Category Archives: Uncategorized

Happy Thanksgiving

HAPPY THANKSGIVING

Healthcare Triage: A Lyft to the Hospital: Can Ride Sharing Replace Ambulances?

Healthcare Triage: A Lyft to the Hospital: Can Ride Sharing Replace Ambulances?

An ambulance ride of just a few miles can cost thousands of dollars, and a lot of it may not be covered by insurance. With ride-hailing services like Uber or Lyft far cheaper and now available within minutes in many areas, would using one instead be a good idea?

Perhaps surprisingly, the answer in many cases is yes. That’s the topic of this week’s HCT.

The Health 202: Lame-duck health initiatives look unlikely in Congress

Republicans have a health-care checklist they would like to accomplish before losing their House majority early next year. But they’re well aware Democrats have little incentive to help them out — especially given the growing resistance top House Democrat Nancy Pelosi appears to be facing in her quest to assume the speakership.

Drug and medical device makers are lobbying hard for Congress to roll back legislation that cuts into their bottom lines. The pharmaceutical industry wants a reversal of a requirement passed in a budget deal earlier this year for companies to pay more into the so-called “doughnut hole” in Medicare’s prescription drug program. The medical device industry wants a sales tax imposed through the Affordable Care Act repealed.

There’s also talk of passing a bill with strong bipartisan support — notably from members on both the far right and the far left — that could move the needle toward lower drug prices by making it easier for drug companies to develop generic alternatives. (The Health 202 wrote about this CREATES Act in February).

Hypothetically, there could be room for Congress to advance these initiatives by lumping them into a must-pass bill to keep the government funded past Dec. 7. But lobbyists said they’re pessimistic anything substantial will happen, and aides told me a lot is up in the air.

For one thing, Democrats are already unenthusiastic about giving any ground to the health-care industry, particularly drugmakers. They’re on the cusp of taking charge of the House, a perch from which it will be much easier to advance their own priorities.

For another, Pelosi is unlikely to want to give any reason to incoming Democrats — some of whom vowed on the campaign trail to vote against her — to criticize her for surrendering to Republicans. She’s been furiously courting this new class of freshmen, as Politico detailed, hosting private dinners and receptions in preparation for a Nov. 28 vote inside the Democratic Caucus and a final Jan. 3 vote on the House floor. Rep. Marcia Fudge (D-Ohio), a member of the Congressional Black Caucus, emerged yesterday as a possible challenger to Pelosi, arguing there should be a minority woman in the top echelons of House leadership.

Republicans appear cognizant of these realities. Rep. Greg Walden (R-Ore.), who leads the Energy and Commerce Committee, told a private group yesterday that while he would like to get some of these priorities accomplished, it’s hard to imagine Democrats agreeing to any of them, a lobbyist at the meeting told me.

Still, lawmakers have just arrived back in Washington this week after the midterm elections, and negotiations are just at the beginning stages. Here are the things to be watching on the health policy front:

1. Reversing drugmakers’ extra “doughnut hole” contributions.

The drug industry has been fighting tooth and nail to reverse part of a February spending bill requiring them to give deeper discounts to Medicare enrollees whose spending on drugs is high enough to reach a coverage gap known as the “doughnut hole.” The discount is currently 50 percent for brand-name drugs but is set to rise to 70 percent next year.

The aim of the provision was to reduce out-of-pocket spending for seniors — who are often on a fixed income and struggle to pay for their medications — but it also represented an unusual financial hit for the powerful pharmaceutical industry.

2. Passing the CREATES Act.

Legislators have floated passing this popular bill as a way to get Democrats on board with making the doughnut-hole fix that drugmakers want so badly. As I wrote in February, the CREATES Act tried to even the playing field for generic drug developers who often run up against blockades from branded pharmaceutical companies seeking to keep their competition at bay.

It would allow generic companies to sue branded companies for failing to provide them with samples needed for testing and has an unusually wide range of support from lawmakers, although the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of American predictably hates it.

3. Repealing the medical device tax.

This tax nearly always comes up in discussions about the ACA because the device industry has spent considerable energy trying to chip away at it. The 2.3 percent sales tax was included in the 2010 health-care law as a way to help pay for its insurance subsidies, but Congress has delayed its implementation until 2020. Because that’s still a year away, the long timeline might remove a sense of urgency that could otherwise push Congress to repeal it.

