Medicare Advantage Majority and Better Medicare Alliance are flooding the zone with attacks against bipartisan legislation aimed at curbing health insurers’ “upcoding” maneuver.

HEALTH CARE un-covered readers were the first to tip me off to television attack ads against the bipartisan No UPCODE Act, sponsored by Senators Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and Jeff Merkley (D-OR). The ads in question, airing in the Washington D.C. media market, were paid for by Medicare Advantage Majority (MAM), which bills itself as a patient and provider coalition but has all the markings of a front group funded by the nation’s largest health insurers.

After a quick search through MAM’s YouTube channel, I think I found the ad I was tipped about. Titled “Voices,” the video features six seniors fawning over their Medicare Advantage plans – and it ends with a desperate plea to “oppose the No UPCODE Act” and “protect Medicare Advantage.”

MAM appears to have been propped up fairly recently – with their earliest ad (that I can find) from October 2024. All of their ads support Medicare Advantage. Some appear nonpartisan, while others are more overtly political, like the ad “Biden’s Playbook.” Here is a transcription of that ad:

“President Trump kept his promise to protect Medicare benefits for millions of American seniors. But now some in Congress want to take a page out of Joe Biden’s playbook and cut Medicare. These cuts threaten primary and preventative care that help keep millions of seniors healthy while also raising costs.

It’s a betrayal. It’s why people don’t trust Washington. Don’t let the politicians cut Medicare. Tell Congress to stand with President Trump and protect America’s seniors.”

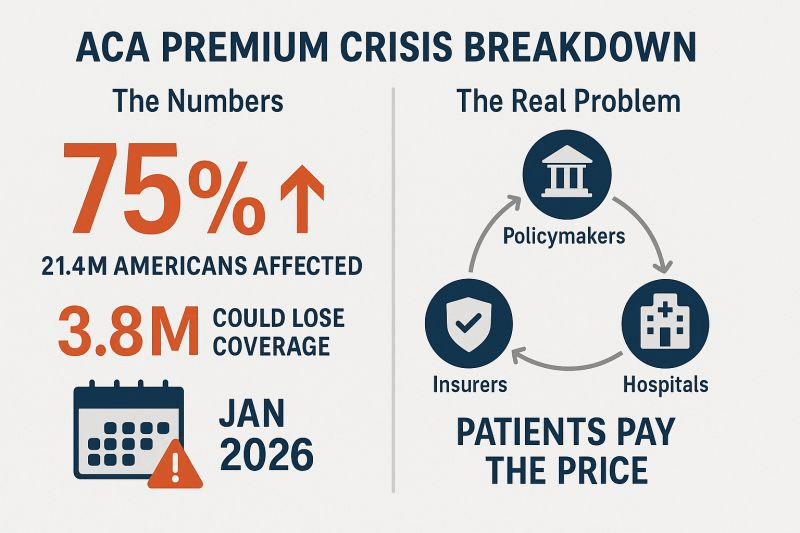

None of MAM’s ads mention the expensive hidden fees, narrow networks of doctors and life-threatening prior-authorization hurdles often associated with private Medicare Advantage plans. Nor does it even hint at why Sen. Cassidy, a doctor and senior Republican leader and committee chair, introduced the No UPCODE Act in the first place: to reduce the tens of billions of dollars in overpayments to Medicare Advantage insurers and keep the Medicare Trust Fund solvent for years longer. Those overpayments – at least $84 billion this year alone – is a leading reason why the Medicare Trust Fund is being depleted.

But Medicare Advantage Majority is not the only insurance industry front group flooding the zone.

I kid you not, while I was writing this very article I got a text from a different Big Insurance-funded group fear-mongering the same “cuts” to Medicare Advantage. As I’m typing away on my laptop, my phone dings… The first words in the text read: “ATTENTION NEEDED:”. The message had all the hallmarks of a cookie-cutter political blast that was cooked up by some DNC-alum or K Street PR strategist.

When I followed the prompt and clicked on the link, it took me to one of the industry’s most trusted hands in the Medicare Advantage fight, the Better Medicare Alliance (BMA) – one of my former colleagues’ most essential propaganda shops these days.

