Category Archives: Health Insurance Coverage Adequacy

A Self-Inflicted Wound: The Looming Loss of Coverage

https://www.medpagetoday.com/opinion/second-opinions/101004?trw=no

Millions are about to lose Medicaid while still eligible.

President Biden recently said that the pandemic is “over.” Regardless of how you feel about that statement or his clarification, it is clear that state and federal health policy is and has been moving in the direction of acting as if the pandemic is indeed over. And with that, a big shoe yet to drop looms large — millions of Americans are about to lose their Medicaid coverage, even though many will still be eligible. This amounts to a self-inflicted wound of lost coverage and a potential crisis for access to healthcare, simply because of paperwork.

An August report from HHS estimated that about 15 million Americans will lose either Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) coverage once the federal COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) declaration is allowed to expire. Of these 15 million, 8.2 million are projected to be people who no longer qualify for Medicaid or CHIP — but nearly just as many (6.8 million) will become uninsured despite still being eligible.

Why Is This Happening?

This Medicaid “cliff” will happen because the extra funding states have been receiving under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) since March 2020 was contingent upon keeping everyone enrolled by halting all the bureaucracy that determines whether people are still eligible. Once all the processes to redetermine eligibility resume, the lack of up-to-date contact information, requests for documentation, and other administrative burdens will leave many falling through the cracks. A wrong address, one missed letter, and it all starts to unravel. This will have potentially devastating implications for health.

When Will This Happen?

HHS has said they will provide 60 days’ notice to states before any termination or expiration of the PHE — and they haven’t done so yet. It also seems incredibly unlikely that they would announce an end date for the PHE before the midterm elections, as that would be a major self-inflicted political wound. So, odds are that we are safe until at least January 2023 — but extensions beyond that feel less certain.

What Are States Doing to Prepare?

CMS has issued a slew of guidance over the past year to help states prepare for the end of the PHE and minimize churn, another word for when people lose coverage. Some of this guidance has included ways to work with managed care plans, which deliver benefits to more than 70% of Medicaid enrollees, to obtain up-to-date beneficiary contact information, and methods of conducting outreach and providing support to enrollees during the redetermination process.

However, the end of the PHE and the Medicaid redetermination process will largely be a state-by-state story. Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families has been tracking how states are preparing for the unwinding process. Unsurprisingly, there is considerable variation between states’ plans, outreach efforts, and the types of information accessible to people looking to renew their coverage. For example, less than half of all states have a publicly available plan for how the redetermination process will occur. While CMS has encouraged states to develop plans, they are not required to submit their plans to CMS and there is no public reporting requirement.

Who Will Be Hurt Most?

If you dig into the HHS report, you will see that the disenrollment cliff will likely be a disaster for health equity — as if the inequities of the pandemic itself weren’t enough. A majority of those projected to lose coverage are non-white and/or Latinx, making up 52% of those losing coverage because of changes in eligibility and 61% among those losing coverage because of administrative burdens. Only 17% of white non-Latinx are projected to be disenrolled inappropriately, compared to 40% of Black non-Latinx, 51% of Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander, and 64% of Latinx people — a very grim picture. This represents a disproportionate burden of coverage loss, when still eligible, among those already bearing inequitable burdens of the pandemic and systemic racism more generally.

Another key population at risk are seniors and people with disabilities who have Medicaid coverage, or those who aren’t part of the Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) population. Under the Affordable Care Act, states are required to redetermine eligibility at renewal using available data. This process, known as ex parte renewal, prevents enrollees from having to respond to, and potentially missing, onerous re-enrollment notifications and forms. Despite federal requirements, not all states attempt to conduct ex parte renewals for seniors and people with disabilities who have Medicaid coverage, or those who aren’t qualifying based on income. Excluding these groups from the ex parte process has important health equity implications, leaving already vulnerable groups more exposed and at risk for having their coverage inappropriately terminated.

What Can Be Done?