The Health 202: Here’s how Trump and Bernie Sanders agree on lowering drug prices

Have you heard about the trendy new approach to lowering prescription drug spending? Copy other countries.

The Trump administration and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) are strange bedfellows on drug prices. But they’re both eyeing similar approaches to lowering the country’s astronomically high spending on prescription medicines: pegging U.S. drug prices to lower international levels.

Sanders proposed a bill Tuesday incentivizing companies to develop cheaper generic versions of brand-name medications that the government determines to be “excessively priced” in comparison to the median price in Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Japan.

This is similar to an idea advanced in October by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, whose agency is experimenting with pegging some Medicare payments to an index based on sales prices in those five countries plus 11 more: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Finland, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain and Sweden.

Both proposals stem from the reality that drug prices are much higher in the United States because the government doesn’t engage in price-setting, unlike in many other countries with similar economies. That means pharmaceutical companies pocket a lot more money in this country — and rely more heavily on their U.S. profits to pay for developing new medications.

Trump and Sanders have adopted similar rhetoric when they talk about the issue, even though the Republican president and the self-described democratic socialist senator couldn’t be further apart on other topics such as taxes and immigration. The United States pays unfairly high prices for prescription drugs, they argue, even as other countries demand — and obtain – steep discounts.

It’s not the first time Trump and Sanders have shared common ground. During their 2016 campaigns, both candidates advocated allowing Medicare’s prescription drug program to directly negotiate lower prices with drugmakers and private companies. Trump has since backed away from that idea, but HHS surprised many with its bold suggestion of creating an international price index (which I explained in this Health 202).

Granted, HHS’s experiment is quite limited in scope. It applies only to drugs administered to Medicare patients by doctors themselves and will last just five years. The experiment — called a “demonstration” in administration-speak — won’t start until sometime after the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services propose a rule early next year.

Sanders’s proposal, also sponsored by Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), would go much further by affecting all drugs, including those purchased by Americans with private health insurance. If HHS determined a drug price to be excessive, the secretary would be directed to strip its maker of exclusivity rights and open the door for competitors to develop a generic version.

Sanders gave a nod to Trump’s Part B proposal but emphasized that his approach would help the more than 150 million Americans who get private health coverage from their employer. The monthly cost for the popular insulin Lantus (used for diabetes) could fall from $387 to $220 and the medication Humira (used for arthritis) could fall from $2,770 to $1,576, according to some examples provided by Sanders’s office.

There’s little to no chance Sanders’s bill will advance in Congress. Many Republicans aren’t enthused even about Trump’s limited Part B demonstration, because it smacks of government price-setting.

There is something else Sanders shares with the president: strong resistance from the pharmaceutical industry. A spokeswoman for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America said both proposals would be “devastating” if implemented.

“This legislation would have the same devastating impact on patients as the administration’s proposed International Pricing Index model,” PhRMA spokeswoman Nicole Longo said in a statement provided to The Health 202.

“Patients in countries whose governments set prices wait years for new medicines and have far fewer treatment options,” she added. “These policies reduce investment in research and development, slow progress in creating tomorrow’s cures and will result in Americans having access to fewer new medicines.”

California approves CVS, Aetna merger contingent upon premium promise and $240 million investment

New York State still needs to clear the $69 billion deal that CVS said it expects to close by Thanksgiving.

A California regulator has cleared the way for CVS Health to acquire Aetna.

Thursday, the California Department of Managed Health Care Director Shelley Rouillard approved the acquisition on the promise that CVS and Aetna agree not to increase premiums as a result of acquisition costs. The agreement states premium rate increases overall would be kept to a minimum.

The plans also agree to invest close to $240 million in California’s healthcare delivery system, according to the press release from the Department of Managed Healthcare.

The money includes $166 million for state healthcare infrastructure and employment, such as building and improving facilities and supporting jobs in Fresno and Walnut Creek.

Another $22.8 million would go to increase the number of healthcare providers in underrepresented communities by funding scholarships and loan repayment programs.

An estimated $22.5 million would support joint ventures and accountable care organizations in the delivery of coordinated and value-based care.

WHY THIS MATTERS

California represents one of the last hurdles for the $69 billion merger that CVS has said it expects to see closed by Thanksgiving.

The New York State Department of Financial Services has yet to issue a decision after holding an October 18 hearing on the application.

