Despite a raft of data suggesting that wearing face masks (in conjunction with hand washing and social distancing) is effective in preventing person-to-person transmission of the coronavirus, the practice is still a partisan political issue in some places even as new cases continue to rise.

A new review published in The Lancet looked at 172 observational studies and found that masks are effective in many settings in preventing the spread of the coronavirus (though the results cannot be treated with absolute certainty since they were not obtained through randomized trials, the Washington Post notes).

Another recent study found that wearing a mask was the most effective way to reduce the transmission of the virus.

90% of Americans now say they’re wearing a mask in compliance with the CDC’s recommendations, up from 78% in April, according to a new poll conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago for the Data Foundation.

But despite the conclusive research and what seems to be a public consensus, masks remain a divisive subject.

As new coronavirus cases surge in Arizona, where cases have jumped 300% since the beginning of May, for instance, Governor Doug Ducey has not made it mandatory to wear masks in public, and in Orange County, California, officials on Friday rescinded a mask mandate after public backlash, even as cases rise; when cases peaked in April, on the other hand, New York made wearing a mask mandatory when people could not socially distance from others, and other states passed similar restrictions.

Part of the politicization of masks may have to do with resistance to heavy-handed government mandates, which in this case could cause people who are already skeptical of wearing face coverings to dig in their heels.

Lindsay Wiley, an American University Washington College of Law professor specializing in public health law and ethics, told NPR last month that stringent mask requirements “can actually cause people who are skeptical of wearing masks to double down.” And in turn, that “reinforce[s] what they perceive to be a positive association with refusing to wear a mask … that they love freedom, that they’re smart and skeptical of public health recommendations.”

Masks have also become a heavily politicized issue in recent weeks: Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) last month voiced his support of mask wearing in public, for instance, in contrast to President Trump and other GOP leaders who have portrayed masks as a sign of weakness. Trump infamously refused to wear a face mask as he toured a Ford facility in Michigan last month. When asked about the mask, he said that he wore one in private but “didn’t want to give the press the pleasure of seeing it.” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has voiced her support for the practice: “real men wear masks,” she said earlier this month.

A video posted to Twitter on Friday showed a street in New York City’s East Village that was packed with people ignoring social distancing guidelines, most of whom were not wearing masks, drew widespread criticism. “When there’s a new spike people will blame the (masked) protests, but it’s really gonna be maskless crap like this,” one Twitter user wrote.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo even weighed in on the scene. “Don’t make me come down there,” he tweeted.

Dr. Anthony Fauci told a British newspaper Sunday that something resembling normal life in the U.S. would likely return in “a year or so,” with the coronavirus pandemic expected to require social distancing and other mitigation efforts through the fall and winter, although political divisiveness, reopening efforts and the George Floyd protests could add more layers of difficulty to the country’s recovery.

“I would hope to get to some degree of real normality within a year or so. But I don’t think it’s this winter or fall,” Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told The Telegraph Sunday.

Fauci also told the newspaper that the travel ban from the U.K., the European Union, China and Brazil will likely stay in place for “months,” based on “what’s going on with the infection rate.”

Within the U.S., Florida, California and Texas hit all-time daily highs in reported Covid-19 cases, while the Centers for Disease Control predicted six states (Arizona, Arkansas, Hawaii, North Carolina, Utah and Vermont) will see higher death tolls over the next month.

U.S., where states that aren’t making them mandatory, like California, are seeing cases spike while New York, where the protective gear is required, has the country’s lowest spread rate.

“We’re seeing several states, as they try to reopen and get back to normal, starting to see early indications [that] infections are higher than previously,” Fauci said.

Over 2 million. That’s how many confirmed coronavirus cases are in the U.S., which leads the world both in the number of infections and casualties from the disease, according to data from Johns Hopkins University.

Despite Fauci’s immediate conservative outlook on when life can return to normal, he’s hopeful that multiple Covid-19 vaccines could be found by the end of 2020. “We have potential vaccines making significant progress. We have maybe four or five,” he told The Telegraph. Although “you can never guarantee success with a vaccine,” Fauci added, from “everything we have seen from early results, it’s conceivable we get two or three vaccines that are successful.”

The U.S. is not facing a second wave of coronavirus. “We really never quite finished the first wave,” according to Dr. Ashish Jha, a global health professor at Harvard. In an NPR interview, Jha said the first wave is unlikely to be finished “anytime soon.”

The World Health Organization designated the coronavirus outbreak as a pandemic on March 11, 2020. As of Sunday, the pandemic is approaching its fifth month, and few countries have had success in beating back their outbreaks. New Zealand has essentially returned to normal life after eliminating coronavirus, while countries like the U.S., the U.K. and Brazil, among others, continue to see new cases and report deaths.

Within the U.S., efforts to reduce cases and deaths, like mask wearing, have become partisan political issues. Desires both from elected officials and some citizens to reopen economies have also impacted the pandemic, as states that reopened earlier, like Florida, are seeing numbers of cases spike. Concerns that recent protests sparked by George Floyd’s killing will also further spread the coronavirus are present, but have not yet been proven, as symptoms can take up to 14 days to develop.

