The U.S. economy added 467,000 jobs in January as the omicron variant spiked to record heights, with the labor market performing better than many expected two years after the pandemic began.

The unemployment rate ticked up slightly to 4 percent, from 3.9 percent the month before.

The monthly report, released by the Department of Labor, stems from a survey taken in mid-January, around the time the omicron variant was beginning to peak, with close to 1 million new confirmed cases each day. The rapid spread during that period upended many parts of the economy, closing schools, day cares, and a number of businesses, forcing parents to scramble.

But the labor market, according to the new data, performed very well during that stretch.

In addition to the robust January, the Department of Labor also revised upward the figure for December’s jobs report, to 510,000 from 199,000, and November, to 647,000 from 249,000. That means that there were some 700,000 more jobs added at the end of last year than previously estimated — showing a labor market with momentum heading into the new year.

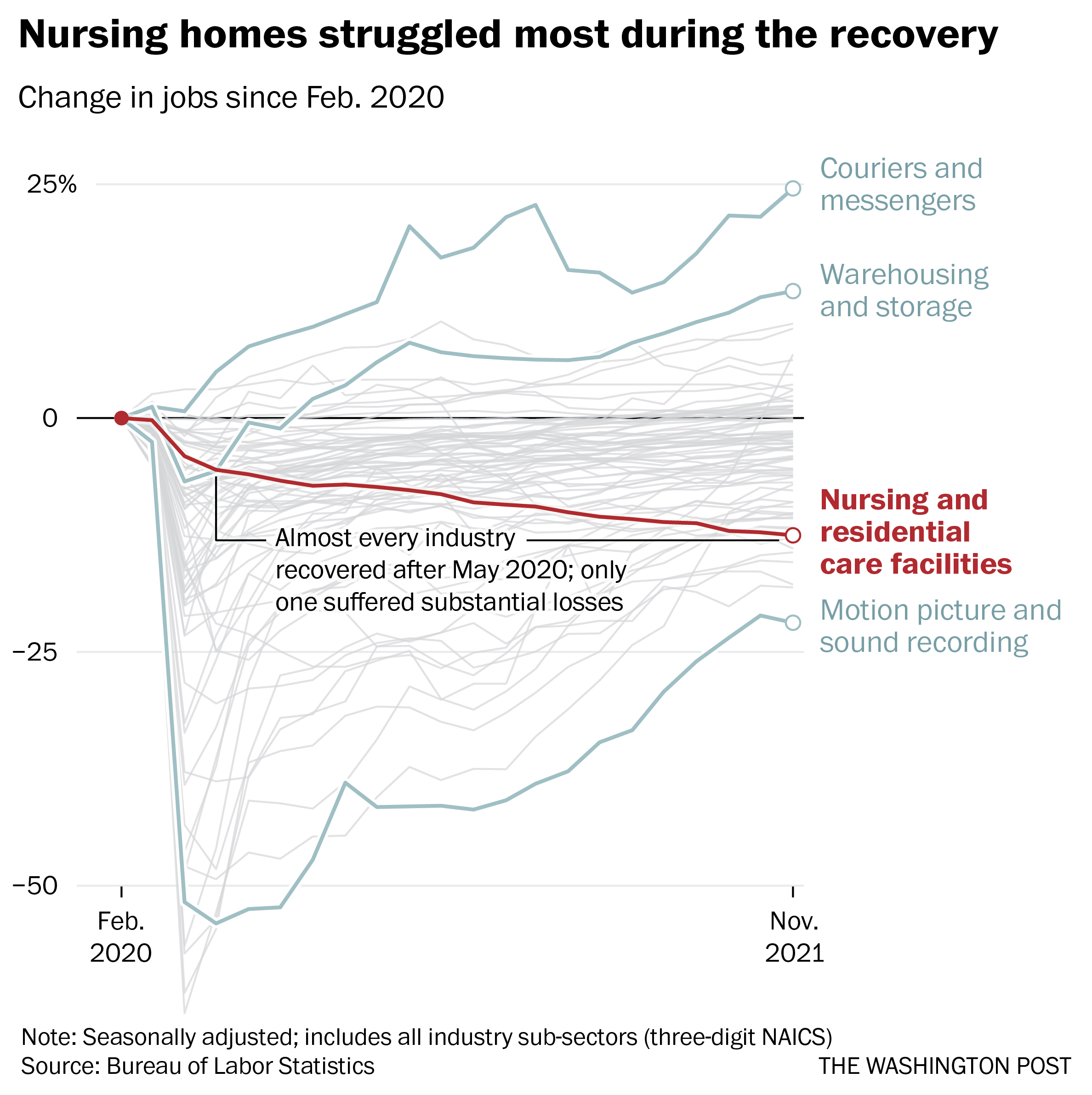

The data sets show a labor market that continues to recover at a strong pace from the pandemic’s worst disruption in March and April of 2020.

New outbreaks and variants have sent shockwaves through the economy since then, but the labor market has continued to return, with companies working to add jobs and wages steadily rising.

The industries experiencing growth in January were lead by the leisure and hospitality sector, which added 151,000 jobs on the month, mostly in restaurants and bars. Professional and business services added 86,000 jobs. Retailers added 61,000 jobs in January, which is typically an off month. Transportation and warehousing added 54,000 jobs.

The labor market’s participation rate, a critical measurement that has never fully recovered from losses during the pandemic’s earliest days, also went up significantly, to 62.2 percent from 61.9 percent. That shows more people are reentering the labor force, looking for work.

Average hourly earnings increased by 23 cents on the month to $31.63, up 5.7 percent over the last year. However, those gains for many people have largely been wiped out by rising prices from inflation.

The data was collected during a tumultuous period. Nearly nine million workers were out sick around the time the survey was taken, and some of them could have been counted as unemployed based on the way the survey is conducted.