THE TREND

The Department of Justice has already said that there are no barriers to the companies completing the merger, once CVS and Aetna sell Aetna’s Medicare Part D plans. Aetna is divesting the prescription drug plans to WellCare.

California held a public meeting on the merger on May 2.

ON THE RECORD

“Our primary focus in reviewing a health plan merger is to ensure compliance with the strong consumer protections and financial solvency requirements in state law,” Rouillard said. “The department thoroughly examined this merger and determined enrollees will have continued access to appropriate healthcare services and also imposed conditions that will help increase access and quality of care, remove barriers to care and improve health outcomes.”

Doctors Are Fed Up With Being Turned Into Debt Collectors

Highlighting a key implication of the rise in high-deductible health plans, both on the ACA exchanges and in employer-sponsored insurance, the article describes a question now commonly faced by doctors and hospitals—how best to collect their patients’ portion of the fees they charge? As one Texas doctor tells Bloomberg, reflecting the experience of the Maldonados from the other side of the equation, “If [patients] have to decide if they’re going to pay their rent or the rest of our bill, they’re definitely paying their rent.” He reports that the number of people dodging his calls to discuss payment has increased “tremendously” since the passage of the ACA. Another Texas doctor reports that his small practice had to add an additional full-time staff member just to collect money owed by patients, adding further overhead to his practice’s costs and making it more likely that he, like many other doctors, will eventually seek shelter by being employed by a larger delivery organization. That trend, as has been repeatedly shown, further increases the cost of care, exacerbating the increase in insurance costs for families like the Maldonados. This Gordian knot of increasing costs, rising deductibles, and growing premiums has left us with a healthcare system that’s forcing difficult decisions at every turn, for patients and providers.

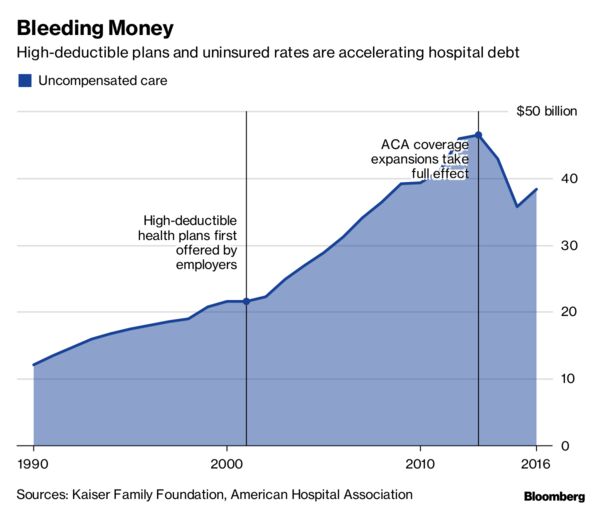

Physicians, hospitals and medical labs are grappling with the rise in high-deductible insurance.

Doctors, hospitals and medical labs used to be concerned about patients who didn’t have insurance not paying their bills. Now they’re scrambling to get paid by the ones who do have insurance.

For more than a decade, insurers and employers have been shifting the cost of care onto their workers and customers, tamping down premiums by raising patients’ out-of-pocket costs. Last year, almost half of privately insured Americans under age 65 had annual deductibles ranging from $1,300 to as high as $6,550, government data show.

“It’s harder to collect from the patient than it is from the insurance,” said Amy Derick, a doctor who heads a dermatology practice outside Chicago. “If the plans change to a higher deductible, it’s harder to get the patients to pay.”

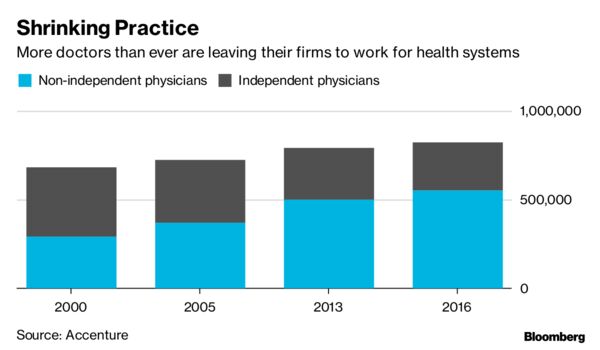

Independent physicians cited reimbursement pressures as their biggest concern for staying in business, according to a report by Accenture Plc in 2015.

