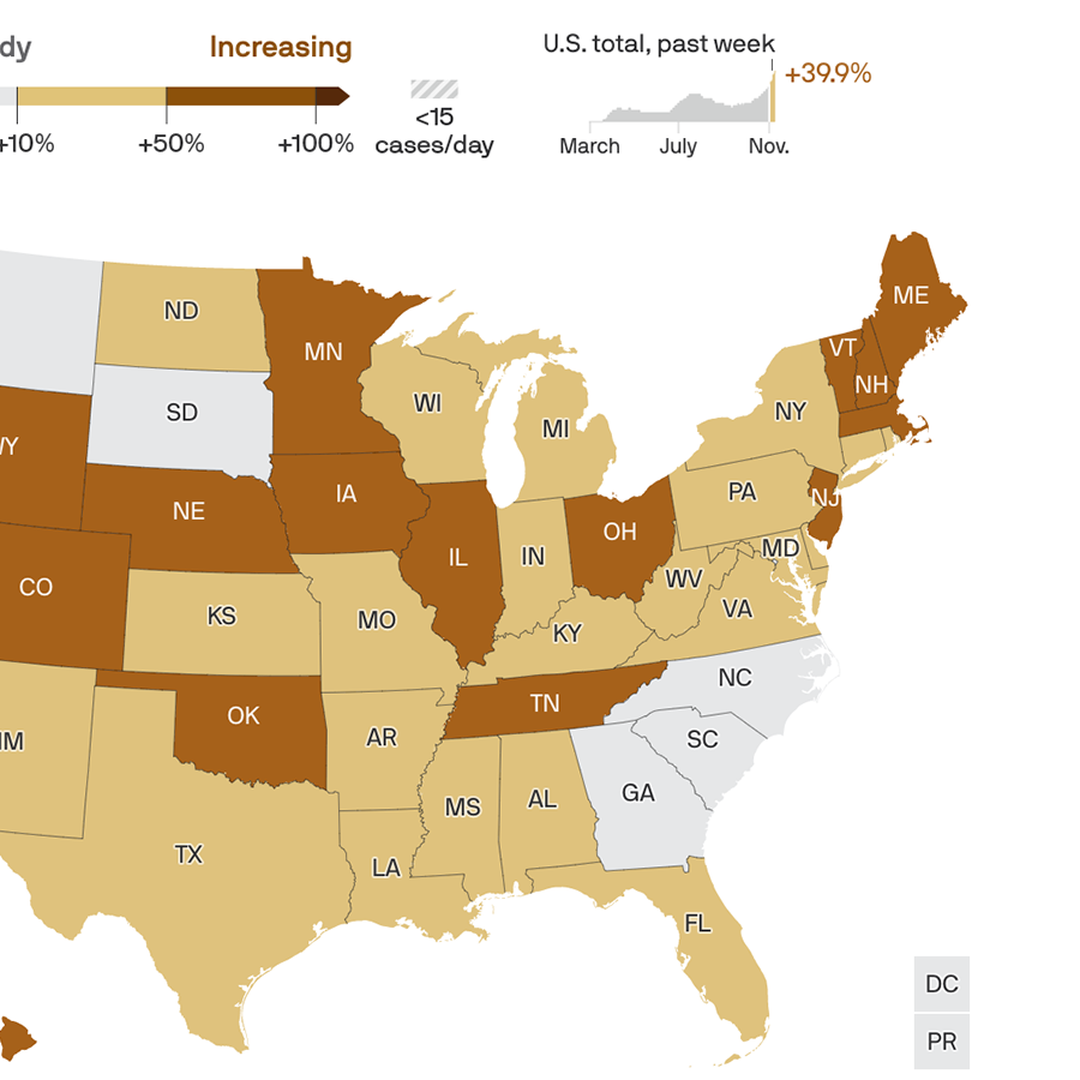

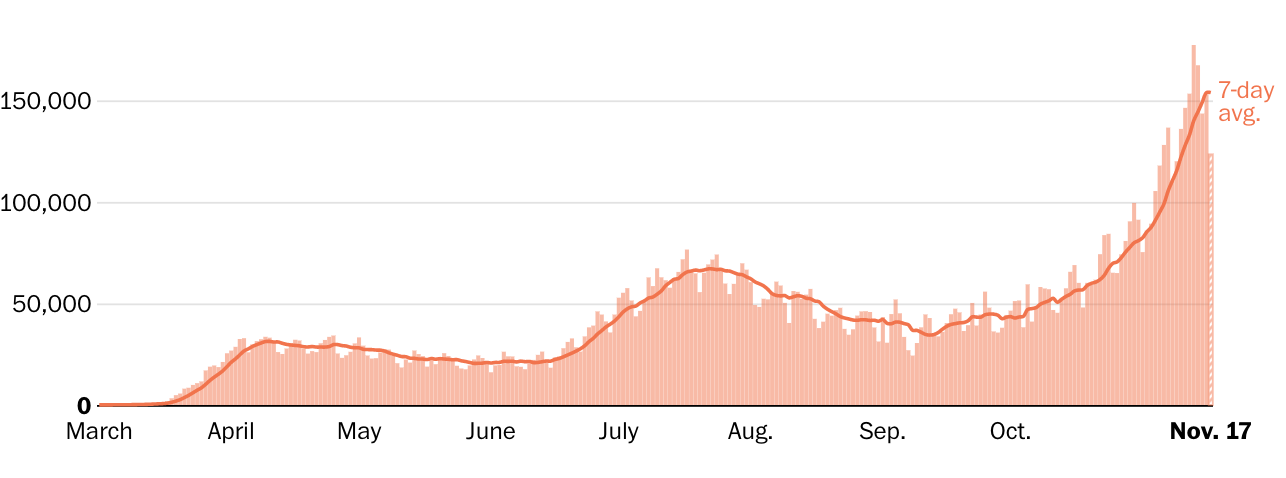

As record numbers of coronavirus cases overwhelm hospitals across the United States, there is something strikingly different from the surge that inundated cities in the spring: No one is clamoring for ventilators.

The sophisticated breathing machines, used to sustain the most critically ill patients, are far more plentiful than they were eight months ago, when New York, New Jersey and other hard-hit states were desperate to obtain more of the devices, and hospitals were reviewing triage protocols for rationing care. Now, many hot spots face a different problem: They have enough ventilators, but not nearly enough respiratory therapists, pulmonologists and critical care doctors who have the training to operate the machines and provide round-the-clock care for patients who cannot breathe on their own.

Since the spring, American medical device makers have radically ramped up the country’s ventilator capacity by producing more than 200,000 critical care ventilators, with 155,000 of them going to the Strategic National Stockpile. At the same time, doctors have figured out other ways to deliver oxygen to some patients struggling to breathe — including using inexpensive sleep apnea machines or simple nasal cannulas that force air into the lungs through plastic tubes.

But with new cases approaching 200,000 per day and a flood of patients straining hospitals across the country, public health experts warn that the ample supply of available ventilators may not be enough to save many critically ill patients.

“We’re now at a dangerous precipice,” said Dr. Lewis Kaplan, president of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Ventilators, he said, are exceptionally complex machines that require expertise and constant monitoring for the weeks or even months that patients are tethered to them. The explosion of cases in rural parts of Idaho, Ohio, South Dakota and other states has prompted local hospitals that lack such experts on staff to send patients to cities and regional medical centers, but those intensive care beds are quickly filling up.

Public health experts have long warned about a shortage of critical care doctors, known as intensivists, a specialty that generally requires an additional two years of medical training. There are 37,400 intensivists in the United States, according to the American Hospital Association, but nearly half of the country’s acute care hospitals do not have any on staff, and many of those hospitals are in rural areas increasingly overwhelmed by the coronavirus.

