In late 2025, two events reset the U.S. health system’s future at least through 2026 and possibly beyond:

- November 5, 2024: The Election: Its post-mortem by pollsters and pundits reflects a country divided and unsettled: 22 Red States, 7 Swing States and 21 Blue States. But a solid majority who thought the country was heading in the wrong direction and their financial insecurity driving voters to return the 45th President to the White House. With slim majorities in the House and Senate, and a short-leash before mid-term elections November 3, 2026, the Trump team has thrown out ‘convention’ in their setting policies and priorities for their second term. That includes healthcare.

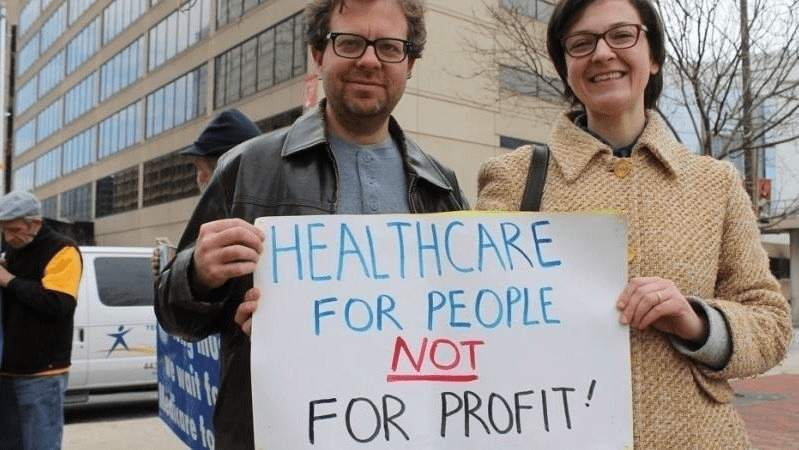

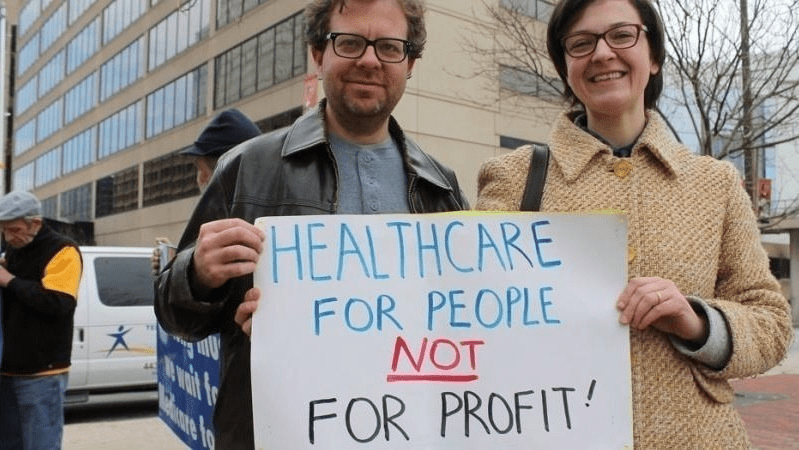

- December 4, 2024: The Murder of a Health Executive : The murder of Brian Thompson, United Healthcare CEO, sparked hostility toward health insurers and a widespread backlash against the corporatization of the U.S. health system. While UHG took the most direct hit for its aggressiveness in managing access and coverage disputes, social media and mainstream journalists exposed what pollsters affirmed—the majority of American’s distrust the health system, believing it puts its profits above their needs. And their polls indicate animosity is highest among young adults, in lower income households and among members of its own workforce.

These events provide the backdrop for what to expect this year and next. Four directional shifts seem to underly actions to date and announced plans:

- From elitism to populism: Key personnel and policy changes will draw less from Ivy League credentials, DC connections and recycled federal health agency notables and more from private sector experience, known disruptors and unconventional thought leaders. Notably, the new Chairs of the 7 Congressional Committees that control healthcare regulation, funding and policy changes in the 119th Congress represent LA, AL, WV, ID, VA, MO & KY constituents—hardly Ivy League territory.

- From workforce disparities to workforce modernization: The Departments of Health & Human Services, Labor, Commerce and Treasury will attempt to suspend/modify regulatory mandates and entities they deem derived from woke ideology. The Trump team will replace them with policies that enable workforce de-regulation and modernization in the private sector. Hiring quotas, non-compete contracts, DEI et al will get a fresh look in the context of technology-enabled workplaces and supply-demand constraints. The HR function in every organization will become ground zero for Trump Healthcare 2.0 system transformation.

