Exactly 300 years ago, in 1721, Benjamin Franklin and his fellow American colonists faced a deadly smallpox outbreak. Their varying responses constitute an eerily prescient object lesson for today’s world, similarly devastated by a virus and divided over vaccination three centuries later.

As a microbiologist and a Franklin scholar, we see some parallels between then and now that could help governments, journalists and the rest of us cope with the coronavirus pandemic and future threats.

Smallpox strikes Boston

Smallpox was nothing new in 1721. Known to have affected people for at least 3,000 years, it ran rampant in Boston, eventually striking more than half the city’s population. The virus killed about 1 in 13 residents – but the death toll was probably more, since the lack of sophisticated epidemiology made it impossible to identify the cause of all deaths.

What was new, at least to Boston, was a simple procedure that could protect people from the disease. It was known as “variolation” or “inoculation,” and involved deliberately exposing someone to the smallpox “matter” from a victim’s scabs or pus, injecting the material into the skin using a needle. This approach typically caused a mild disease and induced a state of “immunity” against smallpox.

Even today, the exact mechanism is poorly understood and not much research on variolation has been done. Inoculation through the skin seems to activate an immune response that leads to milder symptoms and less transmission, possibly because of the route of infection and the lower dose. Since it relies on activating the immune response with live smallpox variola virus, inoculation is different from the modern vaccination that eradicated smallpox using the much less harmful but related vaccinia virus.

The inoculation treatment, which originated in Asia and Africa, came to be known in Boston thanks to a man named Onesimus. By 1721, Onesimus was enslaved, owned by the most influential man in all of Boston, the Rev. Cotton Mather.

Known primarily as a Congregational minister, Mather was also a scientist with a special interest in biology. He paid attention when Onesimus told him “he had undergone an operation, which had given him something of the smallpox and would forever preserve him from it; adding that it was often used” in West Africa, where he was from.

Inspired by this information from Onesimus, Mather teamed up with a Boston physician, Zabdiel Boylston, to conduct a scientific study of inoculation’s effectiveness worthy of 21st-century praise. They found that of the approximately 300 people Boylston had inoculated, 2% had died, compared with almost 15% of those who contracted smallpox from nature.

The findings seemed clear: Inoculation could help in the fight against smallpox. Science won out in this clergyman’s mind. But others were not convinced.

Stirring up controversy

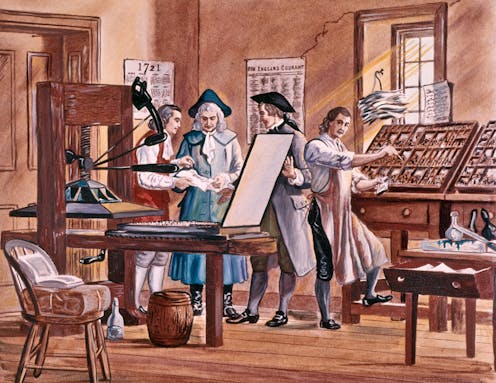

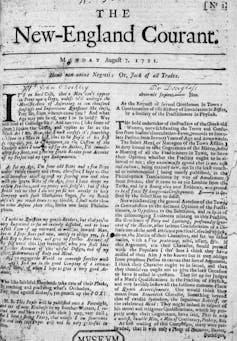

A local newspaper editor named James Franklin had his own affliction – namely an insatiable hunger for controversy. Franklin, who was no fan of Mather, set about attacking inoculation in his newspaper, The New-England Courant.

One article from August 1721 tried to guilt readers into resisting inoculation. If someone gets inoculated and then spreads the disease to someone else, who in turn dies of it, the article asked, “at whose hands shall their Blood be required?” The same article went on to say that “Epidemeal Distempers” such as smallpox come “as Judgments from an angry and displeased God.”

