The U.S. health care industry is approaching a critical inflection point, according to veteran health care strategist Paul Keckley. In a candid and thought-provoking keynote at the 2025 Healthcare Marketing & Physician Strategies Summit (HMPS) in Orlando, Keckley outlined the challenges and potential opportunities health care leaders must navigate in an era of unprecedented economic uncertainty, regulatory disruption, and consumer discontent.

Drawing on decades of policy experience and his signature candid style, Keckley delivered a sobering yet actionable assessment of where the industry stands and what lies ahead.

Paul Keckley, PhD, health care research and policy expert and managing editor of The Keckley Report

Health care now accounts for a staggering 28 percent of the federal budget, with Medicaid expenditures alone ranging from the low 20s to 34 percent of individual state budgets. Despite its fiscal significance, Keckley points out that health care remains “not really a system, but a collection of independent sectors that cohabit the economy.”

In the article that follows, Keckley warns of a reckoning for those who remain entrenched in legacy assumptions. On the flip side, he notes, “The future is going to be built by those who understand the consumer, embrace transparency, and adapt to the realities of a post-institutional world.”

A Fractured System in a Fractured Economy

Fragmentation complicates any effort to meaningfully address rising costs or care quality. It also heightens the stakes in a political climate marked by what Keckley termed “MAGA, DOGE, and MAHA” factions, shorthand for various ideological forces shaping health care policy under the Trump 2.0 administration.

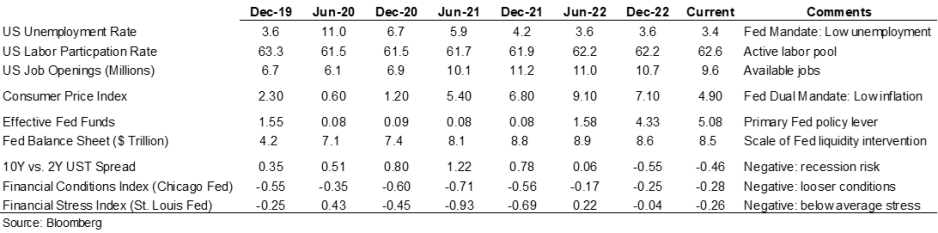

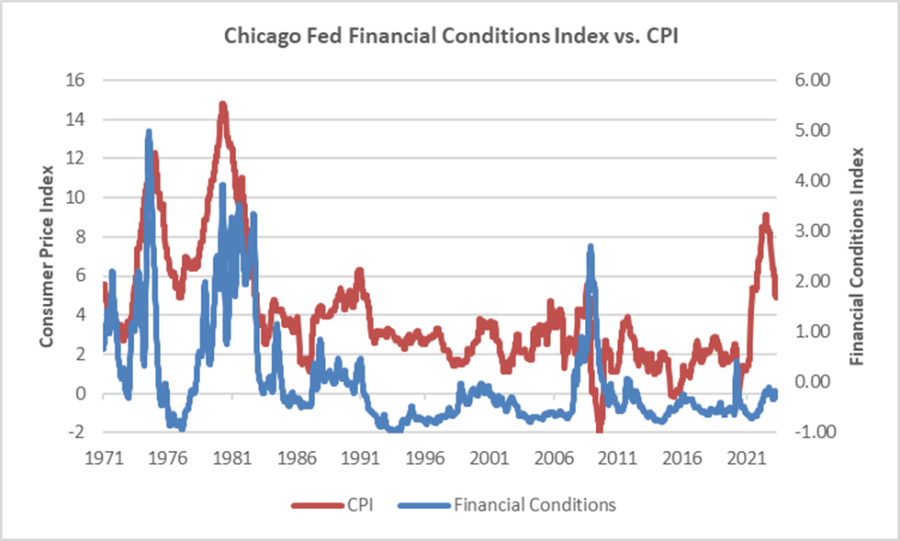

Meanwhile, macroeconomic conditions are only adding to the strain. At the time of Keckley’s address, the S&P 500 was down 8 percent, the Dow down 10 percent, and inflationary pressures were squeezing both provider margins and household budgets.

“Economic uncertainty is not just about Wall Street,” Keckley warns. “It’s about kitchen-table economics — how households decide between paying for care or paying the cable bill.”

Traditional Forecasting Is Failing

One of Keckley’s key messages was that conventional methods of strategic planning in health care, based on lagging indicators like utilization rates and demographics, are no longer sufficient. Instead, leaders must increasingly look to external forces such as capital markets, regulatory volatility, and consumer behavior.

“Think outside-in,” he urges. “Forces outside health care are shaping its future more than forces within.”

He encourages health systems to go beyond isolated market studies and adopt holistic scenario planning that considers clinical innovation, workforce shifts, AI and tech disruption, and capital availability as interconnected variables.

