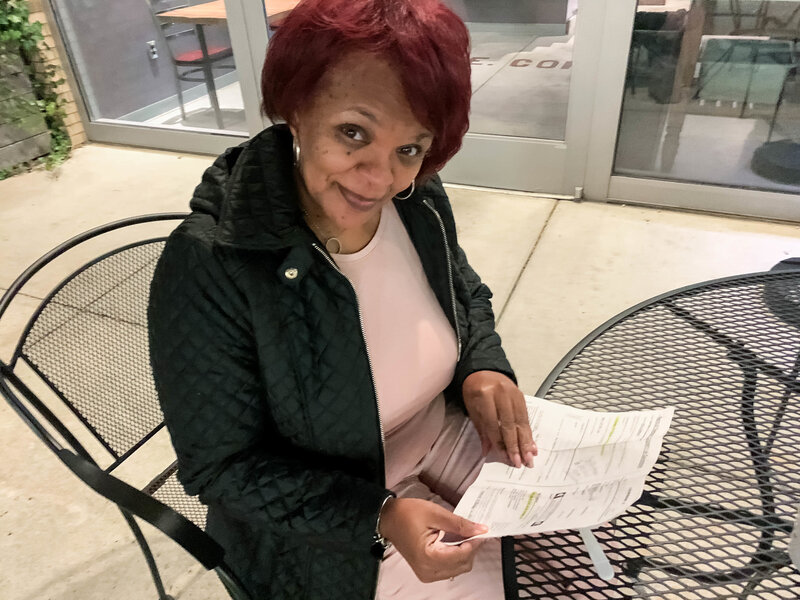

At first, Kristina Hartman put off getting medical care out of concern about the coronavirus. But then she lost her job as an administrator at a truck manufacturer in McKinney, Texas.

While she still has health insurance, she worries about whether she will have coverage beyond July, when her unemployment is expected to run out.

“It started out as a total fear of going to the doctor,” she said.

“I definitely am avoiding appointments.”

Ms. Hartman, who is 58, skipped a regular visit with her kidney doctor, and has delayed going to the endocrinologist to follow up on some abnormal lab results.

While hospitals and doctors across the country say many patients are still shunning their services out of fear of contagion — especially with new cases spiking — Americans who lost their jobs or have a significant drop in income during the pandemic are now citing costs as the overriding reason they do not seek the health care they need.

“We are seeing the financial pressure hit,” said Dr. Bijoy Telivala, a cancer specialist in Jacksonville, Fla. “This is a real worry,” he added, explaining that people are weighing putting food on the table against their need for care. “You don’t want a 5-year-old going hungry.”

Among those delaying care, he said, was a patient with metastatic cancer who was laid off while undergoing chemotherapy. He plans to stop treatments while he sorts out what to do when his health insurance coverage ends in a month.

The twin risks in this crisis — potential infection and the cost of medical care — have become daunting realities for the millions of workers who were furloughed, laid off or caught in the economic downturn. It echoes the scenarios that played out after the 2008 recession, when millions of Americans were unemployed and unable to afford even routine visits to the doctor for themselves or their children.

Almon Castor’s hours were cut at the steel distribution warehouse in Houston where he works about a month ago. Worried that a dentist might not take all the precautions necessary, he had been avoiding a root canal.

But the expense has become more pressing. He also works as a musician. “It’s not feasible to be able to pay for procedures with the lack of hours,” he said.

Nearly half of all Americans say they or someone they live with has delayed care since the onslaught of coronavirus, according to a survey last month from the Kaiser Family Foundation. While most of those individuals expected to receive care within the next three months, about a third said they planned to wait longer or not seek it at all.

While the survey didn’t ask people why they were putting off care, there is ample evidence that medical bills can be a powerful deterrent. “We know historically we have always seen large shares of people who have put off care for cost reasons,” said Liz Hamel, the director of public opinion and survey research at Kaiser.

