Atul Gawande is outlandishly accomplished. The son of Indian immigrants, he grew up in Athens, Ohio, and was educated at Athens High School, Stanford, Oxford, and Harvard, where he studied issues of public health. Before working as a surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston, he advised such politicians as Jim Cooper and Bill Clinton. He teaches at Harvard and is the chairman of Ariadne Labs, which works on innovation in health-care delivery and solutions, and he recently spent two years as the C.E.O. of a health-care venture called Haven, which is co-owned by Amazon, JPMorgan Chase, and Berkshire Hathaway.

Gawande is also a writer, and he has been publishing in The New Yorker for more than two decades. In 2009, heading into the debate over the Affordable Care Act, President Obama told colleagues that he had been deeply affected by Gawande’s article in the magazine called “The Cost Conundrum,” a study conducted in McAllen, Texas. Obama made the piece required reading for his staff. Gawande’s most recent book, a Times No. 1 best-seller, is “Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End.”

Since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, Gawande has been sharp in his criticism of the Trump Administration and, like Anthony Fauci and other prominent figures in public health, insistent on clear, basic measures to reduce levels of disease. After the election in November, President-elect Biden formed a covid-19 advisory board and included Gawande among its members. Earlier this week, I spoke with Gawande for The New Yorker Radio Hour. In the interview, which has been edited for length and clarity, Gawande says that President Trump’s relative silence on the issue after the election might be a blessing (considering the alternative). He suggests that the development of vaccines promises great things down the line, a return to relative normalcy some months from now. But, before that happens, he says, we may not only see terrible rates of illness and death—we will also experience an almost inevitably contentious rollout of the vaccine. Questions of who gets the vaccine and when will test a deeply divided society. As Gawande put it, “The bus drivers never came before the bankers before.”

We currently have one of the highest death and transmission rates of covid-19 in the world. What went wrong?

There’s so many things that went wrong, but you can boil it down to the difficulty of pulling together. One of the most critical things you have in the toolbox in public health is communications. It’s your ability to have clear priorities and communication about those priorities to your own public and to all of the players who get stuff done. We didn’t get testing started early. We weren’t calling the laboratories together to get testing built and created right from the get-go. And then fast-forward to where we are today. We still are in a world where we have not had clear communications from the top of the government around whether we should be wearing masks and having an actual national strategy to fight the virus. I would boil down what went wrong to not committing to communicating clearly and with one voice about the seriousness of what we’re up against and what the measures are to solve it.

When this began, I read “The Great Influenza,” John M. Barry’s book about 1918 and the horrendous flu that killed millions worldwide, and many hundreds of thousands in the United States. I thought to myself, Well, it’s not possible that we would repeat these mistakes, because, after all, we learn from history, even if the President of the United States does not. How is it possible that we made these same mistakes on such a mass scale? Do you lay it all at the feet of the President?

There’s a big part of this that I lay at the feet of the President. Imagine Pearl Harbor happened, and then we spent seven or eight months deciding whether or not we were going to fight back. And then, seven or eight months into it, a new President is going to come in who says, O.K., we are going to fight now. But you now have substantial parts of the country already arrayed against the idea that fighting it is worthwhile. In the meantime, some states have fought the attack and other states have not, and they’ve had to compete with each other for supplies. That’s the mess we have.

In May, I got to write about this in The New Yorker: the hospitals learned how to bring people to work and have them succeed. It was a formula that included masks, included some basic hygiene, some basic distancing, and testing. That’s been the formula, and is the formula still, for making it possible for people to resume a normal life. But we did not have a commitment from the very top to make this happen on a national basis. And we are continuing to litigate that issue to this very day.

You are now on President-elect Biden’s advisory board on covid-19, and I wonder what kind of coöperation you’re getting from the Trump Administration’s own advisory board.

Well, remember: up until just a few days ago, there was no contact allowed at all between any Administration officials and the Biden-Harris transition team. So only in the last few days have there started to be the contacts that would allow for basic information to be passed. I think it’s too early to say how well those channels of communication are turning out.

I’m sorry to interrupt, Atul, but, just to be clear here: we’re in a public-health emergency. Are you saying that the President’s theories, ill-founded and fantastical theories about the election, held up any communication whatsoever between President Trump’s advisory board and President-elect Biden’s board?

