Category Archives: High Deductible Health Plans

How Do Democrats and Republicans Rate Healthcare for 2024?

It feels as though November 5, 2024 is far away, but for both Democrats and Republicans, the election is now. On the issue of healthcare, the two parties’ approaches differ sharply.

Think back to the behemoth effort by Republicans to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act six years ago, an effort that left them floundering for a replacement, basically empty-handed. Recall the 2022 midterms, when their candidates in 10 of the tightest House and Senate races uttered hardly a peep about healthcare.

That reticence stood in sharp contrast to Democrats who weren’t shy about reiterating their support for abortion rights, simultaneously trying hard to ensure that Americans understood and applauded healthcare tenets in the Inflation Reduction Act.

As The Hill noted in early August, sounds like the same thing is happening this time around as America barrels toward November 2024. The publication said it reached to 10 of the leading Republican candidates about their plans to reduce healthcare costs and make healthcare more affordable, and only one responded: Rep. Will Hurd (R-Texas).

Healthcare ‘A Very Big Problem’

Maybe the party thinks its supporters don’t care. But, a Pew Research poll from June showed 64% of us think healthcare affordability is a “very big problem,” superseded only by inflation. In that research, 73% of Democrats and 54% of Republicans thought so.

Chuck Coughlin, president and CEO of HighGround, an Arizona-based public affairs firm, told The Hill that the results aren’t surprising.

“If you’re a Republican, what are you going to talk about on healthcare?” he said.

Observers note that the party has homed in on COVID-lockdowns, transgender medical rights, and yes, abortion.

Republicans Champion CHOICE

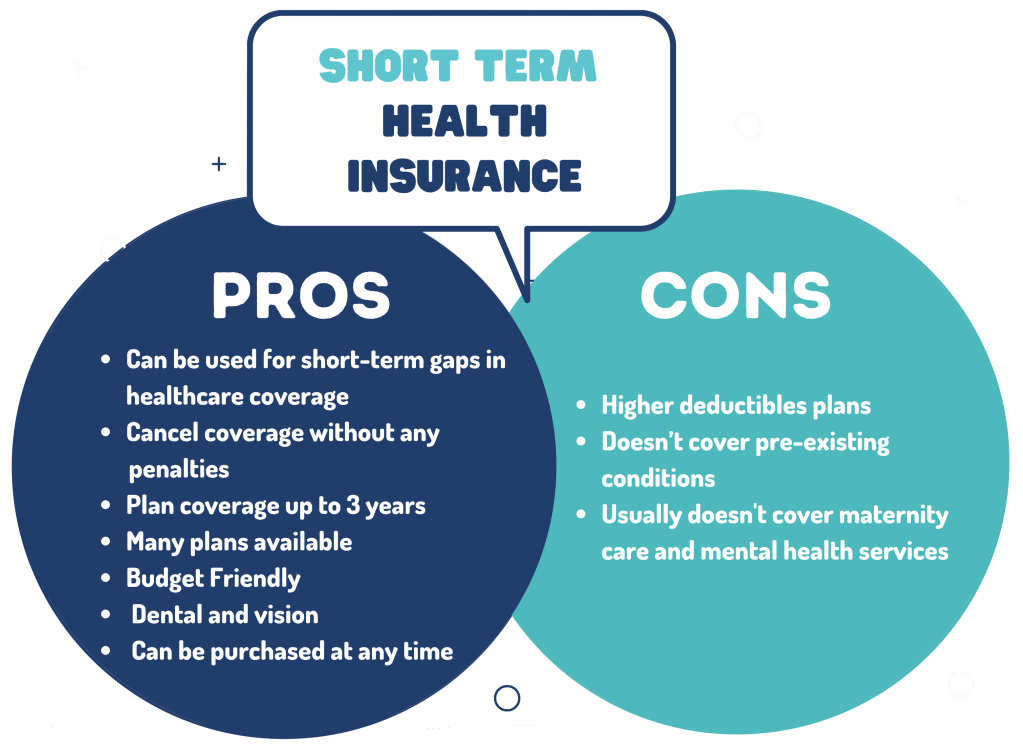

There is action on this front, for in late July, House Republicans passed the CHOICE Arrangement Act. Its future with the Democratic-controlled Senate is bleak, but if Republicans triumph in the Senate and White House next year, it could advance with its focus on short-term health plans. They don’t offer the same broad ACA benefits and have a troubling list of “what we won’t cover” that feels like coverage is going backwards to some.

Plans won’t offer coverage for preexisting conditions, maternity care, or prescription drugs, and they can set limits on coverage. The plans will make it easier for small employers to self-insure, so they don’t have to adhere to ACA or state insurance rules.

CHOICE would let large groups come together to buy Association Health Plans, said NPR, which noted that in the past, there have been “issues” with these types of plans.

Insurance experts say that the act takes a swing at the very foundation of the ACA. As one analyst described it, the act intends to improve America’s healthcare “through increased reliance on the free market and decreased reliance on the federal government.”

Democrats Tout Reduce-Price Prescriptions

Meanwhile, on Aug. 29, President Joe Biden spoke proudly in The White House: “Folks, there’s a lot of really great Republicans out there. And I mean that sincerely…But we’ll stand up to the MAGA Republicans who have been trying for years to get rid of the Affordable Care Act and deny tens of millions of Americans access to quality, affordable healthcare.”

Current ACA enrollment is higher than 16 million.

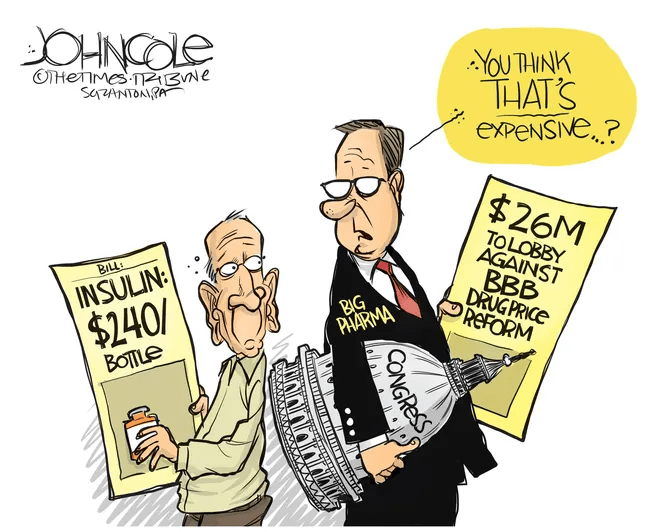

He said that Big Pharma charges Americans more than three times what other countries charge for medications. And on that date, he announced that “the (Inflation Reduction Act) law finally gave Medicare the power to negotiate lower prescription drug prices.” He wasn’t shy about saying that this happened without help from “the other team.”

