Category Archives: Out of Pocket Expenses

Unpacking one aspect of healthcare affordability

https://www.kaufmanhall.com/insights/blog/gist-weekly-april-12-2024

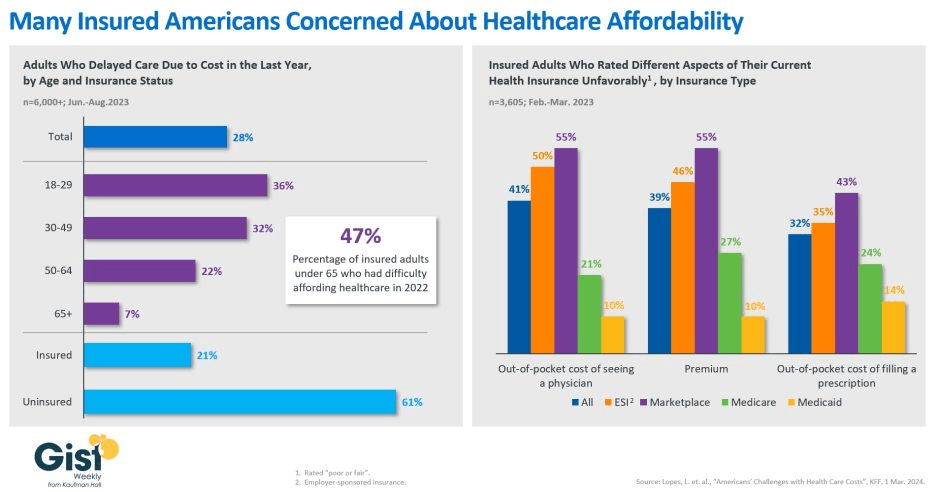

In this week’s graphic, we showcase recent KFF survey data on how healthcare costs impact the public, particularly those with health insurance.

Nearly half of US adults say it is difficult to afford healthcare, and in the last year, 28 percent have skipped or postponed care due to cost, with an even greater share of younger people delaying care due to cost concerns.

Although healthcare affordability has long been a problem for the uninsured, one in five adults with insurance skipped care in the past year because of cost. Insured Americans report low satisfaction with the affordability of their coverage.

In addition to high premiums, out-of-pocket costs to see a physician or fill a prescription are particular sources of concern. Adults with employer-sponsored or marketplace plans are far more likely to be dissatisfied with the affordability of their coverage, compared to those with government-sponsored plans.

With eight in ten American voters saying that it is “very important” for the 2024 presidential candidates to focus on the affordability of healthcare, we’ll no doubt see more attention focused on this issue as the presidential election race heats up.

The Heritage Foundation’s Medicare and Social Security Blueprint

If Congress in the next year or two succeeds in transforming Medicare into something that looks like a run-of-the mill Medicare Advantage plan for everyone – not just for those who now have the plans – it will mark the culmination of a 30-year project funded by the Heritage Foundation.

A conservative think tank, the Heritage Foundation grew to prominence in the 1970s and ’80s with a well-funded mission to remake or eliminate progressive governmental programs Americans had come to rely on, like Medicare, Social Security and Workers’ Compensation.

Some 30 million people already have been lured into private Medicare Advantage plans, eager to grab such sales enticements as groceries, gym memberships and a sprinkling of dental coverage while apparently oblivious to the restrictions on care they may encounter when they get seriously ill and need expensive treatment. That’s the time when you really need good insurance to pay the bills.

Congress may soon pass legislation that authorizes a study commission pushed by Heritage and some Republican members aimed at placing recommendations on the legislative table that would end Medicare and Social Security, replacing those programs with new ones offering lesser benefits for fewer people.

In other words, they would no longer be available to everyone in a particular group. Instead they would morph into something like welfare, where only the neediest could receive benefits.

How did these popular programs, now affecting 67.4 million Americans on Social Security and nearly 67 million on Medicare, become imperiled?

As I wrote in my book, Slanting the Story: The Forces That Shape the News, Heritage had embarked on a campaign to turn Medicare into a totally privatized arrangement. It’s instructive to look at the 30-year campaign by right-wing think tanks, particularly the Heritage Foundation, to turn these programs into something more akin to health insurance sold by profit-making companies like Aetna and UnitedHealthcare than social insurance, where everyone who pays into the system is entitled to a benefit when they become eligible.

The proverbial handwriting was on the wall as early as 1997 when a group of American and Japanese health journalists gathered at an apartment in Manhattan to hear a program about services for the elderly. The featured speaker was Dr. Robyn Stone who had just left her position as assistant secretary for the Department of Health and Human Services in the Clinton administration.

