Leadership Defined

Quote of the Day: On True Leadership

Medicare Advantage’s $64 Billion Supplemental Benefits Slush Fund

Medicare spends huge sums financing the dental, vision and other benefits offered by Medicare Advantage plans. A new government report sounds the alert about their potential misuse.

In mid-March, the Medicare Payments Advisory Commission (MedPAC), which advises Congress on Medicare policy, made a bombshell disclosure in its annual Medicare report. The rebates that Medicare offers Medicare Advantage plans for supplemental benefits like vision, dental, and gym membership were at “nearly record levels”, more than doubling from 2018 to nearly $64 billion in 2024, but the government “does not have reliable information about enrollees’ actual use of these benefits at this time.”

In other words: $64 billion is being spent to subsidize private Medicare Advantage plans to provide benefits that are not available to enrollees in traditional Medicare, and the government has no idea how they are being spent.

Not only is this an enormous potential misallocation of taxpayer resources from the Medicare trust fund, it is also a critical part of Medicare Advantage’s marketing scam. The additional benefits offered in Medicare Advantage plans are what entice people to give up traditional Medicare, where there is no prior authorization, closed networks, or care denials.

But, as MedPAC states in the report, even though the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) does not collect the data on utilization of supplemental benefits, what little data there is does not paint a pretty picture, with MedPAC noting that, “Limited data suggest that use of non-Medicare-covered supplemental benefits is low.”

HEALTH CARE un-covered is among the first media outlet to report MedPAC’s findings.

A 2018 study by Milliman, an actuarial firm, found that just 11 percent of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries had claims for dental care in that year, and that “multiple studies using survey data have found that beneficiaries with dental coverage in MA are not more likely to receive dental services than other Medicare beneficiaries.” A study from the Consumer Healthcare Products Association found that just one-third of eligible participants in Medicare Advantage plans used an over-the-counter medication benefit at pharmacies, leaving $5 billion annually on the table for insurers to pocket. Elevance Health, formerly Anthem, has 42 supplemental benefits available to Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. They analyzed a subset of 860,000 beneficiaries. For six of the 42 benefits, the $124 billion insurer could not report utilization data. For the other 36 supplemental benefits, the bulk of those covered used fewer than four benefits, with a full quarter not using any benefits at all and a majority using one or less benefits.

Medpac added that it had “previously reported that while these benefits often include coverage for vision, hearing, or dental services, the non-Medicare supplemental benefits are not necessarily tailored toward populations that have the greatest social or medical needs. The lack of information about enrollees’ use of supplemental benefits makes it difficult to determine whether the benefits improve beneficiaries’ health.”

With studies already showing that Medicare Advantage is associated with increased racial disparities in seniors’ health care, the massive subsidies provided to supplemental benefits appears to be an inadvertent driver of this problem:

the $64 billion—at least the portion of it that is actually being spent as opposed to deposited into insurer coffers—is likely not going to the populations that actually need it.

Amber Christ is the managing director of health policy for Justice in Aging, which advocates for the rights of seniors. “Health plans are receiving a large amount of dollars to provide supplemental benefits through rebates to plans. Clearly the offering have expanded, but the extent that they are being used is a black box,” she said. What little we do know, she said, indicates a “real lack of utilization.”

Christ pointed out that the Biden administration has taken some significant steps forward. “We’ve seen some good things coming out of CMS that will bring some transparency—the plans are going to have to report spending and utilization data, and in 2026 they will have to start sending notices to enrollees at the six-month point, letting people know what benefits they have used and what’s available. Those are all good moves.”

What’s missing from the proposed rule-making, however, is how the colossal outlays to supplemental benefits impact the goal of health equity, Christ said. “What we would have wanted to see more is demographics around utilization. Are there disparities in access?”

Of particular concern to advocates is the way that Medicare Advantage plans use supplemental benefits to market to “dual eligibles,” people who are eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans have taken to offering what amounts to cash benefits to dual eligibles, which provides a very strong incentive for people to sign up for Medicare Advantage.