The New York Times said it feels this push for lower healthcare costs will be the centerpiece of his re-election campaign. The announcement confirmed that his administration will negotiate to lower prices on 10 popular—and expensive drugs—that treat common chronic illnesses.

It said previous research shows that as many as 80% of Americans want the government to have the power to negotiate.

The president also said that “Next year, Medicare will select more drugs for negotiation.” He added that his administration “is cracking down on junk health insurance plans that look like they’re inexpensive but too often stick consumers with big hidden fees.” And it’s tackling the extensive problem of surprise medical bills.

Earlier, on August 11, Biden and fellow Democrats celebrated the first anniversary of the PACT Act, legislation that provides healthcare to veterans exposed to toxic burn pits while serving. He said more than 300,000 veterans and families have received these services, with more than 4 million screened for toxic exposure conditions.

Push for High-Deductible Plans

Republicans want to reduce risk of high-deductible plans and make them more desirable—that responsibility is on insurers. According to Politico, these plans count more than 60 million people as members, and feature low premiums and tax advantages. The party said plans will also help lower inflation when people think twice about seeking unneeded care.

The plans’ low monthly premiums offer comprehensive preventive care coverage: physicals, vaccinations, mammograms, and colonoscopies, and have no co-payments, Politico said. The “but” in all this is that members will pay their insurers’ negotiated rate when they’re sick, and for medicines and surgeries. Minimum deductible is $1,500 or $3,000 for families—and can be even higher.

Members can fund health savings accounts but can’t fund flexible spending accounts.

Proponents cite more access to care, and reduced costs due to promotion of preventive care. Nay-sayers worry about lower-income members facing costly bills due to insufficient coverage.

Republican Candidates Diverge on Medicaid

The American Hospital Association (AHA) doesn’t love these high deductible plans. It explained that members “find they can’t manage the gap between what their insurance pays and what they themselves owe as a result,” and that, AHA said, contributes to medical debt—something the association wants to change.

An Aug. 3 Opinion in JAMA Health Forum pointed out other ways the two parties diverge on healthcare. For example, the piece cited Biden’s incentives for Medicaid expansion. In contrast, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, a Republican presidential candidate, has not worked to offer Medicaid to all lower-income residents under the ACA. Former Governor Nikki Haley of South Carolina feels the same, doing nothing. However, former New Jersey Governor Chris Christie has expanded it, as did former Vice President Mike Pence, when he governed Indiana.

Undoubtedly, as in presidential elections past, healthcare will be at least a talking point, with Democrats likely continuing to make it a central focus, as before.

Sign of the Times: High Deductible Health Care

The Medicare Drug Pricing Program will Attract Uncomfortable Attention to the Rest of the Industry

Last Tuesday, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced the first 10 medicines that will be subject to price negotiations with Medicare starting in 2026 per authorization in the Inflation Reduction Act (2022). It’s a big deal but far from a done deal.

Here are the 10:

- Eliquis, for preventing strokes and blood clots, from Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer

- Jardiance, for Type 2 diabetes and heart failure, from Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly

- Xarelto, for preventing strokes and blood clots, from Johnson & Johnson

- Januvia, for Type 2 diabetes, from Merck

- Farxiga, for chronic kidney disease, from AstraZeneca

- Entresto, for heart failure, from Novartis

- Enbrel, for arthritis and other autoimmune conditions, from Amgen

- Imbruvica, for blood cancers, from AbbVie and Johnson & Johnson

- Stelara, for Crohn’s disease, from Johnson & Johnson

- Fiasp and NovoLog insulin products, for diabetes, from Novo Nordisk

Notably, they include products from 10 of the biggest drug manufacturers that operate in the U.S. including 4 headquartered here (Johnson and Johnson, Merck, Lilly, Amgen) and the list covers a wide range of medical conditions that benefit from daily medications.

But only one cancer medicine was included (Johnson & Johnson and AbbVie’s Imbruvica for lymphoma) leaving cancer drugs alongside therapeutics for weight loss, Crohn’s and others to prepare for listing in 2027 or later.

And CMS included long-acting insulins in the inaugural list naming six products manufactured by the Danish pharmaceutical giant Novo Nordisk while leaving the competing products made by J&J and others off. So, there were surprises.

To date, 8 lawsuits have been filed against the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services by drug manufacturers and the likelihood litigation will end up in the Supreme Court is high.

These cases are being brought because drug manufacturers believe government-imposed price controls are illegal. The arguments will be closely watched because they hit at a more fundamental question:

what’s the role of the federal government in making healthcare in the U.S. more affordable to more people?

Every major sector in healthcare– hospitals, health insurers, medical device manufacturers, physician organizations, information technology companies, consultancies, advisors et al may be impacted as the $4.6 trillion industry is scrutinized more closely . All depend on its regulatory complexity to keep prices high, outsiders out and growth predictable. The pharmaceutical industry just happens to be its most visible.

The Pharmaceutical Industry

The facts are these:

- 66% of American’s take one or more prescriptions: There were 4.73 billion prescriptions dispensed in the U.S. in 2022

- Americans spent $633.5 billion on their medicines in 2022 and will spend $605-$635 billion in 2025.

- This year (2023), the U.S. pharmaceutical market will account for 43.7% of the global pharmaceutical market and more than 70% of the industry’s profits.

- 41% of Americans say they have a fair amount or a great deal of trust in pharmaceutical companies to look out for their best interests and 83% favor allowing Medicare to negotiate pricing directly with drug manufacturers (the same as Veteran’s Health does).

- There were 1,106 COVID-19 vaccines and drugs in development as of March 18, 2023.