Public Health Officials Face Wave Of Threats, Pressure Amid Coronavirus Response

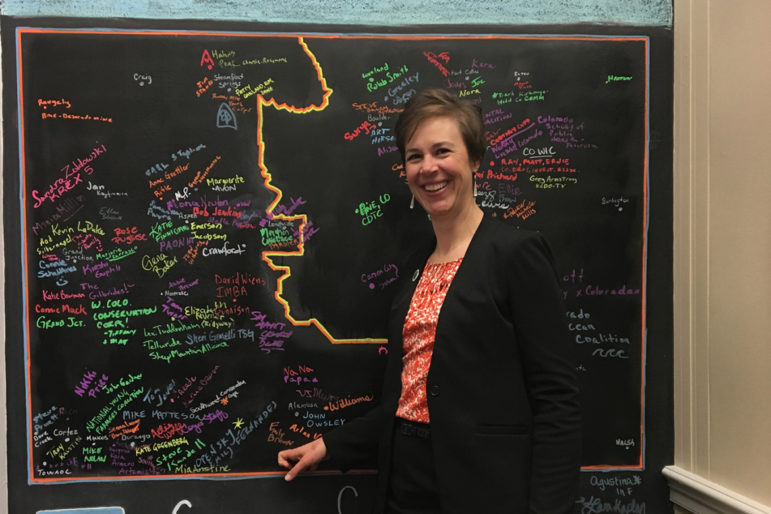

Emily Brown was director of the Rio Grande County Public Health Department in Colorado until May 22, when the county commissioners fired her after battling with her over coronavirus restrictions. “They finally were tired of me not going along the line they wanted me to go along,” she says.

Emily Brown was stretched thin.

As the director of the Rio Grande County Public Health Department in rural Colorado, she was working 12- and 14-hour days, struggling to respond to the pandemic with only five full-time employees for more than 11,000 residents. Case counts were rising.

She was already at odds with county commissioners, who were pushing to loosen public health restrictions in late May, against her advice. She had previously clashed with them over data releases and had haggled over a variance regarding reopening businesses.

But she reasoned that standing up for public health principles was worth it, even if she risked losing the job that allowed her to live close to her hometown and help her parents with their farm.

Then came the Facebook post: a photo of her and other health officials with comments about their weight and references to “armed citizens” and “bodies swinging from trees.”

The commissioners had asked her to meet with them the next day. She intended to ask them for more support. Instead, she was fired.

“They finally were tired of me not going along the line they wanted me to go along,” she said.

In the battle against COVID-19, public health workers spread across states, cities and small towns make up an invisible army on the front lines. But that army, which has suffered neglect for decades, is under assault when it’s needed most.

Officials who usually work behind the scenes managing everything from immunizations to water quality inspections have found themselves center stage. Elected officials and members of the public who are frustrated with the lockdowns and safety restrictions have at times turned public health workers into politicized punching bags, battering them with countless angry calls and even physical threats.

On Thursday, Ohio’s state health director, who had armed protesters come to her house, resigned. The health officer for Orange County, California, quit Monday after weeks of criticism and personal threats from residents and other public officials over an order requiring face coverings in public.

As the pressure and scrutiny rise, many more health officials have chosen to leave or been pushed out of their jobs. A review by KHN and The Associated Press finds at least 27 state and local health leaders have resigned, retired or been fired since April across 13 states.

In California, senior health officials from seven counties, including the Orange County officer, have resigned or retired since March 15. Dr. Charity Dean, the second in command at the state Department of Public Health, submitted her resignation June 4.

These officials have left their posts due to a mix of backlash and stressful, nonstop working conditions, all while dealing with chronic staffing and funding shortages.

Some health officials have not been up to the job during the biggest health crisis in a century. Others previously had plans to leave or cited their own health issues.

But Lori Tremmel Freeman, CEO of the National Association of County and City Health Officials, said the majority of what she calls an “alarming” exodus resulted from increasing pressure as states reopen. Three of those 27 were members of her board and well known in the public health community — Rio Grande County’s Brown; Detroit’s senior public health adviser, Dr. Kanzoni Asabigi; and the head of North Carolina’s Gaston County Department of Health and Human Services, Chris Dobbins.

Asabigi’s sudden retirement, considering his stature in the public health community, shocked Freeman. She also was upset to hear about the departure of Dobbins, who was chosen as health director of the year for North Carolina in 2017. Asabigi and Dobbins did not reply to requests for comment.

“They just don’t leave like that,” Freeman said.

Public health officials are “really getting tired of the ongoing pressures and the blame game,” Freeman said. She warned that more departures could be expected in the coming days and weeks as political pressure trickles down from the federal to the state to the local level.