And, just as the Great Recession led people to seek less hospital care, the current downturn is likely to have a significant impact, said Sara Collins, an executive at the Commonwealth Fund, who studies access to care. “This is a major economic recession,” she said. “It’s going to have an effect on people’s demand for health care.”

The inability to afford care is “going to be a bigger and bigger issue moving forward,” said Chas Roades, the co-founder of Gist Healthcare, which advises hospitals and doctors. Hospital executives say their patient volumes will remain at about 20 percent lower than before the pandemic.

“It’s going to be a jerky start back,” said Dr. Gary LeRoy, a physician in Dayton, Ohio, who is the president of the American Academy of Family Physicians. While some of his patients have returned, others are staying away.

But the consequences of these delays can be troubling. In a recent analysis of the sharp decline in emergency room visits during the pandemic, officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said there were worrisome signs that people who had heart attacks waited until their conditions worsened before going to the hospital.

Without income, many people feel they have no choice. Thomas Chapman stopped getting paid in March and ultimately lost his job as a director of sales. Even though he has high blood pressure and diabetes, Mr. Chapman, 64, didn’t refill any prescriptions for two months. “I stopped taking everything when I just couldn’t pay anymore,” he said.

After his legs began to swell, and he felt “very, very lethargic,” he contacted his doctor at Catalyst Health Network, a Texas group of primary care doctors, to ask about less expensive alternatives. A pharmacist helped, but Mr. Chapman no longer has insurance, and is not sure what he will do until he is eligible for Medicare later this year.

“We’re all having those conversations on a daily basis,” said Dr. Christopher Crow, the president of Catalyst, who said it was particularly tough in states, like Texas, that did not expand Medicaid. While some of those who are unemployed qualify for coverage under the Affordable Care Act, they may fall in the coverage gap where they do not receive subsidies to help them afford coverage.

Even those who are not concerned about losing their insurance are fearful of large medical bills, given how aggressively hospitals and doctors pursue people through debt collections, said Elisabeth Benjamin, a vice president at Community Service Society of New York, which works with people to get care.

“Americans are really very aware that their health care coverage is not as comprehensive as it should be, and it’s gotten worse over the past decade,” Ms. Benjamin said. After the last recession, they learned to forgo care rather than incur bills they can’t pay.

Geralyn Cerveny, who runs a day care in Kansas City, Mo., said she had Covid-19 in early April and is recovering. But her income has dropped as some families withdrew their children. Although her daughter is urging her to get some follow-up testing because she has some lingering symptoms from the virus, she is holding off because she does not want to end up with more medical bills if her health plan will not cover all of the care she needs. She said she would dread “a fight with the insurance company if you don’t meet their guidelines.”

Others are weighing what illness or condition merits the expense of a doctor or tests and other services. Eli Fels, a swim instructor and personal trainer who is pregnant, has been careful to stay up-to-date with her prenatal appointments in Cambridge, Mass. She and her doctor have relied on telemedicine appointments to reduce the risk of infection.

But Ms. Fels, who also lost her jobs but remains insured, has chosen not to receive care for her injured wrist in spite of concern over lasting damage. “I’ve put off medical care that doesn’t involve the baby,” she said, noting that her out-of-pocket cost for an M.R.I. to find out what was wrong “is not insubstantial.”

At Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, doctors have already seen the impact of delaying care. During the height of the pandemic, people who had heart attacks and serious fractures avoided the emergency room. “It was as if they disappeared, but they didn’t disappear,” said Dr. Jack Choueka, the chair of orthopedics. “People were dying in home; they just weren’t coming into the hospital.”

In recent weeks, people have begun to return, but with conditions worsened because of the time they had avoided care. A baby with a club foot will now need a more complicated treatment because it was not addressed immediately after birth.

Another child who did not have imaging promptly was found to have a tumor. “That tumor may have been growing for months unchecked,” Dr. Choueka said.