- The U.S. industry employs 811,000 directly and 3.2 million indirectly including the 325,000 pharmacists who earn an average of $129,000/year and 447,000 pharm techs who earn $38,000.

- And, in the U.S., drug companies spent $100 billion last year for R&D.

It’s a big, high-profile industry that claims 7 of the Top 10 highest paid CEOs in healthcare in its ranks, a persistent presence in social media and paid advertising for its brands and inexplicably strong influence in politics and physician treatment decisions.

The industry is not well liked by consumers, regulators and trading partners but uses every legal lever including patents, couponing, PBM distortion, pay-to-delay tactics, biosimilar roadblocks et al to protect its shareholders’ interests. And it has been effective for its members and advisors.

My take:

It’s easy to pile-on to criticism of the industry’s opaque pricing, lack of operational transparency, inadequate capture of drug efficacy and effectiveness data and impotent punishment against its bad actors and their enablers.

It’s clear U.S. pharma consumers fund the majority of the global industry’s profits while the rest of the world benefits.

And it’s obvious U.S. consumers think it appropriate for the federal government to step in. The tricky part is not just government-imposed price controls for a handful of drugs; it’s how far the federal government should play in other sectors prone to neglect of affordability and equitable access.

There will be lessons learned as this Inflation Reduction Act program is enacted alongside others in the bill– insulin price caps at $35/month per covered prescription, access to adult vaccines without cost-sharing, a yearly cap ($2,000 in 2025) on out-of-pocket prescription drug costs in Medicare and expansion of the low-income subsidy program under Medicare Part D to 150% of the federal poverty level starting in 2024. And since implementation of these price caps isn’t until 2026, plenty of time for all parties to negotiate, spin and adapt.

But the bigger impact of this program will be in other sectors where pricing is opaque, the public’s suspicious and valid and reliable data is readily available to challenge widely-accepted but flawed assertions about quality, value, access and outcomes. It’s highly likely hospitals will be next.

Stay tuned.

State Protections Against Medical Debt: A Look at Policies Across the U.S.

Abstract

- Issue: Medical debt negatively affects many Americans, especially people of color, women, and low-income families. Federal and state governments have set some standards to protect patients from medical debt.

- Goal: To evaluate the current landscape of medical debt protections at the federal and state levels and identify where they fall short.

- Methods: Analysis of federal and state laws, as well as discussions with state experts in medical debt law and policy. We focus on laws and regulations governing hospitals and debt collectors.

- Key Findings and Conclusion: Federal medical debt protection standards are vague and rarely enforced. Patient protections at the state level help address key gaps in federal protections. Twenty states have their own financial assistance standards, and 27 have community benefit standards. However, the strength of these standards varies widely. Relatively few states regulate billing and collections practices or limit the legal remedies available to creditors. Only five states have reporting requirements that are robust enough to identify noncompliance with state law and trends of discriminatory practices. Future patient protections could improve access to financial assistance, ensure that nonprofit hospitals are earning their tax exemption, and limit aggressive billing and collections practices.

Introduction

Medical debt, or personal debt incurred from unpaid medical bills, is a leading cause of bankruptcy in the United States. As many as 40 percent of U.S. adults, or about 100 million people, are currently in debt because of medical or dental bills. This debt can take many forms, including:

- past-due payments directly owed to a health care provider

- ongoing payment plans

- money owed to a bank or collections agency that has been assigned or sold the medical debt

- credit card debt from medical bills

- money borrowed from family or friends to pay for medical bills.

This report discusses findings from our review of federal and state laws that regulate hospitals and debt collectors to protect patients from medical debt and its negative consequences. First, we briefly discuss the impact and causes of medical debt. Then, we present federal medical debt protections and discuss gaps in standards as well as enforcement. Then, we provide an overview of what states are doing to:

- strengthen requirements for financial assistance and community benefits

- regulate hospitals’ and debt collectors’ billing and collections activities

- limit home liens, foreclosures, and wage garnishment

- develop reporting systems to ensure all hospitals are adhering to standards and not disproportionately targeting people of color and low-income communities.

(See the appendix for an overview of medical debt protections in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.)

Impact of Medical Debt

More than half of people in medical and dental debt owe less than $2,500, but because most Americans cannot cover even minor emergency expenses, this debt disrupts their lives in serious ways. Fear of incurring medical debt also deters many Americans from seeking medical care. About 60 percent of adults who have incurred medical debt say they have had to cut back on basic necessities like food or clothing, and more than half the adults from low-income households (less than $40,000) report that they have used up their savings to pay for their medical debt.

A significant amount of medical debt is either sold or assigned to third-party debt-collecting agencies, who often engage in aggressive efforts to collect on the debt, creating stress for patients. Both hospitals and debt collectors have won judgments against patients, allowing them to take money directly from a patient’s paycheck or place liens on a patient’s home. In some cases, patients have also lost their homes. Medical debt can also have a negative impact on a patient’s credit score.

Key Terms Related to Medical Debt

- Financial assistance policy: A hospital’s policy to provide free or discounted care to certain eligible patients. Eligibility for financial assistance can depend on income, insurance status, and/or residency status. A hospital may be required by law to have a financial assistance policy, or it may choose to implement one voluntarily. Financial assistance is frequently referred to as “charity care.”

- Bad debt: Patient bills that a hospital has tried to collect on and failed. Typically, hospitals are not supposed to pursue collections for bills that qualify for financial assistance or charity care, so bad debt refers to debt owed by patients ineligible for financial assistance.

- Community benefit requirements: Nonprofit hospitals are required by federal law and some state laws to provide community benefits, such as financial assistance and other investments targeting community need, in exchange for a tax exemption.

- Debt collectors or collections agencies: Entities whose business model primarily relies on collecting unpaid debt. They can either collect on behalf of a hospital (while the hospital still technically holds the debt) or buy the debt from a hospital.

- Sale of medical debt: Hospitals sometimes sell the debt patients owe them to third-party debt buyers, who can be aggressive in seeking repayment of the debt.

- Creditor: A party that is owed the medical debt and often wants to collect on the medical debt. This can be a hospital, a debt collector acting on behalf of a hospital, or a third-party debt buyer.