But it’s effectively a trap, as being in both Medicare Advantage and Medicaid can not only result in prior authorization, care denials, and losing access to one’s physician, but also making care endlessly complex.

“Medicaid offers a bunch of supplemental benefits, either fully or often more comprehensively than Medicare Advantage. Seniors get lured into these health plans for benefits that they already have access to. But because benefits between Medicare Advantage and Medicaid aren’t coordinated people experience disruptions to their access to care. If they are dually enrolled it should go above and beyond, not duplicate coverage or making it more difficult to access coverage,” Christ said.

David Lipschutz, the associate director of the Center for Medicare Advocacy, related an experience he had with a state health official who counseled a senior against enrolling in Medicare Advantage. The official “was able to stop them and help them think through their choices. She wanted to enroll in a Medicare Advantage plan that offered a flex benefit,” which is basically restricted cash (Aetna, for example, restricts its recipients to spending the money at stores owned by CVS Health, its parent company). “None of her five doctors contracted with the Medicare Advantage plan. Had it not been with that interaction with the health counselor. She would have traded the flex card for no access to her current physicians. It’s an untenable situation.”

Lipschutz added that Medicare Advantage insurers contract with community organizations to administer supplemental benefits, which helps to insulate the industry from political pressure from advocates in Washington. “This whole new range of supplemental benefits has also at the same time pulled in a lot of community based organizations. They need the cash that the plans are offering. It creates a welcome dynamic for insurance companies trying to make community organizations dependent on their money. But it’s not a good situation to be in when you’re trying to reign in Medicare Advantage overpayments.”

Bid/Ask

The core of the financing of supplemental benefits is through a bid system, in which CMS sets a benchmark based on area fee-for-service Medicare spending, and then invites insurers to submit a bid, and then receives a rebate for supplemental benefits based on the benchmark. The essential problem is that the average person in traditional Medicare is sicker than someone in a Medicare Advantage plan—the research shows that when patients get sick, they leave Medicare Advantage for traditional Medicare if they can. And Medicare Advantage plans aggressively market to healthier patients—the oft-touted gym membership supplemental benefit only works for those who actually work out at the gym regularly. (Well under one-third of those 75 and over.)

And in counties with low traditional Medicare spending, the benchmark is at 115 or 107.5 percent—an unreasonable and massive subsidy written into the Affordable Care Act at the behest of the insurance lobby. The lowest benchmark is at 95 percent of FFS spending for areas with high costs.

“The way the payment is set up leads to this excessive amount of rebate dollars,” said Lipschutz. “It’s a fundamentally flawed payment system which is in dire need of reform.” Lipschutz’s position jives with the MedPAC report, which states that: “A major overhaul of MA policies is urgently needed.”

Supplements For Half

“You shouldn’t have to enroll in a private plan just to access these benefits,” said Lipschutz. But that’s exactly the choice millions of seniors are faced with. Forty-nine percent of seniors remain in traditional Medicare.

And for that group, Medicare offers no supplemental benefits, Christ said. “As a foundational principle spending all this money for Medicare Advantage to give supplemental benefits doesn’t make sense. This is the Medicare trust fund. Half of Medicare has “access,” and the other half, in traditional Medicare, doesn’t. Wouldn’t those dollars be better spent giving everyone access? Especially when we understand that Medicare Advantage has narrower providers and prior authorization.

There’s a recognition that these supplemental benefits have positive impacts on quality of life, but we’re not offering it in traditional Medicare—even though Medicare Advantage is not doing a better job than traditional Medicare.”

House of Cards?

A new lawsuit, filed in April, could substantially impact the incentives that plans have to offer supplemental benefits. To manage costs, many Medicare Advantage plans have value-based care arrangements with providers—meaning that they share some of their revenues with hospitals and other health providers to ensure access to networks and to smooth costs out in the long run.

