Category Archives: Health Insurance Coverage Adequacy

Cartoon – Feeling Better

Tenth year of Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace enrollment begins

https://mailchi.mp/46ca38d3d25e/the-weekly-gist-november-4-2022?e=d1e747d2d8

Tuesday marked the start of the tenth season of open enrollment in the ACA’s health insurance exchanges. Last year, a record 14.5M Americans obtained coverage through the exchanges, and this year’s total is expected to surpass that. That’s thanks to the extended subsidies included in the Inflation Reduction Act, a fix to the “family glitch” that prevented up to 1M low-income families from accessing premium assistance, and expanded offerings by most major insurers, who have been enticed by the exchanges’ recent stability. The average unsubsidized premium for benchmark silver plans in 2023 is expected to rise by about four percent, but the enhanced financial assistance will lower net premiums for most enrollees.

The Gist: ACA marketplace enrollment has grown nearly 80 percent since opening in 2014, and exchange plans now cover 4.5 percent of Americans. After enrollment lagged during the Trump administration, the combination of policy fixes and improved risk pools are attracting insurers back into the exchanges, where enrollees are finding more affordable plans than ever before.

We consider this a commendable first decade, but the success of the exchanges over the next ten years remains subject to political winds. Congress must revisit the extended subsidies by 2025, and a different administration might deprioritize marketplace advertising and navigation support, policies have which proven crucial to the exchanges’ recent growth.

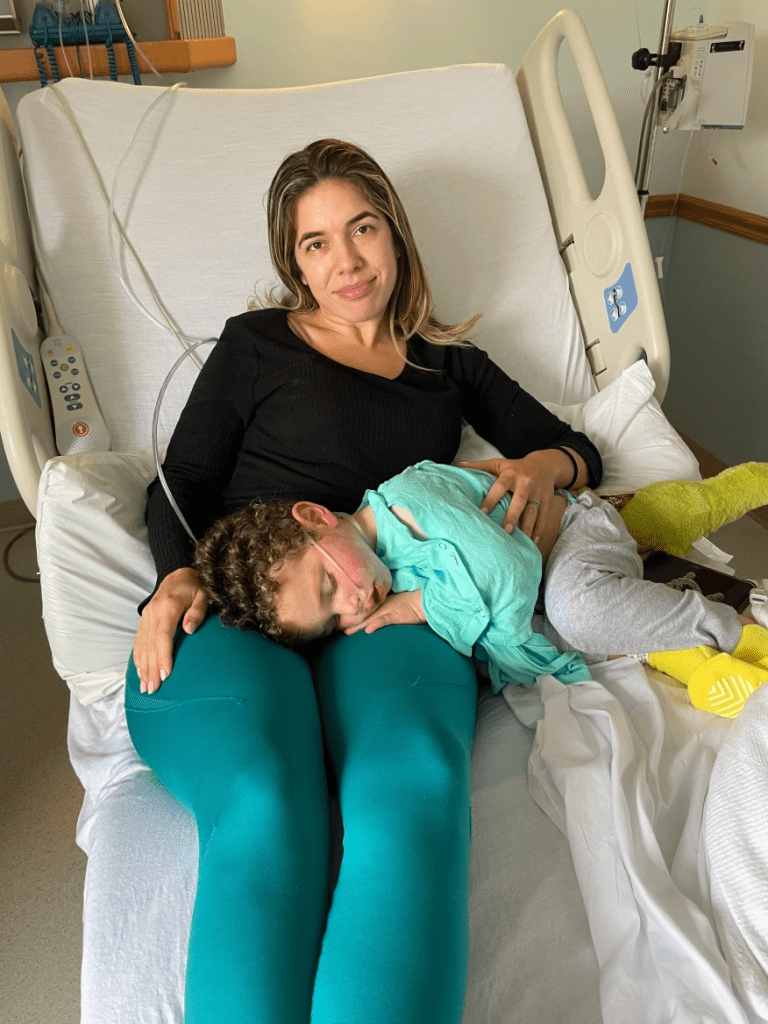

A mother’s harrowing RSV story ends with a simple lesson

I began to wonder if this trip to a pediatric urgent care with my son was even necessary.

Sure, he had been diagnosed with pneumonia a week ago and didn’t seem to be getting better. His cough sounded uglier. But here Ethan was in classic two-and-a-half-year-old mode: running in big circles around the waiting room chairs and causing the kind of ruckus only a toddler can.