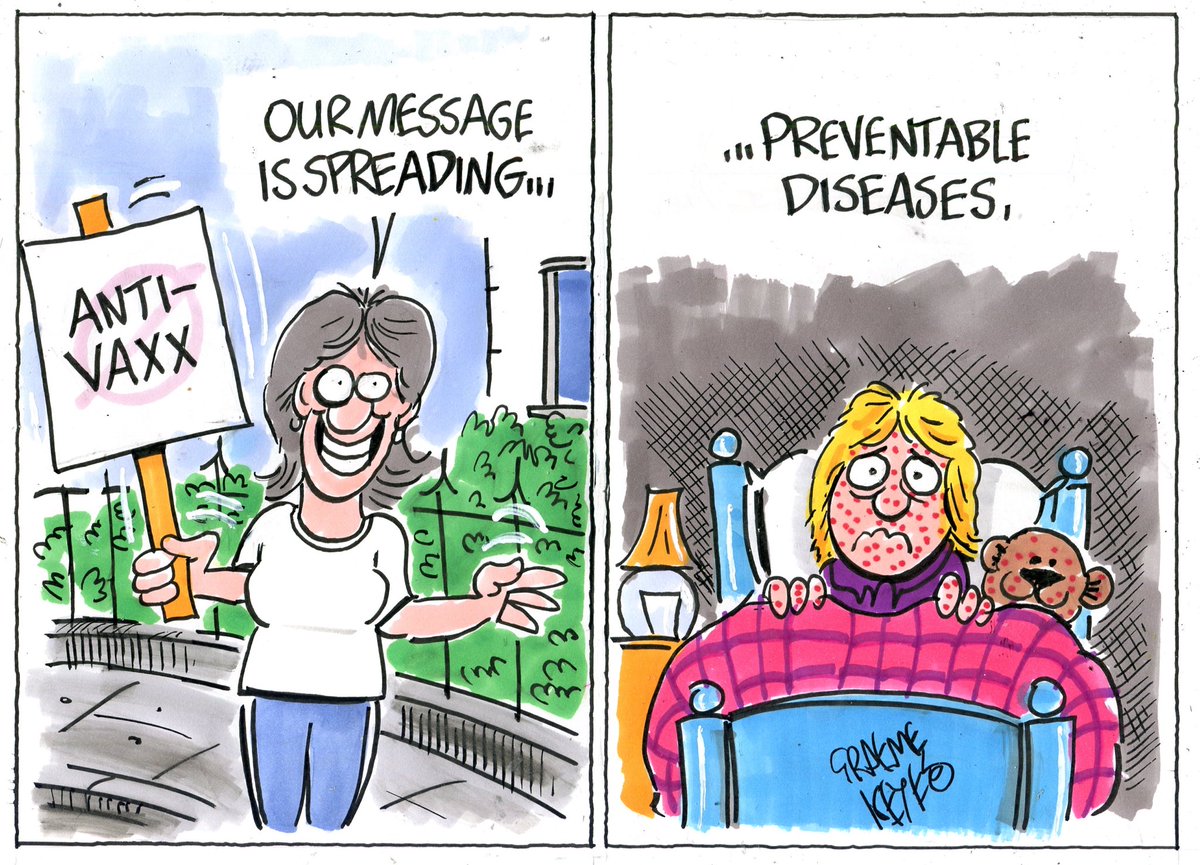

In contrast to Mather and Boylston’s research, the Courant’s articles were designed not to discover, but to sow doubt and distrust. The argument that inoculation might help to spread the disease posits something that was theoretically possible – at least if simple precautions were not taken – but it seems beside the point. If inoculation worked, wouldn’t it be worth this small risk, especially since widespread inoculations would dramatically decrease the likelihood that one person would infect another?

Franklin, the Courant’s editor, had a kid brother apprenticed to him at the time – a teenager by the name of Benjamin.

Historians don’t know which side the younger Franklin took in 1721 – or whether he took a side at all – but his subsequent approach to inoculation years later has lessons for the world’s current encounter with a deadly virus and a divided response to a vaccine.

Independent thought

You might expect that James’ little brother would have been inclined to oppose inoculation as well. After all, thinking like family members and others you identify with is a common human tendency.

That he was capable of overcoming this inclination shows Benjamin Franklin’s capacity for independent thought, an asset that would serve him well throughout his life as a writer, scientist and statesman. While sticking with social expectations confers certain advantages in certain settings, being able to shake off these norms when they are dangerous is also valuable. We believe the most successful people are the ones who, like Franklin, have the intellectual flexibility to choose between adherence and independence.

Truth, not victory

What happened next shows that Franklin, unlike his brother – and plenty of pundits and politicians in the 21st century – was more interested in discovering the truth than in proving he was right.

Perhaps the inoculation controversy of 1721 had helped him to understand an unfortunate phenomenon that continues to plague the U.S. in 2021: When people take sides, progress suffers. Tribes, whether long-standing or newly formed around an issue, can devote their energies to demonizing the other side and rallying their own. Instead of attacking the problem, they attack each other.