Stone chastised the American reporters in the audience, telling them: “What is amazing to me is that you have not picked up on probably the most significant story in aging since the 1960s, and that is passage of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, which creates Medicare Plus Choice” – a forerunner of today’s Advantage plans.

“This is the beginning of the end of entitlements for the Medicare program,” Stone said, explaining that the changes signaled a move toward a “defined contribution” program rather than a “defined benefit” plan with a predetermined set of benefits for everyone. “The legislation was so gently passed that nobody looked at the details.”

Robert Rosenblatt, who covered the aging beat for the Los Angeles Times, immediately challenged her. “It’s not the beginning of the end of Medicare as we know it,” he shot back. “It expands consumer choice.”

Consumer choice had become the watchword of the so-called “consumer movement,” ostensibly empowering shoppers – but without always identifying the conditions under which their choices must be made.

When consumers lured by TV pitchmen sign up for Medicare Advantage, how many of the sellers disclose that once those consumers leave traditional Medicare for an Advantage plan, they may be trapped. In most states, they will not be able to buy a Medicare supplement policy if they don’t like their new plan unless they are in super-good health.

In other words, most seniors are stuck. That can leave beneficiaries medically stranded when they have a serious, costly illness at a time in life when many are using up or have already exhausted their resources. I once asked a Medicare counselor what beneficiaries with little income would do if they became seriously ill and their Advantage plan refused to pay many of the bills, an increasingly common predicament. The cavalier answer I got was: “They could just go on Medicaid.”

The push to privatize Medicare began in February 1995 when Heritage issued a six-page committee brief titled “A Special Report to the House Ways and Means Committee”, which was sent to members of Congress, editorial writers, columnists, talk show hosts and other media. Heritage then spent months promoting its slant on the story. Along with other right-wing groups dedicated to transforming Medicare from social insurance to a private arrangement like car insurance, Heritage clobbered reporters who produced stories that didn’t fit the conservative narrative.

The right-wing Media Research Center singled out journalists who didn’t use the prescribed vocabulary to describe Heritage plans. Its newsletter criticized CBS reporter Linda Douglas when she reported that the senior citizens lobby had warned that the Republican budget would gut Medicare. The group reprimanded another CBS reporter, Connie Chung, for reporting that the House and Senate GOP plans “call for deep cuts in Medicare and other programs.” Haley Barbour, then Republican National Committee chairman, vowed to raise “unshirted hell” with the news media whenever they used the word “cut.” He wined and dined reporters, “educating” them on the “difference” between cuts and slowing Medicare’s growth. Former Republican U.S. Rep. John Kasich of Ohio, who chaired the House budget committee, called reporters warning them not to use the word “cut,” later admitting he “worked them over.”

As I wrote at the time, by fall of that year reporters had fallen in line. Douglas, who had been criticized all summer, got the words right and reported that the Republican bill contained a number of provisions “all adding up to a savings of $270 billion in the growth of Medicare spending.”

Fast forward to now. The Heritage Foundation’s Budget Blueprint for fiscal year 2023 offered ominous recommendations for Medicare, some of which might be enacted in a Republican administration. The think tank yet again called for a “premium support system” for Medicare, claiming that if its implementation was assumed in 2025, it “would reduce outlays by $1 trillion during the FY 2023-2032 period.” Heritage argues that the controversial approach would foster “intense competition among health plans and providers,” “expand beneficiaries’ choices,” “control costs,” “slow the growth of Medicare spending,” and “stimulate innovation.”

The potential beneficiaries would be given a sum of money, often called a premium support, to shop in the new marketplace, which could resemble today’s sales bazaar for Medicare Advantage plans, setting up the possibility for more hype and more sellers hoping to cash in on the revamped Medicare program. Many experts fear that such a program ultimately could destroy what is left of traditional Medicare, which about half of the Medicare population still prefers.

In other words, most seniors are stuck.

That can leave beneficiaries medically stranded when they have a serious, costly illness at a time in life when many are using up or have already exhausted their resources. I once asked a Medicare counselor what beneficiaries with little income would do if they became seriously ill and their Advantage plan refused to pay many of the bills, an increasingly common predicament. The cavalier answer I got was: “They could just go on Medicaid.”

The push to privatize Medicare began in February 1995 when Heritage issued a six-page committee brief titled “A Special Report to the House Ways and Means Committee”, which was sent to members of Congress, editorial writers, columnists, talk show hosts and other media. Heritage then spent months promoting its slant on the story. Along with other right-wing groups dedicated to transforming Medicare from social insurance to a private arrangement like car insurance, Heritage clobbered reporters who produced stories that didn’t fit the conservative narrative.

