In the Pandemic Era, Is It Safe to Go to Work?

A waiter wearing a face shield and mask to protect himself and others from the coronavirus serves diners at a restaurant in Santa Monica, California, on June 21, 2020. Photo: David Livingston / Getty Images

Stories that caught our attention.

In communities across the country, businesses that have been closed for months because of the new coronavirus are reopening their doors. In California’s Napa Valley, you can visit some wineries by appointment. In Idaho, you can sweat it out at a gym while maintaining distance from your workout partner. In New York City, not long ago the epicenter of the nation’s coronavirus crisis, you can once again get a haircut.

The reopening of these businesses means that some workers have returned to work in service jobs even as new cases of COVID-19 continue to surge. Others, deemed “essential” workers because of their industries, never stopped. Is it safe for frontline workers to continue in or return to their place of business? Do their workspaces have the basic health and safety measures in place to protect them from coronavirus transmission?

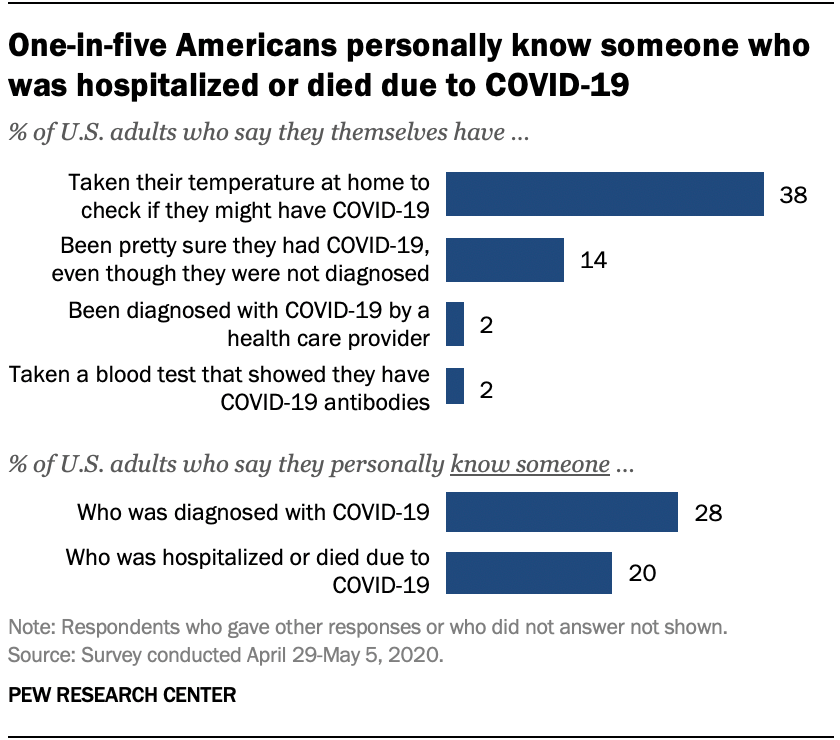

A recent analysis by KFF examined how many adult workers face an increased likelihood of severe illness if infected with the new coronavirus based on risk factors like being over age 65 or living with a chronic diseases like diabetes, moderate to severe asthma, and others. KFF found that more than 37 million American workers — nearly one in four — are at high risk of serious illness resulting from COVID-19.

It’s a scary thing to go back and know you have low immunity.

—Patti Hanks, Virginia furniture store worker

Twelve million adults who are not working live with those higher risks in households with at least one full-time worker, thereby exposing them indirectly to the infection risks of housemates doing customer-facing or other service jobs during a pandemic.

The ability to earn income from home is a privilege, and the “impossible choice between lives and livelihoods falls mainly to lower-wage workers in service industries,” KFF President and CEO Drew Altman wrote in Axios. Here’s what it’s like to work in four jobs that require face-to-face interaction during the worsening COVID-19 crisis.

Patti Hanks, Virginia

Soon after finishing chemotherapy for ovarian cancer, Patti Hanks had to go back to her job processing transactions at a furniture and appliance store in Virginia. She was nervous about returning to work during the pandemic, but she couldn’t afford to lose employer-sponsored health insurance.

“It’s a scary thing to go back and know you have low immunity,” Hanks, 62, told Sarah Kliff in the New York Times. “But when it all boils down to it, I don’t think COVID-19 is going away any time soon. I don’t think you can hide from it.”