- From western medicine to whole person wellbeing: HHS Secretary Nominee Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (RFK) Jr.’s “Make America Healthy Again” pledges war on ultra-processed foods. CMS’ designee Mehmet Oz advocates for vitamins, supplements and managed care. FDA nominee Marty Makary, a Hopkins surgeon, is a RFKJ ally in the “Health Freedom” movement promoting suspicion about ‘mainstream medicine’ and raising doubts about vaccination efficacy for children and low-risk adults. NIH nominee Jay Bhattacharya, director of Stanford’s Center for Demography and Economics of Health and Aging, opposed Covid-19 lockdowns and is critical of vaccine policies. Collectively, this four-some will challenge conventional western (allopathic) medicine and add wide-range of non-traditional interventions that are a safe and cost-effective to the treatment arsenal for providers and consumers. The food supply will be a major focus: HHS will work closely with the USDA (nominee Brooke Rollins, currently CEO of the America First Policy Institute, to reduce the food chain’s dependence on ultra-processed foods in public health.

- From DC dominated health policies to states: The 2022 Supreme Court’ Dobbs decision opened the door for states to play the lead role in setting policies for access to abortion for their female citizens. It follows federalism’s Constitutional preference that Washington DC’s powers over states be enumerated and limited. Thus, state provisions about healthcare services for its citizens will expand beyond their already formidable scope. Likely actions in some states will include revised terms and conditions that facilitate consolidation, allowance for physician owned hospitals and site-neutral payments, approval of “skinny” individual insurance policies that do not conform to the Affordable Care Act’s qualified health plan spec’s, expanded scope of practice for nurse practitioners, drug price controls and many others. At least for the immediate future, state legislatures will be the epicenters for major policy changes impacting healthcare organizations; federal changes outside appropriations activity are unlikely.

Transforming the U.S. health system is a bodacious ambition for the incoming Trump team. Early wins will be key—like expanding price transparency in every healthcare sector, softening restrictions on private equity investments, targeted cuts in Medicaid and Medicare funding and annulment of the Inflation Reduction Act. In tandem, it has promised to cut Federal government spending by $2 trillion and lower prices on everything including housing and healthcare—the two spending categories of highest concern to the working class. Healthcare will figure prominently in Team Trump’s agenda for 2025 and posturing for its 2026 mid-term campaign. And equally important, healthcare costs also figure prominently in quarterly earnings reports for companies that provide employee health benefits forecast to be 8% higher this year following a 7% spike the year prior. Last year’s 23% S&P growth is not expected to repeat this year raising shareholder anxiety and the economy’s long-term resilience and the large roles housing and healthcare play in its performance.

My take:

The 2024 election has been called a change election. That’s unwelcome news to most organizations in healthcare, especially the hospitals, physicians, post-acute providers and others who provide care to patients and operate at the bottom of the healthcare pyramid.

Equipping a healthcare organization to thoughtfully prepare for changes amidst growing uncertainty requires extraordinary time and attention by management teams and their Boards. There are no shortcuts. Before handicapping future state scenario possibilities, contingencies and resource requirements, a helpful starting point is this: On the four most pressing issues facing every U.S. healthcare company/organization today, Boards and Management should discuss…

- Trust: On what basis can statements about our performance be verified? Is the data upon which our trust is based readily accessible? Does the organization’s workforce have more or less trust than outside stakeholders? What actions are necessary to strengthen/restore trust?

- Purpose: Which stakeholder group is our organization’s highest priority? What values & behaviors define exceptional leadership in our organization? How are they reflected in their compensation?

- Affordability: How do we measure and monitor the affordability of our services to the consumers and households we ultimately depend? How directly is our organization’s alignment of reducing cost reduction and pass-through savings to consumers? Is affordability a serious concern in our organization (or just a slogan)?

- Scale: How large must we be to operate at the highest efficiency? How big must we become to achieve our long-term business goals?

This week, thousands of healthcare’s operators will be in San Francisco (JPM Healthcare Conference), Naples (TGI Leadership Conference) and in Las Vegas (Consumer Electronics Show) as healthcare begins a new year. No one knows for sure what’s ahead or who the winners and losers will be. What’s for sure is that healthcare will be in the spotlight and its future will not be a cut and paste of its past.

PS: The parallels between radical changes facing the health system and other industries is uncanny. College athletics is no exception. As you enjoy the College Football Final Four this weekend, consider its immediate past—since 2021, the impact of Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) monies on college athletics, and its immediate future–pending regulation that will codify permanent revenue sharing arrangements (to be implemented 2026-2030) between college athletes, their institutions and sponsors. What happened to the notion of student athlete and value of higher education? Has the notion of “not-for-profit” healthcare met a similar fate? Or is it all just business?