He’d stuff some Pirate’s Booty I had hastily thrown into my purse in his mouth, before returning to his wild banshee ways and dashing around in circles again.

Our pediatrician said their office was too swamped with sick kids to see us, and referred us to this place. We had been told the wait to see a doctor would be a minimum of an hour. We struggled to find a seat in the packed waiting room as far as possible from other coughing kids.

We finally graduated from the waiting room to the doctor’s office, only for Ethan to continue his marathon by scooting a rolling chair back and forth, roaring with laughter every time it hit the examining table. When the physician walked in, I felt like I needed to defend wasting her time with this visit with my seemingly A-OK, albeit destructive, son.

But Ethan wasn’t OK.

The doctor listened to his chest with her stethoscope and didn’t like what she heard: wheezing, some crackling.

She showed me how Ethan’s Pirate’s Booty-stuffed stomach moved heavily each time he inhaled and exhaled.

They had Ethan complete a nebulizer treatment in the office, which meant slipping a device on his face that resembled an oxygen mask, while medicated air meant to open up his lungs flowed through a frightfully loud machine. I held him in my lap while the nebulizer was on, scrambling to find 100 different versions of “Wheels on the Bus” videos on YouTube to try to distract him from the vacuum-like whirring of the machine.

The doctor listened to his lungs again. His breathing still didn’t sound great, but she said the hospitals were too inundated right now.

I knew all too well what she meant. A few days before our urgent care visit, I had flagged a report for editors at The Hill that said children’s hospitals in the Washington area were at capacity, flooded with young kids suffering from RSV, a potentially life-threatening respiratory illness that has no vaccine.

After a three-hour visit, she gave Ethan a steroid and told us to follow up with his pediatrician the next day.

By the time we got to the pediatrician’s office the following morning, my happy-go-lucky, playful little guy was anything but. He curled up in my lap, as we went through a similar routine that the urgent care doctor had done just the night before. His oxygen levels were too low, and our pediatrician had him do another nebulizer treatment.

“Our goal is to keep you from going to the hospital,” our pediatrician told us.

It seemed like an unusual “goal” from a doctor, but I understood her reasoning. But after Ethan’s oxygen levels dipped lower still after the nebulizer, she said we should rush him straight to the hospital after all.

My “Blue’s Clues” and vehicle-obsessed son, usually the epitome of toddler “I can do it myself!” independence, wouldn’t let me put him down for even a moment as we waited in the emergency room lobby. Surprisingly, a separate waiting area in the ER just for children wasn’t completely full, and I wondered if maybe news reports of endless waits were overblown.

Not so.

“He’s so cute,” a young mother in the waiting room told me, as she motioned to Ethan’s head of curls. She cradled her two-month-old in her arms, patiently rocking the baby after telling me she had waited three hours so far.

I held Ethan as my husband rushed from work to the hospital, meeting us there and with us as we were brought to an ER triage area. They ran more oxygen tests on Ethan, got some of his history, and then sent us back to the waiting room.

Finally, they called Ethan’s name and we were in the ER. My vibrant, otherwise-healthy kid was lethargic, laying on me with a glazed look in his eyes. We struggled to fit the two of us on an exam table meant for a single adult. They draped a lead apron over me and Ethan as they took X-rays of his tiny lungs. The nurse placed a cannula in Ethan’s nose for supplemental oxygen and put an IV in his arm to give him fluids, before wrapping it with a diaper so he wouldn’t try to take out the tube.

My husband and I, loopy from what was happening, laughed at the sight of a diaper being used MacGyver-style. “Hey, it works!” the nurse said, explaining that he’d done the maneuver with kid after kid in recent weeks.

The ER doctor finally came in our room and delivered a crash course in what might be to come. “Everywhere is full. The entire Eastern seaboard,” he said of hospitals.

“We’ve been airlifting kids to Pittsburgh, sometimes to Richmond,” he added. This hospital had a pediatric unit, but not an intensive care geared towards kids. So if Ethan’s condition became even more dire, they wouldn’t be able to treat him there. Our only hope was that the pediatric unit, which had just a few remaining beds, accepted him.

It was a gut punch. As the doctor left, my husband looked at Ethan, who had fallen asleep with a mask on as the nebulizer loudly buzzed away for another treatment.