“If they have to decide if they’re going to pay their rent or the rest of our bill, they’re definitely paying their rent,” said Gerald “Ray” Callas, president of the Texas Society of Anesthesiologists, whose Beaumont, Texas, practice treats about 40,000 people annually. “We try to work with the patient, but on the other hand, we can’t do it for free because we still maintain a small business.”

In 2016, Callas introduced payment options that allow patients with expensive plans to pay a portion of the bill upfront or on a monthly basis over several years. Even so, Callas said the number of people avoiding his calls after surgery has increased “tremendously” each year since the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010.

Derick instituted a “time-out” option a few years back that gives patients the billing codes before a procedure, allowing them to call their insurance companies for estimates. Even with the program, collection rates are slower, especially at the beginning of the year when insurance plan deductibles reset.

Even large medical companies with national operations are facing the problem. Quest Diagnostics Inc., the lab-testing giant, said 20 percent of services billed to patients in the third quarter of this year went unpaid, costing the company about $80 million in lost revenue.

“We certainly have a high bad-debt rate for the uninsured,” Chief Financial Officer Mark Guinan said in a telephone interview. “But really the biggest driver is people with insurance. It’s their coinsurance and their high deductibles, and they don’t always pay their bills.”

Another testing company, Laboratory Corp. of America Holdings, reported its first year-over-year uptick in unpaid bills in the first quarter of 2016. At the time, Chief Executive Officer David King said high-deductible plans, higher copays and greater incidences of non-covered services led to more dollars being shifted to patients. LabCorp declined requests for comment.

Northwell Healthcare Inc., a network of more than 700 hospitals and outpatient facilities, lost $106.9 million to unpaid services in 2015. Others have reported the same: Acute-care and critical-access hospitals reported$55.9 billion in bad debt for 2015, according to data compiled by the American Hospital Directory Inc.

“High-deductible plans have had a very big impact,” said Richard Miller, Northwell’s chief business strategy officer.

When it comes to reimbursement, a common denominator across the health-care industry is the archaic process through which bills are processed — a web of medical records, billing systems, health insurers and contractors.

High deductibles only add to the red tape. Providers don’t have real-time, fully accurate information on patient deductibles, which fluctuate based on how much has already been paid. That forces providers to constantly reach out to insurance companies for estimates.

Tarek Fakhouri, a Texas surgeon specializing in skin cancer, had to hire an additional staff member just to reason through bills with patients and their insurers, a big expense for an office of six or seven employees. About 10 percent of Fakhouri’s patients need payment plans, delay their skin-cancer surgeries until they’ve met their deductibles, or have to choose an alternative treatment.

According to a study earlier this year by the Journal of American Medical Association, primary-care physicians at academic health-care systems lose about 15 percent of their revenue to billing activities like calling insurance companies for estimates.

“It’s an unnecessary added cost to the health-care system to have to hire staff just to sit there on hold with insurance companies to find out what a patient’s deductible status is,” said Fakhouri.

Callas, Derick, and Fakhouri said they all know physicians who have left private practice altogether, some for the sole purpose of ending their dual roles as bill collectors. According to a study by the American Medical Association, less than half of doctors were self-employed as of 2016 — the lowest total ever. Many left their own practices in favor of hospitals and large physician groups with more resources.

To cope with the challenge, labs and hospitals are investing millions in programs designed to help patients understand what they owe at the point of care. Northwell has been implementing call centers and facilities where patients can ask questions about their bills.

“There’s a burden on both sides,” said Callas. “But health-care providers get caught in the middle.”

Health Systems Need to Completely Reassess How They Manage Costs

https://hbr.org/2018/11/health-systems-need-to-completely-reassess-how-they-manage-costs

A recent Navigant survey found that U.S. hospitals and health systems experienced an average 39% reduction in their operating margins from 2015 to 2017. This was because their expenses grew faster than their revenues, despite cost-cutting initiatives. As I speak with industry executives, a common refrain is “I’ve done all the easy stuff.” Clearly, more is needed. Cost reduction requires an honest and thorough reassessment of everything the health system does and ultimately, a change in the organization’s operating culture.

When people talk about having done “the easy stuff,” they mean they haven’t filled vacant positions and have eliminated some corporate staff, frozen or cut travel and board education, frozen capital spending and consulting, postponed upgrades of their IT infrastructure, and, in some cases, launched buyouts for the older members of their workforces, hoping to reduce their benefits costs.

