Cartoon – Specimens used for Covid-19 Testing and Experimentation

In the old days, pre-pandemic, the line in the brick-walled basement bar of Grendel’s Den would have consisted of young customers waiting to have their ID cards checked.

These days, says owner Kari Kuelzer, it’s made up of staff members getting checked for the coronavirus.

On a recent pre-opening early afternoon, a half dozen staffers assembled amid the twinkling lights and unoccupied tables, and Kuelzer handed out testing swabs.

“This is our test kit,” she explained, opening a clear plastic bag. “It’s a vial and then 10 swabs. They self-swab. And then it goes in the vial. And off I go to Kendall Square.”

Grendel’s Den, a classic Harvard Square hangout for more than 50 years, has just become the site of a coronavirus experiment: Twice a week, the restaurant will gather nose samples from up to 10 staffers, combine them and take them for processing to the company CIC Health a couple of miles away in Kendall Square.

Combining the samples is known as pooled testing — an increasingly popular way for employers, schools and others on limited budgets to keep an eye out for coronavirus infections. If the pool comes back negative, everyone’s good. If it’s positive, each person needs an individual test.

Kuelzer has been pushing the city of Cambridge and the broader restaurant community to get more testing,” to help us essentially achieve the sort of workplace safety that they achieved at Harvard University over the course of the fall,” she says.

Frequent testing helped Harvard and many other universities keep coronavirus rates low.

“If there’s people in our community in the university setting and at large institutions that are receiving that level of protection, there has to be a way to extend it to people who are not in that bubble of privilege, of being part of a major university,” Kuelzer says.

Until recently, she says, there wasn’t an affordable way to get her staff tested, and she had to ask them to do it on their own. In November, an outbreak hit seven staff members, and Grendel’s closed.

It recently reopened, and she found that testing had evolved to the point that she could get the staff pooled testing, twice a week, for $150 each time.

CIC Health already offers individual tests, and pooled testing to big institutions like schools, says chief marketing officer Rodrigo Martinez.

“And the other piece that is missing is exactly how do you offer pooled testing to a small company, restaurant, organization, team, nonprofit, whatever it is, in a way that they can actually access it?” he says. “And this is exactly the service that we’re piloting in beta.”

By “beta,” Martinez means that the Grendel’s Den arrangement is basically a field test to see how it goes and iron out kinks, and CIC Health isn’t marketing it broadly yet. But the market could be large.

“In theory, every small business that wants testing might be in need and desire of being able to do pooled testing,” he says.

The market could also be temporary. At Grendel’s, Kari Kuelzer says she sees the pooled testing as only a stopgap until the staff can get vaccinated.

It’s a stopgap that patrons can help support if they choose, in a brand new type of tipping: They can buy their server a coronavirus test for $15.

“If you want to help this waitress or that bartender who you care about because they make your day good stay safe, you can buy them a test,” Kuelzer says.

Overall, she says, it’s so far so good for the Grendel’s Den testing experiment. The result from the first round of testing came back last week in less than 24 hours — and it was negative for the coronavirus.

https://mailchi.mp/128c649c0cb4/the-weekly-gist-january-22-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

As one of his first official actions upon taking office Wednesday, President Biden signed an executive order implementing a federal mask mandate, requiring masks to be worn by all federal employees and on all federal properties, as well as on all forms of interstate transportation. Yesterday Biden followed that action by officially naming his COVID response team, and issuing a detailed national plan for dealing with the pandemic. Describing the plan as a “full-scale wartime effort”, Biden highlighted the key components of the plan in an appearance with Dr. Anthony Fauci and COVID response coordinator Jeffrey Zients.

The plan instructs federal agencies to invoke the Defense Production Act to ensure adequate supplies of critical equipment, including masks, testing equipment, and vaccine-related supplies; calls for new national guidelines to help employers make workplaces safe for workers to return to their jobs, and to make schools safe for students to return; and promises to fully fund the states’ mobilization of the National Guard to assist in the vaccine rollout.

Also included in the plan is a new Pandemic Testing Board, charged with ramping up multiple forms of COVID testing; more investment in data gathering and reporting on the impact of the pandemic; and the establishment of a health equity task force, to ensure that vulnerable populations are an area of priority in pandemic response.

