While Congressional leaders play chicken with the debt ceiling this week, antipathy toward hospitals is mounting.

To be fair, hospitals are not alone: drug companies and PBMs share the distinction while health insurers, device companies, medical groups and long-term care providers enjoy less attention…for now.

Hospitals are soft targets. They’re also vulnerable.

They operate in a sector that’s labor intense, capital intense and highly regulated by federal, state and local governments. They’re high profile: many advertise regionally/nationally, all claim unparalleled clinical excellence and unfair treatment by health insurers.

Hospitals operate locally, so storylines like these get attention

- In Minnesota, Mississippi and Pennsylvania, hospitals are in court alleging under-payments and/or adverse coverage policies by dominant insurers in their markets.

- In NC, the state treasurer and others are challenging a unanimous State Senate vote last week granting the UNC Health System a waiver from antitrust concerns as it builds out its system.

- In CA, nurses are striking for higher wages, improved work conditions in 5 HCA hospitals.

- And in Nashville today, private equity-owned Envision will declare bankruptcy throwing its emergency room staffing contracts with hospitals into limbo.

The future for hospitals is unclear

Inpatient demand is shrinking/shifting. Outpatient, virtual, and in-home services demand is growing. Discontent among workers and employed physicians is palpable. Labor and supply chain costs wipe-out operating margins and price sensitivity among consumers and employers is soaring. Most are trying to survive any way they can. Some won’t.

Per Syntellis’ latest analysis, the tide may be turning:

- Total hospital expenses rose for an 11th consecutive month, but growth in labor expenses slowed for the first three months of 2023; Total Expense rose 4.7% YOY for the month while Total Non-Labor Expense rose 5.5% YOY due to higher costs for drugs, supplies, and purchased services. Total Labor Expense was up 1.8% YOY — a slight uptick after YOY labor expense increases eased to less than 1% in January and February.

- Hospital margins remained extremely narrow but inched back into the black for the first time in 15 months as revenue growth outpaced expense increases. The median, actual year-to-date Operating Margin was 0.4% for March, up from -1.1% in February.

- Surgery expenses increased despite lower volumes, while levels of patient care remained relatively steady.

Syntellis March Performance Report performance_trends_april_hc.1105.05.23.pdf (syntellis.com)

But no one knows for sure how long a full recovery will take, how debt ceiling negotiations will impact payments by Medicaid or Medicare or how court and antitrust actions by the DOJ will impact hospitals in the future.

What we know with a fair amount of confidence is this:

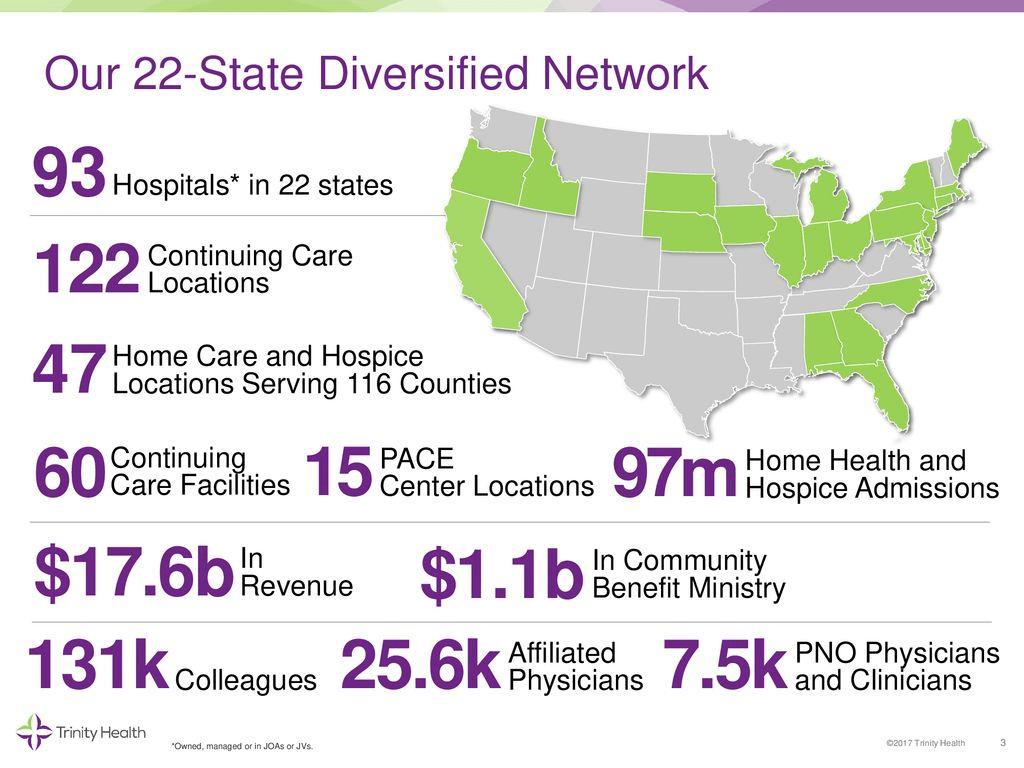

- Bigger organizations in each sector—hospitals, drug & device manufacturers, medical groups, and health insurers—will have advantages others don’t.

- Private equity will play a bigger role in the delivery and financing of care through strategic investments that drive low cost, high value alternatives for consumers and employers.

- Regulators will enact selective price controls in targeted domains of the health system.

- Large self-insured employers will be the primary catalyst for transformative changes.

- Inpatient demand will shrink and tertiary services will be centralized in regulated hubs.

- Structural remedies—convergence of social services and health systems, integration of financing and delivering care and direct alignment of insurer and provider incentives—will be key features of systemness choices to consumers and purchasing groups.

Most hospital boards of directors, especially not-for-profit organizations, are not prepared to calibrate the pace of these changes nor active in developing scenario possibilities for their future. That’s the place to start.

Post-pandemic recovery is not a technology-empowered 2.0 version of hospital operations: it is a fundamentally different business model based on new assumptions and bold leadership.