There are ways to mitigate some of this coverage loss and ensure people have continued access to care. HHS recently released a proposed rule that would simplify the application for Medicaid by shifting more of the burden of the application and renewal processes onto the government as opposed to those trying to enroll or renew their coverage. We could also change the rules to allow states to use more data, like information collected to verify eligibility for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), in making renewal decisions, rather than relying so much on income. The Biden administration also made significant investments into navigator organizations, which can help those who are no longer eligible for Medicaid transition to marketplace coverage. Furthermore, states should use this as an opportunity to determine the most effective ways to reach Medicaid enrollees by partnering with researchers to test different communication methods surrounding renewals and redeterminations.

As the federal government and state Medicaid agencies continue to prepare for the end of the PHE, it is critical that they consider who these burdensome processes will affect the most and how to improve them to prevent people from falling through the cracks. More sick Americans without access to care is the last thing we need.

Court ruling threatens Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) no-cost requirement for preventive care services

https://mailchi.mp/6a3812741768/the-weekly-gist-september-9-2022?e=d1e747d2d8

The same Texas federal judge who ruled the entire ACA unconstitutional in 2018—a decision overturned by the Supreme Court last year—ruled this week that the ACA cannot require a company to fully cover preventive HIV drugs for its employees, on the grounds that doing so violates owners’ religious freedom. He also asserted that the government’s system for deciding what preventive care services should be covered under the ACA is unconstitutional, a broader declaration that potentially jeopardizes a wide swath of no-cost preventive services enshrined in the ACA for millions of Americans, including screening tests for a variety of cancers, sexually transmitted infections, and diabetes. The ruling did not include an injunction and is likely to be appealed.

The Gist: Fully-covered preventive care services are a cornerstone of the ACA, and have increased access to basic healthcare services for many Americans. While there is still some uncertainty about the scope of this ruling, if it were to stand, millions of Americans would once again have to pay for some of the most common and highest-value healthcare services. That additional financial barrier, along with potential tightening of health plan benefit designs, would create barriers to access that only exacerbate our nation’s already stark healthcare disparities.

15 million people may lose Medicaid coverage after COVID-19 PHE ends, says HHS

Children, young adults will be impacted disproportionately, with 5.3 million children and 4.7 million adults ages 18-34 predicted to lose coverage.

Roughly 15 million people could lose Medicaid coverage when the COVID-19 public health emergency ends, and only a small percentage are likely to obtain coverage on the Affordable Care Act exchanges, according to a new report from the Department of Health and Human Services.

Using longitudinal survey data and 2021 enrollment information, HHS estimated that, based on historical patterns of coverage loss, this would translate to about 17.4% of Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) enrollees leaving the program.

About 9.5% of Medicaid enrollees, or 8.2 million people, will leave Medicaid due to loss of eligibility and will need to transition to another source of coverage. Based on historical patterns, 7.9% (6.8 million) will lose Medicaid coverage despite still being eligible – a phenomenon known as “administrative churning” – although HHS said it’s taking steps to reduce this outcome.

Children and young adults will be impacted disproportionately, with 5.3 million children and 4.7 million adults ages 18-34 predicted to lose Medicaid/CHIP coverage. Nearly one-third of those predicted to lose coverage are Hispanic (4.6 million) and 15% (2.2 million) are Black.

Almost one-third (2.7 million) of those predicted to lose eligibility are expected to qualify for marketplace premium tax credits. Among these, more than 60% (1.7 million) are expected to be eligible for zero-premium marketplace plans under the provisions of the American Rescue Plan. Another 5 million would be expected to obtain other coverage, primarily employer-sponsored insurance.

An estimated 383,000 people projected to lose eligibility for Medicaid would fall in the coverage gap in the remaining 12 non-expansion states – with incomes too high for Medicaid, but too low to receive Marketplace tax credits. State adoption of Medicaid expansion in these states is a key tool to mitigate potential coverage loss at the end of the PHE, said HHS.

States are directly responsible for eligibility redeterminations, while the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services provides technical assistance and oversight of compliance with Medicaid regulations. Eligibility and renewal systems, staffing capacity, and investment in end-of-PHE preparedness vary across states.