But as part of this arrangement, providers bear some of the costs of the plans—including the cost of supplemental benefits. Bridges Health Partners, which is a clinically integrated network of doctors and hospitals, sued Aetna to block the allocation of supplemental benefits to the expenses that they bear the cost of, due to a 20-fold increase in their costs.

Combined with the 2026 requirement from CMS that participants be informed as to what benefits they haven’t used, insurers’ ability to offer these supplemental benefits and still retain sky-high profit margins could be curtailed.

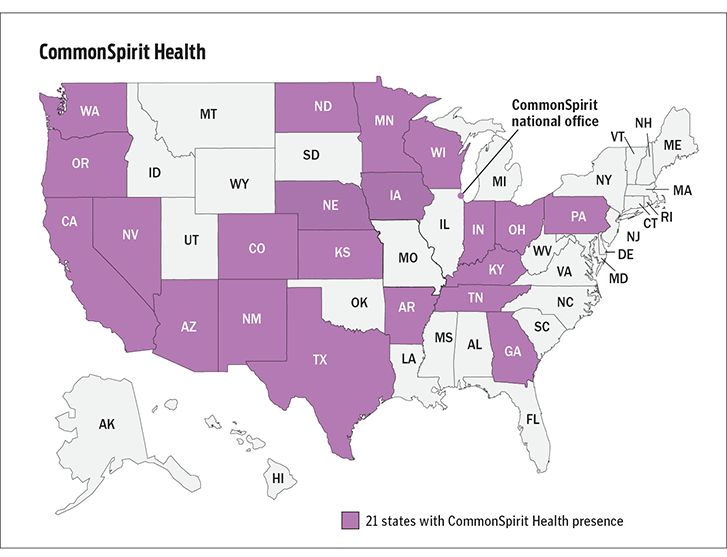

CommonSpirit ‘doubly concerned’ about California Medicaid

Chicago-based CommonSpirit is concerned about Medicaid funding across many of the states in which it operates, but “doubly concerned” about California, its strongest market and the state in which about 30% of its business occurs, CFO Dan Morissette said during a May 23 investor call.

Earlier this month, California Gov. Gavin Newsom outlined plans to divert more than $7 billion in funding from the healthcare sector to address a major funding deficit.

The governor’s proposal would reallocate $6.7 billion from Medi-Cal provider rate increases set for Jan. 1, 2025, to balance the state budget, which is facing a shortfall of $27.6 billion this year and a projected deficit of $28.4 billion in 2025.

“We’re doubly concerned given the state budget,” Mr. Morissette said. “Lean times create new concerns for us as it relates to Medicaid funding, which does not cover even the direct cost of care for the various ministries that we serve.”

California’s $6.7 billion funding proposal was generated by the managed care organization tax that was expected to provide $19.4 billion in federal funding through 2026. In 2024, rates rose to at least 87.5% of Medicare rates for primary care, maternity care and nonspecialty mental health providers. According to Politico, these rates will continue, but no more workers will be added under the revised plan.

CommonSpirit executives said that the health system is out of network with only one major payer in California — an unnamed Medicaid provider in the north of the state.

“All other payer arrangements have either just been signed or we were out of network for a short period of time and have successfully rejoined the network,” Mr. Morissette said. “We always find it disruptive — as all providers do — to be out of network, but sometimes we don’t have much choice given our need for the cross-subsidy where the commercial insurers do provide a substantial amount of our EBIDA margins. It’s a really difficult and delicate balance.”

CommonSpirit said it receives about $600 million in California provider fees — a permanent program through Proposition 52 — and these funds will not be affected because they are not part of the general fund.

“However, we always include a 0% increase in our budget and long-range financial planning when it comes to the Medicaid rate because that’s what we’ve been experiencing,” said Benjie Loanzon, senior vice president, finance and corporate controller. “We don’t expect an increase in the Medicaid rate with this proposal.”

Healthcare winners and losers after FTC bans non-compete clauses

With a single ruling, the Federal Trade Commission removed the nation’s occupational handcuffs, freeing almost all U.S. workers from non-compete clauses. The medical profession will never be the same.