- Debtor: A patient who owes medical debt over unpaid medical bills.

- Wage garnishment: The ability of a creditor to get a court order that would allow them to deduct a portion of a debtor-patient’s paycheck before it reaches the patient. Federal law limits how much can be withheld from a debtor’s paycheck, and some states exceed this federal protection.

- Placing a lien: A legal claim that a creditor can place on a patient’s home, prohibiting the patient from selling, transferring, or refinancing their home without first paying off the creditor. Most states require creditors to get a court order before placing a lien on a home.

- Foreclosure or forced sale: A creditor can repossess and sell a patient’s home to pay off their medical debt. Often, creditors are required to obtain a court order to do so.

Perhaps what is most troubling is that the burden of medical debt is not borne equally: Black and Hispanic/Latino adults and women are much more likely to incur medical debt. Black adults also tend to be sued more often as a result. Uninsured patients, those from low-income households, adults with disabilities, and young families with children are all at a heightened risk of being saddled with medical debt.

Causes of Medical Debt

Most people — 72 percent, according to one estimate — attribute their medical debt to bills from acute care, such as a single hospital stay or treatment for an accident. Nearly 30 percent of adults who owe medical debt owe it entirely for hospital bills.

Although uninsured patients are more likely to owe medical debt than insured patients, having insurance does not fully shield patients from medical debt and all its consequences. More than 40 percent of insured adults report incurring medical debt, likely because they either had a gap in their coverage or were enrolled in insurance with inadequate coverage. High deductibles and cost sharing can leave many exposed to unexpected medical expenses.

The problem of medical debt is further exacerbated by hospitals charging increasingly high prices for medical care and failing to provide adequate financial assistance to uninsured and underinsured patients with low income.

Key Findings

Federal Medical Debt Protections Have Many Gaps

At the federal level, the tax code, enforced by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), requires nonprofit hospitals to broadly address medical debt. However, these requirements do not extend to for-profit hospitals (which make up about a quarter of U.S. hospitals) and have other limitations.

Further, the IRS does not have a strong track record of enforcing these requirements. In the past 10 years, the IRS has not revoked any hospital’s nonprofit status for noncompliance with these standards.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Federal Trade Commission have additional oversight authority over credit reporting and debt collectors. The Fair Credit Reporting Act regulates credit reporting agencies and those that provide information to them (debt collectors and hospitals). Consumers have the right to dispute any incomplete or inaccurate information and remove any outdated, negative information. In some cases, patients can directly sue hospitals or debt collectors for inaccurately reporting medical debt to credit reporting agencies. In addition, the Federal Debt Collection Practices Act limits how aggressive debt collectors can be by restricting the ways and times in which they can contact debtors, requiring certain disclosures and notifications, and prohibiting unfair or deceptive practices. Patients can directly sue debt collectors in violation of the law. This law, however, does not limit or prohibit the use of certain legal remedies, like wage garnishment or foreclosure, to collect on a debt.

Many states have taken steps to fill the gaps in federal standards. Within a state, several agencies may play a role in enforcing medical debt protections. Generally speaking:

- state departments of health are the primary regulators of hospitals and set standards for them

- state departments of taxation are responsible for ensuring nonprofit hospitals are earning their exemption from state taxes

- state attorneys general protect consumers from unfair and deceptive business practices by hospitals and debt collectors.

Fewer Than Half of States Exceed Federal Requirements for Financial Assistance, Protections Vary Widely

Federal law requires nonprofit hospitals to establish and publicize a written financial assistance policy, but these standards leave out for-profit hospitals and lack any minimum eligibility requirements. As the primary regulators of hospitals, states have the ability to fill these gaps and require hospitals to provide financial assistance to low-income residents. Twenty states require hospitals to provide financial assistance and set certain minimum standards that exceed the federal standard.

All but three of these 20 states extend their financial assistance requirements to for-profit hospitals. Of these 20 states, four states — Connecticut, Georgia, Nevada, and New York — apply their financial assistance requirements only to certain types of hospitals.

Policies also vary among the 31 states that do not have statutory or regulatory financial assistance requirements for hospitals. For example, the Minnesota attorney general has an agreement in place with nearly every hospital in the state to adhere to certain patient protections, though it falls short of requiring hospitals to provide financial assistance. Massachusetts operates a state-run financial assistance program partly funded through hospital assessments. Other states use far less prescriptive mechanisms to try to ensure that patients have access to financial assistance, such as placing the onus of treating low-income patients on individual counties or requiring hospitals to have a plan for treating low-income and/or uninsured patients without setting any specific requirements.

Enforcement of state financial assistance standards.

The only way to enforce the federal financial assistance requirement is to threaten a hospital’s nonprofit status, and the IRS has been reluctant to use this authority. Among the 20 states that have their own state financial assistance standards, 10 require compliance as a condition of licensure or as a legal mandate. These mandates are often coupled with administrative penalties, but some states have established additional consequences. For example, Maine allows patients to sue noncompliant hospitals.

Six states make compliance with their financial assistance standards a condition of receiving funding from the state. Two other states use their certificate-of-need process (which requires hospitals to seek the state’s approval before establishing new facilities or expanding an existing facility’s services) to impose their financial assistance mandates.

Setting eligibility requirements for financial assistance.

The federal financial assistance standard sets no minimum eligibility requirements for hospitals to follow. However, the 20 states with financial assistance standards define which residents are eligible for aid.

One way for states to ensure that financial assistance is available to those most in need is to prevent hospitals from discriminating against undocumented immigrants. Four states explicitly prohibit such discrimination in statute and regulation. Most states, however, are less explicit. Thirteen states define eligibility broadly, basing it most frequently on income, insurance status, and state residency. However, it is unclear how hospitals are interpreting this requirement when it comes to patients’ immigration status. In contrast, three states explicitly exclude undocumented immigrants from eligibility.

States also vary widely in terms of which income brackets are eligible for financial assistance and how much financial assistance they may receive.

At least three of the 20 states with financial assistance standards allow certain patients with heavy out-of-pocket medical expenses from catastrophic illness or prior medical debt to access financial assistance. Many states also require hospitals to consider a patient’s insurance status when making financial assistance determinations. At least six states make financial assistance available for uninsured patients only, while at least eight others also make financial assistance available to underinsured patients.