“We can’t manufacture doctors and nurses in the same way we can manufacture ventilators,” said Dr. Eric Toner, an emergency room doctor and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “And you can’t teach someone overnight the right settings and buttons to push on a ventilator for patients who have a disease they’ve never seen before. The most realistic thing we can do in the short run is to reduce the impact on hospitals, and that means wearing masks and avoiding crowded spaces so we can flatten the curve of new infections.”

Medical association message boards in states like Iowa, Oklahoma and North Dakota are awash in desperate calls for intensivists and respiratory therapists willing to temporarily relocate and help out. When New York City and hospitals in the Northeast issued a similar call for help this past spring, specialists from the South and the Midwest rushed there. But because cases are now surging nationwide, hospital officials say that most of their pleas for help are going unanswered.

Dr. Thomas E. Dobbs, the top health official in Mississippi, said that more than half the state’s 1,048 ventilators were still available, but that he was more concerned with having enough staff members to take care of the sickest patients.

“If we want to make sure that someone who’s hospitalized in the I.C.U. with the coronavirus has the best chance to get well, they need to have highly trained personnel, and that cannot be flexed up rapidly,” he said in a news briefing on Tuesday.

Dr. Matthew Trump, a critical care specialist at UnityPoint Health in Des Moines, said that the health chain’s 21 hospitals had an adequate supply of ventilators for now, but that out-of-state staff reinforcements might be unlikely to materialize as colleagues fall ill and the hospital’s I.C.U. beds reach capacity.

“People here are exhausted and burned out from the past few months,” he said. “I’m really concerned.”

The domestic boom in ventilator production has been a rare bright spot in the country’s pandemic response, which has been marred by shortages of personal protective equipment, haphazard testing efforts and President Trump’s mixed messaging on the importance of masks, social distancing and other measures that can dent the spread of new infections.

Although the White House has sought to take credit for the increase in new ventilators, medical device executives say the accelerated production was largely a market-driven response turbocharged by the national sense of crisis. Mr. Trump invoked the wartime Defense Production Act in late March, but federal health officials have relied on government contracts rather than their authority under the act to compel companies to increase the production of ventilators.