On April 23, the FTC issued a final rule, affecting not only new hires but also the 30 million Americans currently tethered to non-compete agreements. Scheduled to take effect in September—subject to the outcome of legal challenges by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and other business groups—the ruling will dismantle longstanding barriers that have kept healthcare professionals from changing jobs.

The FTC projects that eliminating these clauses will boost medical wages, foster greater competition, stimulate job creation and reduce health expenditures by $74 billion to $194 billion over the next decade. This comes at a crucial moment for American healthcare, an industry in which 60% of physicians report burnout and 100 million people (41% of U.S. adults) are saddled with medical bills they cannot afford.

Like all major rulings, this one creates clear winners and losers—outcomes that will reshape careers and, potentially, alter the very structure of U.S. healthcare.

Winners: Newly Trained Clinicians

Undoubtedly, the FTC’s ruling is a win for younger doctors and nurses, many of whom join hospitals and health systems with the promise of future salary increases and more autonomy. However, by agreeing to stringent non-compete clauses, these newly trained clinicians have little choice but to place their trust in employers that, shielded by air-tight agreements, have no fear of breaking their promises.

Most newly trained clinicians enter the medical job market in their late 20s and early 30s, carrying significant student-loan debt—nearly $200,000 for the average doctor. Eager for stable, well-paying positions, these young professionals quickly settle into their careers and communities, forming strong relationships with friends and patients. Many start families.

But when these clinicians realize their jobs are falling short of the promises made early on, they face a tough decision: either endure subpar working conditions or uproot their lives. Taking a new job 25 or 50 miles away or moving to a different state are often are only options to avoid breaching a non-compete clause.

In a 570-page supplement to its ruling, the FTC published testimonials from dozens of healthcare professionals whose lives and careers were harmed by these clauses.

“Healthcare providers feel trapped in their current employment situation, leading to significant burnout that can shorten their career longevity,” said one physician working in rural Appalachia.

By banning non-competes, the FTC’s rule will boost career mobility for all clinicians within their own communities. This change will likely spur competition among employers—leading to improved pay and benefits to attract and, equally important, retain top talent. And with the reassurance that they can easily switch jobs if their current employer falls short of expectations, clinicians will enjoy greater professional satisfaction and less burnout.

Winners: Patients In Competitive Markets

Benefits that accrue to doctors and nurses from the FTC’s ban will translate directly to improved outcomes for patients. For example, we know that physicians who report symptoms of burnout are twice as likely to commit a serious medical error. Studies have shown the inverse is true, as well: healthcare providers who are satisfied with their jobs tend to have lower burnout rates, which is positively correlated with improved patient outcomes.

Once freed from restrictive non-compete clauses, many clinicians will practice elsewhere within the community. To attract patients, they will have to offer greater access, lower prices and more personalized service. Others with the freedom to choose will join outpatient centers that offer convenient and efficient alternatives for diagnostic tests, surgery and urgent medical care, often at a fraction of the cost of traditional hospital services. In both cases, increased competition will give patients improved medical care and added value.

Losers: Large Health Systems

Large health systems, which encompass several hospitals in a geographic area, have traditionally relied on non-compete agreements to maintain their market dominance. By barring high-demand medical professionals such as radiologists and anesthesiologists from joining competitors or starting independent practices, these systems have been able to suppress competition and force insurers to pay more for services.

Currently, these systems can demand high reimbursement rates from insurers while also maintaining relatively low wages for staff, creating a highly profitable model. Yale economist Zack Cooper’s research shows the consequence of the status quo: prices go up and quality declines in highly concentrated hospital markets.

The FTC’s ruling challenges those conditions, potentially dismantling monopolistic market controls. As a result, insurers will no longer be forced to contend with a single, dominant provider. And with health systems pushed to offer better wages and benefits to retain their top talent, bottom lines will shrink.