Standardizing the application process.

Cumbersome applications can discourage many patients from applying for financial assistance. Five states have developed a uniform application form, while three others have set minimum standards for financial assistance applications. Eleven states require hospitals to give patients the right to appeal a denial of financial assistance.

States Split in Requiring Nonprofit Hospitals to Invest in Community Benefits

Federal and state policymakers also can require nonprofit hospitals to invest in community benefits in return for tax exemptions. Federal law requires nonprofit hospitals to produce a community health needs assessment every three years and have an implementation strategy. Almost all states exempt nonprofit hospitals from a host of state taxes, including income, property, and/or sales taxes. However, only 27 impose community benefit requirements on nonprofit hospitals.

Community benefits frequently include financial assistance but also investments that address issues like lack of access to food and housing. In the long run, these investments can reduce medical debt burden by improving population health and the financial stability of a community. Most states that require nonprofit hospitals to provide community benefits allow nonprofit hospitals to choose how they invest their community benefit dollars. This hands-off approach has given rise to concerns about the lack of transparency in community benefit spending as well as questions about whether hospitals are investing this money in ways that are most helpful to the community, such as in providing financial assistance.

Applicability of community benefit standards.

Nineteen states impose community benefit requirements on all nonprofit hospitals in the state, but three states further limit these requirements to hospitals of a certain size. At least six states have extended these requirements to for-profit hospitals as well. Of these six, the District of Columbia, South Carolina, and Virginia have incorporated community benefit requirements into their certificate-of-need laws instead of their tax laws. As a result, any hospital seeking to expand in these states becomes subject to their community benefit requirement.

Interaction between financial assistance and community benefits.

The federal standard allows nonprofit hospitals to report financial assistance as part of their community benefit spending. Most states with community benefit requirements also allow hospitals to do this. However, only seven states require hospitals to provide financial assistance to satisfy their community benefit obligations.

Setting quantitative standards for community benefit spending.

Only seven states set minimum spending thresholds that hospitals must meet or exceed to satisfy state community benefit standards. For example, Illinois and Utah require nonprofit hospitals’ community benefit contributions to equal what their property tax liability would have been. Unique among states, Pennsylvania gives taxing districts the right to sue nonprofit hospitals for not holding up their end of the bargain, which has proven to be a strong enforcement mechanism.

Fewer Than Half the States Exceed Federal Standards for Billing and Collections

Hospital billing and collections practices can significantly increase the burden of medical debt on patients. However, the current federal standard does not regulate these practices beyond imposing waiting periods and prior notification requirements for certain extraordinary collections actions (ECAs), such as garnishing wages or selling the debt to a third party.

Requiring hospitals to provide payment plans.

Federal standards do not require hospitals to make payment plans available. However, a few states do require hospitals to offer payment plans, particularly for low-income and/or uninsured patients. For example, Colorado requires hospitals to provide a payment plan and limit monthly payments to 4 percent of a patient’s monthly gross income and to discharge the debt once the patient has made 36 payments.

Limiting interest on medical debt.

Federal law does not limit the amount of interest that can be charged on medical debt. However, eight states have laws prohibiting or limiting interest for medical debt. Some states like Arizona have set a ceiling for interest on all medical debt. Others like Connecticut further prohibit charging interest to patients who are at or below 250 percent of the federal poverty level and are ineligible for public insurance programs.

Though many states do not have specific laws prohibiting or limiting interest that hospitals or debt collectors can charge on medical debt, all states do have usury laws, which limit the amount of interest than can be charged on any oral or written agreement. Usury limits are set state-by-state and can range anywhere from 5 percent to more than 20 percent, but most limits fall well below the average interest rate for a credit card (around 24%). At least one state, Minnesota, has sued a health system for charging interest rates on medical debt that exceeded the allowed limit in the state’s usury laws.

Interactions between hospitals, third-party debt collectors, and patients.

Unlike hospitals, debt collectors do not have a relationship with patients and can be more aggressive when collecting on the debt. Federal law neither limits when a hospital can send a bill to collections, nor does it require hospitals to oversee the debt collectors it uses. Most states (37) also do not regulate when a hospital can send a bill to collections, although some states have developed more protective approaches.

For example, Connecticut prohibits hospitals from sending the bills of certain low-income patients to collections, and Illinois requires hospitals to offer a reasonable payment plan first. Additionally, five states require hospitals to oversee their debt collectors.

Sale of medical debt to third-party debt buyers.

Hospitals sometimes sell old unpaid debt to third-party debt buyers for pennies on the dollar. Debt buyers can be aggressive in their efforts to collect, and sometimes even try to collect on debt that was never owed. Federal law considers the sale of medical debt an ECA and requires nonprofit hospitals to follow certain notice and waiting requirements before initiating the sale. Most states (44) do not exceed this federal standard.

Only three states prohibit the sale of medical debt. Two other states — California and Colorado — regulate debt buyers instead. For example, California prohibits debt buyers from charging interest or fees, and Colorado prohibits them from foreclosing on a patient’s home.

Reporting medical debt to credit reporting agencies.

Federal law considers reporting medical debt to a credit reporting agency to be an ECA and requires nonprofit hospitals to follow certain notice and waiting requirements beforehand. Most states (41) do not exceed this federal standard.

Of the 10 states that do go beyond the federal standard, a few like Minnesota fully prohibit hospitals from reporting medical debt. Most others require hospitals, debt collectors, and/or debt buyers to wait a certain amount of time before reporting the debt to credit agencies (Exhibit 8). Two states directly regulate credit agencies: Colorado prohibits them from reporting on any medical debt under $726,200, while Maine requires them to wait at least 180 days from the date of first delinquency before reporting that debt.

States Vary Widely on Patient Protections from Medical Debt Lawsuits

Federal law considers initiating legal action to collect on unpaid medical bills to be an extraordinary collections action and also limits how much of a debtor’s paycheck can be garnished to pay a debt.