But Biden can only do so much by executive order. Funding for much of his ambitious COVID plan will require quick legislative action by Congress, meaning that the administration will either need to garner bipartisan support for its proposed “American Rescue Plan” legislation, or use the Senate’s budget reconciliation process to pass the bill with a simple majority (with Vice President Harris casting the tie-breaking vote). Even that may prove challenging, given skepticism among Republican (and some moderate Democratic) senators about the $1.9T price tag for the legislation.

We’d anticipate intense bargaining over the relief package—with broad agreement over the approximately $415B in spending on direct COVID response, but more haggling over the size of the economic stimulus component, including the promised $1,400 per person in direct financial assistance, expanded unemployment insurance, and raising the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour.

Some of the broader economic measures, along with the rest of Biden’s healthcare agenda and his larger proposals to invest in rebuilding critical infrastructure, may have to wait for future legislation, as the administration prioritizes COVID relief as its first—and most important—order of business.

With bubble-enclosed Santas and Zoom-enhanced family gatherings, much of the United States played it safe over Christmas while the coronavirus rampaged across the country.

But a significant number of Americans traveled, and uncounted gatherings took place, as they will over the New Year holiday.

And that, according to the nation’s top infectious disease expert, Anthony S. Fauci, could mean new spikes in cases, on top of the existing surge.

“We very well might see a post-seasonal — in the sense of Christmas, New Year’s — surge,” Dr. Fauci said on CNN’s “State of the Union.”

“We’re really at a very critical point,” he said. “If you put more pressure on the system by what might be a post-seasonal surge because of the traveling and the likely congregating of people for, you know, the good warm purposes of being together for the holidays, it’s very tough for people to not do that.”

On “Fox News Sunday,” Adm. Brett P. Giroir, the administration’s testing coordinator, noted that Thanksgiving travel did not lead to an increase of cases in all places, which suggested that many people heeded recommendations to wear masks and limit the size of gatherings.

“It really depends on what the travelers do when they get where they’re going,” Admiral Giroir said. “We know the actual physical act of traveling in airplanes, for example, can be quite safe because of the air purification systems. What we really worry about is the mingling of different bubbles once you get to your destination.”

Still, U.S. case numbers are about as high as they have ever been. Total infections surpassed 19 million on Saturday, meaning that at least 1 in 17 people have contracted the virus over the course of the pandemic. And the virus has killed more than 332,000 people — one in every thousand in the country.

Two of the year’s worst days for deaths have been during the past week. A number of states set death records on Dec. 22 or Dec. 23, including Alabama, Wisconsin, Arizona and West Virginia, according to The Times’s data.

And hospitalizations are hovering at a pandemic height of about 120,000, according to the Covid Tracking Project.

Against that backdrop, millions of people in the United States have been traveling, though many fewer than usual.

About 3.8 million people passed through Transportation Safety Administration travel checkpoints between Dec. 23 and Dec. 26, compared with 9.5 million on those days last year. Only a quarter of the number who flew on the day after Christmas last year did so on Friday, and Christmas Eve travel was down by one-third from 2019.

And AAA’s forecast that more than 81 million Americans would travel by car for the holiday period, from Dec. 23 to Jan. 3, which would be about one-third fewer than last year.

For now, the U.S. is no longer seeing overall explosive growth, although California’s worsening outbreak has canceled out progress in other parts of the country. The state has added more than 300,000 cases in the seven-day period ending Dec. 22. And six Southern states have seen sustained case increases in the last week: Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, Florida and Texas.

Holiday reporting anomalies may obscure any post-Christmas spike until the second week of January. Testing was expected to decrease around Christmas and New Year’s, and many states said they would not report data on certain days.

On Christmas Day, numbers for new infections, 91,922, and deaths, 1,129, were significantly lower than the seven-day averages. But on Saturday, new infections jumped past 225,800 new cases and deaths rose past 1,640, an expected increase over Friday as some states reported numbers for two days post-Christmas.

Congressional leaders have reached an agreement on a $900 billion COVID-19 relief package and $1.4 trillion government funding deal with several healthcare provisions, according to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., and Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y.

Here are seven things to know about the relief aid and funding deal:

1. Congressional leaders have yet to release text of the COVID-19 legislation, but have shared a few key details on the measure, according to CNBC. Becker’s breaks down the information that has been released thus far.

2. The COVID-19 package includes $20 billion for the purchase of vaccines, about $9 billion for vaccine distribution and about $22 billion to help states with testing, tracing and other COVID-19 mitigation programs, according to Politico.

