Highlighting a key implication of the rise in high-deductible health plans, both on the ACA exchanges and in employer-sponsored insurance, the article describes a question now commonly faced by doctors and hospitals—how best to collect their patients’ portion of the fees they charge? As one Texas doctor tells Bloomberg, reflecting the experience of the Maldonados from the other side of the equation, “If [patients] have to decide if they’re going to pay their rent or the rest of our bill, they’re definitely paying their rent.” He reports that the number of people dodging his calls to discuss payment has increased “tremendously” since the passage of the ACA. Another Texas doctor reports that his small practice had to add an additional full-time staff member just to collect money owed by patients, adding further overhead to his practice’s costs and making it more likely that he, like many other doctors, will eventually seek shelter by being employed by a larger delivery organization. That trend, as has been repeatedly shown, further increases the cost of care, exacerbating the increase in insurance costs for families like the Maldonados. This Gordian knot of increasing costs, rising deductibles, and growing premiums has left us with a healthcare system that’s forcing difficult decisions at every turn, for patients and providers.

Physicians, hospitals and medical labs are grappling with the rise in high-deductible insurance.

Doctors, hospitals and medical labs used to be concerned about patients who didn’t have insurance not paying their bills. Now they’re scrambling to get paid by the ones who do have insurance.

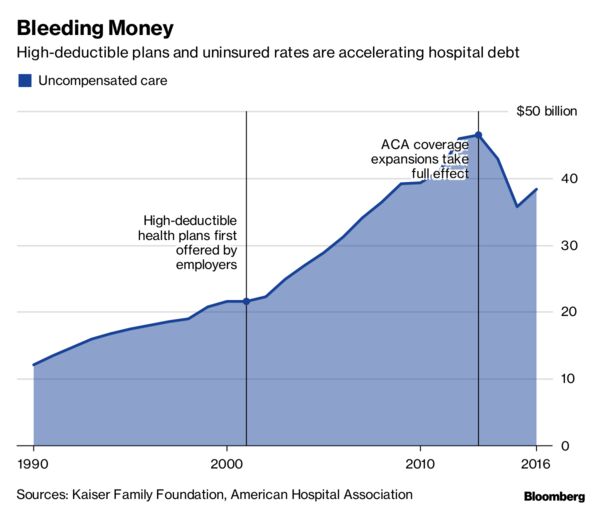

For more than a decade, insurers and employers have been shifting the cost of care onto their workers and customers, tamping down premiums by raising patients’ out-of-pocket costs. Last year, almost half of privately insured Americans under age 65 had annual deductibles ranging from $1,300 to as high as $6,550, government data show.

“It’s harder to collect from the patient than it is from the insurance,” said Amy Derick, a doctor who heads a dermatology practice outside Chicago. “If the plans change to a higher deductible, it’s harder to get the patients to pay.”

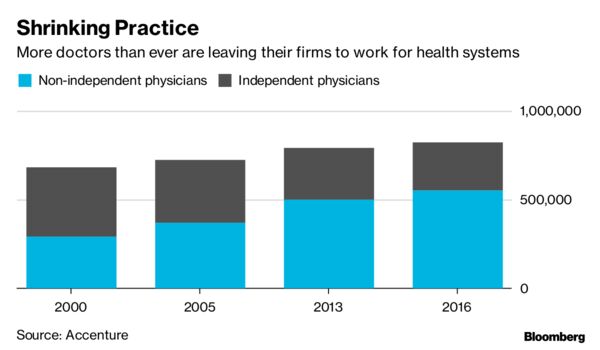

Independent physicians cited reimbursement pressures as their biggest concern for staying in business, according to a report by Accenture Plc in 2015.

“If they have to decide if they’re going to pay their rent or the rest of our bill, they’re definitely paying their rent,” said Gerald “Ray” Callas, president of the Texas Society of Anesthesiologists, whose Beaumont, Texas, practice treats about 40,000 people annually. “We try to work with the patient, but on the other hand, we can’t do it for free because we still maintain a small business.”

In 2016, Callas introduced payment options that allow patients with expensive plans to pay a portion of the bill upfront or on a monthly basis over several years. Even so, Callas said the number of people avoiding his calls after surgery has increased “tremendously” each year since the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010.

Derick instituted a “time-out” option a few years back that gives patients the billing codes before a procedure, allowing them to call their insurance companies for estimates. Even with the program, collection rates are slower, especially at the beginning of the year when insurance plan deductibles reset.

Even large medical companies with national operations are facing the problem. Quest Diagnostics Inc., the lab-testing giant, said 20 percent of services billed to patients in the third quarter of this year went unpaid, costing the company about $80 million in lost revenue.

“We certainly have a high bad-debt rate for the uninsured,” Chief Financial Officer Mark Guinan said in a telephone interview. “But really the biggest driver is people with insurance. It’s their coinsurance and their high deductibles, and they don’t always pay their bills.”

Another testing company, Laboratory Corp. of America Holdings, reported its first year-over-year uptick in unpaid bills in the first quarter of 2016. At the time, Chief Executive Officer David King said high-deductible plans, higher copays and greater incidences of non-covered services led to more dollars being shifted to patients. LabCorp declined requests for comment.

Northwell Healthcare Inc., a network of more than 700 hospitals and outpatient facilities, lost $106.9 million to unpaid services in 2015. Others have reported the same: Acute-care and critical-access hospitals reported$55.9 billion in bad debt for 2015, according to data compiled by the American Hospital Directory Inc.

“High-deductible plans have had a very big impact,” said Richard Miller, Northwell’s chief business strategy officer.

When it comes to reimbursement, a common denominator across the health-care industry is the archaic process through which bills are processed — a web of medical records, billing systems, health insurers and contractors.

High deductibles only add to the red tape. Providers don’t have real-time, fully accurate information on patient deductibles, which fluctuate based on how much has already been paid. That forces providers to constantly reach out to insurance companies for estimates.

Tarek Fakhouri, a Texas surgeon specializing in skin cancer, had to hire an additional staff member just to reason through bills with patients and their insurers, a big expense for an office of six or seven employees. About 10 percent of Fakhouri’s patients need payment plans, delay their skin-cancer surgeries until they’ve met their deductibles, or have to choose an alternative treatment.

According to a study earlier this year by the Journal of American Medical Association, primary-care physicians at academic health-care systems lose about 15 percent of their revenue to billing activities like calling insurance companies for estimates.

“It’s an unnecessary added cost to the health-care system to have to hire staff just to sit there on hold with insurance companies to find out what a patient’s deductible status is,” said Fakhouri.

Callas, Derick, and Fakhouri said they all know physicians who have left private practice altogether, some for the sole purpose of ending their dual roles as bill collectors. According to a study by the American Medical Association, less than half of doctors were self-employed as of 2016 — the lowest total ever. Many left their own practices in favor of hospitals and large physician groups with more resources.

To cope with the challenge, labs and hospitals are investing millions in programs designed to help patients understand what they owe at the point of care. Northwell has been implementing call centers and facilities where patients can ask questions about their bills.

“There’s a burden on both sides,” said Callas. “But health-care providers get caught in the middle.”