In most states, hospitals and debt buyers can sue patients to collect on unpaid medical bills. Three states limit when hospitals and/or collections agencies can initiate legal action. Illinois prohibits lawsuits against uninsured patients who demonstrate an inability to pay. Minnesota prohibits hospitals from giving “blanket approval” to collections agencies to pursue legal action, and Idaho prohibits the initiation of lawsuits until 90 days after the insurer adjudicates the claim, all appeals are exhausted, and the patient receives notice of the outstanding balance.

Liens and foreclosures.

Most states (32) do not limit hospitals, collections agencies, or debt buyers from placing a lien or foreclosing on a patient’s home to recover on unpaid medical bills. However, almost all states provide a homestead exemption, which protects some equity in a debtor’s home from being seized by creditors during bankruptcy. The amount of homestead exemption available to debtors varies from state to state, ranging from just $5,000 to the entire value of the home. Seven states have unlimited homestead exemptions, allowing debtors to fully shield their primary homes from creditors during bankruptcy. Additionally, Louisiana offers an unlimited homestead exemption for certain uninsured, low-income patients with at least $10,000 in medical bills.

Ten states prohibit or set limits on liens or foreclosures for medical debt. For example, New York and Maryland fully prohibit both liens and foreclosures because of medical debt, while California and New Mexico only prohibit them for certain low-income populations.

Wage garnishment.

Under federal law, the amount of wages garnished weekly may not exceed the lesser of: 25 percent of the employee’s disposable earnings, or the amount by which an employee’s disposable earnings are greater than 30 times the federal minimum wage. Twenty-one states exceed the federal ceiling for wage garnishment. Only a few states go further to prohibit wage garnishment for all or some patients. For example, New York fully prohibits wage garnishment to recover on medical debt for all patients, yet California only extends this protection for certain low-income populations. While New Hampshire does not prohibit wage garnishment, it requires the creditor to keep going back to court every pay period to garnish wages, which significantly limits creditors’ ability to garnish wages in practice.

Many States Have Hospital Reporting Requirements, But Few Are Robust

Federal law requires all nonprofit hospitals to submit an annual tax form including total dollar amounts spent on financial assistance and written off as bad debt. However, these reporting requirements do not extend to for-profit hospitals and lack granularity. States, as the primary regulators of hospitals, would likely benefit from more robust data collection processes to better understand the impact of medical debt and guide their oversight and enforcement efforts.

Currently, 32 states collect some of the following:

- financial data, including the total dollar amounts spent on financial assistance and/or bad debt

- financial assistance program data, including the numbers of applications received, approved, denied, and appealed

- demographic data on the populations most affected by medical debt

- information on the number of lawsuits and types of judgments sought by hospitals against patients.

Fifteen states explicitly require hospitals to report total dollar amounts spent on financial assistance and/or bad debt, while 11 states also require hospitals to report certain data related to their financial assistance programs. Most of these 11 states limit the data they collect to the numbers of applications received, approved, denied, and appealed. However, a handful of them go further and ask hospitals to report on the amount of financial assistance provided per patient, number of financial assistance applicants approved and denied by zip code, number of payment plans created and completed, and number of accounts sent to collections.

Five states require hospitals to further break down their financial assistance data by race, ethnicity, gender, and/or preferred or primary language. For example, Maryland requires hospitals to break down the following data by race, ethnicity, and gender: the bills hospitals write off as bad debt and the number of patients against whom the hospital or the debt collector has filed a lawsuit.

Only Oregon asks hospitals to report on the number of patient accounts they refer for collections and extraordinary collections actions.

Discussion and Policy Implications

In 2022, the federal government announced administrative measures targeting the medical debt problem, which included launching a study of hospital billing practices and prohibiting federal government lenders from considering medical debt when making decisions on loan and mortgage applications. Although these measures will help some, only federal legislation and enhanced oversight will likely address current gaps in federal standards.

States can also fill the gaps in federal patient protections by improving access to financial assistance, ensuring that nonprofit hospitals are earning their tax exemption, and protecting patients against aggressive billing and collections practices. States also can leverage underutilized usury laws to protect their residents from medical debt.

Finding the most effective ways to enforce these standards at the state level could also protect patients. Absent oversight and enforcement, patients from underserved communities continue to face harm from medical debt, even when states require hospitals to provide financial assistance and prohibit them from engaging in aggressive collections practices. Bolstering reporting requirements alone would not likely ensure compliance, but states could protect patients by strengthening their penalties, providing patients with the right to sue noncompliant hospitals, and devoting funding to increase oversight by state agency officials.

To develop a comprehensive medical debt protection framework, states could also bring together state agencies like their departments of health, insurance, and taxation, as well as their state attorney general’s office. Creating an interagency office dedicated to medical debt protection would allow for greater efficiency and help the state build expertise to take on the well-resourced debt collection and hospital industries.

Still, these measures only address the symptoms of the bigger problem: the unaffordability of health care in the United States. Federal and state policymakers who want to have a meaningful impact on the medical debt problem could consider the protections discussed in this report as part of a broader plan to reduce health care costs and improve coverage.

Not for Profit Hospitals: Are they the Problem?

Last Monday, four U.S. Senators took aim at the tax exemption enjoyed by not-for-profit (NFP) hospitals in a letter to the IRS demanding detailed accounting for community benefits and increased agency oversight of NFP hospitals that fall short.

Last Tuesday, the Elevance Health Policy Institute released a study concluding that the consolidation of hospitals into multi-hospital systems (for-profit/not-for-profit) results in higher prices without commensurate improvement in patient care quality. “

Friday, Kaiser Health News Editor in Chief Elizabeth Rosenthal took aim at Ballad Health which operates in TN and VA “…which has generously contributed to performing arts and athletic centers as well as school bands. But…skimped on health care — closing intensive care units and reducing the number of nurses per ward — and demanded higher prices from insurers and patients.”

And also last week, the Pharmaceuticals’ Manufacturers Association released its annual study of hospital mark-ups for the top 20 prescription drugs used on hospitals asserting a direct connection between hospital mark-ups (which ranged from 234% to 724%) and increasing medical debt hitting households.

(Excerpts from these are included in the “Quotables” section that follows).

It was not a good week for hospitals, especially not-for-profit hospitals.