The right-wing Media Research Center singled out journalists who didn’t use the prescribed vocabulary to describe Heritage plans. Its newsletter criticized CBS reporter Linda Douglas when she reported that the senior citizens lobby had warned that the Republican budget would gut Medicare. The group reprimanded another CBS reporter, Connie Chung, for reporting that the House and Senate GOP plans “call for deep cuts in Medicare and other programs.” Haley Barbour, then Republican National Committee chairman, vowed to raise “unshirted hell” with the news media whenever they used the word “cut.” He wined and dined reporters, “educating” them on the “difference” between cuts and slowing Medicare’s growth. Former Republican U.S. Rep. John Kasich of Ohio, who chaired the House budget committee, called reporters warning them not to use the word “cut,” later admitting he “worked them over.”

As I wrote at the time, by fall of that year reporters had fallen in line. Douglas, who had been criticized all summer, got the words right and reported that the Republican bill contained a number of provisions “all adding up to a savings of $270 billion in the growth of Medicare spending.”

Fast forward to now. The Heritage Foundation’s Budget Blueprint for fiscal year 2023 offered ominous recommendations for Medicare, some of which might be enacted in a Republican administration. The think tank yet again called for a “premium support system” for Medicare, claiming that if its implementation was assumed in 2025, it “would reduce outlays by $1 trillion during the FY 2023-2032 period.” Heritage argues that the controversial approach would foster “intense competition among health plans and providers,” “expand beneficiaries’ choices,” “control costs,” “slow the growth of Medicare spending,” and “stimulate innovation.”

The potential beneficiaries would be given a sum of money, often called a premium support, to shop in the new marketplace, which could resemble today’s sales bazaar for Medicare Advantage plans, setting up the possibility for more hype and more sellers hoping to cash in on the revamped Medicare program. Many experts fear that such a program ultimately could destroy what is left of traditional Medicare, which about half of the Medicare population still prefers.

In a Republican administration with a GOP Congress, some of the recommendations, or parts of them, might well become law. The last 30 years have shown that the Heritage Foundation and other organizations driven by ideological or financial reasons want to transform Medicare, and they are committed for the long haul. They have the resources to promote their cause year after year, resulting in the continual erosion of traditional Medicare by Advantage Plans, many of which are of questionable value when serious illness strikes.

The seeds of Medicare’s destruction are in the air.

The program as it was set out in 1965 has kept millions of older Americans out of medical poverty for over 50 years, but it may well become something else – a privatized health care system for the oldest citizens whose medical care will depend on the profit goals of a handful of private insurers. It’s a future that STAT’s Bob Herman, whose reporting has explored the inevitable clash between health care and an insurer’s profit goals, has shown us.

In the long term, the gym memberships, the groceries, the bit of dental and vision care so alluring today may well disappear, and millions of seniors will be left once again to the vagaries of America’s private insurance marketplace.

Healthcare Spending 2000-2022: Key Trends, Five Important Questions

Last week, Congress avoided a partial federal shutdown by passing a stop-gap spending bill and now faces March 8 and March 22 deadlines for authorizations including key healthcare programs.

This week, lawmakers’ political antenna will be directed at Super Tuesday GOP Presidential Primary results which prognosticators predict sets the stage for the Biden-Trump re-match in November. And President Biden will deliver his 3rd State of the Union Address Thursday in which he is certain to tout the economy’s post-pandemic strength and recovery.

The common denominator of these activities in Congress is their short-term focus: a longer-term view about the direction of the country, its priorities and its funding is not on its radar anytime soon.

The healthcare system, which is nation’s biggest employer and 17.3% of its GDP, suffers from neglect as a result of chronic near-sightedness by its elected officials. A retrospective about its funding should prompt Congress to prepare otherwise.

U.S. Healthcare Spending 2000-2022

Year-over-year changes in U.S. healthcare spending reflect shifting demand for services and their underlying costs, changes in the healthiness of the population and the regulatory framework in which the U.S. health system operates to receive payments. Fluctuations are apparent year-to-year, but a multiyear retrospective on health spending is necessary to a longer-term view of its future.

The period from 2000 to 2022 (the last year for which U.S. spending data is available) spans two economic downturns (2008–2010 and 2020–2021); four presidencies; shifts in the composition of Congress, the Supreme Court, state legislatures and governors’ offices; and the passage of two major healthcare laws (the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 and the Affordable Care Act of 2010).