Franklin, in fact, became convinced that inoculation was a sound approach to preventing smallpox. Years later he intended to have his son Francis inoculated after recovering from a case of diarrhea. But before inoculation took place, the 4-year-old boy contracted smallpox and died in 1736. Citing a rumor that Francis had died because of inoculation and noting that such a rumor might deter parents from exposing their children to this procedure, Franklin made a point of setting the record straight, explaining that the child had “receiv’d the Distemper in the common Way of Infection.”

Writing his autobiography in 1771, Franklin reflected on the tragedy and used it to advocate for inoculation. He explained that he “regretted bitterly and still regret” not inoculating the boy, adding, “This I mention for the sake of parents who omit that operation, on the supposition that they should never forgive themselves if a child died under it; my example showing that the regret may be the same either way, and that, therefore, the safer should be chosen.”

A scientific perspective

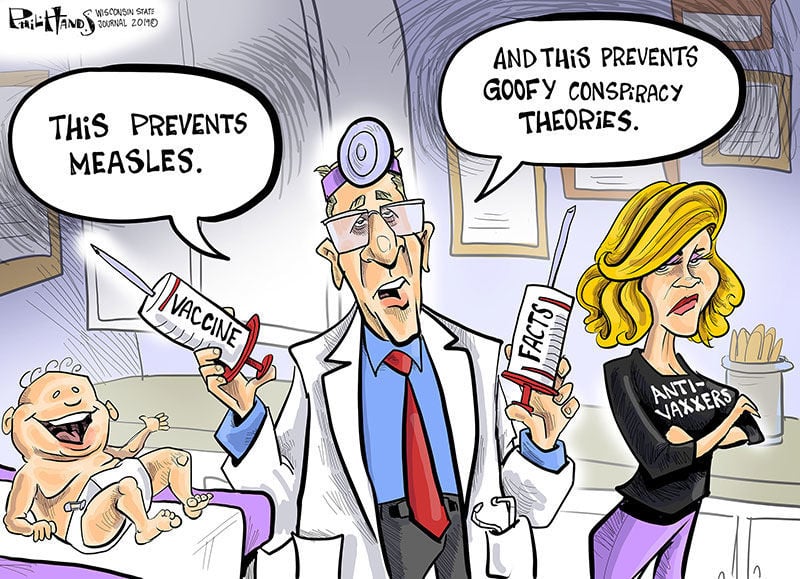

A final lesson from 1721 has to do with the importance of a truly scientific perspective, one that embraces science, facts and objectivity.

Inoculation was a relatively new procedure for Bostonians in 1721, and this lifesaving method was not without deadly risks. To address this paradox, several physicians meticulously collected data and compared the number of those who died because of natural smallpox with deaths after smallpox inoculation. Boylston essentially carried out what today’s researchers would call a clinical study on the efficacy of inoculation. Knowing he needed to demonstrate the usefulness of inoculation in a diverse population, he reported in a short book how he inoculated nearly 300 individuals and carefully noted their symptoms and conditions over days and weeks.

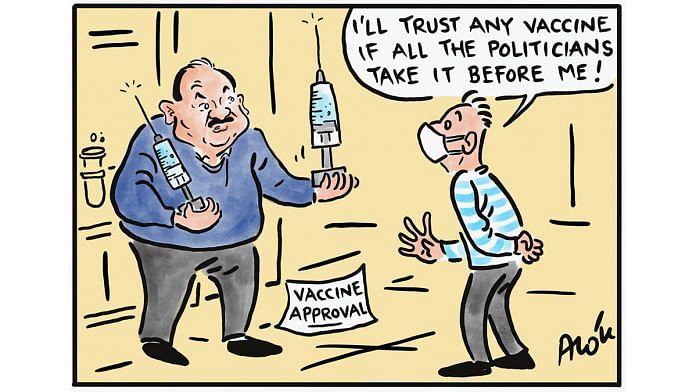

The recent emergency-use authorization of mRNA-based and viral-vector vaccines for COVID-19 has produced a vast array of hoaxes, false claims and conspiracy theories, especially in various social media. Like 18th-century inoculations, these vaccines represent new scientific approaches to vaccination, but ones that are based on decades of scientific research and clinical studies.

We suspect that if he were alive today, Benjamin Franklin would want his example to guide modern scientists, politicians, journalists and everyone else making personal health decisions. Like Mather and Boylston, Franklin was a scientist with a respect for evidence and ultimately for truth.

When it comes to a deadly virus and a divided response to a preventive treatment, Franklin was clear what he would do. It doesn’t take a visionary like Franklin to accept the evidence of medical science today.