January is traditionally a weak month for employment when retail and other industries shed jobs after the holiday season. Economists say that seasonal adjustments made to the survey’s data to account for this have the potential to distort the survey in the other direction, given that the holiday shopping boom appeared to take place earlier this year than typical.

As such, predictions for job growth for the month had been all over the map. Analysts surveyed by Dow Jones predicted an average of about 150,000 jobs added for the month, in what would be the lowest amount added in a year. Some economists predicted job losses, of up to 400,000.

Last year was a strong year for growth in the labor market, with the country adding an average of more than 550,000 jobs a month — regaining some 6.5 million jobs lost in the pandemic’s earlier days, after the Department revised its numbers. The country has about 2.9 million fewer jobs than it had before the pandemic, according to the figures released Friday.

“Omicron is going to make it look like things dropped off a cliff in January, but overall they did not,” said Drew Matus, chief market strategist for MetLife Investment Management.

Some economists like Matus say that the prospects for such rapid regrowth are more complicated this year, with the fiscal measures that boosted the economy during the pandemic’s first two years, like generous government aid, and record low interest rates from federal bankers, having largely expired, and the country’s confidence in a virus-free future dented after the winter wave.

Since the rollout of vaccines last year, there have been hopes that a return to a more typical rhythm of life could encourage some of the roughly two million people who have left the labor force during the pandemic to seek work anew, but thus far, continued threats from variants — and uncertainty after more closures of schools, daycares, and office — have prevented this from materializing in a substantial way.

There are signs that the omicron exacted a toll on the economy during its peak.

Weekly unemployment claims swelled mid-month to its highest level since October, though the numbers have come down in the two weeks since. Other statistical markers like passenger traffic at airports, hotel revenues, and dining reservations also took a hit during the month.

Recent months continue to be marked by incredible churn in the labor market, as record numbers of workers are switching jobs. In December, some 4.3 million people quit or changed jobs — a number which was down from an all-time high in November but still at elevated. Employers continue to report near record numbers of job openings: the Bureau of Labor Statistics said they reported some 10.9 million openings last month.