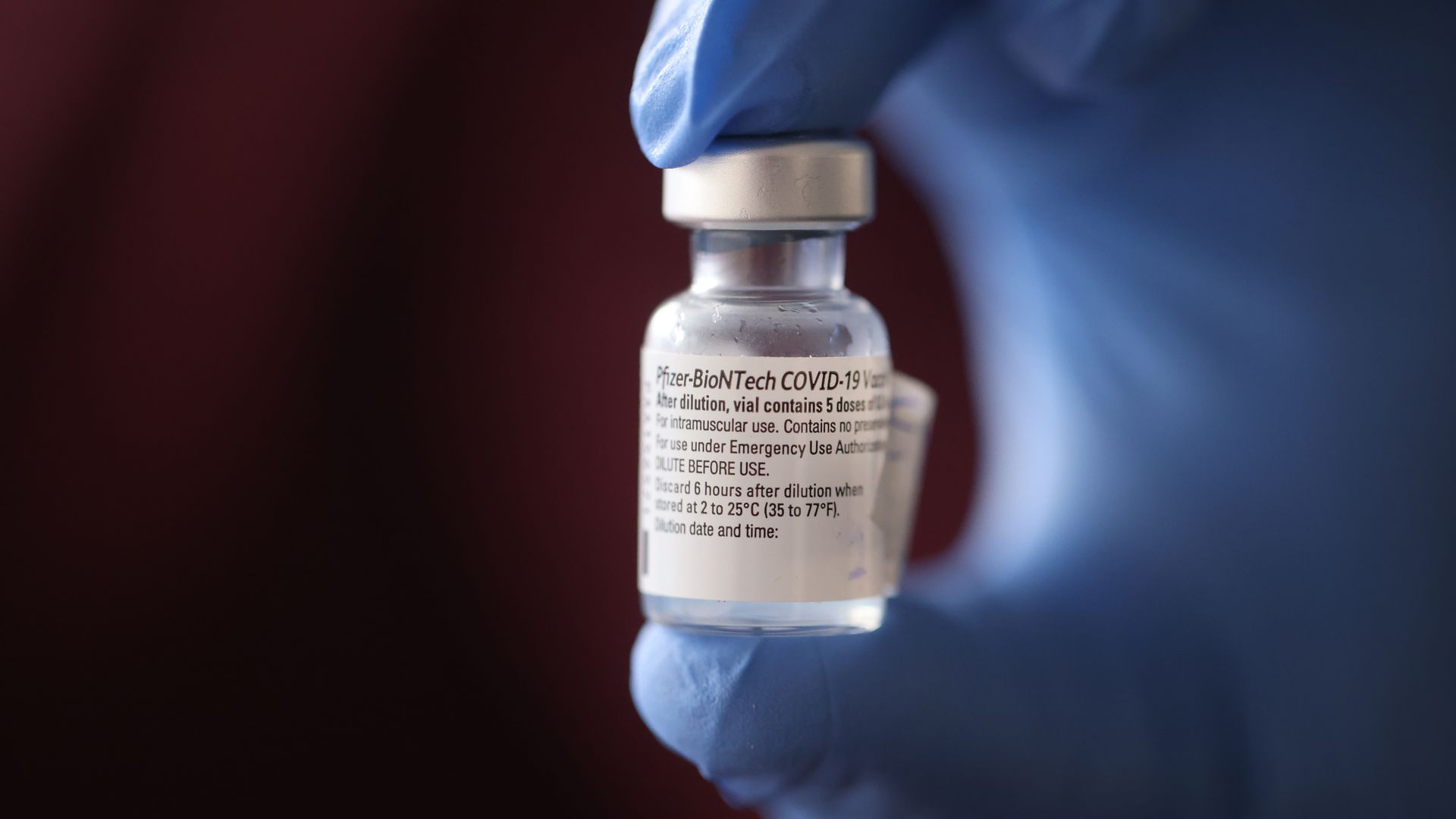

Absolutely. And I want to put a pin in what that means, in concrete fact. Here, we had a vaccine trial that came out three weeks ago showing a successful, effective vaccine, followed, just a few days later, by another vaccine trial. We did not have access to the information they were getting about the status of those trials. We did not have access to information about supplies. So, at the beginning of the year, with Operation Warp Speed, the target was three hundred million vaccines produced by the end of the year. Instead, what we’re seeing is reportedly thirty million or so by the end of [December]. We’re seeing in the press some backtracking from that as well. What were the bottlenecks that meant that this couldn’t be done? Is it a shortage of raw ingredients? Are they having stockpile problems? Is it a problem with the actual production processes?