Nearly 60% of Americans under 65 have employer health coverage, according to the Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. For people like Hanks, that makes work and health interdependent. Even without her furniture store job, she likely makes too much income from other sources (rental properties and raising cattle) to qualify for Medicaid.

So Hanks continues reporting to work. She wears a mask in the store, maintains distance from customers, and sanitizes shared objects like chairs and pens frequently. Still, there’s only so much she can control. The store has been busy since Virginia began lifting stay-at-home restrictions in May, and Hanks has assisted at least one customer who appeared to be unwell.

“You can’t crawl into a hole,” she told Kliff. “I think we’ve done everything we can to protect ourselves. . . . So I’ll just keep going.”

David Smith, Michigan

In normal times, David Smith, co-owner of the European-style eatery Café Muse in the Detroit suburb of Royal Oak, has one of his younger employees seat customers for dine-in service. But times are certainly not normal — nor are interactions with customers.

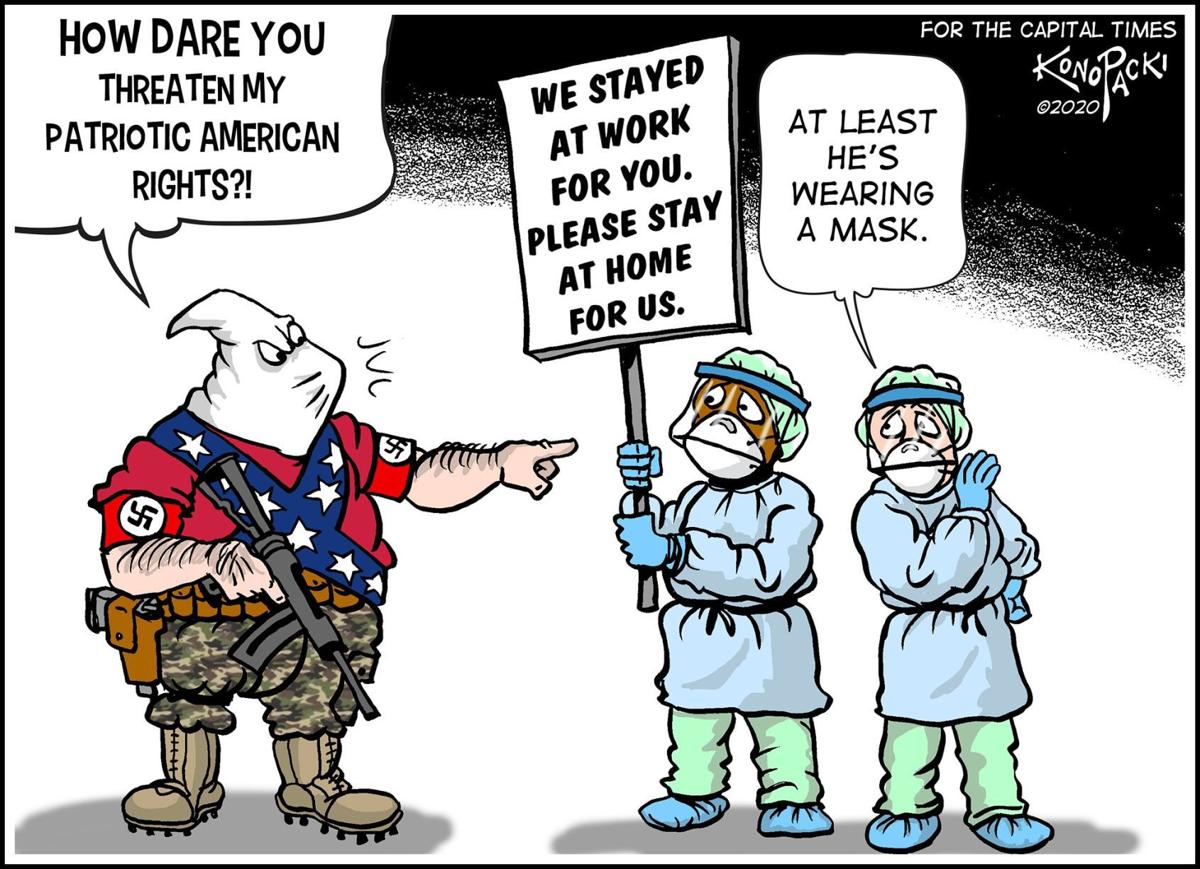

“I’ve been trying to do most of the seating, because it’s just really difficult when you have like an 18- or 19-year-old [employee] at the front having to enforce mask wearing,” he told Brenna Houck for her article in Eater Detroit.