“He’s just a baby. He’s not supposed to be here,” my husband said, defeated.

The pediatric unit doctor finally came into our room. She examined Ethan, and briefed us on how they’ve been dealing with case after case of the same thing: RSV.

But she offered us hope: he could head to the pediatric unit at the hospital. We wouldn’t need to travel for his care, as long as he didn’t worsen. Ten hours after we first entered the hospital, we had a bed for Ethan.

We’re among the lucky ones. We were told beyond airlifting, plenty of families had been spending multiple nights in the ER because there were no beds.

In Maryland, Gov. Larry Hogan (R) announced last week that that hospitals would receive $25 million in additional funding from the state to prioritize pediatric intensive care unit staffing. Children from birth to age two comprised 57 percent of hospitalizations last week, according to Hogan’s office.

Next to the ghost decorations for Halloween adorning the doors of the pediatric unit, room after room had the same notice taped up: isolation guidelines. The rooms were all filled with kids facing the exact same thing as Ethan. RSV was everywhere.

There’s no cure for RSV. Every two hours on the dot, the nurses would give Ethan the nebulizer treatment.

A monitor affixed to his foot would alert nurses if his oxygen dipped dangerously low, which it did several times throughout the first night. I thought at one point to ask what happens if Ethan stopped responding to the treatments, but then didn’t ask because I didn’t want to know the answer.

The goal was to get him going without the need for additional oxygen, and breathing well for at least four hours between treatments, two times in a row.

That seemingly simple goal proved elusive for two full days. I originally thought it would be a nightmare trying to get a two-year-old to stay in a hospital bed for more than five minutes, but Ethan was in such bad shape that he barely made a fuss. Then, after midnight on our second night in the hospital, Ethan suddenly perked up.

He sat up and rolled over in the hospital bed. Then, he rolled onto my head, spreading his arms and legs out as far as he could stretch, and giggled.

“Should I sleep here?” he said, cracking himself up.

It was like someone hit the power button on my kid, and suddenly he snapped back to himself. I didn’t care that it was midnight and we needed to get some extremely interrupted sleep before the next nebulizer treatment. My son was back.

A nurse later told me that she enjoyed working with kids because for as quickly as their health can deteriorate, they can just as speedily bounce back.

After that, the doctor advised us to try stretching out his time between treatments. Finally, we were told he was stable enough to go home. I somehow hadn’t shed a tear the entire time we were at the hospital, but when the doctor signed off on us leaving, I bawled.

As nightmarish an experience as it was, I realize how incredibly fortunate my family is.

My husband and I have jobs that allowed us to drop everything when our son needed help, we have health insurance policies, and resources to get through spending days at the hospital.

Perhaps most importantly, we had access to an incredible team of doctors and nurses and the sheer fortune of being able to get a bed for our son during an unprecedented and unthinkable time for hospitals.

At the risk of repeating one of those parenting cliches that I would’ve rolled my eyes at a week ago, I’m thankful that I trusted my gut. Even when Ethan was being a wild child at urgent care, I knew something just wasn’t right. What I didn’t know was how much he had been struggling to breathe.

At the hospital after being discharged, Ethan and I waited in the lobby as my husband went to get our car from the parking lot to pick us up. Ethan spotted some empty wheelchairs in the corner of the lobby, and immediately ran over to them. He giggled as he tried to roll one of the chairs into the automatic opening and closing doors. As I looked on as he laughed and laughed at the pint-sized commotion he created, I breathed a sigh of relief.

The next health care wars are about costs

All signs point to a crushing surge in health care costs for patients and employers next year — and that means health care industry groups are about to brawl over who pays the price.

Why it matters: The surge could build pressure on Congress to stop ignoring the underlying costs that make care increasingly unaffordable for everyday Americans — and make billions for health care companies.

[This special report kicks off a series to introduce our new, Congress-focused Axios Pro: Health Care, coming Nov. 14.]

- This year’s Democratic legislation allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices was a rare case of addressing costs amid intense drug industry lobbying against it. Even so, it was a watered down version of the original proposal.

- But the drug industry isn’t alone in its willingness to fight to maintain the status quo, and that fight frequently pits one industry group against another.

Where it stands: Even insured Americans are struggling to afford their care, the inevitable result of years of cost-shifting by employers and insurers onto patients through higher premiums, deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs.