During this span of time, there were notable changes in healthcare spending:

- In 2000, national health expenditures were $1.4 trillion (13.3% of gross domestic product); in 2022, they were $4.5 trillion (17.3% of the GDP)—a 4.1% increase overall, a 321% increase in nominal spending and a 30% increase in the relative percentage of the nation’s GDP devoted to healthcare. No other sector in the economy has increased as much.

- In the same period, the population increased 17% from 282 million to 333 million, per capita healthcare spending increased 178% from $4,845 to $13,493 due primarily to inflation-impacted higher unit costs for , facilities, technologies and specialty provider costs and increased utilization by consumers due to escalating chronic diseases.

- There were notable changes where dollars were spent: Hospitals remained relatively unchanged (from $415 billion/30.4% of total spending to $1.355 trillion/31.4%), physician services shrank (from $288.2 billion/21.1% to $884.8/19.6%) and prescription drugs were unchanged (from $122.3 billion/8.95% to $405.9 billion/9.0%).

- And significant changes in funding Out-of-pocket shrank from 14.2% ($193.6 billion in 2020) to (10.5% ($471 billion) in 2020, private insurance shrank from $441 billion/32.3% to $1.289 trillion/29%, Medicare spending grew from $224.8 billion/16.5% to $944.3billion/21%; Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program spending grew from $203.4 billion/14.9% to $7805.7billion/18%; and Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare spending grew from $19.1 billion/1.4% to $98 billion/2.2%.

Looking ahead (2022-2031), CMS forecasts average National Health Expenditures (NHE) will grow at 5.4% per year outpacing average GDP growth (4.6%) and resulting in an increase in the health spending share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 17.3% in 2021 to 19.6% in 2031.

The agency’s actuaries assume

“The insured share of the population is projected to reach a historic high of 92.3% in 2022… Medicaid enrollment will decline from its 2022 peak of 90.4M to 81.1M by 2025 as states disenroll beneficiaries no longer eligible for coverage. By 2031, the insured share of the population is projected to be 90.5 percent. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is projected to result in lower out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs for 2024 and beyond as Medicare beneficiaries incur savings associated with several provisions from the legislation including the $2,000 annual out-of-pocket spending cap and lower gross prices resulting from negotiations with manufacturers.”

My take:

The reality is this: no one knows for sure what the U.S. health economy will be in 2025 much less 2035 and beyond. There are too many moving parts, too much invested capital seeking near-term profits, too many compensation packages tied to near-term profits, too many unknowns like the impact of artificial intelligence and court decisions about consolidation and too much political risk for state and federal politicians to change anything.

One trend stands out in the data from 2000-2022: The healthcare economy is increasingly dependent on indirect funding by taxpayers and less dependent on direct payments by users.

In the last 22 years, local, state and federal government programs like Medicare, Medicaid and others have become the major sources of funding to the system while direct payments by consumers and employers, vis-à-vis premium out-of-pocket costs, increased nominally but not at the same rate as government programs. And total spending has increased more than the overall economy (GDP), household wages and costs of living almost every year.

Thus, given the trends, five questions must be addressed in the context of the system’s long-term solvency and effectiveness looking to 2031 and beyond:

- Should its total spending and public funding be capped?

- Should the allocation of funds be better adapted to innovations in technology and clinical evidence?

- Should the financing and delivery of health services be integrated to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of the system?

- Should its structure be a dual public-private system akin to public-private designations in education?

- Should consumers play a more direct role in its oversight and funding?

Answers will not be forthcoming in Campaign 2024 despite the growing significance of healthcare in the minds of voters. But they require attention now despite political neglect.

PS: The month of February might be remembered as the month two stalwarts in the industry faced troubles:

United HealthGroup, the biggest health insurer, saw fallout from a cyberattack against its recently acquired (2/22) insurance transaction processor by ALPHV/Blackcat, creating havoc for the 6000 hospitals, 1 million physicians, and 39,000 pharmacies seeking payments and/or authorizations. Then, news circulated about the DOJ’s investigation about its anti-competitive behavior with respect to the 90,000 physicians it employs. Its stock price ended the week at 489.53, down from 507.14 February 1.

And HCA, the biggest hospital operator, faced continued fallout from lawsuits for its handling of Mission Health (Asheville) where last Tuesday, a North Carolina federal court refused to dismiss a lawsuit accusing it of scheming to restrict competition and artificially drive-up costs for health plans. closed at 311.59 last week, down from 314.66 February 1.