While nonprofit hospitals and health systems are not currently under the FTC’s jurisdiction, the agency has pointed out that these facilities might be at “a self-inflicted disadvantage in their ability to recruit workers.” Moreover, as Congress intensifies scrutiny on the nonprofit status of U.S. health systems, hospitals that do not voluntarily align with the FTC’s guidelines may find themselves compelled to do so through legislative actions.

Losers: Hospital Administrators

Individual hospitals have faced a unique challenge over the past decade. Across the country, inpatient numbers are falling, which makes it harder for hospital administrators to fill beds overnight. This trend has been driven by advancements in medical technology and new practices that enable more outpatient procedures, along with changes in insurance reimbursements favoring less costly outpatient care. As a result, hospital administrators have been compelled to adapt their financial strategies.

Nowadays, outpatient services account for about half of all hospital revenue. These range from physician consultations to specialized procedures like radiological and cardiac diagnostics, chemotherapy and surgeries.

Medicare and other insurers typically pay hospitals more for these outpatient services than they pay local doctors and other facilities. Knowing this, hospitals are hiring community doctors and acquiring diagnostic and procedural facilities, then boosting profitability by charging the higher hospital rates for the same services.

Hospital administrators know that this strategy only works if the newly hired clinicians are prohibited from quitting and returning to practice within the same community. If they do, their patients are likely to go with them. This is why the non-compete clauses are so essential to a hospital’s financial success.

As expected, the American Hospital Association opposes the FTC’s rule, arguing that non-compete clauses protect proprietary information. In practice, most of the doctors affected by the ban are providing standard medical care and have no proprietary knowledge that requires protection.

Looking Ahead

Today’s hospital systems are starkly divided between haves and have-nots. Facilities in affluent areas often enjoy high reimbursement rates from private insurers, boosting financial success and administrator salaries. In contrast, rural hospitals grapple with low patient volumes while facilities in economically disadvantaged, high-population areas face greater financial difficulties.

The current model is not working. The old ways of doing things—enforcing non-competes, charging higher fees for identical services and promoting market consolidation to hike prices—are not sustainable solutions.

The abolition of non-compete agreements will produce both winners and losers. In the healthcare sector, the ultimate measure of a policy’s impact should be its effect on patients—and the overwhelming evidence suggests that eliminating these clauses will benefit them greatly.

Steward Files for Bankruptcy and It Feels All Too Familiar

https://www.kaufmanhall.com/insights/blog/steward-files-bankruptcy-and-it-feels-all-too-familiar

Steward Health Care’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing on May 6, 2024, brought back bad memories of another large health system bankruptcy.

On July 21, 1998, Pittsburgh-based Allegheny Health and Education Research Foundation (AHERF) filed Chapter 11. AHERF grew very rapidly, acquiring hospitals, physicians, and medical schools in its vigorous pursuit of scale across Pennsylvania. Utilizing debt capacity and spending cash, AHERF quickly ran out of both, defaulted on its obligations, and then filed for bankruptcy. It was one of the largest bankruptcy filings in municipal finance and the largest in the rated not-for-profit hospital universe.

Steward Health Care is a for-profit, physician-owned hospital company, but its long-standing roots were in faith-based not-for-profit healthcare. Prior to the acquisition by Cerberus Capital Management in 2010, Caritas Christi Health Care System was comprised of six hospitals in eastern Massachusetts. Caritas was a well-regarded health system, providing a community alternative to the academic medical centers in downtown Boston. Over the next 14 years, Steward grew rapidly to 31 hospitals in eight states, most recently bolstered through an expansive sale-leaseback structure with a REIT. Per the bankruptcy filings, the company reported $9 billion in secured debt and leases on $6 billion of revenue.

