It seems pretty clear the path the United States is on. Within a few months, everyone who wants to be vaccinated against the coronavirus will be, save for those below the minimum age for which vaccines are available. For everyone else, the pandemic Wild West will continue, with the country hopefully somewhere near the level of immunity that will keep the virus from spreading wildly but with large parts of the population — again, including kids — susceptible to infection.

That really gets at one of the two outstanding questions: How many Americans won’t get the vaccine? If the figure is fairly low, the ability of the virus to spread will be far lower. If it’s high, we have a problem. And that’s the other outstanding question: How big of a problem will the virus be, moving forward?

We know that even as vaccines are being rolled out, cases are slowly climbing. While the number of new infections recorded each day is well off the highs seen in the winter, we’re still averaging more cases on a daily basis than we saw even a month into the third wave that began in September. A lot of people are still getting sick, and, even with most elderly Americans now protected with vaccine, a lot more people will probably die.

Data released by Gallup this week shows that both of the questions posed above share a common component. It is, as you probably suspected, those who are least willing to get vaccinated who are also least likely to take steps to contain the virus.

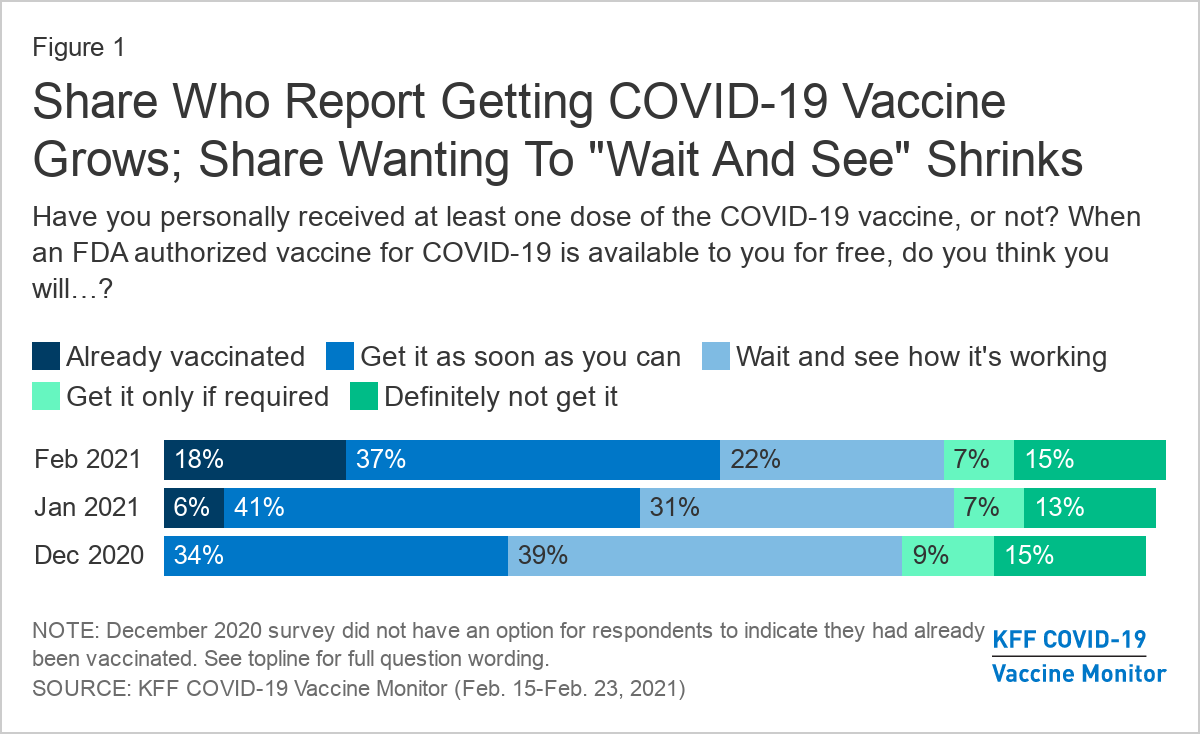

Gallup asked Americans about their vaccination status, finding that about a fifth had been fully vaccinated and an additional 13 percent partially vaccinated. More than a quarter of respondents, though, said they didn’t plan to get vaccinated. It was those in that latter group who were least likely to say that they were completely or mostly isolating in an effort to prevent the virus spreading.

It was also those skeptics who were least likely to say that, in the past seven days, they had avoided crowds, group gatherings or travel. If you’re not inclined to get vaccinated, it is at least consistent that you would be similarly disinclined to take other steps aimed at limiting the spread of the virus.

Gallup didn’t break out those groups by party, but it’s clear that few of them are Democrats. Data from YouGov, compiled on behalf of Yahoo News, shows that Democrats (and those who voted for Joe Biden in particular) are more likely to say that they have already received a vaccine dose.

Among those who hadn’t yet received a dose, Democrats were far more likely to indicate that they planned to do so as soon as possible. Among Republicans, half of those who haven’t been vaccinated say that they don’t have any plans to do so at all.

One reason is that Republicans are simply less worried about the virus. More than half say that they’re not very worried about it or not worried at all. Among those who voted for Donald Trump, the figure is over two-thirds. By contrast, more than three-quarters of Democrats say that they are at least somewhat worried about the virus.

In the YouGov polling, 60 percent of Republicans say that the worst of the pandemic is behind us. They’re also much more likely to say that restrictions aimed at preventing the spread of the virus — mask mandates, limits on indoor dining — should be lifted immediately.

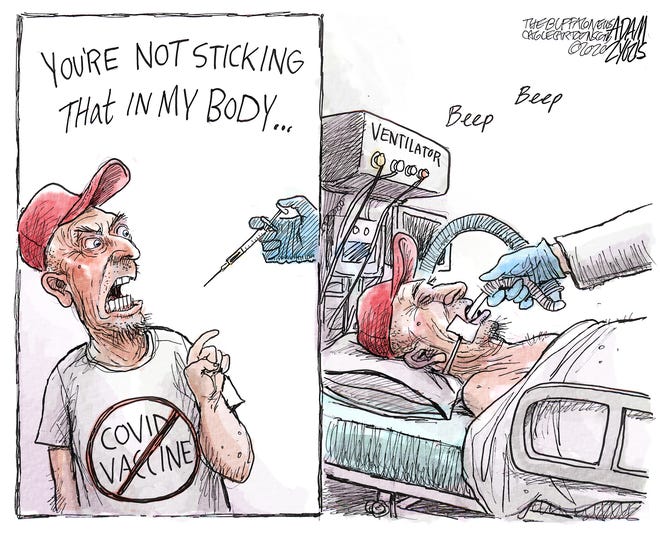

As we mentioned Thursday, there are two ways to achieve herd immunity. One is fast and safe: widespread vaccinations. The other — people contracting the virus — is slow and dangerous. The path the United States is on will take us to a place where much of the country has opted for the first option and the rest, the latter.

So the question again becomes: How many people will die, both over the short term and the long term, as a result of those choices?