https://mailchi.mp/tradeoffs/research-corner-5267789?e=ad91541e82

Earlier this month, the Biden administration officially extended the federal public health emergency (PHE) declaration it had set in place for COVID-19. That means the PHE provisions will stay in effect for another 90 days — until mid-January at least.

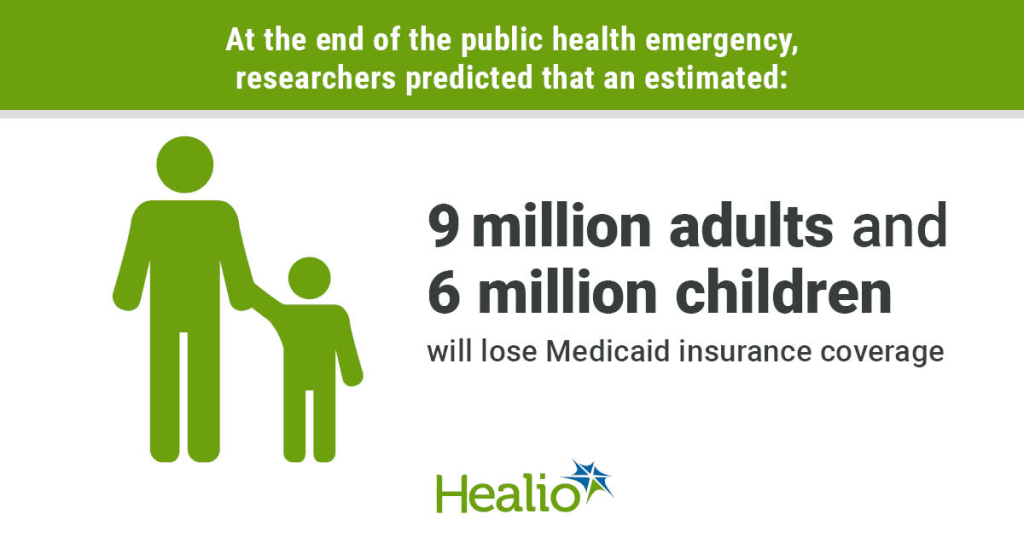

When the PHE does end, a number of rules developed in response to the pandemic will sunset. One of those is a provision that temporarily requires states to let all Medicaid beneficiaries remain enrolled in the program — even if they have become ineligible during the pandemic.

Estimates suggest that millions could lose Medicaid coverage when this emergency provision ends. Among those who would lose coverage because they are no longer eligible for the program, about one-third are expected to qualify for subsidized coverage on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces. Most others are expected to get coverage through an employer. It remains an open question, though, how many people will successfully transition to these other plans.

A recent paper by health economics researcher Laura Dague and colleagues in the Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law sheds light on these dynamics. The authors used a prior change in eligibility in Wisconsin’s Medicaid program to estimate how many people successfully transitioned to a private plan when their Medicaid eligibility ended.

Wisconsin’s Medicaid program is unique. Back in 2008 — before the ACA passed — Wisconsin broadly expanded Medicaid eligibility for non-elderly adults. After the ACA came into effect, Wisconsin reworked its Medicaid program in a way that made about 44,000 adults (mostly parents) with incomes above the federal poverty line ineligible for the program. To remain insured, they would have to switch to private coverage (via Obamacare or an employer).

Using data from the Wisconsin All-Payer Claims Database (APCD), the researchers found that:

- Only about one-third of those 44,000 people had definitely enrolled in private coverage within two months of exiting the Medicaid program.

- The remaining two-thirds of people were uninsured or their insurance status couldn’t be determined.

- Even using the most optimistic assumptions to fill in that missing insurance status data, the authors estimated only up to 42% of people might have had private coverage within three months.

- Nearly 1 in 10 enrollees had re-entered Medicaid coverage within six months, possibly due to fluctuations in household income.

This paper has several limitations. Health insurers are not required to participate in Wisconsin’s APCD, so the authors may not be capturing all successful transitions from Medicaid to private insurance. The paper also does not distinguish between different types of private insurance: Some coverage gains may have resulted from employer-based insurance rather than the ACA marketplace.

Still, the findings suggest that when a large number of Wisconsin residents lost Medicaid eligibility in 2014, many were not able to transition from Medicaid to private coverage. Wisconsin’s experience can help us understand what might happen when the national public health emergency ends and Medicaid programs resume removing people from their rolls.