- But employers are now struggling to attract and retain workers, and forcing their employees to shoulder even more costs seems like a less viable option.

- Tougher economic times make patients more cost-sensitive, putting families in a bind if they get sick.

- Rising medical debt, increased price transparency and questionable debt collection practices have rubbed some of the good-guy sheen off of hospitals and providers.

- All of this is coming to a boiling point. The question isn’t whether, but when.

Yes, but: Don’t underestimate Washington’s ability to have a completely underwhelming response to the problem, or one that just kicks the can down the road — or to just not respond at all.

Between the lines: If you look closely, the usual partisan battle lines are changing.

- The GOP’s criticism of Democrats’ drug pricing law is nothing like the party’s outcry over the Affordable Care Act, and no one seriously thinks the party will make a real attempt to repeal it.

- One of the most meaningful health reforms passed in recent years was a bipartisan ban on surprise billing, which may provide a more modern template for health care policy fights.

- Surprise medical bills divided lawmakers into two teams, but it wasn’t Democrats vs. Republicans; it was those who supported the insurer-backed reform plan vs. the hospital and provider-backed one. This fight continues today — in court.

The bottom line: Someone is going to have to pay for the coming cost surge, whether that’s patients, taxpayers, employers or the health care companies profiting off of the system. Each industry group is fighting like hell to make sure it isn’t them.

Inflation Is Squeezing Hospital Margins—What Happens Next?

https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/inflation-squeezing-hospital-margins-happens-next

Hospitals in the United States are on track for their worst financial year in decades. According to a recent report, median hospital operating margins were cumulatively negative through the first eight months of 2022. For context, in 2020, despite unprecedented losses during the initial months of COVID-19, hospitals still reported median eight-month operating margins of 2 percent—although these were in large part buoyed by federal aid from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act.

The recent, historically poor financial performance is the result of significant pressures on multiple fronts. Labor shortages and supply-chain disruptions have fueled a dramatic rise in expenses, which, due to the annually fixed nature of payment rates, hospitals have thus far been unable to pass through to payers. At the same time, diminished patient volumes—especially in more profitable service lines—have constrained revenues, and declining markets have generated substantial investment losses.

While it’s tempting to view these challenges as transient shocks, a rapid recovery seems unlikely for a number of reasons. Thus, hospitals will be forced to take aggressive cost-cutting measures to stabilize balance sheets. For some, this will include department or service line closures; for others, closing altogether. As these scenarios unfold, ultimately, the costs will be borne by patients, in one form or another.

Hospitals Face A Difficult Road To Financial Recovery

There are several factors that suggest hospital margins will face continued headwinds in the coming years. First, the primary driver of rising hospital expenses is a shortage of labor—in particular, nursing labor—which will likely worsen in the future. Since the start of the pandemic, hospitals have lost a total of 105,000 employees, and nursing vacancies have more than doubled. In response, hospitals have relied on expensive contract nurses and extended overtime hours, resulting in surging wage costs. While this issue was exacerbated by the pandemic, the national nursing shortage is a decades-old problem that—with a substantial portion of the labor force approaching retirement and an insufficient supply of new nurses to replace them—is projected to reach 450,000 by 2025.

Second, while payment rates will eventually adjust to rising costs, this is likely to occur slowly and unevenly. Medicare rates, which are adjusted annually based on an inflation projection, are already set to undershoot hospital costs. Given that Medicare doesn’t issue retrospective corrections, this underadjustment will become baked into Medicare prices for the foreseeable future, widening the gap between costs and payments.

This leaves commercial payers to make up the difference. Commercial rates are typically negotiated in three- to five-year contract cycles, so hospitals on the early side of a new contract may be forced to wait until renegotiation for more substantial pricing adjustments. “Negotiation” is also the operative term here, as payers are under no obligation to offset rising costs. Instead, it is likely that the speed and degree of price adjustments will be dictated by provider market share, leaving smaller hospitals at a further disadvantage. This trend was exemplified during the 2008 financial crisis, in which only the most prestigious hospitals were able to significantly adjust pricing in response to historic investment losses.