3. Lawmakers are also expected to include a provision changing how providers can use their relief grants. In particular, the bill is expected to allow hospitals to calculate lost revenue by comparing budgeted revenue for 2020. Hospitals have said this tweak will allow them to keep more funding.

4. The agreement also allocates $284 billion for a new round of Paycheck Protection Program loans.

5. The COVID-19 relief bill also provides $600 stimulus checks to Americans earning up to $75,000 per year and $600 for their children, according to NBC. It also provides a supplemental $300 per week in unemployment benefits.

6. The year-end spending bill includes a measure to ban surprise billing. Under the measure, hospitals and physicians would be banned from charging patients out-of-network costs their insurers would not cover. Instead, patients would only be required to pay their in-network cost-sharing amount when they see an out-of-network provider, according to The Hill. The agreement gives insurers 30 days to negotiate a payment on the outstanding bill. After that period, they can enter into arbitration to gain higher reimbursement.

7. Lawmakers plan to pass the relief bill and federal spending bill Dec. 21.

https://www.yahoo.com/news/covid-19-silently-spreading-across-193716206.html

The first confirmed coronavirus case in the U.S. was reported on Jan. 19 in a Washington man after returning from Wuhan, China, where the first outbreak of COVID-19 occurred.

Now, data from a new government study paints a different picture — the coronavirus may have been silently spreading in America as early as December 2019.

Researchers with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention collected 7,389 blood samples from routine donations to the American Red Cross between Dec. 13, 2019 and Jan. 17, 2020.

Of the samples, 106 contained coronavirus antibodies, suggesting those individuals’ immune systems battled COVID-19 at some point.

A total of 39 donations carrying coronavirus antibodies came from residents in the western states of California, Oregon and Washington and 67 samples from the more eastern states of Connecticut, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, Rhode Island and Wisconsin.

The study, published Monday in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, adds to growing evidence that the coronavirus had been spreading right under our noses long before testing could confirm it.

“The presence of these serum antibodies indicate that isolated SARS-CoV-2 infections may have occurred in the western portion of the United States earlier than previously recognized or that a small portion of the population may have pre-existing antibodies that bind SARS-CoV-2,” the study reads.

However, the researchers say “widespread community transmission was not likely until late February.”

Some of these early infections may have gone unnoticed because patients with mild or asymptomatic cases may not have sought medical care at the time, the researchers explain in the study. Sick patients with symptoms who did visit a doctor may not have had a respiratory sample collected, so appropriate testing may not have been conducted.

But the researchers wonder if the detection of antibodies in these patient samples really does indicate a past coronavirus infection, and not of another pathogen in the coronavirus family, such as the common cold.

A study published in August found that people who have had the common cold could have cells in their immune systems that might be able to recognize those of the novel coronavirus, McClatchy News reported.

Scientists behind the finding say this “memory” of viruses past could explain why some people are only slightly affected by COVID-19, while others get severely sick.

The researchers call this phenomenon “cross reactivity,” but they note it’s just one of several limitations to their study. The team also said they can’t tell if the COVID-19 cases were community- or travel-associated and that none of the antibody results can be considered “true positives.”

“A true positive would only be collected from an individual with a positive molecular diagnostic test,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Back in May, doctors in Paris also learned the coronavirus had been silently creeping around Europe a month before the official first-known cases were diagnosed in the region.

The first two cases — with known travel to China — in France were reported Jan. 24, but after testing frozen samples from earlier patient records, doctors realized a man with no recent travel had the coronavirus in December.