From the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, federal public health officials have complained of being sidelined or politicized. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been marginalized; a government whistleblower said he faced retaliation because he opposed a White House directive to allow widespread access to the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment.

In Hawaii, U.S. Rep. Tulsi Gabbard called on the governor to fire his top public health officials, saying she believed they were too slow on testing, contact tracing and travel restrictions. In Wisconsin, several Republican lawmakers have repeatedly demanded that the state’s health services secretary resign, and the state’s conservative Supreme Court ruled 4-3 that she had exceeded her authority by extending a stay-at-home order.

With the increased public scrutiny, security details — like those seen on a federal level for Dr. Anthony Fauci, the top infectious disease expert — have been assigned to state health leaders, including Georgia’s Dr. Kathleen Toomey after she was threatened. Ohio’s Dr. Amy Acton, who also had a security detail assigned after armed protesters showed up at her home, resigned Thursday.

In Orange County, in late May, nearly a hundred people attended a county supervisors meeting, waiting hours to speak against an order requiring face coverings. One person suggested that the order might make it necessary to invoke Second Amendment rights to bear arms, while another read aloud the home address of the order’s author — the county’s chief health officer, Dr. Nichole Quick — as well as the name of her boyfriend.

Quick, attending by phone, left the meeting. In a statement, the sheriff’s office later said Quick had expressed concern for her safety following “several threatening statements both in public comment and online.” She was given personal protection by the sheriff.

But Monday, after yet another public meeting that included criticism from members of the board of supervisors, Quick resigned. She could not be reached for comment. Earlier, the county’s deputy director of public health services, David Souleles, retired abruptly.

An official in another California county also has been given a security detail, said Kat DeBurgh, the executive director of the Health Officers Association of California, declining to name the county or official because the threats have not been made public.

DeBurgh is worried about the impact these events will have on recruiting people into public health leadership.

“It’s disheartening to see people who disagree with the order go from attacking the order to attacking the officer to questioning their motivation, expertise and patriotism,” said DeBurgh. “That’s not something that should ever happen.”

Many local health leaders, accustomed to relative anonymity as they work to protect the public’s health, have been shocked by the growing threats, said Theresa Anselmo, the executive director of the Colorado Association of Local Public Health Officials.

After polling local health directors across the state at a meeting last month, Anselmo found about 80% said they or their personal property had been threatened since the pandemic began. About 80% also said they’d encountered threats to pull funding from their department or other forms of political pressure.

To Anselmo, the ugly politics and threats are a result of the politicization of the pandemic from the start. So far in Colorado, six top local health officials have retired, resigned or been fired. A handful of state and local health department staff members have left as well, she said.

“It’s just appalling that in this country that spends as much as we do on health care that we’re facing these really difficult ethical dilemmas: Do I stay in my job and risk threats, or do I leave because it’s not worth it?” Anselmo asked.

Some of the online abuse has been going on for years, said Bill Snook, a spokesperson for the health department in Kansas City, Missouri. He has seen instances in which people took a health inspector’s name and made a meme out of it, or said a health worker should be strung up or killed. He said opponents of vaccinations, known as anti-vaxxers, have called staffers “baby killers.”

The pandemic, though, has brought such behavior to another level.

In Ohio, the Delaware General Health District has had two lockdowns since the pandemic began — one after an angry individual came to the health department. Fortunately, the doors were locked, said Dustin Kent, program manager for the department’s residential services unit.

Angry calls over contact tracing continue to pour in, Kent said.

In Colorado, the Tri-County Health Department, which serves Adams, Arapahoe and Douglas counties near Denver, has also been getting hundreds of calls and emails from frustrated citizens, deputy director Jennifer Ludwig said.

Some have been angry their businesses could not open and blamed the health department for depriving them of their livelihood. Others were furious with neighbors who were not wearing masks outside. It’s a constant wave of “confusion and angst and anxiety and anger,” she said.

Then in April and May, rocks were thrown at one of their office’s windows — three separate times. The office was tagged with obscene graffiti. The department also received an email calling members of the department “tyrants,” adding “you’re about to start a hot-shooting … civil war.” Health department workers decamped to another office.

Although the police determined there was no imminent threat, Ludwig stressed how proud she was of her staff, who weathered the pressure while working round-the-clock.

“It does wear on you, but at the same time we know what we need to do to keep moving to keep our community safe,” she said. “Despite the complaints, the grievances, the threats, the vandalism — the staff have really excelled and stood up.”

The threats didn’t end there, however: Someone asked on the health department’s Facebook page how many people would like to know the home addresses of the Tri-County Health Department leadership. “You want to make this a war??? No problem,” the poster wrote.

Back in Colorado’s Rio Grande County, some members of the community have rallied in support of Brown with public comments and a letter to the editor of a local paper. Meanwhile, COVID-19 case counts have jumped from 14 to 49 as of Wednesday.

Brown is grappling with what she should do next: dive back into another strenuous public health job in a pandemic, or take a moment to recoup?