Affordability and Accountability: The Hospital Reckoning

Keckley pulls no punches in addressing the mounting criticism of hospitals on Capitol Hill, particularly not-for-profit health systems. Public perception is faltering, with hospital pricing increasing faster than other categories in health care and only a third of providers in full compliance with price transparency rules.

“Economic uncertainty is not just about Wall Street. It’s about kitchen-table economics — how households decide between paying for care or paying the cable bill.”

“We have to get honest about trust, transparency, and affordability,” he says. “I’ve been in 11 system strategy sessions this year. Only one even mentioned affordability on their website, and none defined it.”

Keckley also predicts that popular regulatory targets like site-neutral payments, the 340B program, and nonprofit tax exemptions will face intensified scrutiny.

“Hospitals are no longer viewed as sacred institutions,” he says. “They’re being seen as part of the problem, especially by younger, more educated, and more skeptical Americans.”

The Consumer Awakens

Perhaps the most urgent shift Keckley outlines is the redefinition of the health care consumer. “We call them patients,” he says, “but they are consumers. And they are not happy.”

Keckley cites polling data showing that two out of three Americans believe the health care system needs to be rebuilt from the ground up. Roughly 40 percent of U.S. households have at least one unpaid medical bill, with many choosing intentionally not to pay. Among Gen Y and younger households, dissatisfaction is particularly acute.

“[Consumers] expect digital, personalized, seamless experiences — and they don’t understand why health care can’t deliver.”

These consumers aren’t just passive recipients of care; they’re voters, payers, and critics. With 14 percent of health care spending now coming directly from households, Keckley argues, health systems must engage consumers with the same sophistication that retail and tech companies use.

“They expect digital, personalized, seamless experiences — and they don’t understand why health care can’t deliver.”

Tech Disruption Is Real

Keckley underscores the transformative potential of AI and emerging clinical technologies, noting that in the next five years, more than 60 GLP-1-like therapeutic innovations could come to market. But the deeper disruption, he warns, is likely to come from outside the traditional industry.

Citing his own son’s work at Microsoft, Keckley envisions a future where a consumer’s smartphone, not a provider or insurer, is the true hub of health information. “Health care data will be consumer-controlled. That’s where this is headed.”

The takeaway for providers: Embrace data interoperability and consumer-centric technology now, or risk irrelevance. “The Amazons and Apples of the world are not waiting for CMS to set the rules,” Keckley says.

Capital, Consolidation, and Private Equity

Capital constraints and the shifting role of private equity also featured prominently in Keckley’s remarks. With declining non-operating revenue and shrinking federal dollars, some health systems increasingly rely on investor-backed funding.

But this comes with reputational and operational risks. While PE investments have been beneficial to shareholders, Keckley says, they’ve also produced “some pretty dire results for consumers” — particularly in post-acute care and physician practice consolidation.

“Policymakers are watching,” he says. “Expect legislation that will limit or redefine what private equity can do in health care.”

Politics and Optics: Navigating the Policy Minefield

In the regulatory arena, Keckley emphasizes that perception often matters more than substance. “Optics matter often more than the policy itself,” he says.

He cautions health leaders not to expect sweeping policy reform but to brace for “de jure chaos” as the current administration focuses on symbolic populist moves — cutting executive compensation, promoting price transparency, and attacking nonprofit tax exemptions.

With the 2026 midterm elections looming large, Keckley predicts a wave of executive orders and rhetorical grandstanding. But substantive policy change will be incremental and unpredictable.

“Don’t wait for a rescue from Washington. The future is going to be built by those who understand the consumer, embrace transparency, and adapt to the realities of a post-institutional world.”

The Workforce Crisis That Wasn’t Solved

Keckley also addresses the persistent shortage of health care workers and the failure of Title V of the ACA, which had promised to modernize the workforce through new team-based models. “Our guilds didn’t want it,” Keckley notes, bluntly. “So nothing happened.”

He argues that states, not the federal government, will drive the next chapter of workforce reform, expanding the scope of practice for pharmacists, nurse practitioners, and even lay caregivers, particularly in behavioral health and primary care.

What Should Leaders Do Now?

Keckley closed his keynote with a challenge for marketers and strategists: Get serious about defining affordability, understand capital markets, and stop defaulting to legacy assumptions.

“Don’t wait for a rescue from Washington,” he says. “The future is going to be built by those who understand the consumer, embrace transparency, and adapt to the realities of a post-institutional world.”

He encouraged leaders to monitor shifting federal org charts, track state-level policy moves, and scenario-plan for a future where trust, access, and consumer empowerment define success.

Conclusion: A Health Care Reckoning in the Making

Keckley’s keynote was more than a policy forecast; it was a wake-up call. In a landscape shaped by economic headwinds, political volatility, and consumer rebellion, health care leaders can no longer afford to stay in their lane. They must engage, adapt, and transform, or risk becoming casualties of a system under siege.

“Health care is not just one of 11 big industries,” Keckley says. “It’s the one that touches everyone. And right now, no one is giving us a standing ovation.”