Here’s another one when I’m talking to colleagues around the country who are going to be involved in distributing the vaccine: We hear about everything from shortages of gloves, uncertainty about supplies of needles and syringes for three hundred and thirty million people to get two rounds of doses. There’s no information yet on how many vaccines will be allocated to a given state or a given big pharmacy company like CVS or Walgreens—places that are an important part of the distribution chain. So there’s a lot of basic information that hasn’t been known. That discovery process is just starting.

The Biden Administration-to-be’s covid-19 task force has got a seven-point plan to stop the pandemic. What are the crucial elements of that plan?

It’s the same story that we’ve known since April: It’s mandating masks—that’s one of the most important tools we have for driving transmission down. It’s testing and being able to make sure that there’s widespread availability of testing. It’s supplies for the places that are going to need proper gloves, masks, et cetera. It’s continuing, based on the level of spread in a given community, to tune how much capacity restriction you have on indoor environments, whether it’s bars and restaurants or weddings or other gatherings that are seen to be currently driving transmission. Those are all critical elements. I’m firmly in agreement with where the President-elect is going on heeding the advice from public-health people that schools can be opened. But, in order for kids to be back in schools, especially elementary and middle schools, there’s still a lot of work to do to insure they have the supplies that they need to maintain distancing, to have the right ventilation.

Thanksgiving was a week ago. Anthony Fauci says that what he fears is a spike on top of a spike, a leap on top of a leap. Do you share that fear?

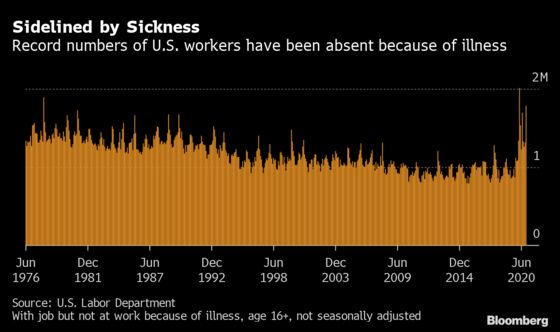

I do. A lot of people heeded the C.D.C. advice to not travel during Thanksgiving and to limit the size of family get-togethers. And I think that will help a great deal. But clearly large numbers of people did not heed that advice. And that’s the reason for the fear of the spike on top of a spike. We saw that, during the Thanksgiving weekend, we had the highest level of hospitalizations at any time in this pandemic, including the darkest days of spring. That’s going to have consequences in the days to come. I’m concerned that we’ll go into the Christmas holiday week with even higher spikes that will make that holiday all that much more challenging. Spike upon spike upon spike is the fear in this six-week-long period.

One of the signal disasters, as you said earlier, in the Trump Administration was communications, both what the President said about the pandemic and how he said it, the language he couched it in and the attitude he took toward it. Since the election, Trump doesn’t even talk about it on a daily basis.

No, he’s, he’s been awol. He had said in his statements: You know, it’s covid, covid, covid; all they want to talk about is covid. But watch, he said, the news will go away the day after the election. Instead, he’s the one who went away the day after the election. He has hardly spoken on what we’re up against, how bad things are, and what is going to be required. It’s interesting, however. In some ways, that is preferable to his coming in and constantly undermining the public-health messaging. So you have seen the C.D.C. and F.D.A. be able to step up. I can only surmise that what he’s clearly been focussed on is figuring out how to hold on to power. The irony is it’s left the field clear.

President-elect Biden is saying very clearly that this should be thought of as a war. We have to be on a war footing and understand how grave this is. Now you’re getting a unified message that’s coming across, and it’s coming from the President-elect on down and from the career scientists. In the face of the rising levels of disease in the country, you now have some Republican governors who had [opposed] a mask mandate now implementing the mask mandate. And they’re not getting contradicted by the President in that process. So, ironically, look, if I have to have President Trump on the airwaves contradicting everybody, or being awol, I’d rather have him be awol.