When she told her 6-year-old son she no longer had a job, he responded: “Good — now you can spend more time with us.”

When protests broke out against the coronavirus lockdown, many public health experts were quick to warn about spreading the virus. When protests broke out after George Floyd’s death, some of the same experts embraced the protests. That’s led to charges of double standards among scientists.

Why it matters: Scientists who are seen as changing recommendations based on political and social priorities, however important, risk losing public trust. That could cause people to disregard their advice should the pandemic require stricter lockdown policies.

What’s happening: Many public health experts came out against public gatherings of almost any sort this spring — including protests over lockdown policies and large religious gatherings.

Yes, but: Spending time in a large group, even outdoors and wearing masks — as many of the protesters are — does raise the risk of coronavirus transmission, says Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

The difference in tone between how some public health experts are viewing the current protests and earlier ones focused on the lockdowns themselves was seized upon by a number of critics, as well as the Trump campaign.

The current debate underscores a larger question: What role should scientists play in policymaking?

The big picture: The debate risks exacerbating a partisan divide among Americans in their reported trust in scientists.

What to watch: If there is a rise in new cases in the coming weeks, there will be pressure to trace them — to protests, rallies and the reopening of states. How experts weigh in could affect how their recommendations will be viewed in the future — and whether the public, whatever their political leanings, will follow them again.

Nobody in Congress likes to give other politicians money. But the track record shows that writing checks directly to states could keep the recession from becoming way worse.

The last time the American economy tanked and Washington debated how to revive it, White House economists pushed one option that had never been tried in a big way: Send truckloads of federal dollars to the states.

When President Barack Obama took office in January 2009 during the throes of the Great Recession, tax revenues were collapsing and state budgets were hemorrhaging. The Obama team was terrified that without a massive infusion of cash from Congress, governors would tip the recession into a full-blown depression by laying off employees and cutting needed services. So the president proposed an unprecedented $200 billion in direct aid to states, a desperate effort to stop the bleeding that amounted to one-fourth of his entire stimulus request.

But the politics were dismal. Republican leaders had already decided to oppose any Obama stimulus. And even Washington Democrats who supported their new leader’s stimulus weren’t excited to help Republican governors balance their budgets. Most politicians enjoy spending money more than they enjoy giving money to other politicians to spend. And since state fiscal relief was a relatively new concept, the Obama team’s belief that it would provide powerful economic stimulus was more hunch-based than evidence-based.

Ultimately, the Democratic Congress approved $140 billion in state aid—only two-thirds of Obama’s original ask, but far more than any previous stimulus.

And it worked. At least a dozen post-recession studies found state fiscal aid gave a significant boost to the economy—and that more state aid would have produced a stronger recovery. The Obama team’s hunch that helping states would help the nation turned out to be correct.

But evidence isn’t everything in Washington. Now that Congress is once again debating stimulus for a crushed economy—and governors are once again confronted with gigantic budget shortfalls—a partisan war is breaking out over state aid. Memories of 2009 have faded, and the politics have scrambled under a Republican presidential administration.

Democratic leaders have made state aid a top priority now that Donald Trump is in the White House, securing $150 billion for state, local and tribal governments in the CARES Act that Congress passed in March, and proposing an astonishing $915 billion in the HEROES Act that the House passed in May. Republican leaders accepted the fiscal relief in the March bill, but they kept it out of the last round of stimulus that Congress enacted in April, and they have declared the HEROES Act dead on arrival. Though they’re no longer denouncing stimulus as socialism, as they did in the Obama era, they’ve begun attacking state aid as a “blue-state bailout.”

Polls show that most voters want Washington to help states avoid layoffs of teachers, police officers and public health workers, but Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, Fox News personalities, and other influential Republicans are trying to reframe state aid as Big Government Democratic welfare spending. Trump doesn’t want to run for reelection during a depression, and he initially suggested he supported state aid, but in recent weeks he has complained that it would just reward Democratic mismanagement.

“There wasn’t a lot of evidence that state aid would be good stimulus in 2009, but now there’s a lot of data, and it all adds up to juice for the economy,” Moody’s chief economist Mark Zandi says. “It’s baffling that this is getting caught up in politics. If states don’t get the support they need soon, they’ll eliminate millions of jobs and cut spending at the worst possible time.”

The coronavirus is ravaging state budgets even faster than the Great Recession did, drying up revenue from sales taxes and income taxes while ratcheting up demand for health and unemployment benefits. But as Utah Republican Senator Mitt Romney pointed out earlier this month: “Blue states aren’t the only ones who are getting screwed.” Yes, California faces a $54 billion budget shortfall, and virus-ravaged blue states like New York and New Jersey are also confronting tides of red ink. But the Republican governors of Texas, Georgia and Ohio have also directed state agencies to prepare draconian spending cuts to close massive budget gaps.