What a Biden-Trump Re-Match means for Healthcare Politics: How the Campaigns will Position their Differences to Voters

With the South Carolina Republican primary results in over the weekend, it seems a Biden-Trump re-match is inevitable. Given the legacies associated with Presidencies of the two and the healthcare platforms espoused by their political parties, the landscape for healthcare politics seems clear:

| Healthcare Issue | Biden Policy | Trump Policy |

| Access to Abortion | ‘It’s a basic right for women protected by the Federal Government’ | ‘It’s up to the states and should be safe and rare. A 16-week ban should be the national standard.’ |

| Ageism | ‘President Biden is alert and capable. It’s a non-issue.’ | ‘President Biden is senile and unlikely to finish a second term is elected. President Trump is active and prepared.’ |

| Access to IVF Treatments | ‘It’s a basic right and should be universally accessible in every state and protected’ | ‘It’s a complex issue that should be considered in every state.’ |

| Affordability | ‘The system is unaffordable because it’s dominated by profit-focused corporations. It needs increased regulation including price controls.’ | ‘The system is unaffordable to some because it’s overly regulated and lacks competition and price transparency.’ |

| Access to Health Insurance Coverage | ‘It’s necessary for access to needed services & should be universally accessible and affordable.’ | ‘It’s a personal choice. Government should play a limited role.’ |

| Public health | ‘Underfunded and increasingly important.’ | ‘Fragmented and suboptimal. States should take the lead.’ |

| Drug prices | ‘Drug companies take advantage of the system to keep prices high. Price controls are necessary to lower costs.’ | ‘Drug prices are too high. Allowing importation and increased price transparency are keys to reducing costs.’ |

| Medicare | ‘It’s foundational to seniors’ wellbeing & should be protected. But demand is growing requiring modernization (aka the value agenda) and additional revenues (taxes + appropriations).’ | ‘It’s foundational to senior health & in need of modernization thru privatization. Waste and fraud are problematic to its future.’ |

| Medicaid | ‘Medicaid Managed Care is its future with increased enrollment and standardization of eligibility & benefits across states.’ | ‘Medicaid is a state program allowing modernization & innovation. The federal role should be subordinate to the states.’ |

| Competition | ‘The federal government (FTC, DOJ) should enhance protections against vertical and horizontal consolidation that reduce choices and increase prices in every sector of healthcare.’ | ‘Current anti-trust and consumer protections are adequate to address consolidation in healthcare.’ |

| Price Transparency | ‘Necessary and essential to protect consumers. Needs expansion.’ | ‘Necessary to drive competition in markets. Needs more attention.’ |

| The Affordable Care Act | ‘A necessary foundation for health system modernization that appropriately balances public and private responsibilities. Fix and Repair’ | ‘An unnecessary government takeover of the health system that’s harmful and wasteful. Repeal and Replace.’ |

| Role of federal government | ‘The federal government should enable equitable access and affordability. The private sector is focused more on profit than the public good.’ | ‘Market forces will drive better value. States should play a bigger role’ |

My take:

Polls indicate Campaign 2024 will be decided based on economic conditions in the fall 2024 as voters zero in on their choice. Per KFF’s latest poll, 74% of adults say an unexpected healthcare bill is their number-one financial concern—above their fears about food, energy and housing. So, if you’re handicapping healthcare in Campaign 2024, bet on its emergence as an economic issue, especially in the swing states (Michigan, Florida, North Carolina, Georgia and Arizona) where there are sharp health policy differences and the healthcare systems in these states are dominated by consolidated hospitals and national insurers.

- Three issues will be the primary focus of both campaigns: women’s health and access to abortion, affordability and competition. On women’s health, there are sharp differences; on affordability and competition, the distinctions between the campaigns will be less clear to voters. Both will opine support for policy changes without offering details on what, when and how.

- The Affordable Care Act will surface in rhetoric contrasting a ‘government run system’ to a ‘market driven system.’ In reality, both campaigns will favor changes to the ACA rather than repeal.

- Both campaigns will voice support for state leadership in resolving abortion, drug pricing and consolidation. State cost containment laws and actions taken by state attorneys general to limit hospital consolidation and private equity ownership will get support from both campaigns.

- Neither campaign will propose transformative policy changes: they’re too risky. integrating health & social services, capping total spending, reforms of drug patient laws, restricting tax exemptions for ‘not for profit’ hospitals, federalizing Medicaid, and others will not be on the table. There’s safety in promoting populist themes (price transparency, competition) and steering away from anything more.

As the primary season wears on (in Michigan tomorrow and 23 others on/before March 5), how the health system is positioned in the court of public opinion will come into focus.