The restaurant has been open for dine-in service for a only few weeks, and Smith has already had to call the police on an irate customer who refused to wear a mask when picking up a to-go order. Smith’s business partner, Greg Reyner, stepped in to ask the customer to wait for his food outside, and when the man refused, Reyner asked him to leave. The customer later called the restaurant and allegedly threatened the staff, leading Smith and Reyner to call the police.

The state of Michigan allowed restaurants and bars to reopen for indoor and outdoor dine-in service on June 8. Governor Gretchen Whitmer mandated that each customer must “wear a face covering over his or her nose and mouth . . . when in any enclosed public space, unless the individual is unable medically to tolerate a face covering.” Additionally, businesses are permitted to deny entry or access to anyone who refuses to comply with the mask rule.

That doesn’t mean it’s easy or pleasant to enforce the rule for the safety of staff and customers. “It is very upsetting,” Smith told Houck. “You’re shaking after having these conversations with people, because you just don’t know. What if someone got killed because they told [a customer] to wear a mask? You worry about it all the time.”

Amanda, Missouri

Nursing homes and assisted living facilities are hot spots for COVID-19 cases. Amanda (who asked that her last name be withheld) is a receptionist at a nursing home in St. Louis, and the last few months have been extremely stressful as she and her colleagues work to keep the facility free of COVID-19.

“I can’t sleep nowadays because I dream about being the cause of people dying,” she told Vox’s Luke Winkie. “That’s a horrifying thought for me. I’ve written up my resignation several times. But I don’t have the heart to do it because they need me there.”

So far, the nursing home has not had any cases, and Amanda attributes this to the facility’s early adoption of safety precautions. In February, the administrators advised staff to use personal protective equipment at work, regularly disinfect surfaces, and shelter in place at home when they weren’t working. The facility stopped admitting visitors, and when families dropped off presents for Mother’s Day, staff put the presents on hold for 24 to 72 hours before giving them to the residents.

[My family and I] never even hugged one another when I went to the emergency department because I don’t want to infect them.

—Marcial Reyes, emergency room nurse

Amanda and her colleagues take precautions not only at work, but also at home. “I won’t let my kids see their friends,” she told Winkie. “A lot of people are letting their kids see other kids, but I nipped that in the bud right away. My colleagues have done the same.”

As states reopen, Amanda is increasingly worried about the health of senior citizens like the ones she cares for. “I believe that our government hasn’t done anything,” she said. “Why don’t we have rapid testing in our facility right now? They should be in every hospital, every nursing home, and they should continue to produce them until they’re in schools and courthouses.”

Marcial Reyes, California

Fourteen years ago, Marcial Reyes emigrated from the Philippines to the US on a work visa to become a nurse. He’s been a US citizen for eight years. He was working as an emergency room nurse in Fontana, California, when the COVID-19 crisis struck, Josie Huang reported in LAist.

Reyes knew he was at high risk of contracting the coronavirus. When he started experiencing shortness of breath, he quarantined himself on the first floor of his house, away from his wife Rowena, who is also a nurse, and their five-year-old son. But the symptoms kept getting worse, and eventually he drove himself to the hospital — to the same emergency room where he usually cares for patients.

His health deteriorated so rapidly over the next few days that his doctors put him in a medically induced coma and hooked him up to a ventilator for 10 days. “[My family and I] never even hugged one another when I went to the emergency department because I don’t want to infect them,” he told Huang.

In California, nearly one in five registered nurses is of Filipino descent, according to a 2016 survey (PDF) by the California Board of Registered Nursing. California hospitals have recruited heavily from the Philippines for more than a century. Filipino nurses have stepped up to work in underserved areas and work on the front lines of health crises like the AIDS epidemic and COVID-19.

“It’s not uncommon for many Filipino families to produce multiple health care workers,” Huang wrote. The Reyes family is just one such example. Rowena Reyes and their son both also tested positive for COVID-19, though they recovered without hospitalization.

Marcial Reyes’ recovery will be much slower and more complicated. He needs to regain strength in his legs, and he still struggles with writing, Huang reported. Still, he is looking forward to the day when he can return to the emergency room as a nurse.