Chapter 11 bankruptcy filings in corporate America are a means to efficiently sell assets or a path to re-emergence as a new streamlined company. A quick glance at Steward’s organizational structure shows a dizzying checkerboard of companies and LLCs that will require a massive untangling. Further, its capital structure includes both secured debt for operations and a separate and distinct lease structure for its facilities, and in bankruptcy, that signals significant complexity. Bankruptcy filings in not-for-profit healthcare are less common, although it is surprising that the industry did not see an increase after the pandemic. Not-for-profit hospitals that are in distress seem to hang on long enough to find a buyer, gain increased state funding, attain accommodations on obligations, or find some other escape route to avoid a payment default or filing.

Details regarding Steward’s undoing will unfold in the coming weeks as it moves through an auction process. But there are some early takeaways the not-for-profit industry can learn from this:

- Remain essential in your local market. Hospitals must prove their value to their constituents, including managed care payers, especially in competitive urban markets, as Steward may have learned in eastern Massachusetts and Miami. Prior strategies of making a margin as an out-of-network provider are no longer viable as patients must shoulder more of the financial burden. Simply put, your organization should be asking one question: does a managed care plan need our existing network to sell a product in our market? If the answer is no, you need to develop strategies that make your hospital essential.

- Embrace financial planning for long-term viability. Without it, a hospital or health system will be unable to afford the capital spending it needs to maintain attractive, patient-friendly, state-of-the art facilities or absorb long-term debt to fund the capital. Annual financial planning is more than just a trendline going forward. The scenarios and inputs must be well-founded, well-grounded in detail, and based on conservative assumptions. Increasing attention has to be paid to disrupters, innovators, specialized/segmented offerings, and expansion plans of existing and new competitors. Investors expect this from not-for-profit borrowers. Higher-performing hospitals and health systems of all sizes do this well.

- Build capital capacity through improved cash flow. It is undoubtedly clear that Steward, like AHERF, was unable to afford the capital and debt they thought they could, either through flawed financial planning of its future state or, more concerning, the complete absence of it. Or they believed that rapid growth would solve all problems, not detailed financial planning, the use of benchmarks, or a sharp focus on operations. Increasing that capacity through sustained financial performance will allow an organization to de-leverage and build capital capacity.

When the case studies are written about Steward, a fact pattern will be revealed that includes the inability or unwillingness to attain synergies as a system, underspending on facility capital needs given a severe liquidity crunch, labor challenges, and a rapid payer mix shift.

Underlying all of this will undoubtedly be a failure of governance and leadership as we saw with AHERF. It will also likely indicate that one of the most precious assets healthcare providers may have is the management bandwidth to ensure strategic plans are appropriately made, tested, monitored, and executed.

While Steward and AHERF may be held up as extreme cases, not-for-profit hospital governance must continue to focus on checks-and-balances of management resources. Likewise, management must utilize benchmarks, data, and strong financial planning, given the challenges the industry faces.

Walmart’s Primary Care Failure Is Important and a Problem

On August 8, 2014, Walmart announced it would expand on its existing five primary care centers to a total of 12 by the end of the year. These centers would offer more extensive services than those provided in Walmart walk-in clinics, including chronic disease management.

On September 13, 2019, Walmart announced it was opening the first expanded Walmart Health center, which would provide patients with primary care, laboratory, X-ray, EKG, counseling, dental, optical, and hearing services, with the “goal of becoming America’s neighborhood health destination.”

On April 30, 2024, Walmart announced it would close all 51 of its health centers in five states, as well as its virtual care services. “The challenging reimbursement environment and escalating operating costs create a lack of profitability that make the care business unsustainable for us at this time,” Walmart said.

Make no mistake, this announcement is a big deal.

Walmart is the largest retailer in the world, with about $650 billion in annual revenue, 10,500 stores in 19 countries, and 2.1 million employees—nearly 1.6 million in the U.S. alone. Healthcare services were an important corporate goal for Walmart, a goal the company pursued with significant financial investment and talented executives. Walmart’s healthcare strategy was carefully mapped out, with an expanding set of services tested in various formats and locations in Walmart’s formidable geographic and online presence.

Of course, one of Walmart’s goals was to create profit for the company through its foray into healthcare.