Thankfully, we can look forward to a vaccine, but that presents enormous logistical challenges. What are the challenges, and how do you view that rolling out?

Well, this is an undertaking on another scale from anything we’ve been doing in the last year. We have deployed north of a hundred and twenty million coronavirus tests in the course of eight months. This is going to be three hundred and thirty million vaccinations, done twice, and hoping to accomplish it in the course of six months or less. This is with vaccines that are new and that haven’t been produced at this volume before. Their clinical data is just undergoing review for approval by the F.D.A. The task is muddied by the fact that we don’t have a clear understanding of what the supply situation is that we have inherited from the Trump Administration. We also don’t know even what the prioritization is.

I’m concerned that what will happen when the new Administration starts is that they will inherit a lot of public confusion, because each state is now coming to its own conclusion about how they’re going to prioritize things. There’s going to be such demand. People are going to clamor for this vaccine. And, if they think that the system is rigged, we will have even more trouble.

After health-care workers and nursing homes, who gets the vaccine next? It’s almost like some terrible philosophical, moral, ethical conundrum that philosophers are faced with all the time. What are your discussions like when it comes to those next levels?

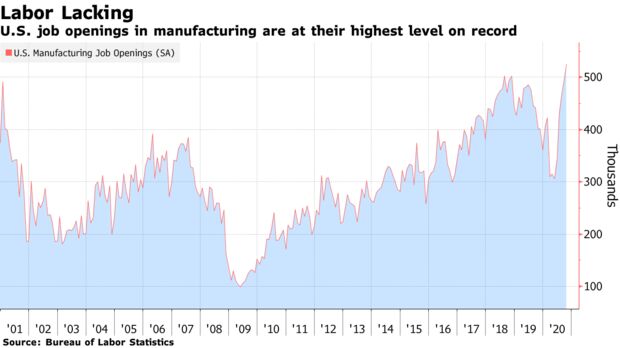

There are eighty-seven million essential workers who are at heightened risk of exposure. They are, say, meatpackers who are exposed to co-workers, or grocery-store workers or bus drivers who are exposed. You’ll be able to go to your local pharmacy and get a vaccine, but what they need to know is, how do they identify who’s the bus driver and who’s not?

Will the government be able to guarantee us that wealthy people, connected people, won’t be able to jump the line?

I think this is one of the critical tests—and an opportunity. The chance to prove that the system is not rigged should not be underestimated. It’s hard. Think about it. The bus drivers never came before the bankers before. You’re going to have Zoom workers who want to go back to normal, and I cannot blame the number of people who will say, You know, thank God I can finally not be in fear. Let me get the vaccine. What do you mean, I have to wait five months? I can imagine a million ways [of jumping the line], people paying someone twenty-five hundred bucks to get your work I.D. tag. This is all about rallying people together. It can’t just be about the rules. It has to be about how we all understand this and work together to say, These are the folks most at risk. They make our subways work. They make our buses work. They get our food supply to us. They make it possible for me to go grocery shopping, and I’ll just have to wait three or four months for my turn.

What you’re talking about is community and common interest and fairness. Many people are very good about that on the level of rhetoric, but, when it comes to their health and their children’s health or their parents’ health, that’s where rubber meets the road.

The mass debate and antagonism we’ve had over the last few months is nothing compared to the splits we will see over “I want my family to be vaccinated.” You know, one person in the family might get vaccinated. Another person might not because they have an illness profile or they have a job that fits in that way. You’ll have children who some families will want to have vaccinated and others will not want to have vaccinated. Pediatric clinical trials have only just gotten under way, and we won’t see those results for a while.

I have a child with severe autism, and so I pay very close attention to the anti-vaxxer movement. And the statistics, the numbers of people who say they will not be vaccinated, is enormous. Doesn’t that have serious implications not only for them but for our over-all effort?

It does. It seems, if we can get around seventy per cent or so of people vaccinated, that would stop the transmission just through vaccination alone. Now if, once people start getting vaccinated, they start throwing their masks away and you can’t get them to do anything else like distancing, then you’re really relying on vaccination as the sole prong of the strategy come three, four months from now. I think there are lots of things that are pushing in the direction of keeping the numbers of people who resist vaccination smaller than those surveys indicate.