Fiscal experts say the new Republican talking point that irresponsible states brought these problems on themselves with unbalanced budgets and out-of-control spending has little basis in reality. Unlike the federal government, which was running a trillion-dollar deficit even before the pandemic, every state except Vermont is required by law to balance its budget every year. State finances were unusually healthy before the crisis hit; overall, they had reserved 7.6 percent of their budgets in rainy day funds, up from 5 percent before the Great Recession.

But now, governors of both parties are now pivoting to austerity, which means more public employees applying for unemployment benefits, fewer state and local services in a time of need, and fewer dollars circulating in the economy as it begins to reopen.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, who has approved a plan to buy up to $500 billion worth of state and local government bonds to help ease their money problems, recently suggested that direct federal aid to states also “deserves a careful look,” which in Fed-speak qualifies as a desperate plea for congressional action.

Nevertheless, some Republicans who traditionally pushed to devolve power from the federal government to the states are now dismissing state aid as a bloated reward for liberal profligacy. Some fiscal conservatives have merely suggested that the nearly trillion-dollar pass-through to states, cities and tribes in the House HEROES bill is too generous given the uncertainties about the downturn’s trajectory. McConnell actually proposed that states in need should just declare bankruptcy, which is not even a legal option. Former Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker wrote a New York Times op-ed titled “Don’t Bail Out the States.” Sean Hannity told his Fox viewers that more fiscal relief would be a tax on “responsible residents of red states,” while Florida Senator (and former Governor) Rick Scott said it would “bail out liberal politicians in states like New York for their unwillingness to make tough and responsible choices.”

It was not so long ago that governors like Walker and Scott were burnishing their own reputations for fiscal responsibility with federal stimulus dollars. Obama’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was a bold experiment in using federal dollars to backstop states in an economic emergency, and its legacy hangs over the debate over today’s emergency.

By the time Obama won the 2008 election, the U.S. economy had already begun to collapse, and his aides had already given him a stimulus memo proposing a $25 billion “state growth fund.” The goal was anti-anti-stimulus: They wanted to prevent state spending cuts and tax hikes that would undo all the stimulus benefits of federal spending increases and tax cuts. The memo warned that states faced at least $100 billion in budget shortfalls, and that “state spending cuts will add to fiscal drag.” Cash-strapped states would also cut funding to local governments, accelerating the doom loop of public-sector layoffs and service reductions, pulling money out of the economy when government ought to be pouring money in.

The memo also warned that the fund might be caricatured as a bailout for irresponsible states and might run counter to the self-interest of politicians who enjoy dispensing largesse: “Congress may resist spending money that governors get credit for spending.” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California wasn’t keen on creating a slush fund for her state’s Republican governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and House Majority Whip James Clyburn of South Carolina was even more suspicious of his GOP governor, Mark Sanford, an outspoken opponent of all stimulus and most aid to the poor.

After President-elect Obama addressed a National Governors Association event in Philadelphia, Sanford and other conservative Republicans publicly declared that they didn’t want his handouts—and many congressional Democrats were inclined to grant their wish. Even Obama’s chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel, was worried about the politics of writing checks to governors who might run against Obama in 2012 on fiscal responsibility platforms.

There were plenty of studies suggesting that unemployment benefits and other aid to recession victims was good economic stimulus, because families in need tend to spend money once they get it, but there wasn’t much available research about aid to states. Congress had approved $20 billion in additional Medicaid payments to states in a 2003 stimulus package, but that aid had arrived much too late to make a measurable difference in the much milder 2001 recession.

Still, Obama’s economists speculated that state aid would have “reasonably large macroeconomic bang for the buck.” And the holes in state budgets were expanding at a scary pace, doubling in the first week after Obama’s election, increasing more than fivefold by Inauguration Day; Robert Greenstein of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities remembers giving the Obama team frequent updates on state budget outlooks that seemed to deteriorate by the hour.

Obama ended up requesting $200 billion in state fiscal relief in the Recovery Act, eight times his team’s suggestion from November, 10 times more than Congress had authorized in 2003. Emanuel insisted on structuring the aid through increases in existing federal support for schools and Medicaid, rather than just sending states money, so it could be framed as saving the jobs of teachers and nurses. (One otherwise prescient memo by Obama economic aide Jason Furman suggested the unwieldy title of “Tax Increase and Teacher & Cop Layoff Prevention Fund.”) Republicans overwhelmingly opposed the entire stimulus, so Democrats dictated the contents, and they grudgingly agreed to most of their new president’s request for state bailouts.

“State aid was the part of the stimulus where Obama met the most resistance from Democrats,” Greenstein says. “It had such a huge price tag, and nobody loved it. But we can see how desperately it was needed.”

The Obama White House initially estimated that each dollar sent to states would generate $1.10 in economic activity, compared with $1.50 for aid to vulnerable families or infrastructure projects that had been considered the gold standard for emergency stimulus. But later work by Berkeley economist Gabriel Chodorow-Reich and others concluded the actual multiplier effect of the Medicaid assistance in the Recovery Act was as high as $2.00. In addition to preventing cuts in medical care for the poor, it saved or created about one job for every $25,000 of federal spending—and the help arrived much faster than even the most “shovel-ready” infrastructure projects, landing in state capitals just a week after the stimulus passed.