However, Walmart’s primary care strategy also held great promise for improving the health of the people Walmart serves, as well as reducing overall healthcare costs. A recent study by researchers at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and University of Chicago Medicine, focusing on more than 500,000 Medicare beneficiaries, found that regular primary care visits were associated with fewer risk-adjusted ED visits and hospitalizations, lower risk-adjusted expenditures, and greater cost savings. According to the study, results improved as the regularity and continuity of care increased, both of which potentially would have been facilitated by the highly accessible and affordable primary care that Walmart aimed to deliver.

These benefits to patients and communities would have been especially powerful in rural America. Walmart plays a central role in the rural ecosystem, both as an economic and a social center. Ninety percent of the population is located within 10 miles of a Walmart.

Four thousand of Walmart’s stores are located in HRSA-designated medically underserved areas. In a time when rural healthcare providers are struggling to remain viable and healthcare deserts are becoming more problematic, Walmart had a unique opportunity to be, as the company itself said, “the front door of healthcare for all Americans.”

That enormous opportunity to tackle one of the most significant and persistent problems in American healthcare has now been lost.

Walmart is a corporation with a great history, a great reputation, great resources, and great operational abilities. If any company could make primary care work effectively and efficiently on a large scale in this country, it should have been Walmart.

But, after nearly two decades of trying, Walmart couldn’t succeed as a healthcare provider.

We can draw at least three important conclusions from Walmart’s healthcare failure.

- Healthcare as a cash business is a very difficult business model. Like other retailers, Walmart focused on healthcare as a cash business, providing high-volume, low-price services that consumers would pay for largely out-of-pocket. Walmart’s healthcare failure strongly indicates that, even with Walmart’s U.S. footprint of 4,615 stores and 255 million weekly customers, the company could not generate the volume necessary at acceptable price points to make cash healthcare profitable.

- It is unbelievably hard to work around the fundamental reimbursement model of American healthcare. Unable to make healthcare as a cash business work, the company ran smack into America’s unfriendly reimbursement system as its source of revenue. For Walmart as for many other healthcare providers, the predominant payers were Medicare and Medicaid, which, as every hospital executive experiences every day, do not pay at rates sufficient to cover costs—not a workable situation for a profit-oriented company in a capitalistic economy.

- Even a behemoth like Walmart could not manage around the current healthcare expense-to-revenue problem. Walmart is a company with all the tools any company could ask for to drive down operating expenses. It has the potential for economies of scale other companies could only dream of. It has processes for logistical efficiency that are viewed world-wide as a model of excellence. Yet even Walmart was unable to solve that most basic of healthcare economic problems: expenses—including labor, supplies, and drugs—are rising faster than revenue. Relatively few healthcare providers are able to achieve a positive margin in this environment, and for those that do achieve a margin, it is usually razor thin.

Obviously, healthcare’s business fundamentals are hard, and now we can see they are hard not only on traditional healthcare providers but also hard on a $650 billion retail company. These business fundamentals are unlikely to change anytime soon.

Walmart’s primary care failure is not only a disappointment for Walmart, but also for the healthcare ecosystem at large. What Walmart was trying to do was important, and that was establish a comprehensive retail system of primary care. Although Walmart’s effort, at least for the moment, has not worked, this is unlikely to be the end of the line. Hospitals and health systems will continue to experiment, will continue to apply their unique visions, their considerable talents, and their enormous dedication to the goal of finding primary care solutions that work for their communities.

As the Walmart failure demonstrates, the challenge is incredibly difficult. But the game must not be over.

The Do’s and Don’ts of Navigating the Health System when you Need It: My First-Hand Experience

I fell down a flight of stairs at 4 a.m. last Wednesday.

It was totally my fault.

Since then, I have used hospital emergency departments in 2 states, a freestanding imaging center and a large orthopedic clinic and I’m just getting started. Six days in, I’m lucky to be alive but I still don’t know the extent of my injuries, my chances of playing golf again nor what I will end up spending on this ordeal. But nonetheless, it could have been worse. I’m alive.