Finally, economic uncertainty and the threat of recession will create continued disruptions in patient volumes, particularly with elective procedures. Although health care has historically been referred to as “recession-proof,” the growing prevalence of high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) and more aggressive cost-sharing mechanisms have left patients more exposed to health care costs and more likely to weigh these costs against other household expenditures when budgets get tight. While this consumerist response is not new—research on previous recessions has identified direct correlations between economic strength and surgical volumes—the degree of cost exposure for patients is historically high. Since 2008, enrollment in HDHPs has increased nearly four-fold, now representing 28 percent of all employer-sponsored enrollments. There’s evidence that this exposure is already impacting patient decisions. Recently, one in five adults reported delaying or forgoing treatment in response to general inflation.

Taken together, these factors suggest that the current financial pressures are unlikely to resolve in the short term. As losses mount and cash reserves dwindle, hospitals will ultimately need to cut costs to stem the bleeding—which presents both challenges and opportunities.

Direct And Indirect Consequences For Cost, Quality, And Access To Care

Inevitably, as rising costs become baked into commercial pricing, patients will face dramatic premium hikes. As discussed above, this process is likely to occur slowly over the next few years. In the meantime, the current challenges and the manner in which hospitals respond will have lasting implications on quality and access to care, particularly among the most vulnerable populations.

Likely Effects On Patient Experience And Quality Of Care

Insufficient staffing has already created substantial bottlenecks in outpatient and acute-care facilities, resulting in increased wait times, delayed procedures, and, in extreme cases, hospitals diverting patients altogether. During the Omicron surge, 52 of 62 hospitals in Los Angeles, California, were reportedly diverting patients due to insufficient beds and staffing.

The challenges with nursing labor will have direct consequences for clinical quality. Persistent nursing shortages will force hospitals to increase patient loads and expand overtime hours, measures that have been repeatedly linked to longer hospital stays, more clinical errors, and worse patient outcomes. Additionally, the wave of experienced nurses exiting the workforce will accelerate an already growing divide between average nursing experience and the complexity of care they are asked to provide. This trend, referred to as the “Experience-Complexity Gap,” will only worsen in the coming years as a significant portion of the nursing workforce reaches retirement age. In addition to the clinical quality implications, the exodus of experienced nurses—many of whom serve in crucial nurse educator and mentorship roles—also has feedback effects on the training and supply of new nurses.

Staffing impacts on quality of care are not limited to clinical staff. During the initial months of the pandemic, hospitals laid off or furloughed hundreds of thousands of nonclinical staff, a common target for short-term payroll reductions. While these staff do not directly impact patient care (or billed charges), they can have a significant impact on patient experience and satisfaction. Additionally, downsizing support staff can negatively impact physician productivity and time spent with patients, which can have downstream effects on cost and quality of care.

Disproportionate Impacts On Underserved Communities

Reduced access to care will be felt most acutely in rural regions. A recent report found that more than 30 percent of rural hospitals were at risk of closure within the next six years, placing the affected communities—statistically older, sicker, and poorer than average—at higher risk for adverse health outcomes. When rural hospitals close, local residents are forced to travel more than 20 miles further to access inpatient or emergency care. For patients with life-threatening conditions, this increased travel has been linked to a 5–10 percent increase in risk of mortality.

Rural closures also have downstream effects that further deteriorate patient use and access to care. Rural hospitals often employ the majority of local physicians, many of whom leave the community when these facilities close. Access to complex specialty care and diagnostic testing is also diminished, as many of these services are provided by vendors or provider groups within hospital facilities. Thus, when rural hospitals close, the surrounding communities lose access to the entire care continuum. As a result, individuals within these communities are more likely to forgo treatment, testing, or routine preventive services, further exacerbating existing health disparities.

In areas not affected by hospital closures, access will be more selectively impacted. After the 2008 financial crisis, the most common cost-shifting response from hospitals was to reduce unprofitable service offerings. Historically, these measures have disproportionately impacted minority and low-income patients, as they tend to include services with high Medicaid populations (for example, psychiatric and addiction care) and crucial services such as obstetrics and trauma care, which are already underprovided in these communities. Since 2020, dozens of hospitals, both urban and rural, have closed or suspended maternity care. Similar to closure of rural hospitals, these closures have downstream effects on local access to physicians or other health services.

Potential For Productive Cost Reduction And The Need For A Measured Policy Response

Despite the doom-and-gloom scenario presented above, the focus on hospital costs is not entirely negative. Cost-cutting measures will inevitably yield efficiencies in a notoriously inefficient industry. Additionally, not all facility closures negatively impact care. While rural facility closures can have dire consequences in health emergencies, studies have found that outcomes for non-urgent conditions remained similar or actually improved.