“There were at least a dozen papers written on the state aid, and the evidence is crystal clear that it helped,” says Furman, who is now an economics professor at Harvard. “Unfortunately, it was incredibly hard to get Congress to do more of it, and that hurt.”

After all the bluster about turning down Obama’s money, the only Republican governor who even tried to reject a large chunk of the federal stimulus was Sanford, who was overruled by his fellow Republicans in the South Carolina Legislature. Sarah Palin of Alaska did turn down some energy dollars, while Walker and Scott sent back aid for high-speed rail projects approved by their Democratic predecessors, but otherwise the governors all used the cash to help close their budget gaps. Bobby Jindal of Louisiana appeared at the ribbon-cutting for one Recovery Act project wielding a giant check with his own name on it. Rick Perry of Texas used stimulus dollars to renovate his governor’s mansion—which, in fairness, had been firebombed.

Nevertheless, the Recovery Act covered only about 25 percent of the state budget shortfalls, and Republican senators blocked or shrank Obama’s repeated efforts to send more money to states, forcing governors of both parties to impose austerity programs that slashed about 750,000 state and local government jobs. In 2010, 24 states laid off public employees, 35 cut funding for K-12 education, 37 cut prison spending, and 37 cut money for higher education, one reason for the sharp increases in student loan debt since then. In a recent academic review of fiscal stimulus during the Great Recession, Furman estimated that if state and local governments had merely followed their pattern in previous recessions, spending more to counteract the slowdown in the private sector, GDP growth would have been 0.5 percent higher every year from 2009 through 2013.

The Recovery Act helped turn GDP from negative to positive within four months of its passage, launching the longest period of uninterrupted job growth in U.S. history. But there’s a broad consensus among economists that austerity in the form of layoffs and reduced services at the state and local level worked against the stimulus spending at the federal level, weakening the recovery and making life harder for millions of families.

“The states would’ve made much bigger cuts without the Recovery Act, but they did make big cuts,” says Brian Sigritz, director of fiscal studies at the National Association of State Budget Officers. “We’re seeing similar reactions now, except the situation is even worse.”

It took a decade for state budgets to recover completely from the financial crisis. 2019 was the first year since the Great Recession that they grew faster than their historic average, and the first year in recent memory that no state had to make midyear cuts to get into balance. Rainy-day funds reached an all-time high.

And then the pandemic arrived.

The government sector shed nearly a million jobs in April alone, which is more jobs than it lost during the entire Great Recession. The fiscal carnage has not been limited to states like New York and New Jersey at the epicenter of the pandemic; oil-dependent states like Texas and tourism-dependent states like Florida have also seen revenues plummet. The bipartisan National Governors Association has asked Congress for $500 billion in state stabilization funds, warning that otherwise governors will be forced to make “drastic cuts to the programs we depend on to provide economic security, educational opportunities and public safety.”

So far, Congress has passed four coronavirus bills providing about $3.6 trillion in relief, including $200 billion in direct aid to state, local and tribal governments for Medicaid and other pandemic-related costs. Republican Governor Charlie Baker of Massachusetts says the aid has come in handy in fighting the virus—not only for providing health care and buying masks but for helping communities install plexiglass in consumer-facing offices and pay overtime to essential workers. Massachusetts had more than 10 percent of its expected tax revenues in its rainy-day fund before the crisis, but its revenues have dried up, putting tremendous pressure on the state as well as its 351 local governments.

“You don’t want states and locals to constrict when the rest of the economy is trying to take off,” Baker said. “So far, we’ve gotten close to what we need, but the question is what happens now, because no one knows what the world is going to look like in a few months.”

In the initial coronavirus bills, Democrats pushed for state aid, and Republicans relented. But in the most recent stimulus that Congress enacted, the $733 billion April package focused on small-business lending, Democrats pushed for state aid and Republicans refused. McConnell has said he’s open to another stimulus package, but he has ridiculed the $3 trillion Democratic HEROES Act as wildly excessive, and rejected its huge proposal for state relief as a bailout for irresponsible blue states with troubled pension funds. Sean Hannity expanded the critique, warning Fox viewers that they were being set up to help Democratic states pay off their “unfunded pensions, sanctuary state policies, massive entitlements, reckless spending on Green New Deal nonsense, and hundreds of millions of dollars of waste.”

In fact, the state with the most underfunded pension plan is McConnell’s Kentucky, which has just a third of the assets it needs to cover its obligations, even though it had unified Republican rule until a Democrat rode the pension crisis to the governor’s office last fall. In general, red states tend to be more dependent on federal largesse than blue states, which tend to pay more taxes to the federal government; an analysis by WalletHub found that 13 of the 15 most dependent states voted for Trump in 2016, with Kentucky ranking third.