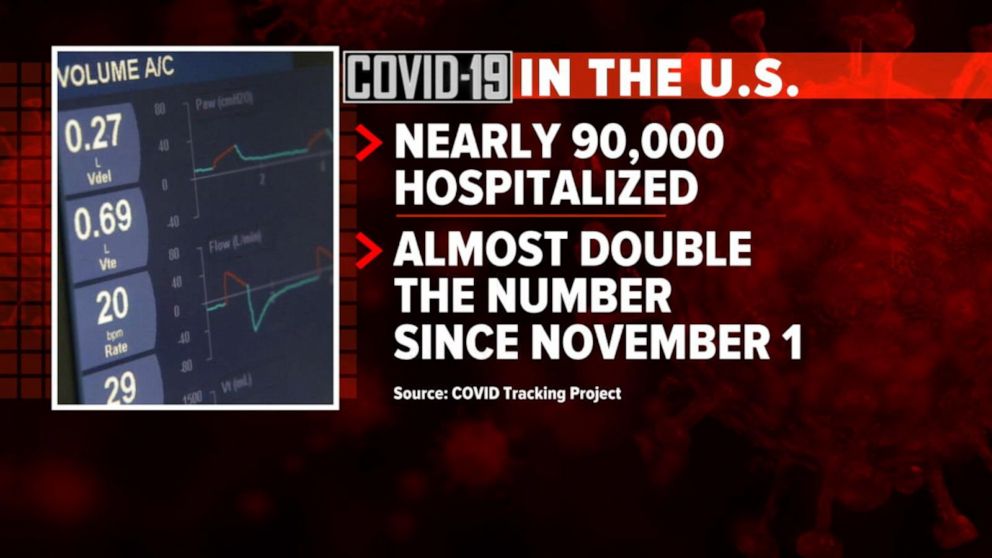

The United States recorded 90,481 people currently hospitalized with COVID-19 Nov. 26, marking the 17th consecutive day of record hospitalizations and the first time the daily count topped 90,000, according to The COVID Tracking Project.

The Project has noted that several data points will likely “wobble” over the next several days due to the Thanksgiving holiday, which may cause data points for COVID-19 testing, new cases and deaths to flatten or drop for several days before spiking. It is unlikely that Thanksgiving infections will be clearly visible in official case data until at least the second week of December.

However, the Project’s staff has noted that the new admissions metric in the public hospitalization dataset from HHS shows only moderate volatility and will likely be an additional source of useful data through the expected holiday dip and subsequent spike in test, case and death data.

“If you’re a reporter covering COVID-19, we recommend focusing on current hospitalizations and new admissions as the most reliable indicator of what is actually happening in your area and in the country as a whole,” reads the Nov. 24 blog from The COVID Tracking Project.

On her day off not long ago, emergency room nurse Jane Sandoval sat with her husband and watched her favorite NFL team, the San Francisco 49ers. She’s off every other Sunday, and even during the coronavirus pandemic, this is something of a ritual. Jane and Carlos watch, cheer, yell — just one couple’s method of escape.

“It makes people feel normal,” she says.

For Sandoval, though, it has become more and more difficult to enjoy as the season — and the pandemic — wears on. Early in the season, the 49ers’ Kyle Shanahan was one of five coaches fined for violating the league’s requirement that all sideline personnel wear face coverings. Jane noticed, even as coronavirus cases surged again in California and across the United States, that Levi’s Stadium was considering admitting fans to watch games.

But the hardest thing to ignore, Sandoval says, is that when it comes to coronavirus testing, this is a nation of haves and have-nots.

Among the haves are professional and college athletes, in particular those who play football. From Nov. 8 to 14, the NFL administered 43,148 tests to 7,856 players, coaches and employees. Major college football programs supply dozens of tests each day, an attempt — futile as it has been — to maintain health and prevent schedule interruptions. Major League Soccer administered nearly 5,000 tests last week, and Major League Baseball conducted some 170,000 tests during its truncated season.

Sandoval, meanwhile, is a 58-year-old front-line worker who regularly treats patients either suspected or confirmed to have been infected by the coronavirus. In eight months, she has never been tested. She says her employer, California Pacific Medical Center, refuses to provide testing for its medical staff even after possible exposure.

Watching sports, then, no longer represents an escape from reality for Sandoval. Instead, she says, it’s a signal of what the nation prioritizes.

“There’s an endless supply in the sports world,” she says of coronavirus tests. “You’re throwing your arms up. I like sports as much as the next person. But the disparity between who gets tested and who doesn’t, it doesn’t make any sense.”

This month, registered nurses gathered in Los Angeles to protest the fact that UCLA’s athletic department conducted 1,248 tests in a single week while health-care workers at UCLA hospitals were denied testing. Last week National Nurses United, the country’s largest nursing union, released the results of a survey of more than 15,000 members. About two-thirds reported they had never been tested.

Since August, when NFL training camps opened, the nation’s most popular and powerful sports league — one that generates more than $15 billion in annual revenue — has conducted roughly 645,000 coronavirus tests.

“These athletes and teams have a stockpile of covid testing, enough to test them at will,” says Michelle Gutierrez Vo, another registered nurse and sports fan in California. “And it’s painful to watch. It seemed like nobody else mattered or their lives are more important than ours.”