Abortion rights will garner votes; affordability, price transparency, Medicare solvency and system consolidation will emerge as wedge issues alongside.

PS: Re: federal budgeting for key healthcare agencies, two deadlines are eminent: March 1 for funding for the FDA and the VA and March 8 for HHS funding.

Cartoon – Physician-Assisted Bankruptcy

How GoFundMe use demonstrates the problem of healthcare affordability

https://mailchi.mp/1e28b32fc32e/gist-weekly-february-9-2024?e=d1e747d2d8

Published this week in The Atlantic, this piece chronicles the increase in Americans using crowdfunding sites like GoFundMe to cover—or at least attempt to cover—their catastrophic medical expenses. Envisioned as a tool to fund “ideas and dreams,” the GoFundMe platform saw a 25-fold increase in the number of campaigns dedicated to medical care from 2011 to 2020.

Medical campaigns have garnered at least one third of all donations and raised $650M in contributions.

The article’s accounts of life-saving care leading to bankrupting medical bills are heartbreaking and familiar, and despite some success stories, the average GoFundMe medical campaign falls well short of its target donation goal.

The Gist:

Although unfortunately not surprising, these crowdfunding stats reflect our nation’s healthcare affordability crisis.

Online campaigns can alleviate real financial burdens for some people; however, they come at the costs of publicly exposing personal medical information, potentially offering false hope, and financially imposing on friends and family.

The majority of personal bankruptcies are caused by medical expenses, and recent changes like removing some levels of medical debt from credit reports are only a small step toward reducing the personal financial effects of medical debt.

Absent larger-scale healthcare payment and coverage reform, healthcare industry leaders continue to be challenged with finding ways to decouple the provision of essential medical care from the risk of financial ruin for patients.

ACA enrollment continues at a record pace

https://nxslink.thehill.com/view/6230d94bc22ca34bdd8447c8k3p6r.11v6/ce256994

Affordable Care Act (ACA) enrollment appears poised to reach record levels once again as signups grew by more than a third of what they were this time last year, a fact the White House is using to continue to draw attention to former President Trump’s threats to try again to repeal the law.

More than 15 million people have signed up for plans in states that use HealthCare.gov, representing a 33 percent increase from last year. The Biden administration estimates 19 million will sign up for plans by the Jan. 16 deadline.

On Dec. 15, the deadline for coverage starting Jan. 1, more than 745,000 people selected a plan through HealthCare.gov — the most in a day in history, the Department of Health and Human Services said.

For 2023 plans, more than 16.3 million people signed up through HealthCare.gov last year, another record. Of those who enrolled for this year, 22 percent were new to the marketplace.

This year’s enrollment had some unusual factors that may have played a part in boosting enrollment. Those who were disenrolled from Medicaid this year during the “unwinding” period were allowed to sign up for ACA plans earlier than normal.

There was also stronger insurer participation in the program this year, providing significantly more options for customers to choose from.

“Thanks to policies I signed into law, millions of Americans are saving hundreds or thousands of dollars on health insurance premiums,” President Biden said on Wednesday.

“Extreme Republicans want to stop these efforts in their tracks,” he added. “At every turn, extreme Republicans continue to side with special interests to keep prescription drug prices high and to deny millions of people health coverage.”

The US doesn’t have universal health care — but these states (almost) do

https://www.vox.com/policy/23972827/us-aca-enrollment-universal-health-insurance

Ten states have uninsured rates below 5 percent. What are they doing right?

Universal health care remains an unrealized dream for the United States. But in some parts of the country, the dream has drawn closer to a reality in the 13 years since the Affordable Care Act passed.

Overall, the number of uninsured Americans has fallen from 46.5 million in 2010, the year President Barack Obama signed his signature health care law, to about 26 million today. The US health system still has plenty of flaws — beyond the 8 percent of the population who are uninsured, far higher than in peer countries, many of the people who technically have health insurance still find it difficult to cover their share of their medical bills. Nevertheless, more people enjoy some financial protection against health care expenses than in any previous period in US history.

The country is inching toward universal coverage. If everybody who qualified for either the ACA’s financial assistance or its Medicaid expansion were successfully enrolled in the program, we would get closer still: More than half of the uninsured are technically eligible for government health care aid.

Particularly in the last few years, it has been the states, using the tools made available by them by the ACA, that have been chipping away most aggressively at the number of uninsured.