In reality, the storm cloud that has gathered over not-for-profit health hospitals in recent months has been buoyed in large measure by well-funded critiques by Arnold Ventures, Lown Institute, West Health, Patient Rights Advocate and others. Providence, Ascension, Bon Secours and now Ballad have been criticized for inadequate community benefits, excessive CEO compensation, aggressive patient debt collection policies and price gauging attributed to hospital consolidation.

This cloud has drawn attention from lawmakers: in NC, the State Treasurer Dale Folwell has called out the state’s 8 major NFP systems for inadequate community benefit and excess CEO compensation.

In Indiana, State Senator Travis Holdman is accusing the state’s NFP hospitals of “hoarding cash” and threatening that “if not-for-profit hospitals aren’t willing to use their tax-exempt status for the benefit of our communities, public policy on this matter can always be changed.” And now an influential quartet of U.S. Senators is pledging action to complement with anti-hospital consolidation efforts in the FTC leveraging its a team of 40 hospital deal investigators.

In response last week, the American Hospital Association called out health insurer consolidation as a major contributor to high prices and,

in a US News and World Report Op Ed August 8, challenged that “Health insurance should be a bridge to medical care, not a barrier.

Yet too many commercial health insurance policies often delay, disrupt and deny medically necessary care to patients,” noting that consumer medical debt is directly linked to insurer’ benefits that increase consumer exposure to out of pocket costs.

My take:

It’s clear that not-for-profit hospitals pose a unique target for detractors: they operate more than half of all U.S. hospitals and directly employ more than a third of U.S. physicians.

But ownership status (private not-for-profit, for-profit investor owned or government-owned) per se seems to matter less than the availability of facilities and services when they’re needed.

And the public’s opinion about the business of running hospitals is relatively uninformed beyond their anecdotal use experiences that shape their perceptions. Thus, claims by not-for-profit hospital officials that their finances are teetering on insolvency fall on deaf ears, especially in communities where cranes hover above their patient towers and their brands are ubiquitous.

Demand for hospital services is increasing and shifting, wage and supply costs (including prescription drugs) are soaring, and resources are limited for most.

The size, scale and CEO compensation for the biggest not-for-profit health systems pale in comparison to their counterparts in health insurance and prescription drug manufacturing or even the biggest investor-owned health system, HCA…but that’s not the point.

NFPs are being challenged to demonstrate they merit the tax-exempt treatment they enjoy unlike their investor-owned and public hospital competitors and that’s been a moving target.

In 2009, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) updated the Form 990 Schedule H to require more detailed reporting of community benefit expenditures across seven different categories including charity care, unreimbursed costs from means-tested government programs, community health spending, research, and others. The Affordable Care Act added requirements that non-profit hospitals complete community health needs assessments (CHNAs) every three years to identify the most pressing community health priorities and create detailed implementation strategies explaining how the identified needs will be addressed.

Thus, the methodology for consistently defining and accounting for community benefits needs attention. That would be a good start but alone it will not solve the more fundamental issue: what’s the future for the U.S. health system, what role do players including hospitals and others need to play, and how should it be structured and funded?

The issues facing the U.S. health industry are complex. The role hospitals will play is also uncertain. If, as polls indicate, the majority of Americans prefer a private health system that features competition, transparency, affordability and equitable access, the remedy will require input from every major healthcare sector including employers, public health, private capital and regulators alongside others.

It will require less from DC policy wonks and sanctimonious talking heads and more from frontline efforts and privately-backed innovators in communities, companies and in not-for-profit health systems that take community benefit seriously.

No sector owns the franchise for certainty about the future of U.S. healthcare nor its moral high ground. That includes not-for-profit hospitals.

The darkening cloud that hovers over not-for-profit health systems needs attention, but not alone, despite efforts to suggest otherwise.

Clarifying the community-benefit standard is a start, but not enough.

Are NFP hospitals a problem? Some are, most aren’t but all are impacted by the darkening cloud.

Payers declare War on Corporate Hospitals: Context is Key

Last week, six notable associations representing health insurers and large employers announced Better Solutions for Healthcare (BSH): “An advocacy organization dedicated to bringing together employers, consumers, and taxpayers to educate lawmakers on the rising cost of healthcare and provide ideas on how we can work together to find better solutions that lower healthcare costs for ALL Americans.”

BSH, which represents 492 large employers, 34 Blue Cross plans, 139 insurers and 42 business coalitions, blames hospitals asserting that “over the last ten years alone, the cost of providing employee coverage has increased 47% with hospitals serving as the number one driver of healthcare costs.”

Its members, AHIP, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, the Business Group on Health, Public Sector Health Care Roundtable, National Alliance of Healthcare Purchaser Coalitions and the American Benefits Council, pledge to…

- Promote hospital competition

- Enforce Federal Price Transparency Laws for Hospital Charges

- Rein in Hospital Price Mark-ups

- Insure Honest Billing Practices

And, of particular significance, BSH calls out “the growing practice of corporate hospitals establishing local monopolies and leveraging their market dominance to charge patients more…With hospital consolidation driving down competition, there’s no pressure for hospitals to bring costs back within reach for employees, retirees and their families…prices at monopoly hospitals are 12% higher than in markets with four or more competitors.”

The BSH leadership team is led by DC-based healthcare policy veterans with notable lobbying chops: Adam “Buck” Buckalew, a former Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-TN) staffer who worked on the Health Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) committee and is credited with successfully spearheading the No Surprises Act legislation that took effect in January 2022, and Kathryn Spangler, another former HELP staffer under former Sen. Mike Enzi (R-WY) who most recently served as Senior Policy Advisor at the American Benefits Council.

It’s a line in the sand for hospitals, especially large not-for-profit systems that are on the defensive due to mounting criticism.

Examples from last week: Atrium and Caremont were singled in NC by the state Treasurer for their debt collection practices based on a Duke study that got wide media coverage. Allina’s dispute with 550 of its primary care providers seeking union representation based on their concerns about patient safety. Jefferson Health was called out for missteps under its prior administration’s “growth at all costs” agenda and the $35 million 2021 compensation for Common Spirit’s CEO received notice in industry coverage.