Historically, attempts to rein in health care spending have focused on the demand side (that is, use) or on negotiated prices. These measures ignore the impact of hospital costs, which have historically outpaced inflation and contributed directly to rising prices. Thus, the current situation presents a brief window of opportunity in which hospital incentives are aligned with the broader policy goals of lowering costs. Capitalizing on this opportunity will require a careful balancing act from policy makers.

In response to the current challenges, the American Hospital Association has already appealed to Congress to extend federal aid programs created in the CARES Act. While this would help to mitigate losses in the short term, it would also undermine any positive gains in cost efficiency. Instead of a broad-spectrum bailout, policy makers should consider a more targeted approach that supports crucial community and rural services without continuing to fund broader health system inefficiencies.

The establishment of Rural Emergency Hospitals beginning in 2023 represents one such approach to eliminating excess costs while preventing negative patient consequences. This rule provides financial incentives for struggling critical access and rural hospitals to convert to standalone emergency departments instead of outright closing. If effective, this policy would ensure that affected communities maintain crucial access to emergency care while reducing overall costs attributed to low-volume, financially unviable services.

Policies can also help promote efficiencies by improving coverage for digital and telehealth services—long touted as potential solutions to rural health care deserts—or easing regulations to encourage more effective use of mid-level providers.

Conclusion

The financial challenges facing hospitals are substantial and likely to persist in the coming years. As a result, health systems will be forced to take drastic measures to reduce costs and stabilize profit margins. The existing challenges and the manner in which hospitals respond will have long-term implications for cost, quality, and access to care, especially within historically underserved communities. As with any crisis, though, they also present an opportunity to address industrywide inefficiencies. By relying on targeted, evidence-based policies, policy makers can mitigate the negative consequences and allow for a more efficient and effective system to emerge.

Poll: Voters may cross party lines for lower health care costs

https://www.axios.com/2022/10/20/midterm-election-voters-health-care

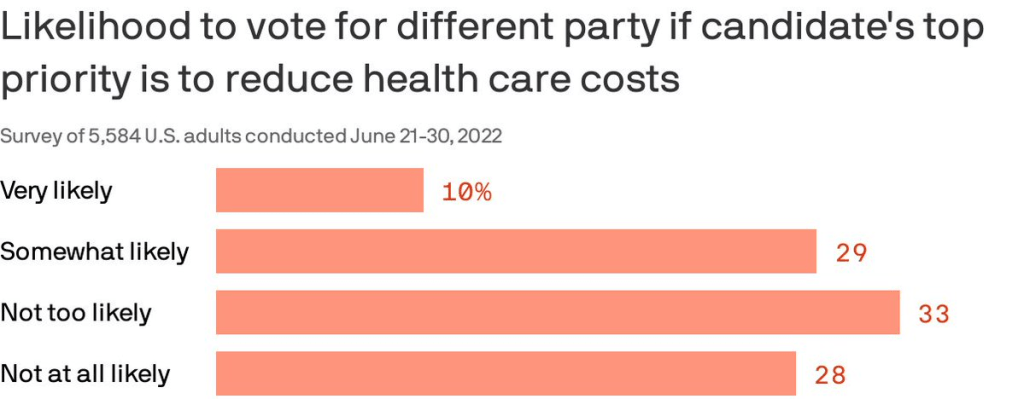

Almost 40% of Americans are willing to split their ticket and vote for a candidate from the opposing party who made a top priority of lowering health costs, according to a Gallup/West Health poll published Thursday.

Why it matters: Though candidates haven’t been talking much about medical costs in the run-up to the midterms, the issue remains enough of a priority that it could erode straight party-line voting.

By the numbers: 87% of Americans polled said a candidate’s plan to reduce the cost of health care services was very or somewhat important in casting a vote.

- The issue cut across partisan lines, with 96% of Democrats and 77% of Republican respondents saying a candidate with a health care costs plan was an important factor.

- 86% also said a plan to lower prescription drug prices is very or somewhat important. That’s especially true for seniors.

Of note: Democratic voters were more likely than Republicans to say they would cross party lines because health costs are a top priority. Four in 10 Democrats said they were likely to do so compared to about 1 in 5 Republicans.