HHS said it’s working with states to facilitate enrollment in alternative sources of health coverage and minimize administrative churning. These efforts could reduce the number of eligible people losing Medicaid, the agency said.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 extends the ARP’s enhanced and expanded Marketplace premium tax credit provisions until 2025, providing a key source of alternative coverage for those losing Medicaid eligibility, said HHS.

WHAT’S THE IMPACT?

While the model projects that as many as 15 million people could leave Medicaid after the PHE, about 5 million are likely to obtain other coverage outside the marketplace and nearly 3 million would have a subsidized Marketplace option. And some who lose eligibility at the end of the PHE may regain it during the unwinding period, while some who lose coverage despite being eligible may re-enroll.

The findings highlight the importance of administrative and legislative actions to reduce the risk of coverage losses after the continuous enrollment provision ends, said HHS. Successful policy approaches should address the different reasons for coverage loss.

Broadly speaking, one set of strategies is needed to increase the likelihood that those losing Medicaid eligibility acquire other coverage, and a second set of strategies is needed to minimize administrative churning among those still eligible for coverage.

Importantly, some administrative churning is expected under all scenarios, though reducing the typical churning rate by half would result in the retention of 3.4 million additional enrollees.

THE LARGER TREND

CMS has released a roadmap to ending the COVID-19 public health emergency as health officials are expecting the Biden administration to extend the PHE for another 90 days after mid-October.

The end of the PHE, last continued on July 15, is not known, but HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra has promised to give providers 60 days’ notice before announcing the end of the public health emergency.

A public health emergency has existed since January 27, 2020.

Cartoon – Hospital Bedside Today

Cartoon – Credit Blockage

GOP support grows for Medicaid expansion

https://www.axios.com/2022/08/17/medicaid-expansion-republican-states

Republican-led states that have resisted expanding Medicaid for more than a decade are showing new openness to the idea.

Driving the news: In the decade-plus since the landmark Affordable Care Act was enacted, 12 states with GOP-led legislatures still have not expanded Medicaid coverage to people living below 138% of the poverty line (or nearly $19,000 annually for one person in 2022).

- But there’s evidence that the political winds are changing in holdout states like North Carolina, Georgia, Wyoming, Alabama and Texas, as leaders court rural voters, assess new financial incentives and confront the bipartisan popularity of extending health care coverage.

Why it matters: Medicaid expansion, a key component of the Affordable Care Act, means increasing access to federal health insurance coverage for low-income residents, in exchange for a 10% state match of the federal spending.

- Experts say it expands access to care, lowers uninsured rates and improves health outcomes for low-income populations.

- More than 2 million Americans would gain coverage if the 12 states expand Medicaid, according to a 2021 estimate from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The big picture: Some Republican states have already expanded Medicaid through executive authority or — in states where it’s legal to do so — citizen-led ballot initiatives.

- Referendums on the issue passed in Nebraska, Utah and Idaho in 2018 and Missouri and Oklahoma in 2020.

- Medicaid expansion is on this November’s ballot in Republican-controlled South Dakota. (Voters there in June rejected a GOP proposal to make it harder to pass.)

Be smart: In most of the remaining non-expansion states, neither ballot initiatives nor executive authority are options, leaving the legislature with the authority to make the decision.

State of play: In Georgia, as first reported by Axios Atlanta, conversations about a path forward have been taking place behind the scenes in both parties. This follows the stunning support of full expansion legislation by North Carolina’s top Republican this spring, first reported by Axios Raleigh.

- “If there is a person that has spoken out more against Medicaid expansion than I have, I’d like to meet that person,” Republican Senate leader Phil Berger said at a May press conference after reversing his stance. “This is the right thing for us to do.”

- Brian Robinson, former spokesman for the first Georgia governor to reject Medicaid expansion, argued in June it’s time to make the change. Politically, it would “steal an issue” from Democrats, he told Axios Atlanta.