Today, 10 states have an uninsured rate below 5 percent — not quite universal coverage, but getting close. Other states may be hovering around the national average, but that still represents a dramatic improvement from the pre-ACA reality: In New Mexico, for instance, 23 percent of its population was uninsured in 2010; now just 8 percent is.

Their success indicates that, even without another major federal health care reform effort, it is possible to reduce the number of uninsured in the United States. If states are more aggressive about using all of the tools available to them under the ACA, the country could continue to bring down the number of uninsured people within its borders.

The law gave states discretion to build upon its basic structure. Many received approval from the federal government to create programs that lower premiums; some also offer state subsidies in addition to the federal assistance to reduce the cost of coverage, including for people who are not eligible for federal aid, such as undocumented immigrants. A few states are even offering new state-run health plans that will compete with private offerings.

I asked several leading health care experts which states stood out to them as having fully weaponized the ACA to reduce the number of uninsured. There was not a single answer.

“I don’t think any state has taken advantage of everything,” said Larry Levitt, executive vice president at the KFF health policy think tank. “No state has put all the pieces together to the full extent available under the ACA.”

But a few stood out for the steps they have taken over the last decade to strive toward universal health care.

Massachusetts (and New Mexico): Streamlined enrollment and state subsidies

Massachusetts has the lowest uninsured rate of any state: Just 2.4 percent of the population lacks coverage. It had a head start: The law provided the model for the ACA itself, with its system of government subsidies for private plans sold on a public marketplace that existed prior to 2010.

But experts say it still deserves credit for the steps it has taken since the Massachusetts model was applied to the rest of the country. Matt Fiedler, a senior fellow with the Brookings Schaeffer Initiative on Health Policy, said two policies stood above any others in expanding coverage: integrating the enrollment process for both Medicaid and ACA marketplace plans and offering state-based assistance on top of the law’s federal subsidies.

Massachusetts was among the first states to do both.

“The former can do a lot to reduce the risk that people lose their coverage when incomes change,” Fiedler told me, “while the latter directly improves affordability and thereby promotes take-up.”

Integrated enrollment means that, for the consumer, they can be directed to either the ACA’s marketplace (where they can use government subsidies to buy private coverage) or to the state Medicaid program through one portal. They enter their information and the state tells them which program they should enroll in. Without that integration, people might have to first apply to Medicaid and then, if they don’t qualify, separately seek out marketplace coverage. The more steps that a person must take to successfully enroll in a health plan, the more likely it is people will fall through the cracks.

The state assistance, meanwhile, both reduces premiums for people and makes it easier for them to afford more generous coverage, with lower out-of-pocket costs when they actually use medical services. Nine states including Massachusetts now have state assistance, with interest picking up in the past few years.

New Mexico, for example, only recently converted to a state-based ACA marketplace and started offering additional aid in 2023. Having already seen some dramatic improvements, it remains to be seen how much more progress the state can make toward universal coverage with that policy in place.

Minnesota and New York: The Basic Health Plan states

The basic structure of the ACA was this: Medicaid expansion for people living in or near poverty and marketplace plans for people with incomes above that. But the law included an option for states to more seamlessly integrate those two populations — and so far, the two states that have taken advantage of it, Minnesota and New York, are also among those states with the lowest uninsured rates. Just 4.3 percent of Minnesotans and 4.9 percent of New Yorkers lack coverage today.

They have both created Basic Health Plans, the product of one of the more obscure provisions of the health care law. This is a state-regulated health insurance plan meant to cover people up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level (about $29,000 for an individual or $50,000 for a family of three). Those are people who may not technically qualify for Medicaid under the ACA but who can still struggle to afford their monthly premiums and out-of-pocket obligations with a marketplace plan.

In both states, the Basic Health Plans offered insurance options with lower premiums and reduced cost-sharing responsibilities than the marketplace coverage that they would otherwise have been left with. In New York, for example, people between 100 percent and 150 percent of the federal poverty level pay no premiums at all, while people between 150 percent and 200 percent pay just $20 per month.

There is good evidence that the approach has increased coverage: In New York, for example, enrollment among people below 200 percent of the poverty level increased by 42 percent when the state adopted its BHP in 2016, compared to what it had been the year before when those people were relegated to conventional marketplace coverage.

State interest in Basic Health Plans has been limited so far, but Minnesota and New York provide a model others could follow. Fiedler said part of the basic plans’ success in those states has been using Medicaid managed-care companies to administer the plan: Those insurers already pay providers lower rates than marketplace plans do and the savings give the states money to reduce premiums and cost-sharing.