Surprises in all aspects of life are never anticipated fully and always disruptive. This one, for me, is no exception. I am frustrated by my accident and uncomfortable with sudden dependence on others to help navigate my recovery.

But this is also a teachable moment., As I am navigating through this ordeal, I find myself reflecting on the system—how it works or doesn’t—based on what I am experiencing as a patient.

Here’s my top three observations thus far:

The patient experience is defined by the support team:

The heroes in every setting I’ve used are the clerks, technicians, nurses and support staff who’ve made the experiences tolerable and/or reassuring. Patients like me are scared. Emotional support is key: some of that is defined by standard operating procedures and checklists but, in other settings, it’s cultural. Genuineness, empathy and personal attention is easy to gauge when pain is a factor. By the time physicians are on the scene, reassurance or fear is already in play. Care teams include not just those who provide hands-on care, but the administrative clerks and processes that either heighten patient anxiety or lessen fear. The health and well-being of the entire workforce—not just those who deliver hands-on care—matters. And it’s easy to see distinctions between organizations that embrace that notion and those that don’t.

Navigation is no-man’s land:

The provider organizations I’ve used thus far have 3 different owners and 3 different EHR systems. Each offers written counsel about ‘patient responsibility’ and each provides a list of do’s and don’ts for each phase of the process. Sharing test results across the 3 provider organizations is near impossible and coordination of care management is problematic unless all parties agree and protocols facilitating sharing in place. Perhaps because it was a holiday weekend, perhaps because staffing levels were less than usual, or perhaps because the organizations are fierce competitors, navigating the system has been unusually difficult. Navigating the system in an emergency is essential to optimal outcomes: processes to facilitate patient navigation are not in place.

What’s clear is hospitals, clinics and imaging facilities on different EHR systems don’t exchange data willingly or proactively. And, at every step, getting approvals from insurers a major step in the processes of care.

Price transparency is a non-issue in emergency care:

The services I am receiving include some that are “shoppable” and many that aren’t. I have no idea what I will end up spending, my out-of-pocket obligations nor what’s to come. I know among the mandatory forms I signed in advance of treatment in all 3 sites were consent forms for treatment and my obligation for payment. But in an emergency, it’s moot: there’s no way to know what my costs will be or my out-of-pocket responsibility. So, the hospital and insurer price transparency rules (2021, 2022) might elevate awareness of price distinctions across settings of care but their potential to bend the cost curve is still suspect.

Patients, like me, have to fend for ourselves. I am a number. Last Wednesday, waiting 85 minutes to be seen was frightening and frustrating though comparatively fast. Duplicative testing, insurer approvals, work-shift transitions, bedside manners, team morale, and sterile care settings seem the norm more than exception.

So, for me, the practical takeaways thus far are these:

- Don’t have an accident on a holiday weekend.

- Don’t expect front desk and check-out personnel to engage or answer questions. They’re busy.

- Don’t expect to start or leave without paying something or agreeing you will.

- Don’t expect waiting areas and exam rooms to be warm or inviting.

- Do have great neighbors and family members who can help. For me, Joe, Jordan, Erin and Rhonda have been there.

The health system is complicated and relationships between its major players are tense. Not surprisingly and for many legitimate reasons, my experience, thus far, is the norm. We can do better.

Paul

P.S. As I have reflected on the event last week, I found myself recalling the numerous times I called on “my doctors” to help my navigation of the system. They include Charles Hawes (deceased), Ben Womack, Ben Heavrin, David Maron, David Schoenfeld and Blake Garside. And, in the same context, the huge respect I have for clinicians I’ve known through Vanderbilt and Ohio State like Steve Gabbe and Andy Spickard who personify the best the medical profession has to offer. Thanks gentlemen. What you do matters beyond diagnoses and treatments. Who you are speaks volumes about the heart and soul of this industry now struggling to re-discover its purpose.