- Policy-wise, “this isn’t what we would do,” Robinson said of Medicaid’s much-criticized structure. “But Republicans can’t agree on what we would do. This is the policy and the law, and it’s not going away. It would bring home hundreds of millions from a program we’re paying into already.”

What they’re saying: “There is real momentum on Medicaid expansion in these conservative states that have been holding out,” said Melissa Burroughs of Families USA, a health care advocacy group working with partners in non-expansion states to push the policy.

- Burroughs told Axios there are Republicans championing or discussing expansion in every non-expansion state, but often “political dynamics and leadership” stand in the way.

Former Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley, who had refused to expand Medicaid himself, is now urging his fellow Republicans to pass it for the benefit of rural parts of the state.

- The bipartisan legislative movement on expansion this year has given advocates in Wyoming hope.

- In Texas, the state with the highest percentage of uninsured residents per capita, some Republicans have co-sponsored Medicaid expansion bills. That indicates “cracks” in Republican opposition, Luis Figueroa, legislative and policy director at progressive think tank Every Texan, told Axios Austin’s Nicole Cobler and Asher Price.

- Tennessee’s Republican lieutenant governor suggested possible openness to the policy last year, though there’s been no meaningful legislative movement.

Details: The winds are shifting for several reasons, experts told Axios.

- Money: The 2021 federal pandemic relief law sweetened the deal for non-expansion states, with a provision designed to offset states’ costs entirely for the first two years. Plus, Republicans’ initial fears that the federal government would pull its 90% matching funds haven’t come to pass.

- COVID-19: Under the federal state of a public health emergency, Medicaid access was automatically extended. But those temporary allowances could lift next year and millions could lose coverage, putting additional pressure on leaders.

- Politics: Medicaid expansion continues to be broadly popular, and the Republican campaign to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act has failed in the courts and Congress — neutralizing what was once a key argument against expansion.

- Health care access: As hospitals across the country close, deepening the rural health care crisis, the benefit of getting more reimbursement from additional Medicaid recipients is difficult to ignore for rural hospital revenues — though the policy is not a silver bullet to end the crisis.

The intrigue: Democrats in these states, including gubernatorial candidates like Georgia’s Stacey Abrams and Texas’ Beto O’Rourke, continue to campaign heavily on Medicaid expansion — banking on polling showing the policy to be consistently popular among the public.

- “I think a lot of Republican members would like to extend Medicaid even more than they will say it,” Texas Democratic State Sen. Nathan Johnson, who has led the push for expansion there, told Axios Austin’s Cobler and Price.

- He said Republicans “are handcuffed by the ideological and political constraints. They will try to do some things to help people, but they need to get over the reflexive opposition to Medicaid expansion.”

Yes, but: Proposals to expand Medicaid did not even get a committee hearing in Texas in 2021 — let alone a vote in either legislative chamber.

Between the lines: Even in non-expansion states, partial expansion proposals have gained traction.

- Kaiser Health News found that nine of the 12 states have sought or plan to seek an extension of postpartum Medicaid coverage, including for up to one year in North Carolina, Tennessee, South Carolina and Georgia.

- Some states, including South Carolina and Georgia, have pushed for partial Medicaid expansion through waivers with work requirements that the Biden administration has rejected. Georgia sued over the rejection, joining a national, ongoing legal fight over the constitutionality of work requirements.

What we’re watching: Even in holdout states showing signs of momentum, the issue remains politically fraught.

- North Carolina’s most powerful politicians say the state’s negotiations this year were torpedoed by hospitals, though Democrats and Republicans alike are optimistic about its chances next session.

- In Georgia, while new conversations are happening, an exact legislative strategy isn’t yet clear, especially given the state’s close November gubernatorial election.

- In Texas, Figueroa said, the governor and lieutenant governor remain the roadblocks because they “aren’t willing to budge.”