These actions certainly save money, but typically less than 5% of their total expense base. They also do not represent sustainable, long-term change. Here are some examples of what will be required to change the operating culture:

Contract rationalization. Contracted services account for significant fractions of all hospitals’ operating expenses. The sheer sprawl of these outsourced services is bewildering, even at medium-size organizations: housekeeping, food services, materials management, IT, and clinical staffing, including temporary nursing and also physician coverage for the ER, ICU and hospitalists. More recently, it has come in the form of the swarms of “apps” sold to individual departments to solve scheduling and care-coordination problems and to “bond” with “consumers.” There is great dispersion of responsibility for signing and supervising these contracts, and there is often an unmanaged gap between promise and performance.

An investor-owned hospital executive whose company had acquired major nonprofit health care enterprises compared the proliferation of contracts to the growth of barnacles on the bottom of a freighter. One of his company’s first transition actions after the closure of an acquisition is to put its new entity in “drydock” and scrape them off (i.e., cancel or rebid them). Contractors offer millions in concessions to keep the contracts, he said. Barnacle removal is a key element of serious cost control. For the contracts that remain, and also consulting contracts that are typically of shorter duration, there should be an explicit target return on investment, and the contractor should bear some financial risk for achieving that return. The clinical-services contracts for coverage of hospital units such as the ER and ICU are a special problem, which I’ll discuss below.

Eliminating layers of management. One thing that distinguishes the typical nonprofit from a comparably-sized investor-owned hospital is the number of layers of management. Investor-owned hospitals rarely have more than three or four layers of supervision between the nurse that touches patients and the CEO. In some larger nonprofit hospitals, there may be six. The middle layers spend their entire days in meetings or on conference calls, traveling to meetings outside the hospital, or negotiating contracts with vendors.

In large nonprofit multi-hospital systems, there is an additional problem: Which decisions should be made at the hospital, multi-facility regional, and corporate levels are poorly defined, and as a consequence, there is costly functional overlap. This results in “title bloat” (e.g., “CFOs” that don’t manage investments and negotiate payer or supply contracts but merely supervise revenue cycle activities, do budgeting, etc.). One large nonprofit system that has been struggling with its costs had a “president of strategy,” prima facie evidence of a serious culture problem!

Since direct caregivers are often alienated from corporate bureaucracy, reducing the number of layers that separate clinicians from leadership — reducing the ratio of meeting goers to caregivers — is not only a promising source of operating savings but also a way of letting some sunshine and senior-management attention reach the factory floor.

However, doing this with blanket eliminations of layers carries a risk: inadvertently pruning away the next generation of leadership talent. To avoid this danger requires a discerning talent-management capacity in the human resources department.

Pruning the portfolio of facilities and services. Many current health enterprises are combinations of individual facilities that, over time, found it convenient or essential to their survival to combine into multi-hospital systems. Roughly two-thirds of all hospitals are part of these systems. Yet whether economies of scale truly exist in hospital operations remains questionable. Modest reductions in the cost of borrowing and in supply costs achieved in mergers are often washed out by higher executive compensation, more layers of management, and information technology outlays, leading to higher, rather than lower, operating expenses.

A key question that must be addressed by a larger system is how many facilities that could not have survived on their own can it manage without damaging its financial position? As the U.S. savings and loan industry crisis in the 1980s and 1990s showed us, enough marginal franchises added to a healthy portfolio can swamp the enterprise. In my view, this factor — a larger-than-sustainable number of marginal hospital franchises — may have contributed to the disproportionate negative operating performance of many multi-regional Catholic health systems from 2015 to 2017.

In addition to this problem, many regional systems comprised of multiple hospitals that serve overlapping geographies continue to support multiple, competing, and underutilized clinical programs (e.g., obstetrics, orthopedics, cardiac care) that could benefit from consolidation. In larger facilities, there is often an astonishing proliferation of special care units, ICUs, and quasi-ICUs that are expensive to staff and have high fixed cost profiles.

Rationalizing clinical service lines, reducing duplication, and consolidating special care units is another major cost-reduction opportunity, which, in turn, makes possible reductions in clinical and support personnel. The political costs and disruption involved in getting clinicians to collaborate successfully across facilities sometimes causes leaders to postpone addressing the duplication and results in sub-optimal performance.