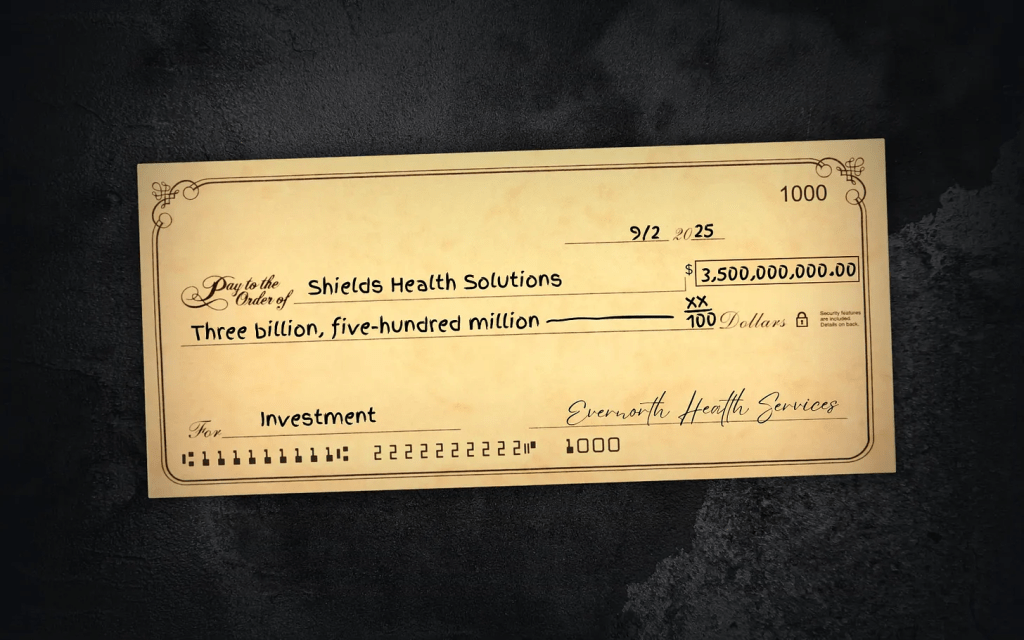

BMA is a slickly branded PR and lobbying shop that presents itself as a coalition of “advocates” working to protect seniors’ care, but it’s heavily funded by private insurers in the MA business who reap billions in those overpayments from taxpayers each year. BMA’s board has been stacked with Humana and UnitedHealth representatives and allies tied to medical schools like Emory and Meharry Medical College. For years, they’ve spent millions lobbying and propagating to protect MA insurers’ profits. This includes rallying against the No UPCODE Act since July; opposing CMS’ risk adjustment model in 2024 (which should help reduce some of the overpayments); and objecting vigorously to any Medicare Advantage plan payment reductions, year in and year out.

In short, BMA and MAM are both 501(c)(4) “social welfare” nonprofits used by Big Insurance as part policy shop, part lobbying arm, and part attack dog. Together, they make up a strategy for insurers that want to keep their MA cash cows gorging on your money.

None of this is new, though. It’s the same PR crap I used to fling back in the old days when I was an industry executive and had to peddle Medicare Advantage plans. (Its deliciously ironic that MAM had the audacity to use the term “playbook” in one of its ads. In my old job I used to help write the industry’s playbook.) Each fall we’d work with AHIP (formerly America’s Health Insurance Plans) to host “Granny Fly-Ins” in Washington, D.C. Industry money (actually, taxpayer money) would cover the fly-in expenses, and the seniors would trot around Capitol Hill to extol the supposed benefits of Medicare Advantage plans and dare lawmakers to tamper with it. And that tactic worked for years. Of course, this was all before texting existed.

The squeal tells the story

For years, MA insurers have exaggerated how sick their patients are on paper (making them seem sicker so they can get a bigger taxpayer-funded handout). Hence the term “upcoding.” And the sick joke is – unfortunately – the same insurers who profit most from this upcoding scheme are using their taxpayer loot to stop this bill from gaining traction.

I think the industry’s squeal tells the story.

Let’s be real: Big Insurance wouldn’t be running this PR and lobbying blitz unless this legislation really would do some major good for Americans. The No UPCODE Act is a strong, bipartisan step toward ending wasteful, fraudulent practices that funnel taxpayer money into the pockets of industry executives and Wall Street shareholders. This one bill could save taxpayers as much as $124 billion over the next decade and keep the Medicare Trust Fund solvent for years longer.

You can be sure, though, that people on Capitol Hill and the administration already know ads like these are industry-funded. They see them for what they really are — part of a well-financed intimidation campaign. A game. Running ads like these is the industry’s way of flaunting its power and a reminder that big money can and will be spent in Congressional campaigns — and possibly (again) even during the Super Bowl — to mislead voters.

So remember, when you see an ad or get a text from an organization like MAM or BMA – know that these organizations have a lot to lose if legislation like the No UPCODE Act becomes law. And spending your premium and tax dollars on text blasts and TV spots are well worth the investment – to them, anyway.