House expected to vote to pass healthcare and climate reform bill, sending it to President Biden for signature

https://mailchi.mp/11f2d4aad100/the-weekly-gist-august-12-2022?e=d1e747d2d8

The $740B Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) includes significant reforms for Medicare’s drug benefits, including capping seniors’ out-of-pocket drug spending at $2,000 per year, and insulin at $35 per month. Medicare plans to fund these provisions by requiring rebates from manufacturers who increase drug prices faster than inflation, and through negotiating prices for a limited number of costly drugs. Drug prices are consistently a top issue for voters, but seniors won’t see most of these benefits until 2025 or beyond, well after this year’s midterms and the 2024 general election.

The Gist: While this package allows Democrats to deliver on their campaign promise to allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices, the scope is more limited than previous proposals. Over the next decade, Medicare will only be able to negotiate prices for 20 drugs that lack competitors and have been on the market for several years.

Still, because much Medicare drug spending is concentrated on a few high-cost drugs, the Congressional Budget Office projects the bill will reduce Medicare spending by $100B over ten years. However, these negotiated rates and price caps don’t apply to the broader commercial market, and some experts are concerned this will lead manufacturers to raise prices on those consumers—creating yet another element of the cost-shifting which has been the hallmark of our nation’s healthcare system.

The pharmaceutical industry also claims that this “government price setting” will hamper drug development (although there is limited to no evidence to support this proposition), signaling that they will likely spend the next several years trying to influence the rulemaking process as the new law is implemented.

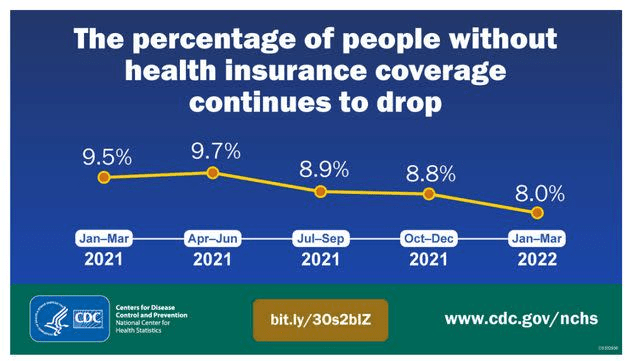

National uninsured rate hit record low this year

The national uninsured rate reached an all-time low of 8 percent in the first quarter of 2022, according to an HHS report released Aug. 2.

The report analyzed data from the National Health Interview Survey and the American Community Survey, according to an Aug. 2 HHS news release.

Three things to know:

1. The previous record low uninsured rate was 9 percent, set in 2016.

2. The uninsured rate among adults ages 18-64 was 11.8 percent in the first quarter of 2022. The uninsured rate for children ages 0-17 was 3.7 percent.

3. About 5.2 million people have gained health coverage since 2020. Gains in coverage are concurrent with the implementation of the American Rescue Plan’s enhanced ACA Marketplace subsidies, the continuous enrollment provision in Medicaid, several state Medicaid expansions and enrollment outreach efforts.

Insurers raise Affordable Care Act (ACA) plan premiums next year

https://mailchi.mp/efa24453feeb/the-weekly-gist-july-22-2022?e=d1e747d2d8

After a few years of relatively unchanged monthly premiums, a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of 72 rate filings for 2023 finds a median 10 percent increase. Insurers say the biggest driver is rising medical costs, driven by higher rates for provider services and pharmaceuticals, as well as a return to pre-pandemic utilization levels. Insurers aren’t expecting COVID-19 or federal policy changes—including a potential extension of enhanced subsidies—to have much of an impact on rates.

The Gist: High inflation and the growing wage-price spiral have left providers with much higher costs, which is sure to drive up the overall cost of healthcare. Where provider systems have the leverage to demand higher rates from insurers, this will inevitably drive up premiums—an effect that is already starting to show up in the individual insurance market.

If Congressional Democrats are able to extend ACA subsidies, most ACA enrollees won’t actually feel these premium increases, but as contracts in the group market come up for renewal, we’d expect inflation in employer-sponsored premiums as well. Given the cost-sharing now built into most benefit plans, individual consumers will likely see healthcare join gas, food, and housing as household costs that are experiencing unsustainable inflationary increases.