Scott Whitaker, president of AdvaMed, a trade association that represents many of the country’s ventilator manufacturers, said the grave situation had prompted a “historic mobilization” by the industry. “We’re confident that our companies are well positioned to mobilize as needed to meet demand,” he said in an email.

Public health officials in Minnesota, Mississippi, Utah and other states with some of the highest per capita rates of infection and hospitalization have said they are comfortable with the number of ventilators currently in their hospitals and their stockpiles.

Mr. Whitaker said AdvaMed’s member companies were making roughly 700 ventilators a week before the pandemic; by the summer, weekly output had reached 10,000. The juggernaut was in part fueled by unconventional partnerships between ventilator companies and auto giants like Ford and General Motors.

Chris Brooks, chief strategy officer at Ventec Life Systems, which collaborated with G.M. to fill a $490 million contract for the Department of Health and Human Services, said the shared sense of urgency enabled both companies to overcome a thicket of supply-chain and logistical challenges to produce 30,000 ventilators over four months at an idled car parts plant in Indiana. Before the pandemic, Ventec’s average monthly output was 100 to 200 machines.

“When you’re focused with one team and one mission, you get things done in hours that would otherwise take months,” he said. “You just find a way to push through any and all obstacles.”

Despite an overall increase in the number of ventilators, some researchers say many of the new machines may be inadequate for the current crisis. Dr. Richard Branson, an expert on mechanical ventilation at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and an author of a recent study in the journal Chest, said that half of the new devices acquired by the Strategic National Stockpile were not sophisticated enough for Covid-19 patients in severe respiratory distress. He also expressed concern about the long-term viability of machines that require frequent maintenance.

“These devices were not built to be stockpiled,” he said.

The Department of Health and Human Services, which has acknowledged the limitations of its newly acquired ventilators, said the stockpile — nine times as large as it was in March — was well suited for most respiratory pandemics. “These stockpiled devices can be used as a short-term, stopgap buffer when the immediate commercial supply is not sufficient or available,” the agency said in a statement.

Projecting how many people will end up requiring mechanical breathing assistance is an inexact science, and many early assumptions about how the coronavirus affects respiratory function have evolved.

During the chaotic days of March and April, emergency room doctors were quick to intubate patients with dangerously low oxygen levels. They subsequently discovered other ways to improve outcomes, including placing patients on their stomachs, a protocol known as proning that helps improve lung function. The doctors also learned to embrace the use of pressurized oxygen delivered through the nose, or via BiPAP and CPAP machines, portable devices that force oxygen into a patient’s airways.

Many health care providers initially hesitated to use such interventions for fear the pressurized air would aerosolize the virus and endanger health care workers. The risks, it turned out, could be mitigated through the use of respirator masks and other personal protective gear, said Dr. Greg Martin, the chief of pulmonary and critical care at Grady Health Systems in Atlanta.

“The familiarity of taking care of so many Covid patients, combined with good data, has just made everything we do 100 times easier,” he said.

Some of the earliest data about the perils of intubating coronavirus patients turned out to be incomplete and misleading. Dr. Susan Wilcox, a critical care specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital, said many providers were spooked by data that suggested an 80 percent mortality rate among ventilated coronavirus patients, but the actual death rate turned out to be much lower. The mortality rate at her hospital, she said, was about 25 to 30 percent.

“Some people were saying that we should intubate almost immediately because we were worried patients would crash and have untoward consequences if we waited,” she said. “But we’ve learned to just go back to the principles of good critical care.”

Survival rates have increased significantly at many hospitals, a shift brought about by the introduction of therapeutics like dexamethasone, a powerful steroid that Mr. Trump took when he was hospitalized with the coronavirus. The changing demographics of the pandemic — a growing proportion of younger patients with fewer health risks — have also played a role in the improving survival rates.

Dr. Nikhil Jagan, a critical care pulmonologist at CHI Health, a hospital chain that serves Iowa, Kansas and Nebraska, said many of the coronavirus patients who were arriving at his emergency room now were less sick than the patients he treated in the spring.

“There’s a lot more awareness about the symptoms of Covid-19,” he said. “The first go-around, when people came in, they were very sick right off the bat and in respiratory distress or at the point of respiratory failure and had to be intubated.”

But the promising new treatments and enhanced knowledge can go only so far should the current surge in cases continue unabated. The country passed 250,000 deaths from the coronavirus last week, a reminder that many critically ill patients do not survive. The daily death toll has been rising steadily and is approaching 2,000.

“Ventilators are important in critical care but they don’t save people’s lives,” said Dr. Branson of the University of Cincinnati. “They just keep people alive while the people caring for them can figure out what’s wrong and fix the problem. And at the moment, we just don’t have enough of those people.”

For now, he said there was only one way out the crisis: “It’s not that hard,” he said. “Wear a mask.”