Months into the pandemic, and with vaccines nearing distribution, testing in the United States remains something of a luxury. Testing sites are crowded, and some patients still report waiting days for results. Sandoval said nurses who suspect they’ve been exposed are expected to seek out a testing site on their own, at their expense, and take unpaid time while they wait for results — in effect choosing between their paycheck and their health and potentially that of others.

“The current [presidential] administration did not focus on tests and instead focused on the vaccine,” says Mara Aspinall, a professor of biomedical diagnostics at Arizona State University. “We should have focused with the same kind of ‘warp speed’ on testing. Would we still have needed a vaccine? Yes, but we would’ve saved more lives in that process and given more confidence to people to go to work.”

After a four-month shutdown amid the pandemic’s opening wave, professional sports returned in July. More than just a contest on television, it was, in a most unusual year, a symbol of comfort and routine. But as the sports calendar has advanced and dramatic adjustments have been made, it has become nearly impossible to ignore how different everything looks, sounds and feels.

Stadiums are empty, or mostly empty, while some sports have bubbles and others just pretend their spheres are impermeable. Coaches stand on the sideline with fogged-up face shields; rosters and schedules are constantly reshuffled. On Saturday, the college football game between Clemson and Florida State was called off three hours before kickoff. Dodger Stadium, home of the World Series champions, is a massive testing site, with lines of cars snaking across the parking lot.

Sports, in other words, aren’t a distraction from a polarized nation and its response to a global pandemic. They have become a constant reminder of them. And when some nurses turn to sports for an attempt at escape, instead it’s just one more image of who gets priority for tests and, often, who does not.

“There is a disconnect when you watch sports now. It’s not the same. Covid changed everything,” says Gutierrez Vo, who works for Kaiser Permanente in Fremont, Calif. “I try not to think about it.”

Sandoval tries the same, telling herself that watching a game is among the few things that make it feel like February again. Back then, the coronavirus was a distant threat and the 49ers were in the Super Bowl.

That night, Sandoval had a shift in the ER, and between patients, she would duck into the break room or huddle next to a colleague checking the score on the phone. The 49ers were playing the Kansas City Chiefs, and Sandoval would recall that her favorite team blowing a double-digit lead represented the mightiest stress that day.

Now during shifts, Sandoval sometimes argues with patients who insist the virus that has infected them is a media-driven hoax. She masks up and wears a face shield even if a patient hasn’t been confirmed with the coronavirus, though she can’t help second-guessing herself.

“Did I wash my hands? Did I touch my glasses? Was I extra careful?” she says.

If Sandoval suspects she has been exposed, she says, she doesn’t bother requesting a test. She says the hospital will say there aren’t enough. So instead she self-monitors and loads up on vitamin C and zinc, hoping the tickle in her throat disappears. If symptoms persist, which she says hasn’t happened yet, she plans to locate a testing site on her own. But that would mean taking unpaid time, paying for costs out of pocket and staying home — and forfeiting a paycheck — until results arrive.

National Nurses United says some of its members are being told to report to work anyway as they wait for results that can take three to five days. Sutter Health, the hospital system that oversees California Pacific Medical Center, said in a statement to The Washington Post that it offers tests to employees whose exposure is deemed high-risk and to any employee experiencing symptoms. Symptomatic employees are placed on paid leave while awaiting test results, according to the statement.

“As long as an essential healthcare worker is asymptomatic,” Sutter’s statement read, “they can continue to work and self-monitor while awaiting the test result.”

Sandoval said employees have been told the hospital’s employee health division will contact anyone who has been exposed. Though she believes she’s exposed during every shift, Sandoval says employee health has never contacted her to offer a test or conduct contact tracing.

“If you feel like you need to get tested, you do that on your own,” she says. Sandoval suspects the imbalance is economic. In September, Forbes reported NFL team revenue was up 7 percent despite the pandemic. Last week Sutter Health reported a $607 million loss through the first nine months of 2020.

Sandoval tries to avoid thinking about that, so she keeps heading back to work and hoping for the best. Though she says her passion for sports is less intense now, she nonetheless likes to talk sports when a patient wears a team logo. She asks about a star player or a recent game. She says she is looking forward to the 49ers’ next contest and the 2021 baseball season.

Sometimes, Sandoval says, patients ask about her job and the ways she avoids contracting the coronavirus. She must be tested most every day, Sandoval says the patients always say.

And she just rolls her eyes and chuckles. That, she says, only happens if you’re an athlete.