Clinical staffing and variation. It is essential to address how the health system manages its clinicians, particularly physicians. This has been an area of explosive cost growth in the past 15 years as the number of physicians employed by hospitals has nearly doubled. In addition to paying physicians the salaries stipulated in their contracts, hospitals have been augmenting their compensation (e.g., by paying them extra for part-time administrative work and being on call after hours and by giving them dividends from joint ventures in areas such as imaging and outpatient surgery where the hospital bears most of the risk).

The growth of these costs rivals those of specialty pharmaceuticals and the maintenance and updating of electronic health record systems. Fixing this problem is politically challenging because it involves reducing physician numbers, physician incomes, or both. As physician employment contracts come up for renewal, health systems will have to ask the “why are we in this business” and “what can we legitimately afford to pay” questions about each one of them. Sustaining losses based on hazy visions of “integration” or unproven theories about employment leading to clinical discipline can no longer be justified.

But this is not the deepest layer of avoidable physician-related cost. As I discussed in this HBR article, hospitals’ losses from treating Medicare patients are soaring because the cost of treating Medicare patient admission is effectively uncontrolled while the Medicare DRG payment is fixed and not growing at the rate of inflation. The result: hospitals lost $49 billion in 2016 treating Medicare patients, a number that’s surely higher now.

The root cause of these losses is a failure to “blueprint,” or create protocols for, routine patient care decisions, resulting in absurd variations in the consumption of resources (operating room time; length of stay, particularly in the ICU; lab and imaging exams per admissions, etc.).

The fact that hospitals have outsourced the staffing of the crucial resource-consuming units such as the ICU and ER makes this task more difficult. Patients need to flow through them efficiently or the hospital loses money, often in large amounts. How many of those contracts obligate the contractual caregivers to take responsibility for managing down the delivered cost of the DRG and reward them for doing so? Is compensation in these contracts contingent on the profit (or loss avoidance) impact of their clinical supervision?

These are all difficult issues, but until they are addressed, many health systems will continue to have suboptimal operating results. While I am not arguing that health systems abandon efforts to grow, unless those efforts are executed with strategic and operational discipline, financial performance will continue to suffer. A colleague once said to me that when he hears about someone having picked all the low-hanging fruit, it is really a comment on his or her height. Given the escalating operating challenges many health systems face, it may be past time for senior management to find a ladder.

Sean Parker: Health care’s big breakthroughs aren’t going to come out of Google or Amazon

Sean Parker: Health care’s big breakthroughs aren’t going to come out of Google or Amazon

Sean Parker, the tech billionaire and cancer research philanthropist, may be a product of a Silicon Valley tech giant — but he’s skeptical about the impact those companies will have as they increasingly make a play in medicine.

“I just don’t think the innovations that are going to drive this revolution in health care and discovery are going to come out of Amazon or Google,” Parker said Tuesday at an event put on by the Washington Post. “Google has a big group that’s focused on this — they’re really smart, they’re not unsophisticated, they’re not naive — but I don’t think that’s where you’re going to see the big breakthroughs happening.”

Silicon Valley’s tech giants have invested significant resources in health care and science in recent years — and attracted big-name talent.

Amazon, along with JPMorgan and Berkshire Hathaway, has launched a new health care company aimed at developing solutions that could be implemented elsewhere in the U.S. health care system.

Alphabet, Google’s parent company, has been scooping up some of the biggest names in health care. Google just hired David Feinberg, the forward-thinking CEO of the Geisinger health system, the Pennsylvania health plan and hospital system confirmed last week. Dr. Toby Cosgrove, the longtime president and CEO of Cleveland Clinic, joined Google earlier this year. And Dr. Robert Califf, the former commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, last year joined Verily, Alphabet’s unit working on solutions to disease.

While coders face their own formidable challenges, Parker said, “tech people coming from tech to biology so dramatically underestimate the complexity of the human body. It’s not designed by us. It doesn’t work in ways that make sense.”

Parker, the former president of Facebook, has since become a major funder of research into therapies that seek to fight cancer by harnessing the patient’s own immune system through his foundation Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy, which he founded in 2016. It has funded prominent research scientists across the country, most notably James Allison, one of the recipients of this year’s Nobel Prize in medicine.