Trump initially suggested state aid was “certainly the next thing we’re going to be discussing,” before embracing McConnell’s message that state bailouts would unfairly reward incompetent Democrats in states like California. But California’s finances were also in solid shape before the pandemic, with a $5 billion surplus announced earlier this year in addition to a record $17 billion socked away in its rainy-day fund. Some of the partisan arguments against state aid have been flagrantly hostile to economic evidence; Walker’s op-ed actually blamed the state budget shortfalls after the Great Recession on “the disappearance of federal stimulus funds,” rather than the recession itself, as if the stimulus funds somehow created the holes by failing to continue to plug them.

But plenty of Republican politicians support state aid, especially in states that need it the most. The GOP chairmen of Georgia’s appropriations committees recently asked their congressional delegation to support relief “to close the unprecedented gap in dollars required to maintain a conservative and lean government framework of services.” Some Republicans believe McConnell’s opposition to state fiscal relief is just a negotiating ploy, so he can claim he’s making a concession when it gets included in the next stimulus bill.

“Some aid to states is inevitable and necessary,” says Republican lobbyist Ed Rogers. “I suspect McConnell just wants to set a marker, and make sure aid to states doesn’t become aid to pension funds and public employee union coffers.”

That said, it’s not just Republican partisans who are skeptical of the Democratic push for nearly a trillion dollars in state and local aid. The current projections of state budget gaps range as high as $650 billion over the next two years, but some deficit hawks question whether it’s necessary to fill all of them before it’s clear how long the economic pain will last, and before the Fed has even begun its government bond-buying program. Maya MacGuineas, president of the Center for a Responsible Federal Budget, was already disgusted by the trillion-dollar deficits that Washington ran up before the pandemic, and while she says it makes sense to add to those deficits to prevent states from making the crisis worse with radical budget cuts, she doesn’t think federal taxpayers need to cater to every state-level request.

“We have a little time to catch our breath now, so we should make sure that we’re only getting states what they need,” MacGuineas says. “It’s not a moment to be padding the asks.”

Tom Lee, a Republican state senator and former Senate president, says it’s impossible to know how much help states will need without knowing how quickly the economy will reopen, whether there will be a second wave of infections, when Americans will return to their old travel habits, and at what point there will be treatment or a vaccine for the virus. More than three-quarters of Florida’s general revenue comes from sales taxes, so a lot depends on when Floridians start buying things again, and how much they’re willing to buy. Lee says it’s reasonable to expect Washington to help in an emergency, since the national government can print money and Florida can’t, but that the federal money store can’t be open indefinitely, since Florida’s finances were in much better shape than Washington’s before the emergency.

“No question, we need help, but we can’t expect the feds to make us whole,” Lee says. “We’re going to have to tighten our belts, too.”

That’s exactly what Keynesian economic stimulus is supposed to avoid: the contraction of public-sector spending at a time when private-sector spending has already shriveled. A recent poll by the liberal group Data for Progress found that 78 percent of Americans supported $1 trillion in federal aid to states so they can “avoid making deep cuts to government programs and services.”

But Obama White House veterans say they learned two related lessons from their experience with state fiscal relief: It’s better to get too much than not enough, and it’s unwise to assume you can get more later. Stimulus fatigue was real in 2009, and it seems to be returning to Washington. Republicans who spent much of the Obama era screaming about the federal deficit have embraced a free-spending culture of red ink under Trump, but lately they’re starting to talk more about slowing down—not only with state aid, but especially with state aid.

“We’ve already seen how state contraction can undo federal expansion,” Furman says. “This is the one part of the economy where we know exactly what needs to be done, and we don’t need to invent a brand new creative idea. But I worry that we’re not going to do it.”

Despite the president’s opposition, states are increasingly reducing barriers to what many see as the safest way to vote amid the pandemic.

By threatening online on Wednesday to withhold federal grants to Michigan and Nevada if those states send absentee ballots or applications to voters, President Trump has taken his latest stand against what is increasingly viewed as a necessary option for voting amid a pandemic.

What he hasn’t done is stop anyone from getting an absentee ballot.

In the face of a pandemic, what was already limited opposition to letting voters mail in their ballots has withered. Eleven of the 16 states that limit who can vote absentee have eased their election rules this spring to let anyone cast an absentee ballot in upcoming primary elections — and in some cases, in November as well. Another state, Texas, is fighting a court order to do so.

Four of those 11 states are mailing ballot applications to registered voters, just as Michigan and Nevada are doing. And that doesn’t count 34 other states and the District of Columbia that already allow anyone to cast an absentee ballot, including five states in which voting by mail is the preferred method by law.

“Every once in a while you get the president of the United States popping up and screaming against vote-by-mail, but states and both political parties are organizing their people for it,” said Michael Waldman, the president of the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University. “It’s a bizarre cognitive dissonance.”