What are the numbers?

The numbers suggest that it’s up to as much as forty per cent, even up to fifty per cent, who have said that they are not ready to take the vaccine [even] if the F.D.A. approves it. Part of the reason it’s good that health-care workers would go first is just demonstrating that we ourselves are willing to get vaccinated. Health-care workers are everywhere, which means we’re all going to know people who got vaccinated, and we’re going to see that they did all right.

The reality is that there are memes around anti-vaccination, like: the vaccine will change your D.N.A., or people are injecting a location transmitter into you, a conspiracy to be tagging everybody in the country. We’ll have to be able to combat crazy conspiracy theories. I’ll just summarize by saying this will be contentious, but I’m quite hopeful that we will get to large enough levels of vaccination so that we will be able to get this under control and return to a significant degree of normalcy.

Has there ever been any kind of distribution effort like this in American history?

I draw on things like the polio campaigns, which, you know, took polio from being an annual summer pandemic, in the early fifties, that left kids paralyzed, to essentially being gone a few years after the vaccines came out. Then you had H1N1, where we were in position to vaccinate seventy-million-plus people. So I think there is some precedent. We have not tried to say, Let’s eradicate this disease in one year. Smallpox took a couple of decades. I think we can get [the coronavirus] under control without necessarily eradicating it.

What would it take to eradicate it—or are we never going to eradicate it?

You don’t have to vaccinate every single human being in order to eradicate it. You need to get enough people vaccinated so that the disease stops spreading and dies out. I’m hopeful that we can get it under control here, but, to get eradication, to go back to global travel like before, you would have to get the whole world vaccinated. And that will take years. If we are well vaccinated here, we will feel comfortable over time lifting our restrictions on travel in the United States. And we will become freer to travel to many places around the world. And we will begin to realize what a lot of public-health people like me have been saying, which is that this can’t just be about distribution of vaccine in the United States. This is also going to need to be about enabling global vaccination.

At what point do you think you will be comfortable eating in crowded restaurants, flying on planes, living the life that you lived a year ago?

I think it will be after I get vaccinated [and we have enough data to know the vaccines are stopping transmission]. I’m actually a trial participant. One of the things that’s running through my brain is when I’m going to feel comfortable—when I find out whether I got a placebo or I got the vaccine.

What trial are you in?

I’m in the Moderna trial. After the booster shot, I got a fever, and I had the whole reaction that you would have expected. So I’m going to guess that I got the vaccine. But I won’t feel comfortable that I got it until I actually get that confirmation. But this isn’t about me. I want to see the evidence that the vaccine is lasting. What is the story three months from now? Are the antibodies showing indications that it lasts? I suspect that we’ll really feel comfortable, that we’re able to largely return to normal, maybe in about six months’ time. But, you know, we’re going to go through this gray-zone period where a lot of people have been vaccinated, and I will feel among them. I’m so desperate to go to a concert! Live music is the thing I’ve missed the absolute most.

Dr. Fauci has been a paragon. At the same time, he said, it could be a year and a half for a vaccine to be deployable. Why was the timeline so much faster in the end?

It was insane, some of the timelines that the scientists hit. For example, from the moment that the genome for the virus got sequenced to the moment when the N.I.H.-Moderna team actually was producing the vaccine, it was days. I think it was like a week or something like that. That’s just beyond belief.

What was the science, the discoveries, that made that possible?

Well, it was years of work to build the platform that could deliver the genetic information. Those first few days of success were built on years of work that folks like Dr. Fauci get credit for, because he’s been contributing to the creation of that kind of platform for some years now, as have many biotech companies and many university labs and the government.

Atul, we’re sitting here and watching the year 2020 end—and not a moment too soon. What do you expect will be our situation in December, 2021?

Well, for one thing, I think we’ll be having normal holiday experiences. We’ll be able to get together with our families and spend time. It’s harder for me to predict from my vantage point with as much confidence, but I think that if that’s happening, we will be on better economic terms as well. Right now, airlines, hotels, and any face-to-face service industry—bars, restaurants, child care, health care—I think all of those things are coming back.