Colorado and Washington: Public options and assistance for the undocumented

These states have been inventive in myriad ways. They are both early adopters of a public option, a government health plan that competes with private plans on the marketplace, a policy also being tested in Nevada.

There is another policy that unites them, one that addresses a sizable part of the remaining uninsured nationwide: They both provide some state subsidies to undocumented immigrants.

Most uninsured Americans are already technically eligible for some kind of government assistance, whether Medicaid or marketplace subsidies. But there is a large chunk of people who are not: About 29 percent of the US’s uninsured are ineligible for government aid, among them the people who are in the country undocumented. Those people bear the full cost of their medical bills and may avoid care for that reason (among others, of course).

Starting this year, Washington is allowing undocumented people with incomes that would make them eligible for Medicaid expansion to enroll in that program, and making state subsidies available to people with higher incomes no matter their immigration status. Colorado has set aside a small pool of money annually to provide state aid to about 11,000 undocumented people. (After that threshold is hit, those folks can still enroll in a health plan but they must pay the full price.)

Interest has been robust: Last year, Colorado hit the enrollment limit after about a month. This year, enrollment capped out in just two days, suggesting the state may need to put more money behind the effort.

It is difficult to imagine insurance subsidies for undocumented people nationwide any time soon, given the fraught national politics of immigration. But states are finding ways to make inroads on their own: California has made undocumented people eligible for Medicaid.

Through these and other means, they are helping the US inch toward universal health care.

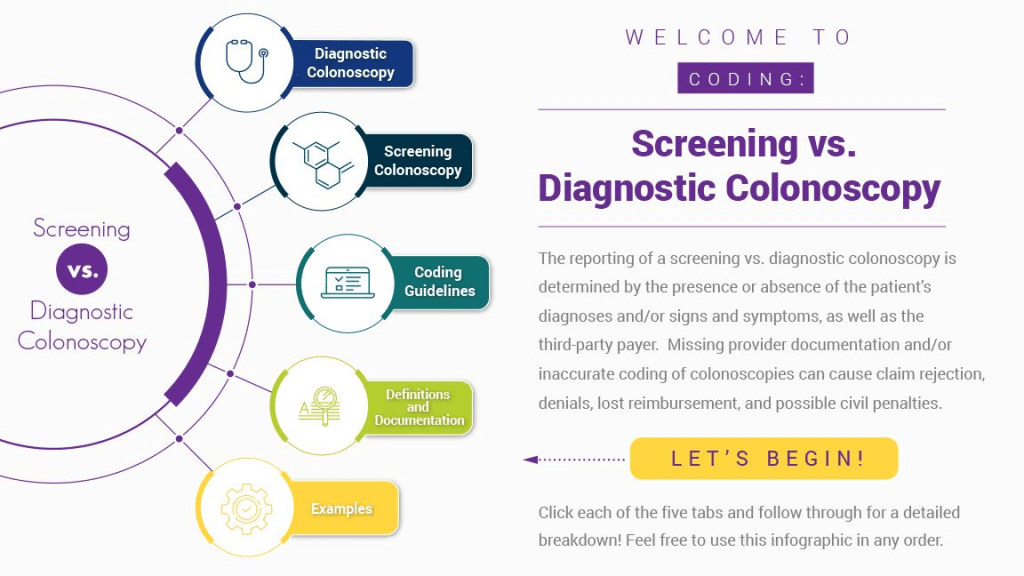

Higher-risk patients paying more for colonoscopies

https://mailchi.mp/9b1afd2b4afb/the-weekly-gist-december-1-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

Published this week in Stat, this article explores the confusing payment landscape patients must navigate when receiving colonoscopies. While the Affordable Care Act requires that preventative care services be covered without cost-sharing, this only applies to the “screening” colonoscopies that low-risk patients are recommended to get every ten years.

But when procedures are performed at more frequent intervals for higher-risk patients, they are called “surveillance” or “diagnostic” colonoscopies, for which patients have no guarantees of cost-sharing protections, despite being essentially the same procedure, done for the same purpose.

If a gastroenterologist finds and excises one or more precancerous polyps during a screening colonoscopy, the procedure can leave the patient—especially one with a high deductible health plan—with a large, unexpected bill.

The Gist: Against the backdrop of a sharp rise in colorectal cancer rates among US adults under 65, articles like this are a frustrating demonstration of how insurance incentive structures can work against optimal care delivery.

Incentives should be carefully designed such that proven, preventative screenings—at the discretion of their doctor—are widely available to patients with minimal financial barriers. Surely, no one is “choosing” to have an “unnecessary” colonoscopy—as the procedure is notoriously disliked by patients.