Many of the states that have relaxed their rules have done so only for pending primary elections, leaving the possibility that they could choose not to do so in November. But that is highly unlikely, said Daniel A. Smith, a University of Florida political scientist and expert on mail ballots.

“The horse is out of the barn whether it’s primaries or the general election,” he said. “The optics are such that states will be under enormous pressure to continue to allow mail voting in the fall.”

Even as the president has offered support for some groups of absentee voters like older Americans and military serving abroad — and even as he votes absentee himself — Mr. Trump has regularly warned with no factual basis that allowing widespread voting by mail was a recipe for election theft. “You get thousands and thousands of people sitting in somebody’s living room, signing ballots all over the place,” Mr. Trump said at a White House briefing last month.

Despite ballot stuffing scandals in the nation’s past, and an absentee vote scandal involving Republicans in North Carolina in 2018, nothing remotely comparable has been documented in modern American politics or linked to voting by mail.

Still, some conservative advocacy groups have embraced Mr. Trump’s view, even going to court to block the expansion of absentee balloting during the pandemic. Republican-controlled legislatures in Louisiana and Oklahoma also have bridled at making voting easier. More legal battles ahead of the November election seem certain.

But in many other states, governments controlled by each of the political camps have moved in the other direction.

In lawsuits and elsewhere, voting-rights advocates and Democrats have taken aim at state rules on voting that they see as discriminatory. In Texas, a federal court ruled this week that a state regulation granting blanket absentee-ballot privileges to voters over 65 — a not-uncommon exception nationally — discriminated against younger voters.

Elsewhere, lawsuits have sought to expand a common exception allowing absentee voting by people too sick to go to the polls. The goal is to cover voters who fear catching the coronavirus while in line at a polling place. A number of states have adopted that view, ruling that voters who reasonably fear exposure to the virus have a right to vote remotely.

Jocelyn Benson, the Democratic secretary of state in Michigan, said this week that the state would mail applications for absentee ballots to all 7.7 million registered voters for both the August primary and the November general election. The Legislature in deeply Republican South Carolina expanded absentee voting rights last week as a lawsuit pressing that cause lay before the state’s Supreme Court.

In West Virginia, the Republican secretary of state sent absentee ballot applications last month to each of the state’s 1.2 million registered voters; so far, nearly one in five has asked to vote absentee.

And in Kentucky, Republicans and Democrats agreed three weeks ago on an emergency plan that allows any voter to request an absentee ballot online and submit it by mail or at drop-off points for two weeks before the state’s June 23 primary. Michael G. Adams, the Republican secretary of state, told National Public Radio last week that he had been excoriated by his party for mailing postcards to voters explaining the new rules.

“The biggest challenge I have right now is making the concept of absentee voting less toxic for Republicans,” said Mr. Adams, who won election on a platform underscoring the threat of voter fraud.

Many political analysts say they find that odd. Until now, the decade-long crusade by Republicans against voter fraud has focused largely on requiring ID cards at polling places, supposedly to counter the distant possibility that an impersonator might make it into a voting booth. Studies show that fraud among absentee voters, while still rare, is more common — but that those voters have tended to be both older and white, a demographic that favors Republicans and Mr. Trump.

“Before 2018, Republicans loved mail balloting,” Michael McDonald, a University of Florida political science professor and elections expert, said this week.

Mr. Trump said in March that Democrat-backed election proposals for expanded voting by mail would ensure that “you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.” Indeed, many Republicans and Democrats alike believe that expanding mail voting would increase Democratic turnout.

Their reasoning is that many more absentee ballots have traditionally been cast by wealthier and more educated voters and expanding voting by mail would add more votes by the low-income and minority voters who tend to lean Democratic and have a harder time getting to polls on Election Day.

But both academic studies and changing demographics throw that into question. Under Mr. Trump, the Republican base has shifted greatly toward whites with less education, while wealthier suburbanites have become increasingly Democratic. Studies in states that use voting by mail indicate it does not favor either party.

And in any case, mail voting is increasingly the norm everywhere: In 2016, nearly one in four voters cast absentee or mail ballots, twice the share just 16 years ago, in 2004.

Mr. McDonald and a number of other experts argue that the greatest threat posed by a shift to voting by mail has nothing to do with fraud. Rather, they say, it is the very real prospect that a tsunami of mail votes could overwhelm both postal workers and election officials, creating a snarl in tallying and certifying votes that would allow a candidate to claim that late-counted votes were fraudulent.

Mr. Trump’s unfounded assertions that mail balloting in Michigan and Nevada encourage fraud suggest that he could be laying the ground for such an scenario, said Richard Hasen, an election law expert at the University of California, Irvine.

“I think he’s trying to undermine confidence in elections,” Mr. Hasen said, citing Mr. Trump’s claim in 2018 that close races for governor and the United States Senate were “massively infected” by fraud until Republican candidates, Ron DeSantis and Rick Scott, prevailed. “Maybe he’s not being conscious about what he’s doing. But he’s acting as if he has a plan.”