My take:

BSH represents an important alignment of health insurers with large employers who have shouldered a disproportionate share of health costs for years through the prices imposed for the hospitals, prescriptions and services their employees and dependents use.

Though it’s too early to predict how BSH vs. Corporate Hospitals will play out, especially in a divided Congress and with 2024 elections in 14 months, it’s important to inject a fair and balanced context for this contest as the article of war are unsealed:

- Health insurers and hospitals share the blame for high health costs along with prescription drug manufacturers and others. The U.S. system feasts on opaque pricing, regulated monopolies and supply-induced demand. Studies show unit costs for hospitals along with prescription drug costs bear primary responsibility for two-thirds of health cost increases in recent years—the result of increased demand and medical inflation. But insurers are complicit: benefits design strategies that pre-empt preventive health and add administrative costs are parts of the problem.

- Corporatization of the U.S. system cuts across every sector: Healthcare’s version of Moneyball is decidedly tilted toward bigger is better: in healthcare, that’s no exception. 3 of the top 10 in the Fortune 100 are healthcare (CVS-Aetna, United, McKesson)) and HCA (#66) is the only provider on the list. The U.S. healthcare industry is the largest private employer in the U.S. economy: how BSH addresses healthcare’s biggest employers which include its hospitals will be worth watching. And Big Pharma companies pose an immediate challenge: just last week, HHS called out the U.S. Chamber of Commerce for siding with Big Pharma against implementation of drug price controls in the Inflation Reduction Act—popular with voters but not so much in Big Pharma Board rooms.

- The focus will be on Federal health policies. BSH represents insurers and employers that operate across state lines–so do the majority of major health systems. Thus, federal rules, regulations, administrative actions, executive orders, and court decisions will be center-stage in the BSH v. corporate hospitals war. Revised national policies around Medicare and federal programs including military and Veterans’ health, pricing, equitable access, affordability, consolidation, monopolies, data ownership, ERISA and tax exemptions, patent protections and more might emerge from the conflict. As consolidation gets attention, the differing definitions of “markets” will require attention: technology has enabled insurers and providers to operate outside traditional geographic constraints, so what’s next? And, complicating matters, federalization of healthcare will immediately impact states as referenda tackle price controls, drug pricing, Medicaid coverage and abortion rights—hot buttons for voters and state officials.

- Boards of directors in each healthcare organization will be exposed to greater scrutiny for their actions: CEO compensation, growth strategies, M&A deals, member/enrollee/patient experience oversight, culture and more are under the direct oversight of Boards but most deflect accountability for major decisions that pose harm. Balancing shareholder interests against the greater good is no small feat, especially in a private health system which depends on private capital for its innovations.

8.6% of the U.S. population is uninsured, 41% of Americans have outstanding medical debt, and the majority believe health costs are excessive and the U.S. system is heading in the wrong direction.

Compared to other modern systems in the world, ours is the most expensive for its health services, least invested in social determinants that directly impact 70% of its costs and worst for the % of our population that recently skipped needed medical care (39.0% (vs. next closest Australia 21.2%), skipped dental care (36.2% vs. next closest Australia 31.7%) and had serious problems/ were unable to pay medical bills (22.4% next closest France 10.1%). Thus, it’s a system in which costs, prices and affordability appear afterthoughts.

Who will win BSH vs. Corporate Hospitals? It might appear a winner-take all showdown between lobbyists for BSH and hospital hired guns but that’s shortsighted. Both will pull out the stops to win favor with elected officials but both face growing pushback in Congress and state legislatures where “corporatization” seems more about a blame game than long-term solution.

Each side will use heavy artillery to advance their positions discredit the other. And unless the special interests that bolster efforts by payers are hospitals are subordinated to the needs of the population and greater good, it’s not the war to end all healthcare wars. That war is on the horizon.

Cartoon – You’ve Tested Positive

Biden administration proposes rollback of short-term health plan expansion

https://mailchi.mp/cc1fe752f93c/the-weekly-gist-july-14-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

Last Friday, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Treasury Department, and the Department of Labor jointly issued several proposed rules to shore up consumer healthcare protections, including reversal of a Trump administration policy that allowed consumers to enroll in short-term health plans, which were intended to serve as limited coverage options during transitional periods, for up to three years. Approximately 3M people were enrolled in these plans in 2019.

A new rule would limit consumer access to these plans to just three months, with an optional one-month extension, while also requiring payers to disclose clearly how their plans fall short of comprehensive health insurance.

The Gist: In an expected move, the Biden administration continues its unwinding of the Trump-era policies it sees as undermining the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) mission of guaranteeing robust, accessible insurance for all.

Short-term plans, which were granted an exemption from the ACA requirement that health plans cover ten essential health benefits, have been found to discriminate against people with pre-existing conditions, revoke coverage for enrollees retroactively, and generate excess surprise bills due to their limited networks.

How GLP-1 agonist drugs could change healthcare demand

https://mailchi.mp/edda78bd2a5a/the-weekly-gist-june-23-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

With more than two in five American adults considered obese, the potential for GLP-1 agonist drugs like Wegovy, Ozempic, and Mounjaro to revolutionize obesity treatment seems limitless.

In the graphic above, we looked to quantify how much these drugs could potentially change healthcare expenditures and demand. Using Wegovy’s list price of $1.3K per month, a GLP-1 drug prescription for every obese American adult would cost as much as $1.3T annually—30 percent of total US healthcare expenditures.

Analyst projections of GLP-1 drugs forecast revenue to grow by over 5x by 2028, from $3 billion to $16 billion annually. While it’s unlikely that every overweight American will access the drugs, growing use of GLP-1 agonists will likely drive down obesity rates, and downstream care demand could shift in expected and unpredictable ways. Demand for weight-related surgeries, including joint replacements and bariatric surgery, will likely drop. Incidence of chronic diseases like diabetes and cardiovascular disease could also drop, potentially raising life expectancy.

But even if we’re living longer thanks to the new drugs, we’ll still die of something eventually: expect a secondary rise in cancers and Alzheimer’s, as well as surging demand for eldercare. While these effects will take years to materialize, leaders planning for long-term care needs would be wise to consider scenarios where these and other potential “blockbuster” drugs may disrupt demand patterns and spending for a wide range of services.